History (from icon and writing ) - iconography, icon writing, a type of medieval painting, religious in themes and subjects, cult by purpose. In the most general sense, the creation of sacred images, intended to be an intermediary between the Divine and earthly worlds during individual prayer or during Christian worship, is one of the manifestations of Divine truth.

Iconography History

The image appeared in Christian art initially. The creation of the first icons is attributed to apostolic times and is associated with the name of the evangelist Luke .

From the 2nd to the 4th centuries, Roman catacombs preserve works of Christian art — wall paintings of a symbolic or narrative character, in which the earliest examples of Christian iconography can be seen.

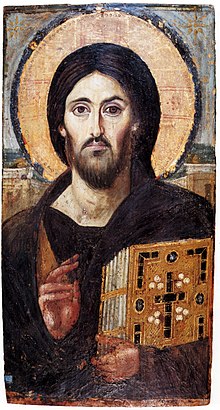

The oldest of the icons that have come down to us belong to the 6th century and are made in the encaustic technique on a wooden base , which makes them related to Egyptian-Hellenistic art (the so-called “ Fayum portraits ”).

The Trull (or Fifth-Sixth) Council prohibits symbolic images of the Savior, prescribing that He be portrayed only " in human nature ."

In the 8th century, the Christian Church was confronted with the heresy of iconoclasm , whose ideology prevailed completely in the state, church and cultural life. Icons continued to be created in the provinces, far from the imperial and church oversight. The development of an adequate response to the iconoclasts, the adoption of the dogma of iconography at the Seventh Ecumenical Council ( 787 ) brought a deeper understanding of the icon, summing up serious theological foundations, linking the theology of the image with Christological dogmas.

The theology of the icon had a great influence on the development of iconography , the folding of iconic canons . Departing from the naturalistic transmission of the sensual world, iconography becomes more conditional, flattened to the surface, the image of faces is replaced by the image of faces, which reflect physical and spiritual, sensual and supersensible. Hellenistic traditions are gradually being reworked and adapted to Christian concepts.

A different understanding of the icon in the Western and Eastern tradition ultimately led to different directions in the development of art in general: having a great influence on the art of Western Europe (especially Italy), iconography during the Renaissance was superseded by painting and sculpture . Iconography developed mainly in the territory of the Byzantine Empire and the countries that adopted the eastern branch of Christianity - Orthodoxy .

The iconography of the main images, as well as the techniques and methods of icon painting, were formed by the end of the iconoclastic times. In the Byzantine era, several periods distinguished by the style of images were distinguished: the Macedonian Renaissance of the 10th - first half of the 11th century, the iconography of the Komninsky period of 1059–1204, the “ Paleologovsky Renaissance ” of the early 14th century.

Iconography together with Christianity comes first to Bulgaria, then to Serbia and Russia. The first known Russian icon painter - St. Alipy (Alimpiy) ( Kiev ,? - 1114 ). The earliest Russian icons were preserved not in the most ancient temples of the south, which were devastated during the Tatar invasions, but in Hagia Sophia in Novgorod the Great . In ancient Russia, the role of the icon in the church has increased unusually (compared with the traditional for Byzantium mosaics and frescoes). It is on Russian soil that the multi-tiered iconostasis is gradually taking shape. The iconography of Ancient Russia is notable for the expressiveness of the silhouette and the clarity of combinations of large color planes, more openness to the upcoming in front of the icon.

Russian iconography reached its highest peak by the 14th — 15th centuries; the outstanding masters of this period are Theophanes the Greek , Andrei Rublev , and Dionysius .

Original schools of icon painting are formed in Georgia and South Slavic countries.

From the 17th century, the decline of icon painting began in Russia, icons began to be written more “to order”, and from the 18th century, traditional tempera ( tempera ) technology was gradually replaced by oil painting , which uses techniques of Western European art school: light and shadow modeling of figures, direct (“scientific” a) perspective , real proportions of the human body, and so on. Icon as close as possible to the portrait . Secular, including non-believers, artists are involved in icon painting.

