“Our Revolution” is the book of Leo Trotsky , published in 1906 under the pseudonym N. Trotsky and which is a collection of articles written in 1904-1906. The most important and famous was the final article "Results and Prospects" , which caused a resonance among the revolutionaries of the early XX century; the article claimed that the Russian Empire was a backward country of the “second echelon” of capitalism , and concluded that the Russian bourgeoisie was weakly comprehensively dependent on the state and autocrat . In the book, Trotsky as a whole completed the formation of his concept of “permanent revolution” and the “law of uneven and combined development,” based on the works of A. Parvus , K. Kautsky and P. Milyukov ; according to Trotsky's ideas, it was the proletariat , which, unlike the commercial and industrial class, which could paralyze the economy of the Russian Empire, was destined to play a key role in the future revolution , which should begin on a national basis, unfold on an international basis and end on a worldwide basis. Thus, the Russian state was assigned the role of a “detonator” of the revolutionary upsurge in the West, capable of uniting Russia and Europe .

| Our revolution | |

|---|---|

| Our revolution | |

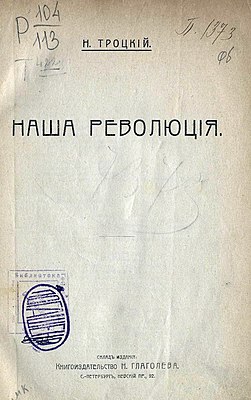

The title page of the 1906 edition | |

| Genre | journalism, politics |

| Author | Trotsky L. D. |

| Original language | Russian |

| Date of writing | 1904-1906 |

| Date of first publication | 1906 |

| Publishing house | Book publishing by N. Glagolev (1906) |

Trotsky’s views, which in those years were a little to the left of V. Lenin’s political position, being significantly distorted by later critics, began to be perceived in Soviet Russia in the 1920s and 1930s as Trotsky’s main " heresy " against Leninism . The book and the final article have been translated into many languages. and repeatedly reprinted; in 1922, Trotsky's book “1905” was published in the USSR, containing fragments of “Our Revolution” .

Description and History

After the arrest on December 3, 1905, in the prison cell in Kresty , the head of the St. Petersburg Council of Workers' Deputies Lev Trotsky was “greatly impressed” by the “surprisingly important” role that the workers of the Russian Empire played during the 1905 Revolution [1] [2] [3] [4] , - basically completed the formation of his concept of “permanent revolution” [5] . During his work on the theory, Trotsky’s cell, according to his cellmates, “turned into some kind of library” [6] [7] . After the trial and escape from exile, Trotsky set forth his views in a number of articles and speeches - only the “study of land rent” was lost and never saw the light of day [8] . In 1906, these works were collected in a book that received the title “Our Revolution”. The main articles included in the collection included: “Until January 9,” “Capital in Opposition,” “How the State Duma was Done, ” and “Open Letter to prof. Milyukov ”and“ Mr. P. Struve in Politics ”(previously published under the pseudonym N. Takhotsky [8] ). Of particular importance, in the sense of the final formation of the author’s concept of permanent revolution, was the final article of the book, which had the heading “Results and Prospects” [9] [10] - its title was a reference to a similarly entitled article by Parvus [11] [12] ; it was Trotsky’s final article that later became the subject of “bitter controversy” ( eng. bitter controversy ) [13] [14] .

After the book was published, the police of Tsarist Russia confiscated the print run: only a few copies of the work of the revolutionary reached the readers [15] [16] . Moreover, even in the pamphlet “Until January 9,” written before the events of Bloody Sunday , Trotsky came to the conclusion that “only the proletariat can save Russia” and predicted the beginning of an “All-Russian armed uprising” in the coming months or even weeks [17] (see Revolution of 1905 ).

Key Points and Their Criticism

The Backwardness of the Russian Empire

The authors of a four-volume biography of Trotsky, Yuri Felshtinsky and George Chernyavsky, believed that one of the most important starting points of the new concept of the revolutionary process developed by Trotsky and which became an integral part of Our Revolution was the fact that the Russian Empire was a country in the 19th and early 20th centuries “ the second echelon ”of capitalism — at the same time, it constantly strove to catch up with the more developed ( Western European ) countries [9] [18] [19] . Autocratic Russia, according to Trotsky, was not able to "make an innovative breakthrough": the author tried in the most general terms to trace the tendency to lag behind Kievan Rus to the " great reforms " and the abolition of serfdom in the middle of the XIX century; the latter was intended to facilitate the formation of the armed forces of the empire and the collection of taxes, while not creating real prospects for the liberated peasants themselves [20] . Trotsky, according to Felshtinsky and Chernyavsky, showed that the borrowing of foreign technical, economic and other achievements did not lead to intensive economic development in the Russian Empire: in other words, the desire to “catch up” with the tradition did not lead to a real achievement of the Western standard of living and technical development [9] . But the lag of the Russian Empire itself was not total — which distinguished it from traditional Asian societies like India and China at the beginning of the 20th century, which did not have a common border with Europe [21] .

The “catching up trend” - being the result of “imposing from above” (from the sovereign rulers), and not from below (at the initiative of public organizations that in those years sought primarily economic and managerial independence) –– was not able to lead to the creation of such a “fundamental the Institute of Confrontation with the Middle Ages ”, which were European cities, which were distinguished by an increasingly intense independent economic and political life [9] . While the cities of Russia were only administrative, military and tax centers [22] [23] - fortresses [24] .

| When in the second half of the 19th century the extensive development of the capitalist industry began in our country, it did not catch the craft of the city, but mainly rural handicraft [24] . |

Trotsky, according to Felshtinsky and Chernyavsky, drew attention to the fact that the Russian Empire and its predecessors, in accordance with Marxist ideas [25] , developed as a superstructure on a slowly evolving primitive society : the state improved and strengthened, subject to the instinct of self-preservation [26] and turning into an increasingly independent (relative to society) and powerful structure. According to Trotsky, this happened under external pressure: primarily in the form of the Tatar-Mongolian , Polish-Lithuanian and Swedish invasions . Surviving the state under such pressure required "the greatest exertion of forces," therefore, it absorbed a disproportionate share of the material goods and resources produced by society, and also actively borrowed money in the West [27] [28] . The state also simultaneously needed a powerful apparatus of violence and control - a rigid hierarchical (military) structure [9] , which, according to Trotsky’s calculations, absorbed more than half of the empire’s state budget and bureaucratized the country's life. The main financial burden fell on the peasants, whose economic life, already complicated by the “harsh climate and vast expanses” [24] , was thus completely undermined [29] .

| The [Russian] state was not formed under the influence of impulses emanating from Russian society itself, but under the hostile pressure of strong European powers [30] . |

