In graph theory, the number of intersections cr ( G ) of a graph G is the smallest number of intersections of the edges of a flat drawing of a graph G. For example, a graph is planar if and only if its number of intersections is zero.

The mathematical starting point for studying the number of intersections was Turan's brick factory problem posed by Pal Turan , in which it was necessary to find the number of intersections of the complete bipartite graph K m, n [1] . However, the same task was posed in sociology at about the same time in connection with the construction of sociograms [2] . The task continues to play a large role in graph visualization .

Unless otherwise indicated, the number of intersections refers to graph representations using any curves. The condition of rectilinear intersections requires that all edges be line segments, which can change the answer. In particular, the number of rectilinear intersections of a complete graph is equal to the minimum number of convex quadrangles defined by the set of n points in general position, which is closely related to the happy ending problem [3] .

History

During World War II, the Hungarian mathematician Pal Turan was forced to work in a brick factory, pushing a cart loaded with bricks from kilns to warehouses. The factory had ruts from each furnace to each warehouse, and it was harder to push the cart at the intersections of the ruts, which led Turan to the task of the brick factory: what is the minimum number of intersections of the figure of a complete graph ? [4] .

Zarankiewicz tried to solve the Turan problem [5] . His proof contained a mistake, but he set the correct upper bound

for the number of intersections of the complete bipartite graph K m, n . The hypothesis that this inequality is actually equality is known as the Zarankievich hypothesis. The lower boundary is only open eleven years after publication almost simultaneously by Gerhard Ringel and Paul Kainen (Paul Chester Kainen) [6] .

The problem of determining the number of intersections of a complete graph was first posed by Anthony Hill and appeared in print in 1960 [7] . Hill and his co-author John Ernest were two constructivist artists fascinated by mathematics, and they not only formulated the problem, but also expressed for such graphs the hypothesis of the upper boundary of the number of intersections, which Richard K. Guy published in 1960 [7] . Namely, that this boundary is equal to

which gives values 1, 3, 9, 18, 36, 60, 100, 150 for p = 5, ..., 12 (sequence A000241 in OEIS ). An independent formulation of the hypothesis was given by in 1964 [8] . Saati later found out that the upper bound is reached for p ≤ 10 , and Pan and Richter (Pan, Richter) showed that it is reached for p = 11, 12

If only rectilinear arcs are allowed, more intersections are required. The number of rectilinear intersections for graphs K 5 - K 12 is 1, 3, 9, 19, 36, 62, 102, 153 (sequence A014540 in OEIS ). Values for graphs up to K 27 are known. For K 28, you need either 7233 or 7234 intersections. Further values are collected in the project “The number of rectilinear intersections” [9] . Interestingly, it is not known whether the ordinary and rectilinear number of intersections is the same for complete bipartite graphs. If Zarankievich’s conjecture is true, then the formula for the number of intersections of the complete graph is asymptotically true [10] , that is,

By April 2015, the number of intersections is known for a very small number of graph families. In particular, with the exception of a few initial cases, the number of intersections of complete graphs, complete bipartite graphs, and product cycles remains unknown. There was some success for the lower border, according to a report by de Klerk, Maharry, Pasechnik and Richter (de Klerk, Maharry, Pasechnik, Richter) [11] . A large overview of the various options is given by Schaefer [12] .

Albertson's hypothesis , formulated by Michael O. Albertson in 2007, states that among all graphs with chromatic number n, the complete graph K n has a minimal number of intersections. That is, if the Guy – Saati conjecture about the intersection number of the complete graph is true, any n -chromatic graph has the intersection number at least equal to the formula in the hypothesis. It is known that this holds for n ≤ 16 [13] .

Difficulty

In the general case, determining the number of intersections of a graph is a difficult task. Garey and Johnson (Michael Garey, David S. Johnson) in 1983 showed that this task is NP-difficult [14] . In fact, the task remains NP-hard even when it is narrowed to cubic graphs [15] and almost planar graphs [16] (graphs that become planar after removing one edge). In particular, the determination of the number of rectilinear intersections is for the existential theory of real numbers [17] .

However, there are effective algorithms for determining that the number of intersections does not exceed a fixed constant k . In other words, the problem is [18] [19] . It remains complicated for large k , such as | V | / 2. There are also effective approximation algorithms for estimating cr ( G ) on graphs with a limited degree [20] . In practice, heuristic algorithms are used, such as a simple algorithm starting with a graph without edges and gradually adding edges so as to obtain the minimum possible additional number of intersections. This algorithm is used in the distributed computing project program “The number of rectilinear intersections” [21] .

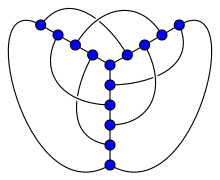

The number of intersections of cubic graphs

The smallest cubic graphs with 1-8 intersections are known (sequence A110507 in OEIS ).

