Carcharhinus perezii (lat.) - a species of cartilaginous fish of the genus of gray sharks of the same family of the order Karhariniformes . The maximum recorded length is 295 centimeters. These sharks live in the Western Atlantic and the Caribbean from Florida ( USA ) to Brazil at a depth of up to 378 m.They have a streamlined body of a fusiform shape characteristic of gray sharks, so they are difficult to distinguish, for example, from dark and silk sharks .

| Carcharhinus perezii |

|

| Scientific classification |

|---|

| No rank : | Bilateral symmetrical |

| Subfamily : | Gray or Sawtooth Sharks |

| View: | Carcharhinus perezii |

|

| International scientific name |

|---|

Carcharhinus perezii ( Poey , 1876) |

| Synonyms |

|---|

- Platypodon perezii Poey, 1876

- Carcharhinus perezi (Poey, 1876)

- Eulamia springeri Bigelow et Schroeder , 1944

- Carcharhinus springeri (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1944) [1]

|

| Area |

|---|

|

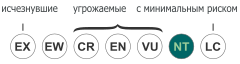

| Security status |

|---|

Close to vulnerableIUCN 3.1 Near Threatened : 60217 |

|

Carcharhinus perezii is a viviparous species. There are up to 6 newborns in the litter. Pregnancy lasts about a year. These sharks are nocturnal and do not migrate. The basis of the diet are various bony and cartilaginous fish . They are potentially dangerous to humans, but generally not aggressive. Of interest to ecotourism. These sharks are obtained in a commercial and artisanal way, meat is eaten [2] [3] .

Content

For the first time, the species was scientifically described by Cuban zoologist Felipe Poei as Platypodon perezi [4] based on the study of 6 individuals caught off the coast of Cuba . Later authors recognized the genus Platypodon as a synonym for the genus of gray sharks [5] . The species is named after the friend and companion Felipe Poey Laureano Pérez Arcas ( Spanish: Laureano Pérez Arcas ), an employee of the University of Madrid, the author of the textbook “Elementos de Zoología”, which the researcher used during his work at the University of Havana [6] .

Original image of teeth of the species

Carcharhinus perezii Based on morphological similarities, the New Zealand ichthyologist Jack Garrick in 1982 combined Carcharhinus perezii , Carcharhinus altimus and the blue-gray shark into one group, while Leonard Compagno recognized Carcharhinus perezii and Carcharhinus amblyrhynchoides as closely related species in 1988. A phylogenetic analysis conducted in 1992 showed that Carcharhinus perezii is a closely related taxon of the clade formed by the Galapagos , dark , long-winged and blue shark. However, additional studies are needed to accurately determine the taxonomic relationships of gray sharks [7] .

This species does not yet have a Russian-speaking officially accepted scientific name, but colloquially they are sometimes called Caribbean reef sharks [8] .

These sharks live in the tropical waters of North, Central and South America, having the greatest distribution in the waters of the Caribbean in the waters of Florida , Bermuda , Yucatan , Cuba , Jamaica , Bahamas , Mexico , Puerto Rico , Colombia , Venezuela and Brazil . They are found in shallow water, around coral reefs and near the edge of underwater cliffs at a depth of up to 378 meters, however, they rarely go deeper than 30 m. Sometimes Carcharhinus perezii are found in muddy areas in deltas of Brazilian rivers [9] .

The upper lobe of the caudal fin is very elongated in these sharks.

Carcharhinus perezii has a strong spindle-shaped body and a wide, rounded, short snout. The large mouth has an arc shape with triangular serrated teeth. Each jaw has 22-26 dentitions. Teeth with a wide base end with a point narrower on the lower jaw. The edges of the teeth are jagged. The eyes are large and round, equipped with a blinking membrane . Five pairs of gill slits are quite long, the third pair is located at the level of the beginning of the base of the pectoral fins [10] . The first dorsal fin is slightly sickle-shaped with a large curved posterior margin. The second dorsal fin is much smaller than the first. Between the dorsal fins there is a low crest. The base of the first dorsal fin is located at the end of the free posterior ends of the pectoral fins, and the base of the second lies in front of the base of the anal fin. Crescent-shaped pectoral fins are well developed and taper to the ends [5] . The caudal fin is asymmetrical. The back is gray or taupe. The belly is white. The average adult size is 152-168 centimeters. The maximum recorded length is 295 centimeters, and weight - 70 kg [11] [12] . Skin folds in the nostrils are absent.

The dorsal surface of the body is gray-brown, and the ventral surface is white or yellowish-white. On the sides lie slightly noticeable stripes. There are no clear marks on the fins, however, the lower surface of the paired fins, the anal fin and the lower lobe of the caudal fin are darker than the main background [5] [10] . The skin is densely covered with overlapping placoid flakes [10] .