Unlike the West, in the Russian Empire, the state itself, in the understanding of Trotsky, gave rise to the estates (this idea was previously expressed by Milyukov [24] [23] ) and laid the foundation for modern industry - primarily military [26] . From this, Trotsky concluded that the Russian bourgeois class , which led an almost parasitic existence, is objectively weak and entirely dependent on autocratic power: it is unable to become an independent social entity - the carrier of an economic and political alternative to autocracy (as happened in Western Europe ) [31] [32] . In other words, the commercial and industrial estate in the empire was doomed to comprehensive dependence on the state, that is, ultimately on the autocrat . From this followed Trotsky’s conclusion that under Russian conditions a purely bourgeois revolution capable of overthrowing tsarism and “cleansing the country of semi-feudal survivals” [30] was impossible [9] [33] . According to the analysis of the future People’s Commissar , Russian Tsarism was an intermediate form between European absolutism and Asian despotism [34] . It was these features of both Russian history and the class structure of Russian society at the beginning of the 20th century that meant that the proletariat of the Russian Empire, concentrated on large advanced enterprises [35] implanted by foreign entrepreneurs [36] , was destined, according to Trotsky, to play a key role in the revolution [37] , inevitable due to internal conflicts of an artificial system in which the middle class was absent [38] .

| Even Russian thought and science seem to be a product of the state [24] . |

At the same time, the visible power of the empire - consisting of a set of attributes typical of the Western Great Powers , and allowing the Russian tsars to regularly intervene militarily in European politics - was only an illusion of security from both external and internal threats [28] . The small number of the Russian proletariat was not, according to Trotsky, a significant obstacle to the revolutionary seizure of power by the workers : in particular because it was the workers who ensured the functioning of the country's railway network , without which its economy as a whole could not function [39] (“a thousand striking railway workers politically more effective than a million peasants scattered throughout the country ” [40] ). In other words, it was even easier for the Russian proletarians to come to power than their Western European counterparts [41] [42] ; The "embryo" of such a workers' government was the St. Petersburg Council itself, which was headed by Trotsky [1] .

In the book, the future drug trade war also touched upon the military aspects of the impending revolution: already in 1906, Trotsky opposed guerrilla warfare tactics, being a supporter of the mass arming of the population (especially workers sharing the ideas of socialism ) and the building of a regular army capable of defeating the bourgeois enemy in open battle [43 ] (see Tsaritsyno conflict ):

| To arm the revolution means, first of all, in our country to arm the workers. |

Professor David Davis, in his review of the English translation of 1905, wrote about four of Trotsky’s “clear elaboration ideas” that stemmed from his 1905 experience and which together created the revolutionary his “distinctive position” ( Engl. distinctive position ) in the history of Russian revolutionary thought. To these ideas of the future Commissar, Davis attributed: a penetrating understanding of the features of Russia as a state and the fact that the revolution in the Russian Empire will not go in accordance with Western precedents ; the recognition that the course of history is determined not so much by the rational calculation of people as by their readiness for action; awareness of the importance of military power in the revolution and the decisive role of the army in summing up the final outcome of the struggle for power; understanding of the significance of the Council of Workers' Deputies as a revolutionary institution [44] . At the same time, the drawback of Trotsky’s key thesis about the possibility of a permanent revolution was ultimately the author’s unwillingness to answer questions that bothered other participants in the events of 1905: the connection between the Social Democratic Party and the Soviets, the relationship between the proletariat and the peasantry, and the connection between the Russian revolution and the European the proletariat, as well as between the instinct of the masses and the realistic wisdom of individuals; all these points turned out to be “not so smooth,” as Trotsky assumed at that time [45] .

Law of Uneven and Combined Development

Felshtinsky and Chernyavsky noted that much later - in the late 1920s and early 1930s - Trotsky more clearly formulated those general provisions that underlie his reasoning about the premises of a permanent revolution; he called them “the law of uneven and combined development” [46] [47] [48] [10] [49] . In fact, the provisions of the law at that time were already contained in Trotsky's publications , which were published at the beginning of the century in the framework of the book “Our Revolution” [9] [50] - the historian Georg Lichtheim also agreed with this statement, who noted that more mature formulations from the book “ Permanent Revolution ” and “ Stalin ” essentially do not disagree with the original thesis [51] [52] [53] [54] , but only are its protection against subsequent criticism [55] .

The law of uneven and combined development, in Trotsky's formulation, denied the existence of a mandatory direct link between the development of productive forces (see Marxist political economy ) and the political role of the proletariat in a particular country, at one stage or another of its development [56] : in particular, despite the tenfold superiority of the United States over the Russian Empire in terms of industrial production at the beginning of the 20th century, the political role of the Russian proletariat was, in Trotsky's opinion, incomparably higher than that of the American [57] [58] .

According to professors Howard and King, Trotsky’s ideas from “Our Revolution” - “the most radical of the works of Russian revolutionary socialism” [59] - denied the idea expressed earlier by Karl Marx and developed in the writings of George Plekhanov and Vladimir Lenin - “a country more industrially developed, shows a less developed country only a picture of its own future ”- and, thus, the revolutionary ideas of the future Commissar changed the idea of the very path of Westernization of Russia. Trotsky formulated the principles of political economy , thanks to which, deeper than any other theorist, he came closer to understanding both the structure and the contradictions of the tsarist modernization of the Russian Empire - and, consequently, the nature of the Russian revolutionary process. Trotsky, according to Howard and King, argued that, as in the past Russia did not follow the traces of the developed West, its future path was different [60] : in particular, the democratic way of building socialism on the territory of the empire was excluded by the revolutionary [61] .

Russia and Europe

An integral part of Trotsky's reasoning was the conclusion of both the necessity and the inevitability of a global revolution [9] . The section "Europe and the Revolution" was final in the article "Results and Prospects" and, according to Felshtinsky and Chernyavsky, was considered by the author as the most significant. It stated that the Russian proletariat - even if it had succeeded in coming to power due to the temporary conjuncture of the bourgeois revolution - would inevitably face hostility from the world reaction , which was interested, among other things, in paying off royal debts [35] [62] , and in the safety of their capital [63] ; at the same time, after the start of the revolution, Russian workers could count on the support of the world proletariat. Trotsky assumed that if proletarian power in Russia turned out to be “left to its own devices”, then, as in any other backward country, it would inevitably be destroyed by counter-revolution . Таким образом, пролетариату «ничего другого не останется, как связать судьбу своего политического господства и, следовательно, судьбу всей российской революции с судьбой социалистической революции в Европе [64] » [65] [66] . Троцкий полагал, что западноевропейские рабочие примут сторону российских товарищей при попытке международной буржуазии сокрушить русскую революцию [35] [67] ; он считал пролетариат европейских стран более надёжным союзником, чем российская буржуазия или крестьянство империи [68] ; аграрная проблема империи способствовала подготовке революции, однако после осуществления революционных преобразований становилась препятствием [69] .

