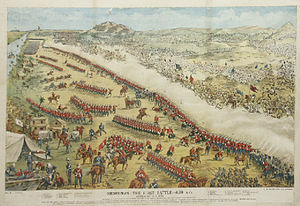

The Battle of Omdurman on September 2, 1898 is the general battle of the Second Anglo-Sudan War between the Anglo-Egyptian expeditionary force of Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener and the forces of the Sudanese rebels (the so-called Mahdists ). Despite the significant inequality of forces - the mahdists had up to 100 thousand fighters against the kitchen of the 25 thousandth Kitchener - the Sudanese suffered a heavy defeat, losing tens of thousands of people. dead and wounded. Despite the high morale of the Sudanese, they could not realize their numerical advantage because of the superiority of the Anglo-Egyptian forces and their overwhelming fire advantage.

| The Battle of Omdurman | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Conflict: Rise of the Mahdists | |||

The Battle of Omdurman, 1898 | |||

| date | September 2, 1898 | ||

| A place | Kerreri Hills, 11 km north of Omdurman , on the banks of the Nile River | ||

| Total | Confident victory of the Anglo-Egyptian troops | ||

| Opponents | |||

| |||

| Commanders | |||

| |||

| Forces of the parties | |||

| |||

| Losses | |||

| |||

During the battle, Kitchener proved himself to be a skillful, energetic, and decisive military leader who, however, showed cruelty and ruthlessness to the vanquished. The battle was marked by a number of new tactics and the use of new weapons - for example, machine guns were used in large numbers for the first time. The use of new types of weapons allowed the British forces to shoot the Mahdist orders at a safe distance, and although the battle sometimes turned into melee (for example, the British forces launched one of the last in the history of large cavalry attacks), it was British firepower that made the main contribution to the victory. As a result of the battle, the Mahdist army ceased to exist as an organized force. Soon, Anglo-Egyptian forces occupied the whole of Sudan, which was legally transformed into an Anglo-Egyptian condominium , but in fact it became a colony within the British Empire.

In the battle of Omdurman , the future British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who commanded one of the squadrons of the 21st Lancers regiment, took part. His memoirs - a great historical work called "War on the River" - are an important source of information about the Sudanese campaign of the British army.

Background

Rise of the Mahdi

- Main article Rise of the Mahdists

In the second half of the 19th century , British influence in Sudan increased markedly. Exploitation of the population by the Egyptian occupation authorities and national oppression led to rebellions that formed into a strong popular protest movement. The religious orientation of this movement was given by its leader Muhammad ibn Abdallah , who in 1881 proclaimed himself the “Mahdi” (messiah) and began to unite the tribes of Western and Central Sudan.

Governor-General of Sudan Rauf Pasha (Egyptian) did not take seriously the information about the Mahdi and sent only two companies of soldiers to suppress the riot. The companies landed on the island where the “Mahdi” was supposedly moving from different directions, stumbled upon each other at night and, deciding that it was the enemy, began to fight among themselves. The detachment of Abdallah, who arrived soon, caught them by surprise and completely defeated them. This success raised the morale of the rebels and increased the number of their supporters.

Rauf Pasha, without making any conclusions, sent 4,000 soldiers under the command of Youssef Pasha to suppress the uprising. But the Egyptian army did not take into account the peculiarities of military operations in the desert, and the army of Muhammad tactically competently evaded the battle, periodically alarming Yousef Pasha with minor attacks. Left without drinking water, government troops were defeated.

The victory over Youssef Pasha caused a general uprising. Now the entire population of Sudan recognized Mohammed "Mahdi", and the power of Egypt was overthrown.

Egypt’s loss of Sudan, as well as some differences with Britain, caused a separate military conflict between them. Egypt set its conditions for the passage of the Suez Canal by British ships, which naturally did not suit the British queen. Pretty quickly, Egypt was occupied and turned into an English protectorate.