Carcharhinus_perezii often rise to the very surface of the water

Despite the fact that these sharks are widespread in the Caribbean, they have not been studied much in comparison with other large species of gray sharks. Lead a nocturnal lifestyle. No seasonal changes in activity and migrations are observed. Young sharks of this species often have a limited individual habitat , while adults patrol vast territories [13] .

Unlike most species of sharks, which are forced to move so that water, passing through the gill slits, supplies the body with oxygen , Carcharhinus perezii are able to lie still at the bottom, filtering water through the gill slots. In 1975, Eugenie Clark investigated this famous phenomenon in the caves of Isla Mujeres and off the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula and found that in fact the sharks are not sleeping and, judging by the movement of their eyes, are watching the divers. Clark suggested that the freshwater upward flow of water inside the caves helps sharks get rid of parasites and has a peculiar “narcotic” effect on them [14] . Being disturbed, Carcharhinus perezii begins to behave aggressively: movements become sharp, sharks rapidly change direction and lower their pectoral fins for several seconds. However, such aggressive behavior in this species is less pronounced compared to dark-gray sharks [14] [15] .

Young Carcharhinus perezii can become prey for large sharks, such as tiger or blunt sharks . The species is practically not affected by parasites. An exception is leeches that attach to the dorsal fin of this shark [10] . Along the northern coast of Brazil, young sharks of this species get rid of parasites with the help of Elacatinus randalli fish [16] . Around Carcharhinus perezii , flocks of large-eyed and red caranxes can often be observed [17] .

Nutrition

Tuna fish (in this case,

Caranx hippos ) are included in the diet of

Carcharhinus perezii , but sometimes they themselves attack the predator

The diet of Carcharhinus perezii consists mainly of a variety of bony fish that live on reefs, as well as cartilaginous fish, such as spotted bracken and stingrays Urobatis jamaicensis [3] . It is believed that this species of sharks prefers sick and wounded fish, which moves abruptly and intermittently (they say that the wounded fish "fights"). Using the sideline, the shark detects low-frequency sound vibrations, which indicates the presence of a suitable victim nearby [10] . We observed how, during the hunt for rabirubia two-meter-long male Carcharhinus perezii circled limply and made indecisive turns in its direction, and then suddenly accelerated, moved its head from side to side and grabbed the fish by the edge of the jaw [14] . Young sharks feed on small fish, shrimp and crabs [14] . Carcharhinus perezii can eject swallowed from the stomach, probably to get rid of inedible particles, parasites and mucus that strengthens the stomach [17] .

Reproduction

Carcharhinus perezii is a viviparous species, embryos develop in utero, feeding on the yolk, then the empty yolk sac is transformed into the placental connection, through which they continue to receive nutrition. In the litter from 4 to 6 newborns up to 74 cm long. In the process of mating, males often bite females, leaving numerous clearly visible scars on their skin [10] . In the Fernando di Noronha archipelago and on the Rocas Atoll in the waters of Brazil, childbirth occurs at the end of the dry season from February to April, while in other places in the Southern Hemisphere, females give birth during the rainy season in November and December [10] [18] . Pregnancy lasts for 1 year [14] . Males and females reach puberty with a length of 1.5-1.7 and 2-3 meters, respectively [10] .

These sharks are hunted commercially and artificially using longlines and gillnets. Valued meat, skin, liver fat, from the skeletons produce fishmeal . In Colombia, Carcharhinus perezii accounts for up to 39% of the total haul using longlines, where these sharks are fished for fins, fat and jaws. In Belize, they are caught by- catch when catching groupers and snappers , fins are exported to Asian markets, and meat is sold domestically. Judging by the catches, in Belize, the population size from the middle of the last century to the 90s significantly decreased [3] . Carcharhinus perezii meat may contain large amounts of methylmercury and heavy metals [10] . The International Union for Conservation of Nature has assigned this species a conservation status of “Close to Vulnerability”. Sharks of this species suffer from deterioration of living conditions due to the destruction of reefs. Their commercial fishing is prohibited in US waters [10] . In the Bahamas, they are protected as a valuable site for ecotourism.

Shark diving and hiking

Feeding Sharks from a Ship,

Queen's Gardens ,

Cuba Sharks of this species are curious and not shy. Usually in the presence of people they behave indifferently, however, when food appears, they become aggressive, large individuals can be dangerous [12] .

Ecotourism makes a good profit, in the Bahamas every year divers spend up to $ 6 million on an attraction such as watching sharks feed under water. In these places, the profit from live sharks is estimated from 13,000 to 40,000 dollars per individual, while the price for a dead shark does not exceed 50-60 dollars [19] . Sometimes, as an additional entertainment, tourists are invited to feed sharks , both underwater and on the surface. Proponents and opponents of this kind of show strongly disagree on whether shark feeding is acceptable near areas where people are densely populated and whether this kind of business affects the statistics of shark attacks on humans [14] .