Фельштинский и Чернявский отмечали, что создатель концепции не вдавался в детали, полагая, что конкретные пути превращения российской революции в международную — точно так же, как и конкретные сроки, — предсказать невозможно. Читателям лишь давалось понять, что перманентная революция — вопрос не столетий, а сравнительно близкой перспективы. Для того чтобы «оградить себя от упреков в маниловщине », Троцкий многократно подчёркивал условность приведённых им схем: их зависимость от конкретных исторических событий [70] [71] [72] . Сущность же концепции перманентной революции, по мнению Фельштинского и Чернявского, состояла в том, что социалистическая революция начнётся на национальной почве, «развернётся» на интернациональной и завершится на общемировой [73] [74] [75] [35] . Последствия же революции только в России, без распространения на развитые страны, были предсказаны Троцким как «уничтожение» или « эрозия », по причине примитивности экономики, культуры и социума [76] [67] [77] . Профессор Николай Васецкий в 1990 году сформулировал данный принцип как «либо всё, либо ничего» [78] [79] .

| Восточная революция заражает западный пролетариат революционным идеализмом и рождает в нём желание заговорить с врагом «по-русски» [80] |

Израильский историк Шмуэль Галай, анализируя проблемы, с которыми столкнулась марксистская теория в начале XX века, отмечал, что Троцкий (в отличие от Владимира Ленина ) сумел дать более теоретический ответ на события 1905 года: в противоречии с марксистской мыслью своего времени глава Санкт-Петербургского совета пришёл к выводу, что революционный потенциал пролетариата определяется не его бедностью или численностью, а способностью «парализовать капиталистическую экономику». Из данного положения Троцкий, собственно, и делал вывод о возможности социалистической революции в отсталых государствах с малочисленным рабочим классом [81] .

Профессор русской истории и директор Института Восточноевропейских исследований Университета Амстердама Бруно Наарден отмечал, что Троцкий говорил о перманентной революции как о явлении, способном объединить Россию и Европу. В начале XX века данный тезис не был нов, поскольку восходил своими корнями к подобной идее, высказанной ещё Карлом Марксом и Фридрихом Энгельсом , с которой к тому моменту уже «забавлялись» ( англ. toyed ) западноевропейские социалисты [82] . Российский экономист, доктор экономических наук Егор Гайдар считал, что в книге Троцкого была наиболее ярко выражена линия, получившая широкое распространение в российском обществе тех лет и заключавшаяся в возможности для русской революции стать «детонатором» для революционного подъёма на Западе: после чего «социалистическая Европа», в свою очередь, поможет построить социализм и на территории Российской империи (в рамках единых «Соединённых Штатов Европы» [83] ). По версии Гайдара, данная цепочка рассуждений позволяла «затолкать» российский социально-экономический кризис в «узкую логику действий радикальной партии » — давала возможность совместить « светскую религию и политическую практику» [84] [85] [41] .

| Нельзя сомневаться и в том, что социалистическая революция на Западе позволит нам непосредственно и прямо превратить временное господство рабочего класса в социалистическую диктатуру [86] . |

Профессор обращал внимание на то, что в «Нашей революции» Троцкий наделяет некоторые части света «эксклюзивной исторической миссией»: прогрессивная Европа для Троцкого является синонимом цивилизации, в то время как весь остальной мир представляет собой разные степени варварства. Иначе говоря, зависимость России от западного развития — как в прошлом и настоящем, так и в будущем — виделась Троцкому «непреодолимой» ( англ. adamant ) [87] . По мнению профессора Ричарда Стайтса , «высокоинтеллектуальное партнёрство» Троцкого с Парвусом породило теорию, которая российскими рабочими того времени воспринималась, скорее всего, наподобие карго-культа, which already in those years was fixed among the inhabitants of the islands of the Pacific Ocean: some external force will come from abroad to “give” the land and other benefits of civilization [88] .

Original look

Professor Orest Martyshin , speaking of the article “Results and Prospects” as the first source in which Trotsky clearly set out his ideas about the permanent revolution, noted that the author “willingly” supported Alexander Parvus ’s judgment [89] that if social democracy If he leads the future Russian revolution, it would be reasonable if it forms a new government: as a result, according to Trotsky, the bourgeois revolution will almost immediately turn into a socialist one. Martyshin argued that it was this idea that became known as the theory of permanent revolution and that this concept was an attempt to “force events”, thus avoiding two revolutions, separated in time, with the stage of capitalism between them [90] ; in other words, a bourgeois republic was impossible on the territory of backward Russia [69] . Professor Jan Thatcher, discussing in his biography of Trotsky his work “Our Revolution” and “1905”, argued that, despite the fact that a number of elements of the revolutionary concept were already known by 1906 from the works of Parvus, Kautsky , Milyukov [91] , as well as a number of socialist revolutionaries [92] [93] (including Mikhail Gotz [94] [95] ), their synthesis was original [96] [97] [98] . In other words, using the same prerequisites as Parvus, Trotsky was able to create a theory of permanent revolution, different from the concepts of other authors of the early XX century [99] [100] [101] . Professor Perry Anderson considered “Results and Prospects” (Results and Prospects) as the first strategic political analysis of a scientific nature in the history of Marxism [102] .

Trotsky’s biographer Isaac Deutscher , who believed that the events in Russia in 1917 confirmed the forecasts of Trotsky [103] [104] , in his trilogy on the life of a revolutionary , spoke of the article “Results and Prospects” as a work in which the author gave “complete, an almost mathematically concise statement of the theory of “permanent revolution” ”(“ reached the peak of its development ” [105] ): Trotsky analyzed recent key events in the perspective of the“ eternal currents ”of Russian history and determined the place of the Russian revolution in the world. Deutscher also believed that Trotsky unambiguously contrasted his vision of the future revolution with the generally accepted views of the Marxists of his time, who believed that the "old capitalist countries" had already prepared the ground for revolution, and who expected the "victory of socialism" first in the West (while in the countries of the East only the bourgeoisie will come to power): the work of Trotsky to reframe or even radically revised the prospects of the socialist revolution as such - which has not been done since the days of " the Communist m nifesta "in 1847 [106] . Moreover, only Trotsky’s “aversion” to text analysis, according to Deutscher, prevented the revolutionary from “clogging up” his book with “useful” quotes from the writings of the founders of Marxism [40] . Deutscher also added that “Trotsky could not imagine for a minute that the Russian revolution would survive for decades in isolation ” [71] : the revolutionary “did not occur” that the proletarian party would be able to rule a vast country for a long time against the will of the peasant majority [ 107] .

Professor of the University of California at Los Angeles and former President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences drew attention to the fact that, asserting in the book about the need for a global revolution, Trotsky essentially reformulated the thesis of Marx and Engels from their work “ German Ideology ” written as early as 1847, but published only in 1932 in the USSR . The idea of the founders of Marxism was that in the absence of a highly developed society, the revolution will “only spread poverty and the struggle for the most necessary will start again” ( English only poverty would be distributed and the struggle for the necessities would start again ) [76] [ 109] .

