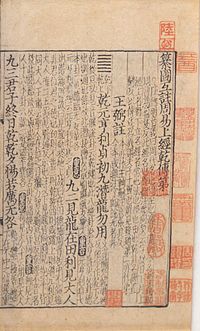

“I Ching” ( Chinese trad. 易經 , ex. 易经 , pinyin : Yì Jīng ), or “Zhou I” [1] (周易) is the earliest of Chinese philosophical texts. The earliest layer, traditionally dated to approx. 700 BC n e. [2] and intended for fortune telling, consists of 64 hexagrams . In the II century BC e. was adopted by Confucian tradition as one of the canons of the Confucian Pentateuch .

| This page or section contains text in Asian languages. If you do not have the required fonts , some characters may not display correctly. |

| And jing Book of Changes | |

|---|---|

And jing | |

| Author | Fu xi |

| Original language | |

Book of Changes | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| traditional chinese : | 易經 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese : | 易经 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| pinyin : | Yì Jīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Value: | "Canon of Changes" | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

“The Book of Change” is the name assigned to “I Ching” in the West. A more correct, albeit not so harmonious, version is “Cannon Change” .

Content

- 1 Background

- 2 Contents of the work

- 3 Hexagram system

- 4 Location of hexagrams

- 5 Book of Changes in Confucianism

- 6 Comments and development

- 6.1 “Ten Wings”

- 7 See also

- 8 Notes

- 9 Literature

- 10 Links

Background

Zhou is not the most ancient fortune-telling system in Chinese history. Guo yu (ep. Warring States), Zhou li (Qin-Han), as well as medieval texts mention her previous works (practices?): “Lien Shan” 《連山》 ep. Xia and Guizang 《歸 藏》 ep. Shang Yin. As in the case of Zhou and , tradition connects them with the “losh” diagram, but nothing is known about them besides the names.

The content of the work

The existing system of the Book was formed mainly during the Zhou Dynasty and, unlike the mantle systems of earlier times, it is called the “Zhou Book of Changes” .

It consists of 64 symbols - hexagrams , each of which expresses a particular life situation in time in terms of its gradual development. Symbols consist of six traits ; traits indicate successive stages in the development of a given situation. Traits, also called yao , are of two kinds: either whole (they are also called nines ), or interrupted in the middle ( sixes ) (there is also a color difference between the traits, for example, “nines” are indicated in white, “sixes” in black). This is due to the fact that the former symbolizes an active state, light, tension (yang) , and the latter - a passive state, darkness, suppleness (yin) . It is generally accepted that traits are read from the bottom up (although the opposite interpretation is also encountered); their sequence describes the development of the situation.

Each hexagram can also be represented as a combination of two trigrams , but in general combinations of traits yao have the common name gua . Each hexagram, as well as each line in the hexagram, is accompanied by a set of aphorisms , which should give advice to the fortuneteller. Fortune telling consists in choosing, using rather complicated pseudorandom procedures, using coins or yarrow twigs, six traits and searching for the corresponding hexagram in the book (for more details, the process of fortune telling using yarrow is described in Си 传 xìcí zhuàn) , comments, part of the so-called “wings” of the book of changes).

Hexagram System

| Kun (Earth) | Gen (Mountain) | Kanye (Water) | Sun (Wind) | Zhen (Thunder) | Lee (Fire) | Dui (Pond) | Qian (Sky) | ← Upper Trigram ↓ Lower trigram |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Tai | 26. Yes-chu | 5. Xu | 9. Xiao-chu | 34. Da Zhuan | 14. Yes | 43. Guay | 1. Qian | Qian (Sky) |

| 19. Lin | 41. Sun | 60. Jie | 61. Jung Fu | 54. Gui-mei | 38. Kui | 58. Dui | 10. Lee | Dui (Pond) |

| 36. Min-i | 22. Bi | 63. Ji-ji | 37. Jia Ren | 55. Fyan | 30. Lee | 49. Ge | 13. Tong Ren | Lee (Fire) |

| 24. Fu | 27. And | 3. Zhun | 42. And | 51. Zhen | 21. Shih-ho | 17. Sui | 25. U-van | Zhen (Thunder) |

| 46. Sheng | 18. Gu | 48. Jing | 57. Sun | 32. Han | 50. Dean | 28. Yes | 44. Gow | Sun (Wind) |

| 7. Shi | 4. Maine | 29. Kanj | 59. Huan | 40. Jie | 64. Wei-ji | 47. Kun | 6. Song | Kanye (Water) |

| 15. Qian | 52. Gen | 39. Jian | 53. Jian | 62. Xiao-go | 56. Lu | 31. Xian | 33. Dun | Gen (Mountain) |

| 2. Kun | 23. Bo | 8. Bi | 20. Guan | 16. Yu | 35. Jin | 45. Tsui | 12. Pi | Kun (Earth) |

Location of hexagrams

Mathematicians The Book of Changes is primarily interested in terms of the order of arrangement of hexagrams in it. Historically known hexagram arrangement orders: Fu Xi, Wen Wang, English. King_Wen_sequence (pictured above) and somewhat exotic. It is still not known until the end whether these hexagrams are randomly arranged in each such order or according to some law. But some patterns were revealed.

