The Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens ( French Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne ) was written in 1791 by the French revolutionary activist, feminist and writer Olympia de Gouges in response to the Declaration of Human Rights and Citizen . By publishing this document, de Gouges hoped to draw public attention to the fact that the French Revolution , declaring equality, did not recognize the equal rights of men and women . However, the declaration did not have a real impact on the course of the revolution. As a result of the publication of his political writings, including a declaration, de Gouges was accused of treason and executed along with a number of Girondins during the era of terror . She was one of three women decapitated at that time and the only one executed for political publications.

The Declaration was not a manifesto of the organized women's movement, but formulated the idea of full women's equality, for which feminism began to fight a considerable time later.

Historical Context

The "Declaration of Human and Citizen Rights" was approved in 1789 by the Constituent Assembly during the French Revolution. The document declared "natural and inalienable" human rights in relation to the state. [1] The Declaration rejected discrimination and inequality on the basis of religious and social differences [2] , but ignored the rights of women.

In 1790, the Marquis de Condorcet tried unsuccessfully to call on the Constituent Assembly to grant women political and civil rights as well [2] . Condorcet said that "one who votes against the rights of others because of differences in religion, color or gender calls into question his own." [one]

At the initial stage, French women actively participated in the revolution. In October 1789, they were the leading force in the campaign against Versailles , which was caused by a shortage of bread in Paris. As a result of this campaign, the royal family was actually captured, and the Constituent Assembly moved to Paris and lost many royalist deputies who did not go to Paris because of fears for their own lives. This had a significant impact on the further course of the revolution. However, the leaders of the revolution "did not notice" the participation of women in this event and did not extend to them the "natural and inalienable" human rights. [3] [4]

After going to Versailles in November 1789, a group of women filed a petition at the Constituent Assembly demanding equality and recognition of the natural and political rights of women. This petition was never considered by the Constituent Assembly. .

Thus, the French revolution did not lead to the recognition of women 's rights . This forced Olympia de Gouges in early 1791 to publish the “Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens” [5] .

Declaration

The declaration was published in the brochure "Women's Rights", addressed to the Queen Error in the footnotes ? : Wrong call: wrong keys, for example, too many keys were indicated or the key was wrong and begins with a call to Marie Antoinette , the “most hated” of all women.

| This revolution will achieve its goal only when all women are fully aware of their deplorable situation and their rights, which they have been deprived of in society. |

De Gouge calls on the queen not to plot against her country, but to defend the rights of women and thus gain "support for half the kingdom." Error in the footnotes ? : Invalid call: invalid keys, for example, too many keys were specified or the key was incorrect .

After a detailed appeal to the queen, a brief appeal to men follows.

| Man, are you capable of being fair? Would you allow a woman to at least ask you this question? Who gave you the imperial right to enslave a woman? Your power Your talents ... we demand equality and nothing more [6] . |

Further, the declaration of de Gouges is built in the image of the “Declaration of Human Rights and Citizen”, consistently reproduces the preamble, 17 articles and looks “almost a parody of the original document” [5] .

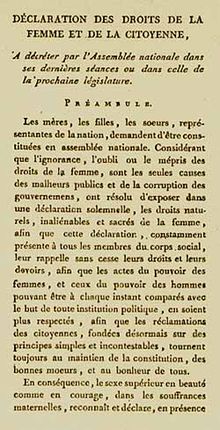

Preamble

In the preamble of de Gouges, reproducing the solemn style of the preamble of the “Declaration of Human and Citizen Rights”, it clarifies that women, like men, have “natural, inalienable and sacred rights” and that political institutions exist to protect these rights [6] .

Declaration Articles

Article I

The first article of the declaration of human and civil rights states that “People [7] are born free and equal in rights. Social differences are permissible only for the common good. ” The first article of the de Gouges declaration states: “Women are born free and equal with men in rights. Social differences are permissible only for the common good ” [6] .

Articles II and III

Articles II and III extend the articles of the original declaration to women [6] .

Article IV

In article IV, de Gouges states that “the eternal tyranny of men is the only limit to a woman’s natural rights” and requires reform to ensure that society protects the natural rights of all its members by law [6] .

Article V

Article V reproduces the article of the original declaration. [6]

Articles VI - IX

Articles VI - IX extend the effect of the articles of the original declaration to women [6] .