Trotsky never denied that the material conditions in Russia were not sufficiently developed to allow the [socialist] revolution to take place. But he argued that this did not undermine the very possibility of starting it [110] . |

Trotsky never denied that the material conditions in Russia were insufficiently mature to allow the consummation of such a revolution. But he did argue that this did not undermine the ability to begin it. |

Impact

After the publication of Our Revolution, Trotsky “gained fame” in the circles of socialist theorists and practitioners, but most of them, according to Felshtinsky and Chernyavsky, reacted sharply to the concept or, at least, with suspicion [73] . At the same time, the conclusion about the possibility of avoiding the long capitalist stage significantly differed from Trotsky's position from the opinion of Parvus [111] . Trotsky’s views were also a little to the left of Lenin’s political position in those years - in particular, on the question of the role of the peasantry in the future revolution [112] [113] [114] [115] , to which Trotsky assigned the role of a “younger partner” under the dictatorship of the proletariat [116 ] [117] [118] [119] ; later Joseph Stalin “exaggerated” ( English magnified out of all proportion ) [120] or “falsified” [121] this discrepancy, making the permanent revolution the main “ heresy ” of Trotsky against Leninism [122] [123] [124] [125 ] [126] [127] [128] (see. Intraparty struggle in the CPSU (B.) In the 1920s ).

Moreover, in 1905, Rosa Luxemburg , Kautsky and Lenin referred to the “permanent revolution” in their works [129] [130] : Lenin again returned to the ideas of the permanent revolution during the First World War [131] . The Mensheviks Alexander Martynov , Julius Martov , Pavel Axelrod and Fedor Dan [132] also discussed Trotsky’s concept, although they gradually cooled down, referring to the impossibility of the seizure of power by the Russian workers themselves (“they considered the next short outline of“ Trotskyism “an empty dream” [15] [133] [134] ). In particular, back in March 1905, Martynov published in Iskra a series of articles under the general title Revolutionary Prospects [135] [136] [137] , where he defended the thesis of the existence of urban bourgeois democracy in Russia, which, in his opinion , there were “certain revolutionary potencies” [138] . Moreover, in the last decade of April 1905 [139] , at a conference in Geneva, the Menshevik faction adopted a resolution that allowed the very possibility of a socialist revolution in the Russian Empire if the Russian revolution could then be transferred to the developed countries of Western Europe [68] , and through the year in March 1906, the Mensheviks published their platform, which contained echoes of the Parvus – Trotsky theory [140] .

As a result, the book Our Revolution, in which the author foresaw the proletarian revolution in Russia [141] [142] [101] , not only became a new stage in Trotsky’s political thought, but also led to his isolation in the social democratic movement of the beginning of the 20th century [143] - he became "a stranger among his own" [15] . Moreover, historical data collected already at the end of the 20th - beginning of the 21st centuries confirmed the general fidelity of the analysis of the Trotsky economy of the Russian Empire in the last years of its existence [144] [145] [146] .

Editions

Trotsky's book was first legally published [16] in the book publishing house of N. M. Glagolev, editor of the newspaper Den; perhaps the publisher was Nikolai Matveyevich Glagolev (b. 1880) - editor of the journal “Herald of Aeronautics”, published at the beginning of the 20th century in St. Petersburg [147] . By the middle of the 20th century, the original publication had become a “bibliographic rarity” [14] - in particular, in 1990, Professor Nikolai Vasetsky , while preparing Trotsky’s first reprint of the USSR in the late 1920s, “failed to find” a pre-revolutionary publication [148] :

- Trotsky N. Our revolution . - SPb. : book publishing of N. Glagolev, type. "North", 1906. - 286 p.

Some of the articles collected in the book came out in the form of separate brochures before 1906:

- Trotsky N. Constitution of the Liberated . - SPb. : Type of. Partnership "Public benefit", RSDLP , 1906. - 19 p.

- Trotsky N. Until the ninth of January / N. Trotsky; with foreword Parvusa ; RSDLP . - Geneva: Type. Party, RSDLP , 1905. - XIV, 64 p.

- Trotsky N. Foreword (The role of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie in Germany in 1848) // Speech before a jury / F. Lassalle . - SPb. : “The Hammer”, 1905. - 95 p.

After October 1917, the article “Results and Prospects”, which is sometimes mistakenly considered to have been published earlier than the book itself [149] , was “reliably” [14] reprinted as a separate brochure, and also, by the end of the year, was published in Russian in Berlin under the title “Prospects for the Russian Revolution” [51] . The last chapter and the last two sentences of the preceding chapter, which predicted the European socialist revolution as a result of the war, were excluded from the German publication “ out of respect ” for censorship during the First World War [150] .

- Trotsky L. Prospects of the Russian Revolution. - Berlin: Ed. t.V. I.P. Ladyzhnikova, 1917 .-- 84 p. - (Socio-Political Library, 3).

In 1919, the article “Results and Prospects” was published in Soviet Russia as a separate publication [148] , and became widely known [151] :

- Trotsky L. D. Results and prospects. The driving forces of the revolution. - M .: "Soviet World", 1919. - 86 p.

In the introduction to this pamphlet, Trotsky himself noted [70] that:

| With regard to the assessment of the internal forces of the revolution and its prospects, the author [in 1906] did not adhere to either of the main trends in the Russian labor movement. The point of view advocated by the author can be schematically formulated as follows. Having begun as a bourgeois in its immediate tasks, the revolution will soon unleash powerful class contradictions and lead to victory, only by transferring power to the only class capable of standing at the head of the oppressed masses, that is, the proletariat. Having risen to power, the proletariat will not only not want to, but will not be able to limit itself to a bourgeois-democratic program. He will be able to bring the revolution to the end only if the Russian revolution passes into the revolution of the European proletariat [152] . |

In 1922, Trotsky's book “1905” was published in Moscow, composed of two previously published texts by the author about the events of 1905: “Our Revolution” and the German-language book “Rußland in der Revolution” [153] , published in Dresden in 1909 [154] [36] . As a result of this, the book “1905” is sometimes dated to 1909, and the Moscow edition of 1922 is considered a reprint [155] [156] [157] [158] :

- Trotsky L.D. 1905 . - M .: State Publishing House, 1922 .-- 427 p.

Translations

In 1918, in New York , an abridged English translation was published by Moses Olgin of the entire book of Trotsky from 1906, entitled "Our Revolution" [51] :

- Trotsky L. Our Revolution: Essays on Working-Class and International Revolution, 1904-1917 / transl. by MJ Olgin . - New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1918 .-- 220 p.

In this version, which included a number of biographies and explanations, the article “Results and Prospects” - “Prospects of a Labor Dictatorship (results and prospects)” - appeared almost entirely: proposals from the penultimate chapter and most of the last chapter omitted in the Berlin edition , became available to English-speaking readers [150] [13] [159] . In English-language sources, several options are used to translate the title of the article: “Itogi i perspektivy”, “Results and prospects”, as well as the version published in Moscow in 1921, “A review and some perspectives” [160] [161] .