After the so-called “ opening of the icon ” at the beginning of the 20th century, there was a great interest in ancient icon painting, the technology and attitude of which remained by that time almost exclusively in the Old Believers . The era of the scientific study of the icon begins, mainly as a cultural phenomenon, in full separation from its main function.

After the October Revolution of 1917 , during the period of persecution of the Church, many works of church art were lost, the icon in “the country of victorious atheism” identified the only place - the museum , where it represented “ Old Russian art ”. Iconography had to be restored bit by bit. MN Sokolova (nun Juliana) played a huge role in the revival of icon painting. In the emigrant environment, the Icon community in Paris was restoring the traditions of Russian icon painting.

Schools and styles

For many centuries, the history of icon painting has formed many national icon painting schools that have undergone their own path of stylistic development.

Byzantium

The iconography of the Byzantine Empire was the largest artistic phenomenon in the Eastern Christian world. The Byzantine art culture not only became the ancestor of some national cultures (for example, Old Russian), but also throughout its existence influenced the iconography of other Orthodox countries: Serbia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Russia, Georgia, Syria, Palestine, Egypt. Also influenced by Byzantium was the culture of Italy, especially Venice. The most important for these countries were the Byzantine iconography and the emerging new stylistic movements in Byzantium.

Pre-iconic era

The oldest icons that have reached our time date back to the 6th century. The early icons of the 6th — 7th centuries preserve the ancient painting technique - encaustic . Some works retain some of the features of ancient naturalism and pictorial illusionism (for example, the icons “ Christ Pantocrator ” and “ Apostle Peter ” from the Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai ), while others are prone to conventionality, sketchy images (for example, the icon “Bishop Abraham” from the Dalem Museum , Berlin, the icon "Christ and St. Mina" from the Louvre). A different, non-ancient, artistic language was characteristic of the eastern regions of Byzantium - Egypt, Syria, Palestine. In their iconography, expressiveness was initially more important than knowledge of anatomy and the ability to convey volume [1] .

The process of changing ancient forms and their spiritualization by Christian art can be clearly seen in the example of the mosaics of the Italian city of Ravenna , the largest ensemble of early Christian and early Byzantine mosaics that has survived to our time. The mosaics of the 5th century (the mausoleum of Galla Placidia , the Orthodox baptistery ) are characterized by lively views of figures, naturalistic modeling of volume, and the picturesqueness of mosaic masonry. In the mosaics of the end of the 5th century ( Baptistery of the Arians ) and the 6th century (the basilica of Sant'Apollinare-Nuovo and Sant'Apollinare in Classe , the church of San Vitale ), the figures become flat, the lines of the folds of clothes are rigid, schematic. Poses and gestures freeze, the depth of space almost disappears. Faces lose a sharp personality, laying mosaic becomes strictly ordered [2] .

The reason for these changes was a purposeful search for a particular pictorial language capable of expressing Christian doctrine.

Iconoclast period

The development of Christian art was interrupted by iconoclasm , established as the official ideology of the empire since 730. This caused the destruction of icons and paintings in temples. Persecution of the iconographers. Many icon painters emigrated to the remote ends of the Empire and neighboring countries - to Cappadocia , to the Crimea , to Italy , and partly to the Middle East , where they continued to create icons. Although in 787 at the Seventh Ecumenical Council, iconoclasm was condemned as heresy and the theological justification of icon veneration was formulated, the final restoration of icon worship began only in 843. In the period of iconoclasm, instead of icons, only images of a cross were used in temples, decorative images of plants and animals were made instead of old murals, secular scenes were depicted, in particular horse races loved by the emperor Constantine V [3] .

Macedonian Period

After the final victory over the heresy of iconoclasm in 843, the creation of murals and icons for the temples of Constantinople and other cities began again. From 867 to 1056 in the Byzantine rule the Macedonian dynasty , which gave its name to the whole period, which is divided into two stages:

- Macedonian "Renaissance".