Defeat Hick

The new government in Egypt naturally wanted to return the territories lost in the battles with the Mahdi, and raised a corresponding question for Great Britain. The British agreed to provide weapons, but the soldiers were supposed to be Egyptians. By the fall of 1883, the eight-thousandth army of Egypt was created. Her commander was the English general William Hick . Despite his dissatisfaction with his subordinates (they were poorly trained, most did not even know how to read, fighting spirit was absent, since they did not understand the impending war and did not want to fight in the desert), the general was forced to go into battle. So in September of this year, Hick's army advanced on a campaign. The “Mahdi” did not invent anything and, with a tried and tested tactical move, began to exhaust the enemy’s army with partisan raids and long campaigns in the desert. Having made no conclusions about the defeat of the Egyptian army two years earlier, Hick succumbed to this tactical move, and roamed the desert for more than a month after the Sudanese army.

November 3, near the town of El Obeid, the army finally encountered. Abdallah invited Hick's army to surrender voluntarily on gentle terms, but the general decided to fight. The exhausted army of the Egyptians, having lost most of the soldiers during the campaigns, was defeated by the enthusiastic Mahdi soldiers. Sudan completely passed into the power of Muhammad.

Cairo and London did not expect such results. The Egyptian authorities decided to give up new forces, but the British dissuaded them. It was decided to temporarily leave Sudan to itself. The only problem remained was the presence of many Egyptians in Sudan. Britain could not stand aside, so it was necessary to carry out the evacuation, the commander of which was appointed General Charles Gordon .

Gordon's Defeat

On January 8, 1884, the British authorities invited Gordon to lead the operation to evacuate the Egyptians from Khartoum . The general, considering this the only way out of this situation, agreed. His arrival in Khartoum was received with enthusiasm by the Egyptians and with a wave of horror in the Mahdi army from the recollections of his acts in the 1870s . Nevertheless, Gordon, having personally assessed the situation, realized that the mission was doomed to failure and several times requested British support, but Queen Victoria refused. He had only two options: to die with a demoralized poorly trained army or to shamefully escape. As a man of honor, he decided to stay, sat on a camel and alone drove to the Mahdi camp for negotiations. Muhammad Ahmed "Mahdi" rejected the offer of a peaceful withdrawal of the Egyptian army from Khartoum, while not considering Gordon as an enemy, he offered him a choice - to leave untouched or to die with the army.

In March 1884, the Mahdi troops launched a blockade of Khartoum. Charles Gordon managed to hold the city for 317 days. And although Britain finally decided in January 1885 to send troops to help, the Sudanese skillfully forced to delay the advancement of reinforcements. A few days before the assault, the Mahdi again invited Gordon to calmly leave, but the English general did not allow himself to be weak and died heroically during the assault on Khartoum on January 25, 1885 .

The news of the defeat caused widespread discontent in Britain itself. The British made rallies, demanding revenge for the hero-general. Indeed, the campaigns that followed in the late 1890s were carried out under the auspices of revenge for Gordon.

The victory in Khartoum and the death of Gordon made a huge impression on the people of Sudan. The country is conquered, the power of “Mahdi” is unquestioning. Near the conquered Khartoum, "Mahdi" began the construction of a new capital - Omdurman .

The death of the Mahdi and the events of 1885-1895

After the fall of Khartoum in 1885, the British for over 10 years did not take active action against the Mahdist state. However, according to researchers, the rapidly changing political situation forced London to pay closer attention to Sudan.

What was important first of all was that by the mid-90s of the XIX century, Sudan was surrounded by the colonial possessions of European powers, each of which sought to gain a foothold in the Nile Valley. Eritrea and most of Somalia were captured by Italy , the expansion of the German Empire expanded in East Africa, the Belgians developed expansion from the conquered by them Congo . From the west, the possessions of France were approaching Sudan (already during the British invasion of Sudan the colonial contradictions of Paris and London led them to an acute crisis on the brink of war, the so-called Fashodsky incident ). All this posed a direct threat to British colonial interests. The Cabinet of the Prime Minister, Marquis of Salisbury, faced the threat of losing initiative in the colonization of Sudan. In addition, a threat could arise for the British undivided control over the Suez Canal [1] . This pushed London to action. In December 1895, Salisbury announced that the destruction of Mahdism was the task of the British government. Following this, it was decided to occupy Dongola and develop an offensive in Sudan [2] .

