Neuroanatomy is a field of biological sciences that studies the anatomical structure ( structural neuroanatomy ) and the functional organization ( functional neuroanatomy ) of the nervous systems of various animals that possess it. Unlike animals with radial symmetry (for example, jellyfish ), in which the nervous system is a diffuse nervous network, animals with bilateral symmetry have separate, clearly anatomically and histologically delimited from other tissues , nervous systems. Therefore, their nervous systems are of great interest to scientists and are better understood. In all chordates, the nervous system is divided into the internal structures of the brain and spinal cord , collectively called the central nervous system , or CNS, and the peripheral nervous system , or PNS, which connects various structures of the central nervous system with the rest of the body via nerves , as well as an independent the enteric nervous system , in addition to the nerves of the peripheral nervous system, innervates the gastrointestinal tract . Homologous structures in arthropods and a number of other classes of invertebrate animals are called, respectively, the periopharyngeal nerve ring or central nerve node (central ganglion), and the central nervous axis (neuraxis), and the peripheral nervous system.

Neuroanatomy is both a subsection of neuroscience and a subsection of general anatomy, and thus lies at their junction. This article is devoted to the description of the study of neuroanatomy, its research methods, and the history of its development. For information on the anatomical structure and details of the functioning of the nervous systems of animals, refer to the article the nervous system . For information on the anatomical structure and details of the functioning of the nervous system of a person, refer to the articles on the human brain and peripheral nervous system .

Content

The Importance of Neuroanatomy as a Science

Studying how a particular part of the nervous system is structurally and functionally organized, what subunits (smaller parts) or structural blocks it consists of, and how these subunits or structural blocks are interconnected, is critical to understanding how this part The nervous system is generally arranged and working. So, for example, a significant part of the information on the structure and functions of the brain that neuroscientists now possess was obtained by applying specific, relatively small in size lesions (“lesions”) or, conversely, electrical stimulation of certain areas or structures of the brain , followed by a study of how this affects the behavior , memory , emotions and other physiological aspects of the life of experimental model animals .

History of Neuroanatomy

The first written historical information about attempts to study the anatomy of the human brain is found in ancient Egyptian papyri, in particular the Edwin Smith papyrus [1] . The next big step in the development of neuroanatomy was made by the ancient Greek physician and philosopher Alkmeon, who for the first time established the fact that it was the brain, and not the heart , which was believed before him to control all the functions of the body and all its vital functions, and that the sensory and sensory organs systems depends on the perception of this sensory information by the brain [2] .

After the discovery of Alkmeon, many ancient Greek scientists, philosophers and doctors contributed to the further development of neuroanatomy. In this series, the contribution of Galen , Herophilus , Razes and Erasistratus is especially worth mentioning. Herophilus and Erasistratus from Alexandria were, apparently, the most influential and authoritative among the early ancient Greek neuroscientists, and studied in detail the structure of the human brain in numerous sections [2] . For many hundreds of years after this, in connection with the categorical prohibition of the Catholic Church on the autopsy of the bodies of the dead, there was no significant progress in neuroanatomy. However, Pope Sixtus IV helped revive the study of the anatomy of the human body, and in particular neuroanatomy, by changing the papal edict on this issue and allowing, with certain restrictions, the autopsy of the bodies of dead people. This led to an explosive increase in the number of studies of human anatomy and, in particular, human neuroanatomy by both scientists and artists of the Renaissance [3] .

In 1664, Thomas Willis , a physician and professor at the University of Oxford, first used the term neurology in his pioneering book Lat. Cerebri anatome . The publication of this book by Willis, as is commonly believed, marks the beginning of a systematic study of human neuroanatomy [4] . In the next little more than 350 years, from Willis to the present day, neuroanatomy has become one of the most rapidly developing sections of anatomy. This led to the publication of a huge number of books, articles, medical documents devoted to various aspects of the study of neuroanatomy, the structure and functioning of the nervous system and brain.

