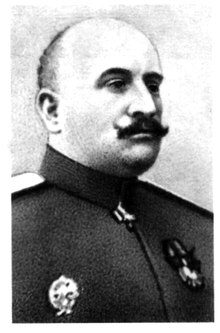

Aleksandr Mikhailovich Krymov ( October 23, 1871 - August 31, 1917 ) - Russian general, participant in the conspiracy of A. I. Guchkov with the goal of a palace coup.

| Krymov Alexander Mikhailovich | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| Date of Birth | October 23, 1871 | |||||||||

| Date of death | August 31, 1917 (aged 45) | |||||||||

| Place of death | Petrograd | |||||||||

| Affiliation | ||||||||||

| Type of army | ||||||||||

| Rank | major general | |||||||||

| Battles / wars | Russian-Japanese war , World War I | |||||||||

| Awards and prizes | ||||||||||

Biography

From the nobles of the Warsaw province . He studied at the Pskov cadet corps . He entered the service on September 1, 1890, in 1892 he graduated from the Pavlovsk Military School . He was released from college as a second lieutenant (August 4, 1892) into the 6th artillery brigade . Lieutenant (August 5, 1895), staff captain (July 19, 1898). In 1902 he graduated from the Nikolaev Academy of the General Staff in the first category. The censored command of the company was serving in the 182nd Grokhovsky Regiment (October 31, 1902 - February 26, 1904).

Member of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 , during which he served in the headquarters of the 4th Siberian Army Corps .

From November 4, 1906, the clerk of the mobilization department of the General Staff , from March 14, 1909 - the mobilization department of the General Directorate of the General Staff (GUGSh), and from September 19, 1910, the head of the department of the General Staff. Since July 15, 1911, the commander of the 1st Argun Regiment of the Transbaikal Cossack Army . Since November 25, 1913, the acting general for assignments under the commander of the troops of the Turkestan military district, General A. V. Samsonov .

World War I

After the outbreak of the First World War, August 18, 1914 General for errands at the headquarters of the 2nd Army, commanded by A.V. Samsonov . On September 7, 1914, the commander of the brigade of the 2nd Kuban Cossack Division. From 03/27/1915 the head of the Ussuri equestrian brigade. He earned the fame of a decisive cavalry chief. On December 18, 1915, the brigade was deployed into a division and Krymov was appointed its commander. In the fall of 1916, the division was transferred to the Romanian front.

“A few weeks later I received clarifications about Krymov’s strange behavior. The grounds for the retreat order were:“ Having lost all confidence in the Romanian army, I decided to withdraw my division to the nearest Russian army corps and join it. ”What a simple solution! It's hard to understand as General Krymov, who had a good reputation, could so flagrantly violate the laws of war, among other things, he left the position without warning, so there was nothing to even try to correct the harm done to them. committed the General Staff with impunity! " (From the memoirs of K.G. Mannerheim).

February coup

Long before the February Revolution, Krymov was close to the Duma opposition to Nicholas II. The historian of Russian Freemasonry Nina Berberova writes [1] :

| We now know that generals Alekseev , Ruzsky , Krymov, Teplov and, perhaps, others, with the help of Guchkov, were consecrated into Freemasons. They immediately joined his "conspiratorial plans." All these people, oddly enough, had high hopes for the regency (under the young prince Alexei) led. Prince Mikhail Alexandrovich , brother of the king. Why he seemed to them a suitable person is not clear. Whether Guchkov spoke about this with Mikhail Alexandrovich himself is not known ... |

In January 1917 Krymov left for Petrograd. According to the memoirs of M. V. Rodzianko Krymov spoke to a group of Duma members, promising support for the army in the coup [2] :

| The mood in the army is such that everyone will gladly welcome the news of the coup. A coup is inevitable and at the front they feel it. If you decide on this extreme measure, then we will support you. Obviously, there are no other means. Everything has been tried both by you and many others, but the harmful influence of the wife is stronger than the honest words spoken to the King. Time must not be wasted. |

On February 11, Krymov returned from Petrograd to Chisinau. After the February Revolution, on March 14, Krymov again left for Petrograd to negotiate with Guchkov. P.N. Wrangel describes Krymov’s return from Petrograd on March 30 [3] :

| General Krymov, having seen Guchkov, M. V. Rodzianko, Tereshchenko and his other political friends, returned significantly encouraged. According to him, the Provisional Government, despite the apparent weakness, was strong enough to take control of the movement. In addition to the general public and a large part of the army, the main support of the Provisional Government should have been, according to General Krymov, Cossacks. |

After the commander of the 3rd cavalry corps, F. A. Keller refused to swear allegiance to the Provisional Government, for which he was fired from the army on April 5, 1917, Krymov was appointed in his place.

Death

During the Kornilovsky speech , L.G. Kornilov sent the 3rd Cavalry Corps on August 25, 1917 (by that time it was in the reserve of the Romanian Front ) and the Native Division to Petrograd. These units were to become the basis of the Separate Petrograd Army, directly subordinated to the Headquarters. August 24, 1917 Krymov was appointed gene. L. G. Kornilov, Commander-in-Chief of a separate Petrograd Army. Krymov was charged with suppressing performances in the capital. The 3rd cavalry corps of Krymov departed by train from Stavka (Mogilev) (from the Nevel-Novosokolniki area, where the corps was transferred in July 1917) in the direction of Petrograd.