The development of an invasion plan was entrusted to the British representative to the Egyptian headive Count Exor . In order to reduce the costs of the British treasury, Salisbury believed that the campaign should be carried out only by the forces of Egypt, which was in fact dependent on England. Formally, the campaign was conducted by Egypt and the invasion forces were considered Egyptian, while, accordingly, the main expenses associated with this campaign fell on the treasury of Egypt (57% of the costs) [3] [4] . Cromer entrusted the overall command of the invading forces to Kitchener, who was appointed commander of the Egyptian army ( serdar ) [5] .

During the period of the existence of the Mahdist state, his army launched several offensive campaigns against neighboring countries under the slogans of jihad , but they did not bring success to the Mahdists. The war with Ethiopia, despite major successes (the Mahdists seized the capital of the country), led to huge human losses; Especially deplorable for Abdallah was the death of almost all the best and most experienced soldiers, including his personal guard. The invasions of the Mahdists into the Italian and Belgian possessions were also reflected [6] .

Sudan by the beginning of the 1890s was experiencing all the growing economic difficulties, not least because of the external blockade. In many areas, the population began to starve. The Caliph was practically deprived of the opportunity to purchase weapons and ammunition. All these factors seriously affected the combat effectiveness of his army [4] .

Invasion of Egypt

Caliph Inspired by His Victory [ which one? ] , decides to attack Egypt. Abdallah orders the governor of the Dongola to launch an attack on Egypt. By that time, the Egyptian units were relatively well equipped and trained under the command of English officers. The conflict ended with the destruction of the invading forces.

In 1890, a terrible mass famine began in Sudan. Severe droughts and the invasion of locusts depleted food sources. Military failure and famine claimed many thousands of lives, which significantly weakened the country.

Party Commanders

Herbert Kitchener ( 1850 - 1916 ), commander of the Anglo-Egyptian forces, was a well-known and honored officer by the mid-1890s. He had extensive experience in various military operations, including even in the Franco-Prussian War (as a volunteer on the side of France) and managed to change several duty stations in the colonies. At the time of the start of the Sudanese campaign, Kitchener had been in Sudan for more than 10 years, holding various posts in the British colonial apparatus and army; for some time he was governor of the port of Suakin . It was believed that Kitchener was a great connoisseur of the country - so, he was fluent in Arabic. Upon being appointed commander in chief, Kitchener was promoted to major general. Having entered command, Kitchener embarked on intensive exercises and took large-scale measures to equip the Egyptian troops with modern equipment [5] .

According to Churchill , Kitchener did not like him from the very beginning of the campaign (he personally knew Winston's father). As Churchill himself wrote much later, in 1923 , about his relationship with him:

| In his youth, he did not like me, he tried to prevent me from participating in the Sudanese campaign and tore up metal, learning that I had ended up in Sudan. A rare case is to dislike for the eyes ... [7] |

All the armed forces of the Mahdists were under the supreme command of the ruler of Sudan Abdallah (Muhammad Abdallah ibn Said, 1846 - 1899 ), known under the honorary nickname Caliph, or the Caliph, descended from the title of Caliph (that is, a ruler combining both absolute secular and spiritual power). Abdallah was one of the main followers and associates of the leader of the Sudanese rebellion, Mahdi . He became ruler after the death of Mahdi in 1885, after which he was able to significantly strengthen the foundations of the Mahdist statehood, in particular, to suppress the separatism of tribal leaders. Abdallah significantly increased and strengthened the army [8] .

Almost the entire history of the Mahdist Sudan, with the exception of a few months, coincides with the period of the reign of Abdallah. Under Abdallah, certain social and economic progress was achieved — trade and crafts, road and school construction developed; uniform legislation was introduced throughout the country. However, in general, Sudan remained an extremely poor and backward country, the majority of whose population existed at the tribal or slave-owning formation stage, and the economy was based on extensive agriculture, the slave trade, and production from military raids. Abdallah also failed to fully cope with the contradictions within the slave-feudal elite of the state, which significantly weakened his strength [9] .

Preparing for the battle

English Training

England followed the development of the situation in Sudan, keeping in mind the thought of the death of Gordon and the alleged revenge. The patience and competent policy of the British soon gave the necessary result. In Egypt, a powerful, well-armed army was formed, consisting of English and Egyptian soldiers, and most importantly, prepared for a desert war. Sudan, on the contrary, fell into a crisis, the army was poorly staffed, and the financial situation could not please either. Everything was in favor of the British.