Components

At the tissue level , the nervous system consists of neurons , glial cells, and an extracellular matrix. Both neurons and glial cells come in many different types. Neurons are cells of the nervous system that perform its main function - processing incoming information and generating control signals based on it. In particular, they perceive sensory information from the external environment (coming from the senses), as well as interoceptive and proprioceptive information about the internal state of the body, communicate with each other using electrical signals and chemicals called neurotransmitters , and as a result of all this activity, shape our memories , thoughts , emotions , movement , behavioral acts , and others. Glial cells maintain homeostasis in the nervous system, produce the myelin sheathing axons , and provide hooked housing services, food, and protection of neurons. Some types of glial cells ( astrocytes ) are also able to generate calcium ion gradient waves propagating over long distances in response to electrical or chemical stimulation, and to release specific chemicals, the so-called gliotransmitters, in response to changes in the concentration of calcium ions in the extracellular space. Thus, some types of glial cells also participate in the transmission of information signals. The extracellular matrix provides support and nutrition to brain cells at the molecular level.

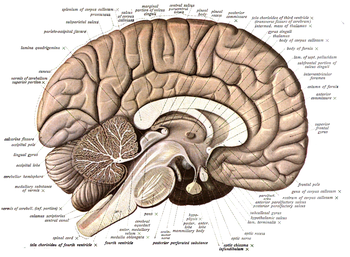

At the level of organs, the nervous system consists of the brain (or periopharyngeal nerve ring , it is also the “central nerve node”), the spinal cord (or the central nerve axis, neuraxis), peripheral nerves and sensory nerve endings (receptors or sensors) located on the ends of the peripheral nerves ) or conjugation with effector organs, such as neuromuscular or neuro-glandular synapse. In turn, the brain or periglottal nerve ring consists of separate anatomical structures, such as the thalamus in the chordates or the mushroom bodies in the fruit fly of Drosophila [5] . The spinal cord or central nerve axis (neuraxis) also consists of separate segments. These various structures and regions of the brain or periopharyngeal nerve ring, in turn, have a modular structure, that is, they consist of smaller substructures, each of which performs certain physiological functions , ensuring the operation of certain nerve paths and paths. For example, the thalamus is critical for the integration of sensory information, and the hippocampus for the formation of memory .

Peripheral nerves are bundles of nerve fibers emanating from the brain and spinal cord (or from the periopharyngeal nerve ring and central nervous axis, respectively), which then branch and innervate all parts and organs of the body many times, and end with either sensitive nerve endings (for afferent nerves ), or by interfacing with cells of the effector (executive) organs, for example, neuromuscular or neuro-glandular synapses. Peripheral nerves are mainly composed of axons of individual neurons, as well as the myelin sheaths and other membranes that cover them, they are separated (electrically isolated) and collected in nerve fibers and bundles of nerve fibers (tracts).

The nervous system of all chordate animals is divided into the central and peripheral nervous system. The central nervous system consists of the brain , cranial nerves , retina and spinal cord . The peripheral nervous system consists of all the other nerves (that is, nerves originating not from the brain, but from the spinal cord) connecting the central nervous system to all other parts of the body. The peripheral nervous system, in turn, is divided into somatic and autonomous (or autonomic) nervous systems. The somatic nervous system consists of afferent neurons that transmit sensory information from the sensitive nerve endings (receptors or sensors) in the sensory organs to the central nervous system, and efferent neurons that transmit motor information to the muscles through the neuromuscular synapse. The autonomic, or autonomic, nervous system, in turn, has two divisions or departments: the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. These two parts of the autonomic nervous system are in constant dynamic equilibrium or balance, and in many respects are functional antagonists of each other. Their dynamic balance or balance is responsible for the regulation of such basic vital functions of the body as the frequency and strength of heart contractions, the tone of blood vessels and other smooth muscle organs, the frequency and depth of respiration, the secretion of saliva and other digestive juices, gastrointestinal motility, body temperature, secretion of hormones, etc. The nerves of the autonomic nervous system, like the nerves of the somatic nervous system, contain afferent and efferent fibers.

Orientation and localization of structures in neuroanatomy

In anatomy in general, and in neuroanatomy in particular, several interconnected sets of topographic terms are traditionally used that describe the mutual spatial location (localization) of anatomical structures with respect to each other and to the body axes, and their spatial (topographic) relationships with each other and with body axes (see article anatomical terminology ). In the case of neuroanatomy, we are talking about the mutual spatial arrangement and spatial relationships of parts of the nervous system, including the brain and spinal cord, peripheral nerves, in relation to each other and to the axes of the body or brain. However, the interpretation of these traditional anatomical terms in relation to the brain and spinal cord, especially in upright animals (humans and higher primates), and therefore in relation to the field of neuroanatomy as a whole, has its own characteristics, sometimes leading to difficulties and ambiguities or misunderstanding, according to compared with other sections of anatomy. The reasons for this will be described below.