On August 30, on behalf of Kerensky, Krymov was visited by the head of the cabinet of the Minister of War, Colonel Samarin, formerly the chief of staff of the Ussuri equestrian division of Krymov, with a proposal to go to Petrograd for negotiations. Krymov decided to go. He arrived at Kerensky, where he presented his explanations of the events and after Kerensky’s offer of surrender, he realized that he was in a trap arranged by Kerensky to entice him and, having separated him from the units loyal to him, forcibly isolate him. Having learned the real essence of Kerensky’s plans, realizing his position as an actual prisoner, as well as the impossibility of changing anything, Krymov preferred death to humiliating interrogations and arrest. Leaving Kerensky’s office, he shot himself.

Memories of Krymov

Skin

General A. G. Shkuro , a well-known participant in the White Movement, recalls Krymov: [4]

| Here I am somewhat distracted by describing General Krymov, with whom I often had to work. He, rude in appearance, harsh in words, delivering his subordinates without choosing expressions, bullying for any reason with his superiors, enjoyed, despite all this, the unlimited respect and ardent love of all his subordinates, from senior officer to junior Cossack. Behind him, at his first word - everything is into fire and into water. He was a man of iron will, indomitable energy, and undaunted personal courage. He quickly understood the most complicated military situation and made bold but invariably successful decisions; he studied his subordinates well and was able to use their fighting qualities and even their very shortcomings. So, knowing the Cossacks' tendency to keep horses near themselves, so that in case of failure they would hastily change their location, Krymov kept the horse guides about 50 miles from the battlefield, thanks to which his Cossacks held on foot stronger than the staunch infantry. Knowing the location of the fire, he, with his Transbaikal people, nature hunters, used this method of fighting an advancing enemy: he occupied the mountain peaks with separate platoons of Cossacks, who arranged there in their own way and beat to choose from. No artillery fire, no Bavarian attacks could smoke from the mountain crevices of the Cossacks who had settled in them. I did not work long with Krymov, but I learned many valuable lessons and a fond memory of this valiant soldier, this honest man who could not put up with the traitor Kerensky and survive the shame of Russia. Eternal memory to him! |

Mannerheim

The most critical situation was on the left flank, where the equestrian division of Major General Krymov, acting as a link between the Vranza group and the 3rd Romanian army corps, defended the central section of the Magura mountain range (the highest point is 1001 meters above sea level). In the east from the mountain was visible the city of Fokshany and the surrounding plain, which seemed limitless.

Late in the evening of January 2, 1917, I received stunning news. Prior to this, during the day we tried unsuccessfully to contact the field units of Krymov, and finally it turned out that the general with his entire division had withdrawn without warning the neighboring formations. Neither I nor the headquarters of the Romanian army had free forces to take this position, and the Germans were not slow to capture the site that Krymov controlled and to begin shelling Fokshan. General Averescu with his headquarters had to leave. When, after a few days, our units regrouped to retaliate, the ridge was already very strong, and it took a lot more troops to return this section.

A few weeks later I received clarifications about Krymov’s strange behavior. The basis for the withdrawal order was the following: "Having lost all confidence in the Romanian army, I decided to withdraw my division to the nearest Russian army corps and join it." What a simple solution! It is difficult to understand how General Krymov, who had a good reputation, could so crudely violate the laws of war. Among other things, he left the position without warning, so there was nothing even to try to correct the harm done to him. And such a crime, this officer of the General Staff committed with complete impunity! For a month, Vranza’s group defended approaches to the Fokshans, after which it was taken for rest and replenishment. The order for the 12th Cavalry Division stated that it should be redeployed to Bessarabia , or rather, in the vicinity of Chisinau . I could not help but regret that I had to leave the command of the troops in the Transylvanian Alps .

- Karl Gustav Mannerheim , Memoirs.

Rewards

- Order of St. Stanislav 3rd Art. (1898)

- Order of St. Vladimir 4th art. with swords (1905)

- Order of St. Anne 4th Art. (1905)

- Order of St. Anne, 3rd art. with swords and bow (1905),

- Order of St. Stanislav, 2nd art. with swords (1905)

- Order of St. Anne, 2nd century with swords (1906),

- Order of St. Vladimir 3rd art. (04/19/1911).

- St. George's weapons (VP 08.11.1914).

- Order of St. George 4th Art. (VP 06/26/1916).

Notes

- ↑ Nina Berberova. People and lodges

- ↑ Multatuli, P.V. The Lord bless my decision ... Emperor Nicholas II at the head of the army and conspiracy of the generals . - SPb. : Power: Satis, 2002. - ISBN 978-5-7373-0171-2 .

- ↑ From the memoirs of P.N. Wrangel

- ↑ A. G. Shkuro Notes of the White Partisan - M .: ACT Publishing House LLC: Transitkniga LLC, 2004. - 540 p. - (Military Historical Library). The circulation of 5,000 copies. ISBN 5-17-025710-4 (LLC Publishing House ACT) ISBN 5-9578-1185-8 (LLC Transitkniga)

Literature

- Zalessky K. A. Who was who in the First World War. - M .: AST ; Astrel, 2003 .-- 896 p. - 5,000 copies. - ISBN 5-17-019670-9 (ACT); ISBN 5-271-06895-1 (Astrel).

- A. G. Shkuro Notes of the White Partisan - M.: Publishing House ACT LLC: Transitkniga LLC, 2004. - 540 p.

Links

- Krymov, Alexander Mikhailovich . // Project "Russian Army in the Great War".

- Biography of A. Krymov on the Chronos website

- A.I. Denikin Essays on Russian Troubles. Chapter vi