The first half of the Macedonian period is characterized by an increased interest in the classical antique heritage. The works of this time are distinguished by naturalness in the transfer of the human body, softness in the image of draperies, liveliness in faces. Vivid examples of classicized art are: the mosaic of Sophia of Constantinople with the image of Our Lady on the throne (mid-IX century), the icon-folding from the monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai with the image of the Apostle Thaddeus and King Avgar , receiving cards with the Sacred Image of the Savior (mid-X century) [4] .

In the second half of the 10th century, icon painting retains classical features, but icon painters are looking for ways to give images more spirituality.

- Ascetic style.

In the first half of the XI century, the style of Byzantine iconography changes dramatically in the direction opposite to the ancient classics. Several large ensembles of monumental painting survived from this time: frescoes of the Church of Panagia Tone Khalkeon in Thessaloniki in 1028, mosaics of the catholicon of the Osios Lukas monastery in Fokida in the 30–40s. The XI century, mosaics and frescoes of St. Sophia of Kiev of the same time, the murals of Sofia of Ohrid in the middle - 3 quarters of the XI century, the mosaics of Nea Moni on the island of Chios 1042-1056. and others [5] .

For all the listed monuments the limiting degree of asceticism of images is characteristic. Images are completely devoid of anything temporary and volatile. In the faces there are no feelings or emotions of any kind, they are extremely frozen, conveying the inner composure of those depicted. For this purpose, huge symmetrical eyes with a detached, fixed gaze are emphasized. Figures freeze in strictly defined poses, often acquire squat, heavy proportions. Hands and feet become heavy, rough. Modeling folds of clothes stylized, becomes very graphic, only conditionally conveys natural forms. Light in modeling acquires supernatural brightness, carrying the symbolic meaning of Divine Light.

The bilateral icon of Our Lady Odigitria with a well-preserved image of the Great Martyr George on the back (11th century, in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin), as well as many book miniatures, belong to this stylistic movement. The ascetic trend in icon painting continued to exist later, manifesting itself in the XII century. An example is the two icons of Our Lady Odigitria at Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos and the Greek Patriarchate in Istanbul [6] .

Comnenian period

The next period in the history of Byzantine icon painting falls on the rule of the Duk, Komnin and Angels dynasties (1059–1204). In general, it is called Komninovsky. In the second half of the 11th century, asceticism replaced the classical form and harmony of the image. The works of this time (for example, Daphne mosaics around 1100) reach a balance between the classical form and the spirituality of the image, they are elegant and poetic.

The creation of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God (TG) dates back to the end of the 11th century or the beginning of the 12th century. This is one of the best images of the Comnin era, certainly the work of Constantinople. In 1131-1132 the icon was brought to Russia, where it became particularly revered. From the original painting only the faces of the Mother of God and the Baby have survived. Beautiful, filled with subtle grief about the sufferings of the Son, the face of the Mother of God is a characteristic example of the more open and humanized art of the Komninian era. At the same time, in his example, one can see the characteristic physiognomic features of Komnin's painting: an elongated face, narrow eyes, a thin nose with a triangular fossa on the bridge of the nose.

By the first half of the 12th century, the mosaic icon “Christ Pantocrator Mercurer” from the Dalem State Museums in Berlin belongs. It expresses the internal and external harmony of the image, concentration and contemplation, the Divine and the human in the Savior.

In the second half of the 12th century, the icon “St. Gregory the Miracle-maker” from the State was created. Hermitage. The icon is distinguished by the magnificent letter of Constantinople. In the image of the saint, the individual beginning is especially strongly emphasized, we see a portrait of a philosopher [7] .