In 1909, Trotsky's German-language book Rußland in der Revolution was published in Dresden , which was partly a translation of Our Revolution [51] - the text of the articles in the translation was substantially adapted by the author for non-Russian-speaking readers [162] :

- Trotzki L. Rußland in der Revolution . - Dresden: Buch Druck und Verlag von Kaden & Comp., 1909. - 318 p.

Already in 1919, Trotsky's book was translated into Yiddish [163] ; By 1989, the “Results and Prospects” part was published in Arabic (1965), Chinese (1966, reprinted in 1984), French (1968, reprinted in 1969 and 1974), Dutch (1971), Farsi (1976), Italian (1976) ), Japanese (1961, reprinted in 1967), Serbo-Croatian (1971), Portuguese (1973), Spanish (1971), Swedish (1972) and Turkish (1976) [164] .

Text

- In Russian

- Until January 9 (first article of the book)

- Capital in opposition (second article)

- Constitution of the “Liberated” (third article)

- How did the State Duma (fourth article)

- Open letter to Professor P. N. Milyukov (fifth article)

- October strike (sixth article)

- Mr. Peter Struve in Politics (eighth article)

- Results and prospects (final article of the book)

- In English

- Leon Trotsky "Our Revolution" (1918 book)

- Leon Trotsky "1905" (book "1905")

- In German

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 Schurer, 1961 , p. 466.

- ↑ Knei-Paz, 1978 , pp. 28-29, 176.

- ↑ Tyutyukin, 2002 , p. 140.

- ↑ Howard, King, 1989 , p. 230.

- ↑ Felshtinsky, Chernyavsky, 2012 , p. [87] - [88].

- ↑ Emelyanov, 2003 , p. [132] - [133].

- ↑ Deutscher, 2006 , p. 158.

- ↑ 1 2 Deutscher, 2006 , p. 160.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Felshtinsky, Chernyavsky, 2012 , p. [88].

- ↑ 1 2 Daniels, 2016 .

- ↑ Carr, 1951 , pp. 58, 61.

- ↑ Parvus, 1905 .

- ↑ 1 2 Skilling, 1961 , p. ten.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Deutscher, 2006 , p. 161.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Deutscher, 2006 , p. 174.

- ↑ 1 2 Tyutyukin, Shelokhaev, 1996 , p. 73.

- ↑ Tyutyukin, 2002 , p. 112.

- ↑ Mendel, 1961 , pp. 104-117.

- ↑ Straus, 1998 , pp. 11-12.

- ↑ Knei-Paz, 1978 , pp. 67-68.

- ↑ Knei-Paz, 1978 , pp. 65-66.

- ↑ Knei-Paz, 1978 , p. 78.

- ↑ 1 2 Neumann, 2016 , p. 75.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Deutscher, 2006 , p. 163.

- ↑ Thatcher, 1991 , p. 235.

- ↑ 1 2 Knei-Paz, 1978 , p. 66.

- ↑ Thatcher, 2005 , pp. 36-37.

- ↑ 1 2 Knei-Paz, 1978 , p. 72.

- ↑ Knei-Paz, 1978 , p. 67.

- ↑ 1 2 Deutscher, 2006 , p. 162.

- ↑ Knei-Paz, 1978 , pp. 68–69, 82.

- ↑ Brahm, 1963 , s. 537.

- ↑ Treadgold, 1973 , p. 233.

- ↑ Knei-Paz, 1978 , p. 70.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Thatcher, 2005 , p. 37.

- ↑ 1 2 Löwy, 2010 , p. 51.

- ↑ Thatcher, 2005 , p. 36.

- ↑ Knei-Paz, 1978 , pp. 70, 83.

- ↑ Knei-Paz, 1978 , pp. 85-86.

- ↑ 1 2 Deutscher, 2006 , p. 168.

- ↑ 1 2 Berend, 2016 , p. 130.

- ↑ Wistrich, 1982 , pp. 51, 58.

- ↑ Nelson, 1988 , pp. 49-51.

- ↑ Davies, 1973 , p. 817.

- ↑ Davies, 1973 , p. 818.

- ↑ Thatcher, 1991 , pp. 244-245.

- ↑ Dunford, Liu, 2017 , pp. 3-4, 14.

- ↑ Glenn, 2012 , pp. 75, 79.

- ↑ Anderson, 1991 , p. 128.

- ↑ Schultz, 2014 , s. 252.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Lichtheim, 2015 , p. 333.

- ↑ Skilling, 1961 , p. eleven.

- ↑ Anweiler, 1975 , p. 279.

- ↑ Howard, King, 1989 , p. 232.

- ↑ Skilling, 1961 , p. 23.

- ↑ Saccarelli, 2008 , pp. 99-101, 247-248.

- ↑ Löwy, 2010 , pp. 51-57.

- ↑ Brossat, 1974 , pp. 16-20.

- ↑ Howard, King, 1989 , p. 223.

- ↑ Howard, King, 1989 , p. 222.

- ↑ Howard, King, 1989 , p. 224.

- ↑ Knei-Paz, 1978 , p. 82.

- ↑ Deutscher, 2006 , p. 164.

- ↑ Trotsky, 1906 , p. 286.

- ↑ Felshtinsky, Chernyavsky, 2012 , p. [88] - [89].

- ↑ Münster, 1973 , s. 12, 40.

- ↑ 1 2 Berend, 2016 , p. 131.

- ↑ 1 2 Kingston-Mann, 1979 , p. 439.

- ↑ 1 2 Howard, King, 1989 , p. 225.

- ↑ 1 2 Felshtinsky, Chernyavsky, 2012 , p. [89].

- ↑ 1 2 Deutscher, 2006 , p. 171.

- ↑ Howard, King, 1989 , pp. 237-238.

- ↑ 1 2 Felshtinsky, Chernyavsky, 2012 , p. [90].

- ↑ Berend, 1998 , pp. 203-204.

- ↑ Pantsov, 2013 , pp. 12-13.

- ↑ 1 2 Berend, 1998 , p. 204.

- ↑ Wistrich, 1982 , p. 62.

- ↑ Vasetsky, 1990 , p. 40.

- ↑ Tetsch, 1973 , s. 86-87.

- ↑ Deutscher, 2006 , p. 170.

- ↑ Galai, 2002 , pp. 73-74, 265.

- ↑ Naarden, 2002 , pp. 198-199.

- ↑ Neumann, 2016 , p. 76.

- ↑ Gaidar, 2005 , p. 286-287.

- ↑ Skilling, 1961 , p. 12.

- ↑ Trotsky, 1906 , p. 278.

- ↑ Neumann, 2016 , pp. 75-77.

- ↑ Stites, 1988 , p. 40.

- ↑ Parvus, 1906 .

- ↑ Martyshin, 2016 , p. [703].

- ↑ Milyukov, 1896-1898 .