The Anglo-Egyptian army consisted of about 25,000 soldiers, of which 8,000 were British. The army was armed with new Lee Metford magazine rifles with a rate of about 8-10 rounds per minute, which used a new generation of .303 British rifle cartridges. But the main trump card of the British was Maxim Machine Gun - the only weapon of "mass destruction" of that time. Its rate of fire reached 600 rounds per minute.

On the side of the Sudanese were mainly swords, shields and spears. Part of the Sudanese army was equipped with several thousand captured rifles captured from the Egyptians.

The invasion of Sudan began on March 18, 1896 . The commander in chief of the Anglo-Egyptian army, General Horace Herbert Kitchener, owned information about the area chosen for military operations. While still a major, Kitchener took part in a campaign that never reached Khartoum to save Gordon. Gordon was an idol for him, so Kitchener himself wanted to avenge his death. The general carefully analyzed all the failures of past military operations, identified the reasons to try to avoid them. The sun, lack of water, sandstorms, illnesses destroyed many previous armies. Therefore, Kitchener put emphasis on the good supply of his army with everything necessary and the provision of rear communications.

Anglo-Egyptian troops penetrated Sudan leisurely. Soon they occupied the town of Akasha and set up a military camp there. The Nile River was used as the main transport artery, it was through it that most of everything necessary was delivered. Vessels transporting resources were well protected and possessed guns. was the first serious battle with the Mahdists. Soon, the British faced a problem - Neil has rapids through which it is difficult to cross. Then Kitchener, in order to get around the section of the river with rapids, decided to build a railway. The British government supported this idea, as Britain did not intend to leave Sudan after the war. Under the leadership of Canadian Percy Girard, Egyptian soldiers and convicts began laying the rail. England also laid telephone and telegraph lines.

The constructed railway line gave a great advantage when attacking the Dongola in September 1896 . Ships delivered by rail were launched again. The new river flotilla was used to transport troops and resources, as well as for fire support of troops advancing by land. The battle was short-lived. The rifles and guns of the modern British army left the Sudanese no chance. The city was taken.

After the capture of the Dongola, the engineers proposed to Kitchener a plan for the construction of a railway to Abu Hamid. The construction of a 230-mile road directly across the desert was perceived by many as impossible, but Percy Jaber convinced them otherwise. Having agreed estimates with London, the general gave the go-ahead. The advantage of this road was that it allowed to significantly reduce the travel time to Khartoum and made it possible to bypass three uncomfortable rapids of the Nile. Winston Churchill , then a war correspondent, spoke of the rapids as "a massive staircase of four huge granite steps." As a result, in January 1897, construction began.

Workers were provided with everything necessary: from water and food to army defense from the enemy. The British “flying” units repulsed all attempts of the rebels to hinder the workers without much difficulty. Thanks to telegraph and telephone lines, the British could quickly transfer military aid to battle areas. The ruler of the Sudan understood that the matter was going to defeat, but he could not stop it.

Kitchener decided to build a road further from Abu Hamid south along the Nile up to Atbar, since the Nile’s waters in these areas are also inconvenient for water crossings. And Atbar provided direct access to Khartoum and Omdurman.

In early July 1897 the road was built. Now the British had the opportunity to quickly transfer troops and heavy weapons to any part of the country, supplying them with everything necessary.

Sudan Training

The news of the invasion of Anglo-Egyptian forces on the territory of the country, as well as the fall of the Dongola, caused violent unrest in Omdurman. Khalifa turned to his subjects for understanding, inspired them that there was a Holy War - Jihad , in which Allah would help Muslims, and the blood of infidels would replenish the water of the great Nile. The leader “played” with the people, he convinced them that he saw the spirit of the Mahdi in a dream, which predicted him victory in the upcoming war. He explained the loss of the Dongola by his direct order, in order to prepare a large army for a decisive battle.

Khalifa struggled to strengthen the defense of his capital. He gathered all the troops together on the outskirts of Omdurman. Khalifa considered superiority in quantity and the ability to mobilize even more people as his plus. The fighting spirit of the people was strong, and they believed in victory. Khalifa simply had no other choice: because of the railway, his tactics of maneuvering war in the desert became useless.