- Komninsky mannerism

In addition to the classical trend in the iconography of the XII century, there were other currents that are prone to violation of balance and harmony in the direction of greater spiritualization of the image. In some cases, this was achieved by increased expression of painting (the earliest example is the frescoes of the church of St. Panteleimon in Nerezi in 1164, the icons “ Descent into Hell ” and “ Assumption ” of the end of the XII century from the monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai).

In the latest works of the XII century, linear stylization of the image is extremely enhanced. And draperies of clothes and even faces are covered with a network of bright whitening lines that play a crucial role in the construction of the form. Here, as before, light has the most important symbolic meaning. The proportions of figures that become excessively elongated and thin are also stylized. Its maximum manifestation of stylization reaches in the so-called Late Carnism Mannerism. This term refers primarily to the frescoes of the church of St. George in Kurbinovo , as well as a number of icons, such as the " Annunciation " of the end of the XII century from the collection in Sinai. In these paintings and icons, the figures are endowed with sharp and rapid movements, the folds of clothes twist intricately, the faces have distorted, specifically expressive features [8] .

In Russia, there are also examples of this style, for example, the frescoes of the church of St. George in Staraya Ladoga and the turn of the icon " Savior, Not Made By Hands ", which depicts the worship of the angels to the Cross (TG).

XIII century

The heyday of iconography and other arts was interrupted by the terrible tragedy of 1204. This year, the knights of the Fourth Crusade captured and terribly plundered Constantinople . For more than half a century, the Byzantine Empire existed only as three separate states with centers in Nicaea , Trapezund and Epirus . The Latin Crusader Empire was formed around Constantinople. Despite this iconography continued to evolve. The thirteenth century was marked by several important stylistic phenomena.

At the turn of the XII-XIII centuries in the art of the whole Byzantine world there is a significant change in stylistics. Conventionally, this phenomenon is called "art around 1200". In place of linear stylization and expression, calm and monumentalism come to iconography. Images become large, static, with a clear silhouette and sculptural, plastic form. A very characteristic example of this style are the frescoes in the monastery of St.. St. John the Divine on the island of Patmos . By the beginning of the XIII century, a number of icons from the monastery of St.. Catherine in Sinai : " Christ Pantokrator ", mosaic "Our Lady Odigitria ", " Archangel Michael " from Deesis, "Sts. Theodore Stratelates and Dimitri of Solun . In all of them, features of the new direction appear, making them different from the images of the Comnenian style.

At the same time, a new type of icons appeared - living. If earlier scenes from the life of one or another saint could be depicted in illustrated Minology, on epistyle (long horizontal icons for altar barriers ), on folds of triptychs, now scenes from the life (“stigma”) were placed around the perimeter of the center of the icon, which depicts saint himself. In the collection in Sinai the living icons of St. Catherine (full-growth) and St. Nicholas (half-length) are preserved.

In the second half of the 13th century, classical ideals dominated in iconography. In the icons of Christ and Our Lady of Hilandar on Athos (1260s) there is a regular, classical form, the painting is complex, nuanced and harmonious. There is no tension in the images. On the contrary, the lively and concrete view of Christ is calm and affable. In these icons, Byzantine art approached the degree of closeness of the Divine to the human as possible. In 1280–1290 Art continued to follow the classical orientation, but at the same time, it appeared a special monumentality, power and emphasis of the techniques. In the images showed heroic pathos. However, due to excessive intensity, harmony somewhat decreased. A striking example of the iconography of the late 13th century is the Evangelist Matthew from the gallery of icons in Ohrid .

- Crusader workshops

A special phenomenon in the iconography are workshops created in the east by the Crusaders. They combined the features of European ( Romanesque ) and Byzantine art. Here, Western artists adopted the techniques of Byzantine writing, while Byzantines made icons that were close to the tastes of the Crusader customers. The result was an interesting fusion of two different traditions, variously intertwined in each individual work (for example, the frescoes of the Cypriot Church of Antiphonitis ). Crusader workshops existed in Jerusalem , Acre , Cyprus and Sinai [9] .