Article X

In article X de Gouges draws attention to the fact that, according to French laws, women are responsible for their actions on an equal footing with men, but they are denied rights and make a well-known statement that has become prophetic for herself: “A woman has the right to climb the scaffold, she has the right to ascend the rostrum. " [eight]

Article XI

In this article, de Gouges states that a woman has the right to identify the father of her child and demand material support from him. Some historians believe that this is due to the fact that de Gouges considered herself an illegitimate child [9] .

Article XII

In this article, de Gouges explains that recognizing the rights of women is a boon to society as a whole, and not just to women. [9]

Articles XIII - XVI

Articles XIII - XVI extend the effect of the articles of the original declaration to women [6] .

Article XVII

This article declares the equality of men and women in marriage in the face of the law, which primarily concerns the rights to divorce and property [6] [10] .

Postscript Declaration

The postscript of the declaration begins with a call for women to “wake up and fight for their rights” [6] . In the first paragraph, de Gouges draws the attention of women to what the revolution gave them - "even greater neglect, even greater contempt." Further, de Gouges advocates for the progress of women in society, for women's education and discusses the issue of marriage, which in her opinion remains “the grave of trust and love” [6] .

On the basis of the “Social Contract” by Jean-Jacques Rousseau de Gouges, he develops in detail the ideas of equal marriage. As in the case of the “Declaration of Human Rights and Citizen”, de Gouges summarizes the ideas of Rousseau's social contract on the basis of recognition of the full equality of man and woman [11] . Marriage must be a voluntary union of equal partners. All children born in marriage have the right to the name of the father and mother “regardless of their origin” [6] .

Declaration Response

After the publication of the “Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens”, radical revolutionaries suspected de Gouges of treason. Since the declaration was addressed to the queen, the Jacobins, led by Robespierre, considered her compiler royalist. When de Gouges tried to publish a note demanding a referendum on the future form of government, which suggested choosing from three options, including a constitutional monarchy, the Jacobins accused her of treason. She was quickly convicted and executed on the guillotine, like many other "political enemies" of the "united and indivisible" republican France of the era of terror. [five]

After the execution, the Paris press ceased to be ironic about its "harmless nonsense." Agreeing that the programs and plans of de Gouges for France were far from reality, journalists wrote that she tried to act as a “statesman”. According to the Feuille du Salut public (Herald of Public Salvation ), her crime was that she “forgot about the virtues of her gender.” The ideas of female equality were alien to Jacobin Paris, feminism and de-gugee political activism unseemly for women seemed dangerous to the revolution. [five]

De Gouges was an implacable critic of the principle of equality proclaimed by the French Revolution, as he ignored the rights of women and non-whites. Her many plays on the rights of women and people of color have drawn public attention to this topic, not only in France, but also in Europe and the newly created United States . [five]

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 Lauren, Paul Gordon. The evolution of international human rights . - University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003. - P. 18–20. - ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1 .

- ↑ 1 2 Williams, Helen Maria. Letters written in France . - Broadview Press Ltd, 2001. - P. 246. - ISBN 978-1-55111-255-8 .

- ↑ Lynn Avery Hunt, The challenge of the West: Peoples and cultures from 1560 to the global age , p. 672, DC Heath, 1995.

- ↑ The Monstrous Regiment of Women: Revolutionary Women - The Women's March on Versailles . www.monstrousregimentofwomen.com . Date of treatment December 16, 2015.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Naish, Camille. Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933 . - Routledge, 1991 .-- P. 136. - ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 LES DROITS DE LA FEMME - Olympe de Gouges . www.olympedegouges.eu . Date of treatment November 30, 2015.

- ↑ The word “l'homme” used in this declaration in French means only a man.

- ↑ Naish, Camille. Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933 . - Routledge, 1991. - P. 137. - ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7 .

- ↑ 1 2 Blanc, Olivier. Olympe de Gouges. - Syros, 1981. - ISBN 978-2901968542 .

- ↑ In France of this period, a married woman did not have the right, without the permission of her husband, to go to court and dispose of her property. Subsequently, this lack of rights of women was enshrined in the code of Napoleon .

- ↑ von Guttner, Darius (2015). The French Revolution . Nelson Cengage pp. 34–35.