The most commonly used pairs of topographic terms in neuroanatomy include:

- Dorsal and ventral . The term “dorsal” with respect to the structures of the brain means “upper”, “located above”, and the term “ventral” with respect to the structures of the brain means “lower”, “located from below”. Etymologically, these terms come, respectively, from the concepts of lat. dorsum - back and ventrum - abdomen, abdominal cavity (in chordates) or abdomen (in arthropods). Thus, initially, these terms meant, respectively, “dorsal” (that is, facing the back, or located closer to the back), and “abdominal” (that is, facing the abdomen, abdominal cavity or abdomen, or located closer to the stomach, abdomen or abdomen). The abdomen (abdominal cavity) or abdomen in most animal species is facing the earth's surface, while the back is facing up. Accordingly, the “dorsal” (dorsal) for most animal species in all cases is synonymous with the word “upper”, “located above”, and “ventral” (abdominal) is a synonym for the word “lower”, “located below”. However, the uprightness of humans and, in part, the uprightness of higher primates confuses the situation. The erectness of humans and higher primates leads to the fact that the ventral (abdominal) aspect of the human body and higher primates is not in front, but from below. The dorsal (dorsal) aspect of the human body and higher primates is located not from above, but from behind. In this sense, the terms “dorsal horns of the spinal cord” (synonym for “posterior horns of the spinal cord”) and “ventral horns of the spinal cord” (synonym for “front horns of the spinal cord”) should be interpreted. The situation with the interpretation of the terms “dorsal” and “ventral” in relation to the head and brain, especially in humans and higher primates, is even more confusing. The abdomen, abdomen or abdominal cavity does not pass directly to the front or lower parts of the head, neither in erectus (humans and higher primates), nor in other animal species. The back or spine also does not go directly to the back or upper part of the head, neither in erectus (humans and higher primates), nor in other animal species. Accordingly, with a literal interpretation, the terms “dorsal” (“dorsal”) and “ventral” (“abdominal”) would be meaningless with respect to the head and brain. To give the terms “dorsal” and “ventral”, in relation to the head and brain, a new meaning, neuroanatomists agreed to consider that the mouth (oral cavity) and the front of the skull are a kind of extension or extension of the abdomen or abdominal cavity, and the posterior-upper the surface of the skull is a kind of extension or extension of the back or spine. Thus, those parts of the human brain and higher primates that are located lower, closer to the base of the skull and to the oral cavity, are called ventral, and those parts of the brain that are located higher, closer to the “roof” of the cranium are commonly called dorsal . This fully coincides with the interpretation of the terms “dorsal” and “ventral” for all parts of the body, including the brain and spinal cord, in other animal species (where these terms also mean “top” and “bottom”, respectively), but do not coincide with the interpretation the same terms “dorsal” and “ventral” for the spinal cord of humans and higher primates (where the same terms mean “posterior” and “anterior”, respectively, due to the upright position of humans and higher primates). To avoid such a difference in interpretations depending on what the terms “dorsal” and “ventral” refer to — the brain of a person and higher primates, or their spinal cord — a number of scientists writing articles on human neuroanatomy and higher primates, they prefer to use not the terms “dorsal” and “ventral” to describe the mutual anatomical arrangement of brain structures, but the terms “cranial” and “oral,” respectively.