Palaeologic period

The founder of the last dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, Mikhail VIII Paleologue , in 1261 returned Constantinople to the hands of the Greeks. His successor on the throne was Andronicus II (reigned 1282–1328). At the court of Andronik II, exquisite art flourished magnificently, corresponding to the chamber court culture, which was characterized by excellent education, an increased interest in ancient literature and art.

- The Palaeologo Renaissance - this is what is usually called the phenomenon in the art of Byzantium in the first quarter of the 14th century.

While preserving its ecclesiastical content, the iconography acquires extremely aesthetic forms, experiencing the strongest influence of the ancient past. It is then that miniature mosaic icons are created, intended either for small, chamber chapels, or for noble customers. For example, the icon of "St. Theodore Stratelates " in the collection of the GoE . The images on such icons are unusually beautiful and amaze by their miniature work. The images are either calm, without psychological or spiritual depth, or, on the contrary, sharply characteristic, as if portrait. Such are the images on the icon with four saints, also located in the Hermitage.

There are also a lot of icons written in the usual, tempera technique. They are all different, the images are never repeated, reflecting different qualities and states. Thus, in the icon “The Mother of God of Psycho-Astrology (Soul-Savior)” from Ohrid , firmness and strength are expressed, in the icon “The Mother of God Odigitria” from the Byzantine Museum in Thessaloniki opposite lyricity and tenderness are conveyed. “The Annunciation” is depicted on the back of “Our Lady of Psychostration”, and on the back of her icon of the Savior on the back is written “Crucifixion of Christ”, in which pain and sorrow, overcome by the power of the spirit, are acutely conveyed. Another masterpiece of the era is the icon "The Twelve Apostles" from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts. Pushkin . In it, the images of the apostles are endowed with such a bright individuality that it seems that we have before us a portrait of scientists, philosophers, historians, poets, philologists, and humanities who lived in those years at the imperial court.

For all the listed icons, impeccable proportions, flexible movements, impressive posing of figures, stable postures and easily readable, verified compositions are characteristic. There is a moment of entertainment, concreteness of the situation and the stay of the characters in space, their communication [10] .

In the monumental painting similar features were clearly manifested. But here the Paleologo era brought especially many innovations in the field of iconography. A lot of new plots and detailed narrative cycles appeared, the programs became saturated with complex symbols related to the interpretation of Holy Scripture and liturgical texts. Complex symbols and even allegories began to be used. Two ensembles of mosaics and frescoes of the first decades of the 14th century have been preserved in Constantinople — in the monastery of Pommakaristos ( Fity-jami ) and the monastery of Chora ( Kahriye-jami ). In the depiction of various scenes from the life of the Mother of God and from the Gospel , previously unknown stage versions, narrative details, and literature have appeared.

- The period of controversy about the light of Tabor

In the 30-40 years. In the 14th century, the situation in the spiritual life of Byzantium changed, which immediately affected the character of icon painting.

The era of the "Renaissance" in art and the courtly humanistic culture is over. It was then that a dispute arises between the monk Varlaam , who came to Constantinople from Calabria in Italy, and Gregory Palamas , a scientist-monk from Athos . Barlaam was brought up in a European environment and essentially differed from Gregory Palamas and the Athonite monks in matters of spiritual life and prayer. They fundamentally differently understood the tasks and possibilities of man in communion with God. Barlaam adhered to the side of humanism and denied the possibility of any mystical connection between man and God . Therefore, he denied the practice of Hesychasm on Athos, an ancient Eastern Christian tradition of prayer making. Athos monks believed that when they prayed, they see the Divine light - the same one that the apostles saw on Mount Tabor at the moment of the Transfiguration of the Lord . This light (called Favorite) was understood as a visible manifestation of uncreated Divine energy permeating the whole world, transforming man and allowing him to communicate with God . For Barlaam, this light could have an exclusively creaturely character, and there could be no direct communication with God and the transfiguration of man by divine energies. Gregory Palamas defended Hesychasm as a primordially Orthodox teaching on the salvation of man. The controversy ended in victory for Gregory Palamas. At the cathedral in Constantinople of 1352, hesychasm was recognized as true, and the Divine energies uncreated, that is, manifestations of God himself in the created world.