Shark Feeding in the Bahamas

These sharks, although included in the list of potentially dangerous for humans, do not pose a serious threat, with the exception of situations when they are provoked to attack, for example, if a person has an open wound or during spearfishing . The Global Shark Attack File lists a number of accidents in the Bahamas related to this species of shark. Most occurred during spearfishing. And such an authoritative source as fishbase.org defines Carcharhinus perezii as “an aggressive species seen in attempts to attack divers in the Caribbean” [2] .

- ↑ FishBase: Synonyms of Carcharhinus perezii (Poey, 1876)

- ↑ 1 2 Carcharhinus perezii (Eng.) In the FishBase database.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Carcharhinus perezii (English) . The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species . Date of appeal April 16, 2014.

- ↑ Poey, F. (1876) Enumeratio piscium cubensium (Parte III). Anales de la Sociedad Española de Historia Natural, 5: P. 373-404, pl. 7-10

- ↑ 1 2 3 Compagno, Leonard JV 1. Hexanchiformes to Lamniformes // FAO species catalog. - Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 1984. - Vol. 4. Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalog of Shark Species Known to Date. - P. 492–493. - ISBN 92-5-101384-5 .

- ↑ Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara. Fish Name Etymology Database (Neopr.) . The ETYFish Project . Date of treatment April 29, 2014.

- ↑ NaylorFowler, GJP The phylogenetic relationships among requiem and hammerhead sharks: inferring phylogeny when thousands of equally most parsimonious trees result // Cladistics. - 1999. - Vol. 8, No. (4) . - P. 295-318. - DOI : 10.1111 / j.1096-0031.1992.tb00073.x .

- ↑ Mistress of the Caribbean (Neopr.) . Sharks .

- ↑ Angelo Moyeta. Sharks. History and biology of the lords of the sea. - White Star Publishers. - ISBN 88-8095-731-7 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Scharfer, A. Biological Profiles: Caribbean Reef Shark (neopr.) . Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Date of treatment April 29, 2014.

- ↑ Compagno, L., Dando, M. and Fowler, S. Sharks of the World. - Princeton University Press, 2005 .-- P. 253. - ISBN 978-0-691-120720 .

- ↑ 1 2 Ferrari, A. & Ferrari, A. Sharks. - Firefly Books, 2002. - P. 176-177. - ISBN 1-555209-629-7.

- ↑ Garla, RC, Chapman, DD, Wetherbee, BM and Shivji, M. Movement patterns of young Caribbean reef sharks, Carcharhinus perezi, at Fernando de Noronha Archipelago, Brazil: the potential of marine protected areas for conservation of a nursery ground // Marine Biology. - Vol. 149 . - P. 189-199.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Martin, RA Caribbean Reef Shark (neopr.) . ReefQuest Center for Shark Research. Date of appeal April 30, 2014.

- ↑ Martin, RA A review of shark agonistic displays: comparison of display features and implications for shark-human interactions // Marine and Freshwater Behavior and Physiology. - 2007. - Vol. 40, No. (1) . - P. 3—34.

- ↑ Sazima, I. and Moura, RL Shark ( Carcharhinus perezi ), Cleaned by the Goby ( Elacatinus randalli ), at Fernando de Noronha Archipelago, Western South Atlantic // Copeia. - 2000. - Vol. 2000, No. (1) . - P. 297-299. - DOI : 10.1643 / 0045-8511 (2000) 2000 [0297: SCPCBT] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ↑ 1 2 Brunnschweiler, JM, Andrews, PLR, Southall, EJ, Pickering, M., and Sims, DW Rapid voluntary stomach eversion in a free-living shark // Journal of Marine Biology, Ass. UK - 2005. - Vol. 85. - P. 1141-1144.

- ↑ Garla, RC, Chapman, DD, Shivji, MS, Wetherbee, BM, and Amorim, AF Habitat of juvenile Caribbean reef sharks, Carcharhinus perezi , at two oceanic insular marine protected areas in the southwestern Atlantic Ocean: Fernando de Noronha Archipelago and Atol das Rocas, Brazil // Fisheries Research. - 2006. - Vol. 81, No. 2-3 . - P. 236-241. - DOI : 10.1016 / j.fishres.2006.07.003 .

- ↑ Fowler, SL, Reed, TM and Dipper, F. Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management. - Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop. - Sabah, Malaysia .: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Species Survival Commission, 2002. - P. 47-48. - ISBN 2—8317—0650—5.

- Compagno, L., Dando, M. and Fowler, S. Sharks of the World. - Princeton University Press, 2005 .-- P. 253. - ISBN 978-0-691-120720 .

- Ferrari, A. & Ferrari, A. Sharks. - Firefly Books, 2002. - P. 176-177. - ISBN 1-555209-629-7.