- ↑ Berlin 1960 , pp. xv — xviii.

- ↑ Rowney, 1977 , p. thirty.

- ↑ Perrie, 1973 , pp. 411, 413.

- ↑ Billington, 2011 , p. 640.

- ↑ Thatcher, 2005 , pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Howard, King, 1989 , pp. 225, 229-230.

- ↑ Slavin, 1980 , p. 73.

- ↑ Larsson, 1970 , p. 286.

- ↑ Neumann, 2016 , p. 74.

- ↑ 1 2 Saccarelli, 2008 , p. 99.

- ↑ Anderson, 1991 , p. 22.

- ↑ Deutscher, 2006 , p. 169.

- ↑ Anderson, 1991 , p. 146, 128.

- ↑ Deutscher, 2006 , p. 173.

- ↑ Deutscher, 2006 , p. 161-162.

- ↑ Deutscher, 2006 , p. 172.

- ↑ Marx, 1955 , p. 13.

- ↑ Bagaturia, 1983 , p. 420-421.

- ↑ Howard, King, 1989 , p. 227.

- ↑ Zeman, Charlau, 2007 , p. [251].

- ↑ Anweiler, 1975 , p. 87.

- ↑ Pantsov, 2013 , p. 13.

- ↑ Kingston-Mann, 1979 , pp. 449–452.

- ↑ Billington, 2011 , pp. 468, 598.

- ↑ Deutscher, 2006 , p. 166.

- ↑ Rowney, 1977 , p. 31.

- ↑ Vasetsky, 1990 , p. 439.

- ↑ Twiss, 2015 , p. 34.

- ↑ Skilling, 1961 , pp. 12, 29-30.

- ↑ Pantsov, 2013 , pp. 12-16.

- ↑ Zarodov, 1981 , p. 233.

- ↑ Meyer, 1957 , pp. 140-144, 266-267.

- ↑ Carr, 1951 , pp. 53-63.

- ↑ Plamenatz, 1954 , pp. 283-287.

- ↑ Felshtinsky, Chernyavsky, 2012 , p. [85] - [87].

- ↑ Deutscher, 1973 , p. 18.

- ↑ Day, 2013 , p. 229-234.

- ↑ Thatcher, 2005 , pp. 38-39.

- ↑ Schurer, 1961 , pp. 466-467, 471.

- ↑ Tyutyukin, Shelokhaev, 1996 , p. 75.

- ↑ Tyutyukin, 2002 , p. 227.

- ↑ Martov, 1905 .

- ↑ Tyutyukin, 2002 , p. 228.

- ↑ Martynov, No. 90, 1905 .

- ↑ Martynov, No. 93, 1905 .

- ↑ Martynov, No. 95, 1905 .

- ↑ Tyutyukin, 2002 , p. 113.

- ↑ Tyutyukin, 2002 , p. 116.

- ↑ Tyutyukin, 2002 , p. 157-158.

- ↑ Rowney, 1977 , p. 33.

- ↑ Schurer, 1961 , pp. 470-471.

- ↑ Thatcher, 2005 , pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Thatcher, 2005 , pp. 40-42.

- ↑ Reiman, 1994 , p. 195-201.

- ↑ Stepanov, 1993 , p. 160-163.

- ↑ Orlova, 2017 .

- ↑ 1 2 Vasetskiy, 1990 , p. 414.

- ↑ Straus, 1998 , p. 295.

- ↑ 1 2 Carr, 1951 , p. 58.

- ↑ Tyutyukin, Shelokhaev, 1996 , p. 73-74.

- ↑ Trotsky, 1919 , p. 4-5.

- ↑ Trotzki, 1909 .

- ↑ Scherrer, 2005 .

- ↑ Thatcher, 2005 , pp. 36, 102.

- ↑ Tyutyukin, Shelokhaev, 1996 , p. 74.

- ↑ Howard, King, 1989 , p. 239.

- ↑ Heyman, 1976 , p. 96.

- ↑ Sinclair, 1989 , pp. 1245-1246.

- ↑ Nelson, 1988 , p. 135.

- ↑ Trotsky, 1969 , p. 25.

- ↑ Trotsky, 1922 , foreword, p. 8-9.

- ↑ Sinclair, 1989 , p. 22.

- ↑ Sinclair, 1989 , p. 23.

Literature

- Books

- Anderson P. Reflections on Western Marxism; On the paths of historical materialism . - M .: Inter-Verso, 1991 .-- 271 p. - 10,000 copies. - ISBN 5-85217-009-7 .

- Bagaturia G. A. “German ideology” // Philosophical Encyclopedic Dictionary / Ch. Edition: L. F. Ilyichev , P. N. Fedoseev , S. M. Kovalev , V. G. Panov . - M .: Soviet Encyclopedia , 1983.- 840 p. - 150,000 copies.

- Vasetsky N. A. L. D. Trotsky: Political portrait // On the history of the Russian revolution / L. D. Trotsky ; Comp., Ed. biographer. essay and note. N.A. Vasetsky. - M .: Politizdat , 1990 .-- 447 p. - 150,000 copies. - ISBN 5-250-01372-4 .

- Gaidar E.T. Marxism and the preparation of the ideological foundations of a socialist experiment // Long time. Russia in the world: essays on economic history . - M .: Case, 2005 .-- 656 p. - ISBN 5-7749-0389-3 .

- R. B. Day. Leon Trotsky and the policy of economic isolation = Leon Trotsky and the Politics of Economic Isolation / scientific. ed. A. A. Belykh; per. from English A.V. Belykh. - M .: Case, 2013. - 469, [1] p. - (Economic history in the past and present / Russian Acad. National Economy and Public Administration under the President of the Russian Federation). - 1000 copies. - ISBN 978-5-7749-0766-3 .

- Deutscher I. “Permanent revolution” // Trotsky. Armed Prophet. 1879-1921 . - M .: Tsentrpoligraf , 2006 .-- 527 p. - ISBN 5-9524-2147-4 .

- Emelyanov Yu. V. Among the waves of the revolutionary storm // Trotsky. Myths and personality. - M .: Veche, 2003 .-- 477 p. - (Dossier without retouching). — ISBN 5-94538-345-7 .

- Зародов К. И. Ленинизм и современные проблемы перехода от капитализма к социализму. - 2nd ed., Revised. and add. — М. : Мысль , 1981. — 469 с.

- Земан З. , Шарлау У. Санкт-Петербург, 1905 // Кредит на революцию. План Парвуса. — М. : Центрполиграф , 2007. — 436 с. — ISBN 978-5-9524-2941-3 .

- Маркс К. , Энгельс Ф. Немецкая идеология // Собрание сочинений. - 2nd ed. — М. : Политиздат , 1955. — Т. 3. — 689 с.

- Марксистская политическая и правовая мысль // История политических и правовых учений. Учебник / под общ. ed. О. В. Мартышина . - 3rd ed., Revised. and add. — М. : «Проспект», 2016. — 800 с. — ISBN 9785392205615 . — ISBN 978-5-392-20817-3 .