For the icons of the time of disputes, tension in the image is characteristic, and in artistic terms, there is a lack of harmony, only recently so popular in the refined court art. An example of the icon of this period is the belt deesis image of John the Forerunner from the Hermitage collection [11] .

- Second half of the 14th century

In the 50s. XIV century Byzantine iconography is experiencing a new rise, based not only on the classical heritage, as it was in the decade of the "Paleologovskogo Renaissance", but especially on the spiritual values of the victorious Hesychasm. From the icons go the tension and gloominess, which appeared in the works of 30-40 years. However, now the beauty and perfection of form are combined with the idea of the transfiguration of the world by divine light. The theme of light in the painting of Byzantium always somehow took place. Light was understood symbolically as a manifestation of the Divine power permeating the world. And in the second half of the XIV century, in connection with the teachings of Hesychasm, such an understanding of the light in the icon became all the more important.

The “Christ Pantocrator” icon from the Hermitage collection is a beautiful piece of the era. The image was created in Constantinople for the monastery of Pantocrator on Mount Athos , the exact year of its execution is known - 1363. The image surprises with both the external beauty of painting, perfection in conveying the shape of faces and hands, and the very individual image of Christ, close and open to man. The paints of the icon seem to be pierced with internal luminescence. In addition, the light is depicted in the form of bright whitening strokes, lying on the face and hand. In this way, the pictorial reception conveys the doctrine of uncreated Divine energies that permeate the whole world. This technique is made particularly common.

After 1368, an icon was painted by St. Gregory Palamas himself (Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts), famous in the face of saints. His image also differs in enlightenment, individuality (literally portraiture) and contains a similar technique of whitening "engines" or "lights."

The icon of the Archangel Michael from the Byzantine Museum in Athens , the icon of Our Lady Perivepty, stored in Sergiev Posad and many others, is close to the image of Christ from the GE. The painting of some is rich in rich colors, while others are somewhat more strict.

The weakness of the Byzantine Empire and the danger of the Turkish conquest contributed to the great emigration of artists. During this period, Byzantine masters carry out orders in various parts of the Orthodox world, including Russia. Due to this, in domestic collections many first-class Byzantine icons of this time are kept.

In Russia, a huge icon was created “Praise to Our Lady”, surrounded by stamps illustrating the Akathist (stored in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin). The painting of the icon is distinguished by its brightness, unusually moving figures, very individual faces with sharp sparkling glances. The temperament of performance was especially expressed in flashes of whitening strokes. The iconography of this era is generally characterized by elevated intonations and, as never before, heightened emotionality (the quality of icon painting is very restrained).

In the 80-90 years. The 14th century created a large Deesis rank consisting of 7 belt icons and ordered in Constantinople for the Vysotsky monastery in Serpukhov . Currently, 6 of these icons are stored in the State Tretyakov Gallery ("John the Baptist" in the State Russian Museum). This is an example of a classic, beautiful in art form, joyful and enlightened in its content. In Vysotsky rank shakes a huge scale of figures and the grandeur of a clear, large form. At the same time, psychologization of the image becomes deeper.

Undoubtedly, the Greek work attributed to Theophanes the Greek , are icons from the height of the Deesis rank of the end of the XIV century, now standing in the iconostasis of the Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. They are even bigger and more majestic than icons from the Vysotsky monastery. The image of the Virgin of this order is very similar to the Don Icon of the Mother of God , also attributed to Theophanes. The Don Icon is distinguished by greater softness of the performance and the intimacy of the images.