In Omdurman, fortifications were urgently built. The capital was guarded by an army of about 60 thousand people. Most of the soldiers were armed only with knives, only a part with rifles. Several cannons were mounted on the forts surrounding the Omdurman. Khalifa’s tactical plan in this situation was simple - he decided to mine the Nile. The primitiveness of the mines was their huge minus: it was just a hermetically sealed boiler with gunpowder, inside which was a gun; a wire was attached to the trigger of the gun, which was pulled across the river; as a result of the boat touching the wire or pulling it with a Sudanese fighter, a shot and detonation of gunpowder occurred. That is all Sudan was able to do in response.

Long inaction had a very negative effect on the discipline of Sudanese militias and, accordingly, on their fighting spirit. The supply system for the army in the Sudan was traditionally absent - it was believed that the soldiers themselves had to take care of food, seizing supplies from the enemy. Since there was no military production this time, the Caliph’s troops began to loot, which led not only to their moral decay, but also to a serious aggravation of relations with the local population. Abdallah was even forced to resort to a kind of “surplus appraisal” - the seizure of grain from the population of some regions of Sudan for the needs of the army. In the already difficult situation with food in the country, this greatly undermined the caliph's authority [4] .

Battle Progress

The British were in no hurry to go on the offensive. They had no cause for concern: their army consisted of about 25 thousand well-trained and equipped soldiers, including 8,200 British soldiers, 17,600 Egyptian soldiers, as well as Arab soldiers of different tribes who joined the campaign for the sake of revenge or revenge on the Mahdists. And the freedom of decisions that General Kitchener gave his subordinates allowed officers to independently solve many problems. The general encouraged the initiative of the junior officers, setting them only general tasks.

The British were armed with 44 fast-firing artillery guns and 20 Maxim machine guns from the infantry, another 36 cannons and 24 Maxim gunboats on gunboats stationed in the Nile. Mining the Nile did not bring results - the British shot mines from machine guns from a long distance. The army was slowly moving toward the goal, and on September 1, 1898, the general and his subordinates saw the walls of the capital.

At dawn on September 2, 1898, the armies entered combat order. Khalifa was determined. He planned to conduct a massive frontal attack and engage in hand-to-hand combat. Indeed, in hand-to-hand combat the British were not so strong. Khalifa was well aware that as long as the troops reached the enemy’s army, many would die in a stream of enemy bullets, but, believing in holy jihad, the soldiers thus reserved their place in paradise. All night before the battle in the camp of Abdallah, the mullahs sang, calling for courage and promising a great victory. The idea of the British was also simple. It came down to the simple conduct of massive fire on the attacking enemy in order to destroy him at a long distance, preventing the Sudanese from engaging in close combat.

According to Winston Churchill , the military order of the Khalifa army was as follows: on the left flank there are about 5,000 soldiers of the Deheim and Kenan tribes led by Ali Wad-Helu, between them and the center there are regular units (12,000 riflemen and 13,000 spearmen) under the command of Osman Sheikh ed Dean and Osman Azraq, in the center - 13,000 spearmen, commanded by Yakub, to the right of the center - about 6,000 dangal under the leadership of the Sheriff. The edge of the right flank, closer to Omdurman, was covered by 1,700 soldiers of the Hadendoa Osman Digna. Abdallah himself, with a bodyguard detachment, was slightly behind the center of the army.

Mahdist First Attack

By 06:40, Kitchener's troops heard a noise made by the advancing army of Abdullah. A few minutes later, Mahdist forces appeared from behind the hills and became clearly visible to the British. Numerically superior forces of the Sudanese began in the mind of the British to line up in a semicircle, covering the enemy. According to eyewitnesses, the dense masses of Sudanese infantry, over which many colorful flags flattered with religious sayings fluttered, were an extremely impressive sight. The Caliph’s troops were moving in regular, orderly lines, rather than in a random crowd, as many British officers expected to see. Particularly even order was kept by selected units located on the right wing of the caliph's army, distinguished by white banners. The Mahdists were obviously inspired by the parting words of clergymen and determined to give their lives for faith - their regiments constantly chanted the Muslim formula of faith - “there is no God but Allah and Muhammad is His prophet” so loudly that it was clearly heard by the English, who were almost in three kilometers [10] .