- Милюков П. Н. Очерки по истории русской культуры. 3 части = Очерки по исторіи русской культуры. - SPb. : Издание журнала «Мир Божий», 1896—1898. — 984 с.

- Милюков П. Н. Очерки по истории русской культуры. — М. : Директмедиа Паблишинг, 2007. — 4144 с. — ISBN 978-5-94865-218-4 .

- Парвус . Россия и революция. - SPb. : книгоиздательство Н. Глаголева, 1906. — 264 с.

- Тютюкин С. В. Меньшевики в начале революции // Меньшевизм: страницы истории. — М. : РОССПЭН , 2002. — 560 с. - 1,500 copies — ISBN 5-8243-0310-X .

- Тютюкин С. В. , Шелохаев В. В. Теория «перманентной» революции // Марксисты и русская революция (1905 — февраль 1917 г.). — М. : РОССПЭН , 1996. — 240 с. - 2000 copies. — ISBN 5-86004-041-5 .

- Фельштинский Ю. , Чернявский Г. Концепция перманентной революции // Лев Троцкий. Книга 1. Революционер. 1879—1917 гг. — М. : Центрполиграф , 2012. — 448 с. — ISBN 978-5-227-03783-1 .

- Anweiler O. Rätebewegung in Russland, 1905—1921. — Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group , 1975. — 337 p. — ISBN 9780394471051 . — ISBN 0394471059 .

- The centrally planned economic system // An Economic History of Twentieth-Century Europe: Economic Regimes from Laissez-Faire to Globalization. — Cambridge University Press , 2016. — 368 p. — ISBN 9781107136427 . — ISBN 1107136423 .

- Decades of Crisis: Central and Eastern Europe Before World War II. — University of California Press, 1998. — 437 p. — ISBN 9780520206175 . — ISBN 0520206177 .

- Berlin I. Introduction // Roots of revolution: a history of the populist and socialist movements in nineteenth century Russia = Il populismo Russo / Fr. Venturi . — Knopf, 1960. — 850 p. — ISBN 9781842122532 . — ISBN 1842122533 .

- Billington JH Пожар в умах человеческих: происхождение Революционной веры = Fire in the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith. — Transaction Publishers, 2011. — 677 p. — ISBN 9781412814010 . — ISBN 1412814014 . — ISBN 0-465-02405-X .

- Aux origines de la révolution permanente: la pensée politique du jeune Trotsky. — F. Maspero, 1974. — 319 p. — (Les Textes à l'appui. Histoire contemporaine).

- Carr EH The Man and the Instrument: 1905 and After // A History of Soviet Russia: The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917—1923. — Macmillan, 1951. — Т. 1. — 557 p.

- Deutscher I. Introduction // The Age of Permanent Revolution: A Trotsky Anthology. — New York: Dell Publishing, 1973. — 384 p.

- Galai S. The birth of the democratic intelligentsia // The Liberation Movement in Russia 1900—1905. — Cambridge University Press , 2002. — 336 p. — (Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies, Vol. 10). — ISBN 9780521526470 . — ISBN 0521526477 .

- Howard MC , King JE Trotsky on Uneven and Combined Development // A History of Marxian Economics. — Princeton University Press , 1989. — Т. I: 1883—1929. — 374 p. — (Princeton Legacy Library, 1). — ISBN 9781400860524 . — ISBN 1400860520 .

- Knei-Paz B. Социальная и политическая мысль Льва Троцкого = The Social and Political Thought of Leon Trotsky. — 1st. — Oxford University Press , 1978. — 652 p. — ISBN 9780198272335 . — ISBN 0198272340 .

- Larsson R. Theories of Revolution: From Marx to the First Russian Revolution. — Stockholm: Almqvist och Wiksell, 1970. — 381 p. — (Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis: Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala, Issues 51—53).

- Lichtheim G. Marxian Socialism 1871—1918 // Marxism (RLE Marxism): An Historical and Critical Study. — Routledge , 2015. — 434 p. — (Routledge Library Editions: Marxism). — ISBN 9781317497004 . — ISBN 1317497007 .

- Löwy M. Permanent revolution in Russia // The Politics of Combined and Uneven Development: The Theory of Permanent Revolution. — Haymarket Books, 2010. — 162 p. — ISBN 9781608460687 . — ISBN 1608460681 .

- Mendel AP The Birth and Triumph of Russian Marxism // Dilemmas of progress in tsarist Russia: legal Marxism and legal Populism. — Harvard University Press , 1961. — 310 p. — (Russian Research Center studies, Vol. 43). — ISBN 978-0-674-42076-2 .

- Leninism. - 3rd. — Harvard University Press , 1957. — 324 p. — (Praeger university series; Russian Research Center studies, Vol. 26).

- Trotzkis Theorie der permanenten Revolution. — Luchterhand, 1973. — 119 p. — (Luchterhand Typoskript). — ISBN 9783472770183 . — ISBN 347277018X .

- Naarden B. 1905 a failed revolution in Russia // Socialist Europe and Revolutionary Russia: Perception and Prejudice 1848—1923. — Cambridge University Press , 2002. — 604 p. — (Perception and Prejudice 1848). — ISBN 9780521892834 . — ISBN 052189283X .

- Nelson HW Leon Trotsky and the Art of Insurrection, 1905—1917. — Routledge , Psychology Press, 1988. — 158 p. — (Cass Series on Politics and Military Affairs, Book 1). — ISBN 9780714632728 . — ISBN 0714632724 .

- From the assassination of Tsar Alexander II to the First World War // Russia and the Idea of Europe: A Study in Identity and International Relations. — Taylor & Francis , 2016. — 232 p. — (New International Relations). — ISBN 9781317294702 . — ISBN 131729470X .

- Pantsov A. The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Revolution 1919—1927. — Routledge , 2013. — 352 p. — (Chinese Worlds). — ISBN 9781136828935 . — ISBN 1136828931 . — ISBN 0-7007-1187-2 .

- German Marxism and Russian Communism. — Longmans, Green & Co. , 1954. — 356 p. — (Harper torchbooks).

- Saccarelli E. Gramsci and Trotsky in the Shadow of Stalinism: The Political Theory and Practice of Opposition. — Routledge , 2008. — 320 p. — ISBN 9781135899806 . — ISBN 1135899800 .

- Schultz H. Leo Trotzki, 1879—1940. Luzifer der Revolution // Europäischer Sozialismus immer anders. — Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag (BWV), 2014. — 566 p. — ISBN 9783830533108 . — ISBN 3830533101 .

- Sinclair L. Trotsky. A Bibliography. 2 vol. — Camelot Press Ltd. — Brookfield: Gover Publishing Company, 1989. — Т. 2. — 1350 p. — ISBN 0-85967-820-2 .