Chamber direction existed in parallel with large monumental images. This includes the image of Our Lady of Pimenovskoy (80s of the XIV century, the Tretyakov Gallery). The fragility of the forms and the delicacy of color soften the classic form. The icon has an unusually large amount of warm emotional feeling that has replaced the accepted concentration of images.

- Art of the beginning of the XV century.

In the last decades before the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453, artistic life in Byzantium did not slow down its intensity. It continued to exist different in nature of the flow.

The classical jet was manifested in beautiful enlightened images, for example, in the icon of Anastasia the Patterns Women from the GoE, the work of the Constantinople or Thessalonian master. Her colors are especially tender, and her face is fresh in her youth.

The art of a different plan is represented by the icon “Crucifixion” ( Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin ). The iconography is extremely detailed. The entire image plane is filled with many scenes, groups, and individual figures. By execution, this icon refers to the expressive flow. Thanks to the condensed, darkened color and glare of light, boldly thrown at the depicted figures, the icon created a tense atmosphere corresponding to the tragedy of the depicted plot. The characteristic features of the first half of the 15th century are the smallness of the forms, the fragility of proportions, thin and flexible lines of gaps. All this creates a special expressiveness, even piercing images, characteristic of the XV century.

On the contrary, an example of beauty and harmony is given by the small icon “Trinity” from the collection of the GoE. The perfectly constructed composition with flowing lines flowing into each other, and the sonorous bright color in this icon create a feeling of unearthly beauty [12] .

The best qualities of Byzantine art from the beginning of the 15th century were embodied in the work of the great Russian icon painter, Rev. Andrei Rublev .

Ancient Russia

The beginning of Russian icon painting was laid after the Baptism of Rus . Originally, the oldest Russian stone churches in Kiev and other cities, as well as their paintings and icons, were created by Byzantine masters. However, already in the 11th century, there was an iconographic school of its own in the Kiev-Pechersk Monastery, which gave the first well-known icon painters - the Rev. Alipii and Gregory .

The history of ancient Russian art can be divided into " pre-Mongol " and subsequent, since the historical circumstances of the XIII century significantly influenced the development of the culture of Russia.

Although in the XIV century the influence of Byzantium and other Orthodox countries on Russian icon painting was great, Russian icons even earlier showed their own original features. Многие русские иконы являются лучшими образцами византийского искусства. Другие — созданные в Новгороде , Пскове , Ростове и других городах — очень своеобразны, самобытны. Творчество Андрея Рублева является одновременно и прекрасным наследием традиций Византии и объемлет в себе важнейшие русские черты.

Сербия, Болгария, Македония

В Болгарском средневековом искусстве иконопись появилась одновременно с принятием христианства в 864 году. Первообразом была византийская иконопись, но вскоре она смешалась с существующими местными традициями. Достаточно уникальны керамические иконы. На основу (керамическая плитка) наносился рисунок яркими красками. От византийской школы иконописи эти иконы отличались большей округлостью и живостью лица. Из-за хрупкости материала до нашего времени дожило очень мало произведений в этом стиле, к тому же от большей части остались только фрагменты. В эпоху Второго Болгарского царства в иконописи существовали два основных течения: народное и дворцовое. Первое связано с народными традициями, а второе берет своё начало от Тырновской художественной школы живописи, на которую оказывало большое влияние искусство ренессанса. Наиболее часто встречающийся персонаж в болгарской иконописи — Святой Иоанн Рыльский. В те времена, когда Болгария была частью Османской империи, иконопись, славянская письменность и христианство помогли сохранить народное самосознание болгар. Национальное Возрождения Болгарии привнесло некоторое обновление в иконопись. Новый стиль, близкий народным традициям, не противоречил основным канонам жанра. Яркие, жизнерадостные цвета, персонажи в костюмах современной эпохи, частое изображение болгарских царей и святых (позабытых во времена османского ига) являются отличительными чертами иконописи болгарского Возрождения.