For example, if in order of Wen Wang, hexagrams are arranged in the order of their numbering, we get the following picture:

You can see that each even hexagram is obtained by turning the odd hexagram in front of it 180 °. If an even hexagram is symmetric with respect to rotation (that is, it turns into itself during rotation), then it is obtained from the odd hexagram in front of it by replacing all solid lines in this odd hexagram with broken lines and broken lines with solid lines. Thus, all hexagrams can be divided into pairs, the first type of pairs is highlighted in red, and the second type is highlighted in blue.

The American writer, philosopher and ethnobotanist Terence Mackené was able to find something that has eluded the attention of other I-ching scholars. Studying the order of Wen Wang, he decided to investigate how many features change during the transition from each previous hexagram to each following:

In this diagram, the first number is the number six - this is the number of lines that changed during the transition from the first hexagram to the second. And indeed, six solid lines were replaced by six intermittent ones. When moving from the second hexagram to the third, two intermittent lines changed to two solid lines - they got the number two. And so on.

Terence Macken noted that the number of all even numbers is 48, and all the odd numbers are 16 (a total of 64 numbers). Therefore, their ratio is 16/48 = 1/3. Terence Macken made very far-reaching conclusions from his discovery. Arguing that this attitude was not accidental, he developed the English software package . Terence_McKenna # Novelty_theory based on fractal geometry [3] (and, of course, based on its discovery) and using its program made several predictions, including “predicted” the end of the world in 2012 . However, mathematicians are inclined to believe that the Mackenna formula is more numerological [4] than mathematical. In other words, Macken took his predictions from other sources, in particular, from the Mayan calendar , and adjusted his “temporary wave” for them, choosing the necessary parameters. In his interview [5], Terence Mackena claims that Ixing hexagrams are indivisible elements of time, elements of the Tao flow, and the Book of Changes itself is a kind of periodic system of time elements. The discovery of Terence McKenna has never been published in print and exists only in electronic form on his personal website [6] .

In general, there are many mathematical laws identified in the location of hexagrams. But it should be taken into account, if one still relies on the generally accepted terminology of mathematics, that not a single regularity explains why and how Wen Wang constructed the existing order of hexagrams of the Book of Changes. Numerous traditions and comments that literally build up the whole system of Chinese traditional philosophy, the system of meanings and concepts do not explain it to us. The key to his understanding is contained in the work of Yu. K. Schutsky, “The Chinese Classical Book of Changes and Ching”, where the most authoritative scientist-translator revealed “mantle formulas of the first layer of the Book of Changes”. The author’s shooting in 1937 made it impossible to identify the mathematical structures of the sums of the mantle formulas of the first layer, manifested in the classical square of the Fu Xi hexagrams. This generalization, easily verified by direct substitution, is also confirmed by the presence of the same structures in the classical square (namely, as a geometric figure) of dodecagrams (dodeca - twelve, Greek.) Fu Xi.

Book of Changes in Confucianism

Confucius so appreciated the significance of this work: “If I could extend my life, I would give fifty years to study the Changes, and then I could not make mistakes” ( Conversations and Judgments 7.16). But it should be borne in mind that the “Book of Changes” is mentioned in “Conversations and Judgments (Lunyu)” only once, and is atypical for the interests of Confucius, who was not interested in the irrational: “I am not talking about the supernatural, about violence, about unrest and about spirits ”(“ Lunyu ”, VII, 21/22) There is an opinion that in reality Confucius did not speak of the“ Book of Changes ”at all, and the above quote is a consequence of the copyist's mistake. Moreover, the “Book of Changes” is not mentioned either in “Da Xue”, or in “Zhong Yun”, nor in Mencius, but in “Zuo Zhuang” and in Xunzi it is mentioned, but not as a Confucian classic text. These and other facts give grounds for some researchers to share the thought of the synologist Tsuda Sokiti that the “Book of Changes” was adopted not by Confucius, but by Confucians many years after his death. There are more radical points of view, for example, Honda Nariyuki believes that due to damage to the text, the word “易” (“[Book] of changes”) mentioned in Lunyu is only a slip of the pen instead of “亦” (“also”).

The book of changes is in first place among the classic books of Confucianism and in bibliographic reviews of Chinese literature. This is understandable, since bibliology and bibliography in feudal China were created by people who received a traditional Confucian education. The bibliographers of old China unshakably believed in a tradition (not primordial, but old enough), which attributed the creation of the Book of Changes to such antiquity that no other classical book could compete with it in chronological primacy, although in fact the Book of Changes is not the most ancient of the monuments of Chinese writing, and this was established by the Chinese philology.

Comments and development

- Yang Xiong扬雄 used the Book of Changes principle in his Taishuanjing treatise, but instead of binary opposition, he explored a combination of three characters (Heaven, Earth, Man): a solid line (1), a line with one space (2) and a line with two spaces (3).

