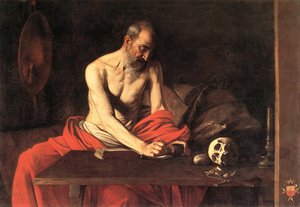

“The Writing Saint Jerome” is a painting by Caravaggio painted around 1607-1608, during the artist’s stay in Malta . The canvas depicts Saint Jerome , who is engaged in his cell translating the Bible from Greek into Latin . There is an earlier version of the picture, with a fundamentally different composition, currently located in the Borghese Gallery in Rome . From the 17th century to this day, the painting has not left the island (with the exception of several temporary exhibitions) and is now kept in the Cathedral of St. John in the capital of Malta Valletta . In 1984, the painting was stolen, but after 4 years it was returned and at the end of the 20th century it underwent a complete restoration.

| ||

| Caravaggio | ||

| The Writing Saint Jerome . OK. 1607-1608 | ||

| ital. San girolamo scrivente | ||

| Canvas, oil. 117 × 157 cm | ||

| St. John's Cathedral , Valletta , Malta | ||

| ( inv. ) | ||

Description

The artist focuses all the viewer's attention on the central figure of the writing Jerome, unlike the earlier Roman version, the horizontal composition of which is formed by the saint's hand extended to the book [2] . Caravaggio uses a limited palette of colors to emphasize the severity and seriousness of the scene [3] . The picture is dominated by only three tones: the dark brown atmosphere of the room, the flesh color of Jerome left illuminated on the left and the red toga of the saint falling from his shoulders [4] .

The composition of the picture is formed on the one hand by the central triangle, the sides of which are the saint's pose and the robes that fell from him, and on the other, with the lines of the direction of his hands and gaze [4] . The dynamics of the center is stabilized by the vertical and horizontal lines of the table, bed, walls and a hat hanging on the wall [5] . Three degrees of depth of the picture are determined by the background with a bed and a wall, the middle - with Jerome writing at the table and the foreground - with the crucifix serving as a link between the saint and the spectator [2] .

Despite the scarcity of the scene, art historians note its rich iconography , including red clothes and a cardinal hat, a stone, a skull, a crucifix, a manuscript of Jerome, to which Caravaggio adds an extinct candle [6] . Each of the elements carries its own symbolism, relating both to the traditional iconography associated with Jerome, and to the specifics of this particular scene. Red robes and a hat indicate the cardinal dignity of Jerome [2] ; the crucifix, as the highest symbol of Christianity, serves as a bridge between the viewer and St. Jerome [2] , materializing his faith; the book symbolizes theological knowledge; Saint Jerome tortured himself with a stone in the desert, considering the strength of his fist insufficient to repent [6] ; the skull is a necessary element of vanitas , and the candle with it serves as a reminder of the transience of human life [7] . An extinguished candle does not interfere with the creative activity of the saint, and the light that floods his body can symbolize the divine presence [5] .

Caravaggio captured the moment of deep immersion of Jerome in work. His mouth is ajar, as if he is making aloud the recorded thoughts [8] , his pose is almost on the verge of physiological unnaturalness, but he is so keen on work that he does not notice this, as well as the toga that has fallen from his shoulders [5] . The play of light creates a defining contrast between the brightly lit body of the saint and the soft dusk surrounding him, which emphasizes the dramatic intensity of the scene, enhanced by the effect of the open door, which the artist creates with the help of the door jamb on the right, as if allowing the viewer to look inside the dark enclosed space [2] .

The art critic Matteo Marangoni at the beginning of the 20th century praised the work as one of the most remarkable achievements of the master [9] : he was particularly delighted with the distribution of light in the picture, thanks to which the illuminated forms appear smoothed [9] . "Writing Saint Jerome", created in Malta, is considered a deeply introspective work for Caravaggio [10] - perhaps the calmness and tranquility of the painting are a reflection of the state of the artist himself after the turmoil of Italian life [11] .

History

Caravaggio arrived in Malta on July 12, 1607. He spent the previous months in Naples, where he sought refuge from his influential patrons, the Colonna family, after killing a man during a street fight in Rome a year earlier. In Naples, he quickly gained success by receiving dozens of orders, including several major altar works, and breathing caravagism into local artists. The exact reasons that made him leave Naples are unknown. He still remained a criminal who was threatened with persecution of the relatives of the murdered man, and his Naples patrons, who had strong ties to the Order of Malta , may have considered that joining the order would give the artist better protection and help in obtaining papal pardon for returning to Rome, and The great master Alof de Vinyakur , who sought to increase the prestige of his order, found an attractive prospect to get one of the leading Italian artists.

The coat of arms depicted in the lower right corner of the painting belongs to the customer of the painting, Ippolito Malaspin [12] , the Prior of the Order of Malta in Naples, a relative of Ottavio Costa, the patron saint of Caravaggio, and a friend of the Genoese admiral Andrea Dori, who provided the artist with protection after fleeing from Rome. The choice of theme seems a little strange for someone who devoted his life to fighting the Turks, but Malaspina was not only a famous warrior, but also the patron of the poor, orphans and widows, therefore, the picture could be designed to emphasize both this aspect of his work and asceticism orders.

Art historians put forward various assumptions as to who served as the model for the image of St. Jerome. For a long time it was believed that it was Alof de Vinyakur, and for some time the picture was called “Vinyakur in the image of St. Jerome” [2] . However, the saint’s similarity with other portraits of Vinyakur is relative, which allows us to put forward other hypotheses, for example, that Malaspina himself could be a model [6] or that Caravaggio did not seek to depict a specific person at all [13] .

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 http://finearts.heritagemalta.org/artifact.aspx?id=53

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Catherine Puglisi, c. 281

- ↑ Cynthia Degiorgio, c. ten

- ↑ 1 2 Cynthia Degiorgio, c. eleven

- ↑ 1 2 3 David M Stone, c. four

- ↑ 1 2 3 Graham-Dixon, c. 371

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, c. 218–219

- ↑ David M Stone, c. five

- ↑ 1 2 André Berne-Joffroy c. 295)

- ↑ David M Stone, c. 3

- ↑ Cynthia Degiorgio, c. 10-11

- ↑ Vodret, p. 180

- ↑ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, c. 218

Literature

- André Berne-Joffroy, Le Dossier Caravage: Psychologie des attributions et psychologie de l'art, Paris, Flammarion, coll. Champs arts, 2010

- Cynthia Degiorgio, “Caravaggio's St Jerome Writing”, Treasures of Malta, vol. 12, no 2, 2006

- Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, Caravage, Paris, éditions Hazan, 2009

- Andrew Graham-Dixon, “Caravaggio: a life sacred and profane” London, Allen Lane, 2010

- Catherine Puglisi “Caravage”, Paris, éditions Phaidon, 2005

- David M. Stone et Keith Sciberras, "Malaspina, Malta, and Caravaggio's 'St. Jerome'", Paragone, no 60, mars 2005

- Rossella Vodret Caravage, “l'œuvre complet”, Silvana Editoriale, 2010