Современное состояние иконописи

Иконописцы:

- Соколова, Мария Николаевна (монахиня Иулиа́ния)

- Ватагина, Ирина Васильевна

- Волочкова, Ирина Владимировна

- Зинон (Теодор)

- Айнетдинов, Александр

- Эйтенейер, Анатолий

See also

- Icon

- Иконография Спасителя

- Иконография Богородицы

- Иконостас

- Части иконной доски

- Древнерусское лицевое шитье

Notes

- ↑ История Иконописи. Origins. Традиции. Современность. М., «АРТ-БМБ», 2002, с. 44—48

- ↑ Галина Колпакова . Искусство Византии. Early and middle periods. СПб., «АЗБУКА-КЛАССИКА», 2004, с. 128—167

- ↑ История Иконописи. Origins. Традиции. Современность. С. 48—49

- ↑ История Иконописи. Origins. Традиции. Современность. С. 49—50

- ↑ Галина Колпакова. Искусство Византии. Early and middle periods. С. 313—343

- ↑ История Иконописи. Origins. Традиции. Современность. С. 51—52

- ↑ История Иконописи. Origins. Традиции. Современность. С. 53—59

- ↑ История Иконописи. Origins. Традиции. Современность. С. 59—65

- ↑ История Иконописи. Origins. Традиции. Современность. С. 66—76

- ↑ История Иконописи. Origins. Традиции. Современность. С. 76—80

- ↑ История Иконописи. Origins. Традиции. Современность. С. 80—81

- ↑ История Иконописи. Origins. Традиции. Современность. С. 76—93

Links

- Техника иконописи

- Византийская иконопись на сайте «Образ в христианском искусстве»

- Виртуальный каталог икон, иконописные школы. Иконы Древней Руси XI—XVI веков.

- Каталог «Православное христианство». Раздел «Иконопись».

- История иконописи. Хронологическая таблица.

- Техника иконописи. Руководство к практическому изучению писания православных икон по приемам первых иконописцев. Общество «Икона» в Париже.

- С. М. Прохоров. Журнал «Светильник». 1913, № 1.

- П. А. Флоренский. ИКОНОСТАС. - Метафизические различия между писаной темперой и в каноне иконой и её масляным аналогом, исследовал и показал выдающийся русский мыслитель, философ и священник о. Павел Флоренский.

- Словарь русских иконописцев XI-XVII вв.

Literature

- ed. Т. В. Моисеева. История Иконописи. Origins. Traditions. Современность. М., «АРТ-БМБ», 2002. 290 с. ISBN 5-901721-12-8

- Н. П. Кондаков Иконография Богоматери. Связи греческой и русской иконописи с итальянской живописью раннего Возрождения. М. «Паломникъ». 1999. 224 с. Репринт. Санкт-Петербургъ. Товарищество Р. Голике и А. Вильборгъ. 1910.

- Покровский Н. В. Очерки памятников христианского искусства. СПб.: «Лига Плюс», 2000. 412 с., с илл. ISBN 5-93294-001-8

- Монахиня Иулиания (Соколова). Труд иконописца. Изд-во Троице-Сергиевой Лавры, 1999.

- Филатов В. В. Реставрация станковой темперной живописи. — М., 1986.

- Замятина Н. А. Терминология русской иконописи. 2nd ed. — М.: Языки русской культуры, 2000. 272 с. — (Язык. Семиотика. Культура. Малая серия.) ISBN 5-7859-0070-X

- Rauschenbakh BV Spatial constructions in painting. Sketch of the main methods. M.: Nauka, 1980. 288 p., Ill.

- O. S. Popova. Problems of Byzantine art. Mosaics, frescoes, icons. M. "Northern Pilgrim", 2006

- VD Sarabyanov, ES Smirnova. The history of ancient Russian painting. M. Orthodox St. Tikhon University of Humanities, 2007.

- Starodubtsev OV Russian Church Art of the 10th-20th Centuries. M.: Lepta Book, Publishing House Sretensky Monastery, 2007.