- Rostral and caudal . The term "rostral" for almost all types of animals refers to the front, or head, nasal part of the body or any of its anatomical structure, while the term "caudal" for almost all types of animals refers to the back, or tail, of the body or any of its anatomical structure. Etymologically, these terms come from rostrum - nose, and cauda - tail. Однако у человека и высших приматов, в связи с их прямоходячестью и вертикальным положением тела (вертикальным положением оси «голова-хвост», или, в случае человека, у которого нет хвоста, оси «голова-копчик») термины «ростральный» и «каудальный» логически являются синонимами не терминов «передний» и «задний», а терминов «верхний» и «нижний», например, для спинного мозга. Применение этих терминов по отношению к головному мозгу осложняется ещё и тем, что все без исключения позвоночные в период эмбрионального развития образуют изгиб на 90 градусов нервной трубки , так называемую мезэнцефалическую флексуру. Этот изгиб продолжает, в видоизменённой форме, существовать и у взрослого человека или взрослого животного. Именно этот изгиб отделяет передний мозг от ствола мозга и спинного мозга . Благодаря существованию этого изгиба ростральная (верхняя) часть головного мозга эмбриона становится в итоге передней, носовой частью головного мозга взрослого человека или животного, а каудальная (нижняя) часть головного мозга эмбриона становится в итоге задней, «хвостовой» частью головного мозга взрослого человека или животного. Таким образом, получается, что пространственное значение терминов «ростральный» и «каудальный» отличается для головного и для спинного мозга. Оно также отличается для эмбрионов и для взрослых людей и животных, для прямоходячих (человек и высшие приматы) и не-прямоходячих животных. Чтобы избежать этих проблем, рекомендуется пользоваться терминами «верхний» и «нижний», «передний» и «задний» при описании относительного анатомического расположения структур головного и/или спинного мозга, а также положения плоскости рассечения.

- Медиальный , медианный и латеральный . Термин «медиальный» (буквально «срединный») в анатомии означает, что анатомическая структура, о которой идёт речь, находится вблизи (или относительно ближе к) срединной линии или срединной плоскости сечения тела. В случае головного мозга этот термин означает близость к межполушарной срединной плоскости сечения мозга. Термин «медианный» или «центромедианный» означает, что анатомическая структура, о которой идёт речь, располагается точно по срединной линии или срединной плоскости. Напротив, термин «латеральный» (буквально «боковой») означает прямо противоположное — то, что анатомическая структура, о которой идёт речь, находится сбоку от срединной линии или срединной плоскости, на некотором удалении от неё. В отличие от пар терминов «дорсальный/вентральный» и «ростральный/каудальный», термины «медиальный/медианный/латеральный» не меняют своё значение в зависимости от прямоходячести или не-прямоходячести того или иного животного (то есть от естественного положения самой длинной из осей его тела, от положения спины/живота и головы/хвоста по отношению к Земле), или от того, идёт ли речь о головном мозге или о спинном, идёт ли речь о головном мозге взрослого человека или животного, или о головном мозге эмбриона на той стадии развития, в которой у него ещё нет мезэнцефалической флексуры. Поэтому употребление терминов «медиальный/медианный/латеральный», в отличие от вышеупомянутых пар терминов, не сопряжено с какими-либо проблемами или неоднозначностями трактовок.

Важно отметить, что все эти термины (дорсальный/вентральный; ростральный/каудальный; медиальный/медианный/латеральный) являются относительными, а не абсолютными. Так, например, некая латерально расположенная анатомическая структура может быть названа лежащей медиально по отношению к какой-либо структуре, расположенной ещё латеральнее (ещё дальше от срединной плоскости).

Инструменты нейроанатомии

Модельные организмы

See also

- Головной мозг

- Головной мозг человека

- Neurology

- Нейробиология

- Нервная система

- Центральная нервная система

- Периферическая нервная система

Notes

- ↑ Atta, HM Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: The Oldest Known Surgical Treatise (англ.) // American Surgeon : journal. - 1999. - Vol. 65 , no. 12 . — P. 1190—1192 . — PMID 10597074 .

- ↑ 1 2 Rose, F. Cerebral Localization in Antiquity (англ.) // Journal of the History of the Neurosciences : journal. - 2009. - Vol. 18 , no. 3 . — P. 239—247 . — DOI : 10.1080/09647040802025052 .

- ↑ Ginn, SR; Lorusso, L. Brain, Mind, and Body: Interactions with Art in Renaissance Italy (англ.) // Journal of the History of the Neurosciences : journal. - 2008 .-- Vol. 17 , no. 3 . — P. 295—313 . — DOI : 10.1080/09647040701575900 .

- ↑ Neher, A. Christopher Wren, Thomas Willis and the Depiction of the Brain and Nerves (англ.) // Journal of Medical Humanities : journal. - 2009. - Vol. 30 , no. 3 . - P. 191-200 . — DOI : 10.1007/s10912-009-9085-5 .

- ↑ Mushroom Bodies of the Fruit Fly (недоступная ссылка) . Дата обращения 2 ноября 2017. Архивировано 16 июля 2012 года.