- Stites RT Revolution: Utopias in the Air and on the Ground. A new World // Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution. — Oxford University Press , 1988. — 324 p. — ISBN 9780195363678 . — ISBN 0195363671 .

- Straus KM Factory and Community in Stalin's Russia: The Making of an Industrial Working Class. — University of Pittsburgh Press, 1998. — 378 p. — (Pitt Russian East European). — ISBN 9780822977254 . — ISBN 0822977257 .

- Tetsch H. Trotzki: «Ergebnisse und Perspektiven» // Die Permanente Revolution: Ein Beitrag zur Soziologie der Revolution und zur Ideologiekritik. — Westdeutscher Verlag; Springer , 1973. — 256 p. — (Beiträge zur sozialwissenschaftlichen Forschung, 11). — ISBN 9783531111933 . — ISBN 3531111930 . — ISBN 978-3-663-01710-3 .

- Thatcher ID The Young Revolutionary // Троцкий = Trotsky. — Routledge , 2005. — 264 p. — (Routledge Historical Biographies). — ISBN 9781134572144 . — ISBN 113457214X .

- Thatcher ID Leon Trotsky and 1905 // The Russian Revolution of 1905: Centenary Perspectives / ed. AJ Heywood , JD Smele . — Routledge , 2013. — 336 p. — (Routledge Studies in Modern European History, Vol. 9). — ISBN 9781134253302 . — ISBN 1134253303 .

- Treadgold DW The West in Russia and China: Religious and Secular Thought in Modern Times. — Cambridge University Press , 1973. — Т. 1. Russia, 1472—1917. — 324 p. — ISBN 9780521097253 . — ISBN 0521097258 .

- Trotsky L. The permanent revolution and Results and prospects. - 3rd. — Merit Publishers, 1969. — 281 p. — ISBN 0932323294 . — ISBN 9780932323293 .

- Twiss TM The Socialist Movement and Post-Revolutionary Bureaucracy // Trotsky and the Problem of Soviet Bureaucracy. — Haymarket Books, 2015. — 502 p. — (Historical Materialism Book Series, Vol. 67). — ISBN 9781608464784 . — ISBN 9789004269538 .

- Wistrich RS Trotsky : fate of a revolutionary. — New York: Stein and Day, 1982. — 235 p. — ISBN 9780812827743 . — ISBN 0812827740 .

- Articles

- Мартов Ю. О. На очереди. Рабочая партия и «захват власти», как наша ближайшая задача // Искра : газета. — 1905. — 17 марта ( № 93 ).

- Мартынов А. Революционные перспективы // Искра : газета. — 1905. — 3 марта ( № 90 ).

- Мартынов А. Революционные перспективы // Искра : газета. — 1905. — 17 марта ( № 93 ).

- Мартынов А. Революционные перспективы // Искра : газета. — 1905. — 31 марта ( № 95 ).

- Орлова М. Еще раз вокруг гибели поэтессы Надежды Львовой // Октябрь : журнал. — 2017. — № 4 .

- Парвус А. Итоги и перспективы // Искра : газета. — 1905. — 27 января ( № 85 ). - S. 2-4 .

- Рейман М. Заметки по интерпретации 1917 года // Отечественная история : журнал / Институт российской истории РАН . — 1994. — № 4—5 . — С. 195—204 .

- Степанов А. И. Место России в мире накануне Первой мировой войны // Вопросы истории : журнал / РАН . — 1993. — № 2 . — С. 156—163 .

- Шеррер Ю. Революция без революционеров. 1905 год в сегодняшних российских школьных учебниках // Неприкосновенный запас : журнал. — 2005. — Т. 6 , вып. 44 . — ISSN 0869-6365 .

- Brahm H. Trockijs Aufrufe gegen Hitler 1930—1933 (нем.) // Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. — 1963. — Bd. 11 , H. 4 . — S. 521—542 . — ISSN 0021-4019 .

- Leon Trotsky (англ.) // Encyclopædia Britannica . — 2016. — 30 June.

- Davies DA 1905. By Trotsky Leon . Translated by Bostock Anya . Studies in the Third World Books. New York: Random House, 1971. xxi, 488 pp. $15.00. (англ.) // Slavic Review. — 1973. — December ( vol. 32 , iss. 4 ). — P. 817—818 . — ISSN 0037-6779 . — DOI : 10.2307/2495516 .

- Dunford M. , Liu W. Uneven and combined development (англ.) // Regional Studies. — 2017. — January ( vol. 51 , iss. 1 ). — P. 69—85 . — ISSN 0034-3404 . — DOI : 10.1080/00343404.2016.1262946 .

- Glenn J. Uneven and combined development: a fusion of Marxism and structural realism (англ.) // Cambridge Review of International Affairs. — 2012. — March ( vol. 25 , iss. 1 ). — P. 75—95 . — ISSN 0955-7571 . — DOI : 10.1080/09557571.2011.649245 .

- Heyman NM Leon Trotsky's Military Education: From the Russo-Japanese War to 1917 (англ.) // The Journal of Modern History. — 1976. — June ( vol. 48 , iss. S2 ). — P. 71–98 . — ISSN 0022-2801 . — DOI : 10.1086/241524 .

- Kingston-Mann E. Lenin and the Challenge of Peasant Militance: From Bloody Sunday, 1905 to the Dissolution of the First Duma (англ.) // The Russian Review. — 1979. — Vol. 38 , iss. 4 . — P. 434—455 . — DOI : 10.2307/129123 .

- Perrie M. The Socialist Revolutionaries on «Permanent Revolution» (англ.) // Soviet Studies. — 1973. — Vol. 24 , iss. 3 . — P. 411–413 . — ISSN 0038-5859 .

- Rowney DK Development of Trotsky's theory of revolution, 1898—1907 (англ.) // Studies in Comparative Communism. — 1977. — March ( vol. 10 , iss. 1 ). — P. 18—33 . — DOI : 10.1016/S0039-3592(77)80072-0 .

- Schurer H. The Russian Revolution of 1905 and the Origins of German Communism (англ.) // The Slavonic and East European Review. — 1961. — Vol. 39 , iss. 93 . — P. 459—471 . — ISSN 0037-6795 .

- Permanent or Uninterrupted Revolution: Lenin, Trotsky, and their Successors on the Transition to Socialism (англ.) // Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne des Slavistes. — 1961. — Vol. 5 . — P. 3—30 . — ISSN 0008-5006 .

- Slavin M. Review of Leon Trotsky; The Social and Political Thought of Leon Trotsky; With Trotsky in Exile: From Prinkipo to Coyoacán (Eng.) // International Labor and Working-Class History. - 1980 .-- Spring ( iss. 17 ). - P. 71-76 . - DOI : 10.2307 / 27671315 .

- Thatcher ID Uneven and combined development (Eng.) // Revolutionary Russia. - 1991 .-- December ( vol. 4 , iss. 2 ). - P. 235—258 . - ISSN 0954-6545 . - DOI : 10.1080 / 09546549108575572 .