The Mahdists started the battle first - their guns fired two shots, but the shells fell, not reaching about 50 meters to the Anglo-Egyptian order. After that, at 06:45 from the British side, the 32nd battery opened fire from a distance of 2,800 yards (about 2,560 m), then other batteries were connected to it [11] . The firepower of modern artillery immediately began to affect - the English officers said that the shells, falling into the ranks of the Mahdists, cut them like a plow. Accuracy of fire was greatly facilitated by the fact that the terrain was divided by the British into pre-targeted sectors [10] .

Churchill, who was in the cavalry patrol a little closer to the enemy than the main army, clearly saw how devastated the British shells were in the ranks of the attackers. However, the mahdists continued to move forward:

| At the first minute, at least twenty shells crashed into their ranks. Some burst high in the air, others right in front of them. Some of them stuck deep into the sand and burst, raising clouds of red dust, sweeping away the ranks with fragments and shrapnel. White banners began to fall everywhere. But then they rose when new people went forward to die for the sacred work of the Mahdi ... Under the fire of our artillery, a dense mass of “white banners” crumbled into thin lines of spearmen and shooters who continued to advance ... [12] |

The action of machine-gun fire on the dense orders of the advancing Sudanese was, according to eyewitnesses, monstrous. Churchill wrote that literally piles of defeated bodies grew before the positions of machine gunners. However, one of the serious shortcomings of the Maxim machine gun was immediately revealed - the unreliability of water cooling of the barrel. Intense shooting led to the fact that the water in the cooling covers of the machine guns quickly heated up, boiled and evaporated, which forced to cease fire at the decisive moment of the battle. In such cases, British and Egyptian soldiers rushed to the Nile and brought fresh water [13] .

In the course of the attack, the military order of the Khalifa troops changed somewhat. While the Sheriff and Osman Azraq, with about 15,000 soldiers, mostly from the army of Osman Sheikh al-Din, attacked the British “in the forehead,” Khalifa with about the same number of soldiers stood behind Surgem Hill, which towered before the position of the British. According to Churchill, “if the attack of Azraq were successful, he (Khalifa) would come forward with his guard, the color of the Arab army, and complete the rout of the enemy. If she failed, he would have one more chance. ” While the “white banners” under the bullets and shrapnel burst towards the zerib, Ali Wad-Helu “had to move to the Kerreri hills (on which the right, northern, the flank of the British - A. leaned) and remain among them at a distance of a shot, trying not to attract to attention to yourself. ” In the event that the British, having repelled a head-on attack, left their fortified camp and moved to Omdurman, they would have to be simultaneously attacked by the Khalifa warriors - from Surgam hill, and by Ali Wad-Helu troops and the remnants of the Osman Sheikh al-Din army - from Kerreri, from the north, is surrounded and destroyed. But Khalifa, according to Churchill, did not coordinate the attacks of parts of his army and underestimated the enemy’s firepower.

The hills of Kerreri were held by Egyptian cavalry and dromateria (camel corps) under the general command of Lieutenant Colonel Broadwood . They could not stop the warriors advancing on the hills of Osman Sheikh al-Din and began to retreat east to the Nile. It turned out that camels in hilly areas covered with boulders move slower than foot people, and the dervishes had a chance to cut off the camel corps from the main British forces, to press them to the river and destroy them. The Mahdists energetically rushed to intercept, while clearly winning the pace of progress. Broadwood cavalrymen (nine squadrons) prepared for a suicide counterattack to save the camel corps. But then two English gunboats came ashore one after another and opened dagger fire at the advancing dervis from quick-firing cannons, Maxim machine guns and rifles. “The distance was short, the effect was amazing,” Churchill writes. The attack of the mahdists was choked, the survivors hesitated, the camel corps slipped through a dangerous place and was saved. Enraged by the failure, the Mahdists turned around and rushed to the Broadwood cavalry, and chased after it for three miles to the north. The cavalry “flirted with its mighty adversary like a banderillero who teases a bull. Lieutenant Colonel Broadwood managed to lure this division of the Dervish army far from the battlefield, where it was so much needed, ”- so, according to Churchill, this critical episode of the battle ended.