Ten Wings

Comments on the book of changes are known as “ Ten Wings ” (十 翼, Shi and ):

- 彖 上傳 “Tuan Zhuan” (first), “The first comment of statements”

- 彖 下 傳 “Tuan Zhuan” (second), “Second commentary on the statements”

- 象 上傳 “Xiang Zhuan” (first), “First Commentary on Images”

- 象 下 傳 “Xiang Zhuan” (second), “Second Commentary on Images”

- 繫辭 上傳 " Sitsi Zhuang " (first), "The first comment of aphorisms"

- 繫辭 下 傳 “Sitsi Zhuan” (second), “Second comment of aphorisms”

- 文 言傳 “Wenyan Zhuan”, “Commentary on Signs and Words”

- 序卦 傳 “Xuigua Zhuan”, “Commentary on the sequence of hexagrams”

- 說 卦 傳 “Shogua Zhuan”, “Commentary on the explanation of trigrams”

- 雜 卦 傳 "Zagua Zhuan" "Various comments about hexagrams"

See also

- Ancient African fortune telling ifa

Notes

- ↑ Presumably, by the name of the Zhou era, during which the most authoritative edition of the book was compiled. According to another explanation, the hieroglyph 周 (zhou) here means “cycle, circuit”, and the hieroglyph 易 (i) - “change”, thus the name “Zhou I” means the cyclical nature of change.

- ↑ The article "I Ching" in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia .

- ↑ “The Mathematics of Timewave Zero”

- ↑ "Novelty_theory"

- ↑ “Interview with Terence Mackenna”

- ↑ "Terence McKenna's Timewave Zero Theory"

Literature

- Alekseev V. M. Comments on the book-dissertation by Yu. K. Schutsky Chinese classical “Book of Changes” // Alekseev V. M. Science about the East. M., 1982. S.371-388.

- Ageev N. Yu. On the problem of the emergence of calendar interpretations of I Ching // Society and the State in China. XXXII scientific conference. M., 2002.

- Ageev N. Yu. I Ching and the Calendar in the Works of Han Scientists // Society and State in China: XXXIX Scientific Conference / Institute of Oriental Studies RAS. - M., 2009. S.434-449.- ISBN 978-5-02-036391-5 (in the region)

- Appenyansky A. I. I Ching Counseling. - M.: Publishing House of the Institute of Psychotherapy, 2002.-583 p.

- Davydov S. D. On the order of hexagrams in the “Book of Changes”. // XIX Tax Code of OGK. M., 1988.

- Zinin S. V. "I Ching" as a Monument to Chinese Literature. // Petersburg Oriental Studies. 1993. Issue 3.

- Emelyanov S. S. On the reconstruction of the spatial composition of hexagrams. // XX Tax Code of OGK. M., 1989.

- Eremeev V.E. Arithmosemiotics “Books of Changes.” - M.: Sputnik + Company, 2001. 152 p.

- And jing. "Book of Changes" and its canonical comments / Perev. with China, foreword and note. V.M. Yakovleva.-M.: Janus-K, 1998.- 267 p.

- Eremeev V. Ye. Symbols and numbers of the “Book of changes”. 2nd ed., Rev. and add. — M.: Ladomir, 2005.600 s.

- Eremeev V.E. “Book of changes” and semantic coding // Problems of Philosophy . 2007. No. 5. P. 112—121.

- Karapetyants A. M. On the problem of the structure of “I Ching” // XIV Scientific Conference. Society and state in China. Part 1., M., 1983.

- Karapetyants A. M. The problem of the structure of “Zhou and” // 24th Scientific Conference “Society and the State in China”. Part I. M., 1993.

- Kobzev A. I. The doctrine of symbols and numbers in Chinese classical philosophy. - M .: Nauka, 1994.

- Krushinsky A. A. The Logic of “I Ching”: Deduction in Ancient China. M., VL. 1999.173 p.

- Lukyanov A. Ye. Tao “Books of changes”. M., 1993.

- Spirin V. S. Four types of “identity” in “Mo-tzu” and types of hexagrams “I ching” // Written monuments and problems of the history of culture of the peoples of the East. XXIV. Part 1. M., 1991.

- Wu Jin, Wang Yongsheng . One hundred answers to questions about "Zhou and." Per. from English - Kiev: Nika-Center, 2001.-312 p.

- Chibisov T. P. Tai xuan jing and hexagrams I jing // XXVIII scientific conference "Society and the state in China." M., 2007. S.178-185.

- Chibisov T.P. Zhou and the system of cyclic changes and tetragrams of Tai Xuan Jing // Society and State in China: XXXIX Scientific Conference / Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences . - M., 2009. S.406-419.- ISBN 978-5-02-036391-5 (in the region)

- Schutsky Yu. K. Chinese Classical “Book of Changes” / Ed. A.I. Kobzeva. 2nd ed. - Moscow: Nauka, 1993.

- Jung K. G. On the psychology of eastern religions and philosophies. - M.: 1994.

- Zhou Zonghua . Tao I Ching. Per. from English - K: Sofia, 1996, 1999. ISBN 5-220-00022-5

Tlaib, Rashida

Links

- Eremeev V. Ye. “Symbols and numbers of the Book of Changes”

- Ole Lukoe "I Ching." Reconstruction - Book of Changes as a Book of Universal

- I Ching (original in Chinese with baidu .com)