At this time, to the south, the remnants of the “white banners” joined the center, “and all these 14,000 moved against the zerib, gradually diverging, moving to a more dispersed formation and slowing down. Approximately 800 yards from the British division, the attack stopped - here they could not advance further. In one place, the attacking Sudanese, armed only with Martini-Henry rifles , came up to a distance of 300 yards. One brave man who carried a white banner fell 150 steps from the trench. But the attack was upset ... The surviving dervishes lay down. They could not move forward, but they did not want to retreat either. Their arrows, taking advantage of natural shelters, entered into an unequal duel. By eight o’clock it became clear that the whole attack had failed, ”Churchill writes. Osman Azraq, who personally led the soldiers forward, was killed in this attack.

Kitchener, repelling this furious attack, decided that it was time to leave the camp and take the initiative into his own hands. The hills of Surgem and Kerreri hid from him a significant (about 35,000 people) part of Khalifa's army.

On the left flank of the British, the 21st Lancers regiment advanced, which was tasked with covering the right flank of the enemy and cutting off his retreat to Omdurman. Seeing in front of them thousands of wounded and deserters hurrying to the city and covered only by a chain of shooters, the lancers rushed to the attack. Here they unexpectedly found themselves in front of a dry riverbed, in which a reinforced detachment was hiding under the banner of (about 2700 people). Suddenly for the British, the detachment stepped out of hiding and blocked the path of the ulans. The 21st regiment (about 400 people) got into the ranks of the mahdists. “Two living walls collided,” Churchill writes. The Digny warriors fought bravely and skillfully, using all the techniques they knew to fight the mounted enemy. In two minutes, while the ulans cut through the crowd of enemies, they lost 70 people and 119 horses killed and wounded. The Mahdists quickly closed the ranks, and the Lancers did not dare to make their way back in the same way. Instead, they went to the Makhdists on the flank, dismounted and fired quickly from carbines. The Arabs tried to counterattack, but soon abandoned this venture and in perfect order retreated to the main forces at Surham.

The main forces of Kitchener (the brigades of Maxwell , MacDonald , Lewis, Woopope , Collinson) advanced forward to Surgem Hill. At the same time, the right flank of the British went farther towards the desert. The army and the river formed a semblance of the letter V, turned to the north. At that time, the forces advancing forward were attacked by the Khalifa reserve - the Yakub warriors, who were about 15,000. Seeing their energetic onslaught, Kitchener quickly rebuilt his troops - the army turned front to west, so that its left flank was in the desert, and the right one rested in the river - according to Churchill, "as if she had made a complete somersault over her head." Machine guns played a large role in repelling the fierce onslaught of the Yakub warriors. Lead mowed the dense ranks of dervishes, whose front began to fall apart under the onslaught of the British and Egyptians. The surviving Yakub warriors began to retreat in disorder to Omdurman, but he himself remained at the black banner of Khalifa and died along with his chosen fighters.

At this time, a crisis was outlined on the right flank of the Anglo-Egyptian army, which was attacked by Ali Wad Helu warriors from the north, from the Kerreri hills. While Kitchener was transferring the Lincolnshire regiment to the threatened direction, the brigade of Sudanese riflemen under the command of MacDonald fought off on their own. The brave but impulsive Sudanese very quickly shot down the ammunition stocks, and at some point it seemed that a lively wave of mahdists would reach their order. But the Lincolnshire arrived in time. Under their volleys, the infantry attack of Ali Wad-Helu completely drowned, as did the brave but disorganized attack of several hundred horse-drawn mahdists that followed.

After repulsing the attack from Kerreri, the Anglo-Egyptian army turned to the west with an almost two-mile front and slowly moved forward, driving the mahdists into the desert with fire and bayonets. Broken pursued by lancers and Egyptian horsemen.

By half-past eleven, the Khalifa army remained only in the pages of history.

Summary and Consequences

Losses

The losses of the winners were small compared with the huge losses of the mahdists. On September 2, 387 people were knocked out of the Kitchener’s army, but that number increased several days after the battle, as many of the wounded died. It is estimated that a few days after the battle, the Egyptian and Sudanese units lost 30 people. killed and 279 wounded; White troops lost 28 killed and 115 wounded - a total of 452 people. The main part of the actual British losses fell on the 21st Lancer Regiment - 24 killed. Cameron and Seafort regiments each lost 2 more dead [14] .

The Caliph’s army suffered huge losses. They were calculated only approximately, but most sources agree that from more than 50 thousand who participated in the battle, from 9 to 11 thousand were killed. The number of wounded mahdists is also difficult to estimate, but it was apparently large and absolute, and relative to the number of Sudanese participating in the battle. So, according to the official battle report sent by Kitchener to London, out of more than 4 thousand captured Makhdists, 1,222 were injured. In this case, the report said:

| ... the wounded were in almost every Omdurman house and, given the fact that almost every battle-worthy man in the city was forced to take part in the battle, it would be fair to believe that the number of wounded reported in the telegram (16,000) is not an exaggeration. |

[ten]

Post-battle events

After the battle, naval artillery transferred fire to the capital. In the city, another thousand people died. As a result, the capital fell without resistance. By order of Kitchener, under the slogan "revenge for Gordon", the Mahdi mausoleum was destroyed. His remains were recovered and burned in the furnace of the ship.

Abdallah managed to survive and escape. Soon he tried to organize a guerrilla war in the western regions of Sudan, but his detachment was skillfully defeated by the British. In this fight, Khalifa himself died. All areas of the country gradually laid down their arms. The state of Sudan was destroyed.

In early 1899, an agreement was signed between England and Egypt on the establishment of joint management in the Sudan ( condominium ). But since the British did not reckon with the Egyptians, in fact, Sudan became an English colony.

See also

- XIX century in the history of Sudan

- Halaib's Triangle

- Four Feathers is a novel dedicated to the events that preceded the battle for Omdurman, and two of its adaptations .

Notes

- ↑ David Shonfeld. Battle of Omdurman: September 2nd, 1898 Questia. Trusted Online Research. - History Today, Vol. 48, September 1998. Date of treatment April 3, 2012. Archived on May 29, 2013.

- ↑ World History. Ed. A. A. Guber. . - M .: Publishing house of socio-economic literature, 1960. - T. VII. - S. 225—227. - 820 s. - 164,000 copies.

- ↑ Abbas Mekki. The Sudan Question. The Dispute Over the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1884-1951. - L .: Faber & Faber Ltd, 1951. - S. 45. - 201 p.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Smirnov S.R. History of Sudan (1821-1956). - M .: Nauka , 1968 .-- S. 148-172. - 296 p. - 2 600 copies.

- ↑ 1 2 Kennedy Hickman. Omdurman 1898: Kitchener's Victory in Sudan . Trivia-Library.com. Date of treatment April 4, 2012. Archived May 29, 2013.

- ↑ Muhammad Ahmed ibn Abdullah . Encyclopedia "Around the World." Date of treatment April 4, 2012. Archived May 29, 2013.

- ↑ Churchill W. Sayings and Thoughts. - M .: KoLibri, ABC-Atticus , 2012 .-- S. 144. - 288 p. - ISBN 978-5-389-02627-8 .

- ↑ Abdullah ibn al-Saeed Muhammad Khalifa . Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Date of treatment April 4, 2012. Archived May 29, 2013.

- ↑ Mahdist uprising . Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Date of treatment April 4, 2012. Archived May 29, 2013.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Harold FB Wheeler. The Story of Lord Kitchener. - L .: George G. Harrap & Co, 1916. - S. 116-129.

- ↑ Donald Featherstone. Mahdist War: Battle of Omdurman (English) . Osprey Publishing. Date of treatment April 4, 2012.

- ↑ Winston S. Churchill. India, Sudan. South Africa. Campaigns of the British Army 1897-1900. - M .: Eksmo , 2004 .-- S. 273-300. - 560 s. - ISBN 5-699-06611-X .

- ↑ David Wallechinsky, Irving Wallace. Military and War Weapons the Machine Gun . Trivia-Library.com. - Reproduced with permission from "The People's Almanac" series of books. Date of treatment April 4, 2012. Archived May 29, 2013.

- ↑ GW Steevens. With Kitchener to Khartoum . Internet Archive (2010). Date of treatment May 11, 2012. Archived on May 29, 2013.

Links

Literature

- V. E. Markevich “Handguns”

- Zalessky K. A. Who was who in the Second World War. Allies of Germany. Moscow, 2003