The smallest cubic graphs with the number of intersections

- 1 - complete bipartite graph K 3.3 with 6 vertices.

- 2 - Petersen graph with 10 vertices.

- 3 - Earl of Howwood with 14 vertices.

- 4 - Count Mobius - Cantor with 16 vertices.

- 5 - Papp's graph with 18 vertices.

- 6 - Count of Desargues with 20 vertices.

- 7 - No (22 peaks). [22]

- 8 - graph of Nauru and graph McGee (or (3,7) - cell ) with 24 vertices.

- 2 - Petersen graph with 10 vertices.

In 2009, Ikzu (Exoo) suggested that the smallest cubic graph with 11 intersections is the Coxeter graph , with 13 intersections the Tatt – Coxeter graph , and 170 –12 Tatt cells [23] [24] .

Inequality in the number of intersections

A very useful inequality for the number of intersections was found independently by , , Newborn and Newborn and Semeredi [25] and Leighton [26] :

- For undirected simple graphs G with n vertices and e edges such that e > 7 n we have:

Constant 29 is the best known. According to Ackerman [27], constant 7 can be reduced to 4 , but this will cost the replacement of constant 29 by 64 .

The reason Leighton was interested in studying the number of intersections was an application to the development of VLSI circuits in theoretical computer science. Later, Sekay [28] also realized that this inequality provides very simple proofs of some important incidence geometry theorems, such as the Beck theorem and the Cemeredi – Trotter theorem , and Tamal Dey used the inequality to prove the upper bound of [29] .

For graphs with girths greater than 2 r and e ≥ 4 n , Pach, Spencer, and Thoth [30] showed an improvement in this inequality

Proof of inequality for the number of intersections

First, we give a preliminary estimate: for any graph G with n vertices and e edges, we have

To prove this, we represent a graph of G with exactly cr ( G ) intersections. Each such intersection can be removed along with the removal of the edge from G. Thus, we can find a graph with at least e - cr ( G ) edges and n vertices with zero number of intersections, and therefore it will be a planar graph . But from the Euler formula we must have e - cr ( G ) ≤ 3 n , whence we obtain the required inequality. (In fact, we have e - cr ( G ) ≤ 3 n - 6 for n ≥ 3 ).

To obtain the inequality of the number of intersections, we use probabilistic argumentation . Let 0 < p <1 be the probabilistic parameter that will be chosen later. We construct a random subgraph H of G by locating each vertex G in H independently with probability p and each edge G will be in H if and only if both vertices of the edge lie in H. Let e H , n H, and cr H denote the number of edges, vertices, and intersections of H, respectively. Since H is a subgraph of G , its diagram is contained in G. By the preliminary inequality of the number of intersections, we have

Calculating the mathematical expectations , we obtain

Since each of the n vertices in G has the probability p to fall into H , we obtain E [ n H ] = pn . In the same way, each edge in G has the probability p 2 to remain in H , since both ends must be in H. Thus, E [ e H ] = p 2 e . Finally, each intersection on the diagram G has a probability p 4 to remain in H , since each intersection involves four vertices. To understand this, imagine a diagram G with cr ( G ) intersections. We can assume that any two edges in this diagram do not intersect with a common vertex, otherwise we exchange parts of the edges before the intersection and the number of intersections decreases by one. Thus, we can assume that the intersection involves four different vertices of the graph G. As a result, E [cr H ] = p 4 cr ( G ) and we get

Now, if we put p = 4 n / e <1 (since we assumed that e > 4 n ), after some algebraic calculations, we get

A small change in the given argument allows replacing 64 by 33.75 for e > 7.5 n [31] .

See also

- 1-planar graph

Notes

- ↑ Turán, 1977 , p. 7-9.

- ↑ Bronfenbrenner, 1944 , p. 283-289.

- ↑ Scheinerman, Wilf, 1994 , p. 939-943.

- ↑ Pach, Sharir, 2009 , p. 126-127.

- ↑ Zarankiewicz, 1954 , p. 137-145.

- ↑ Guy, 1969 , p. 63-69.

- ↑ 1 2 Guy, 1960 , p. 68-72.

- ↑ Saaty, 1964 , p. 688-690.

- ↑ Aichholzer .

- ↑ Kainen, 1968 , p. 374-377.

- ↑ Klerk, Maharry, Pasechnik, Richter, Salazar, 2006 , p. 189-202.

- ↑ Schaefer, 2014 , p. # DS21.

- ↑ Barát, Tóth, 2009 .

- ↑ Garey, Johnson, 1983 , p. 312-316.

- ↑ Hliněný, 2006 , p. 455-471.

- ↑ Cabello, Mohar, 2013 , p. 1803-1829.

- ↑ Schaefer, 2010 , p. 334-344.

- ↑ Grohe, 2005 , p. 285-302.

- ↑ Kawarabayashi, Reed, 2007 , p. 382-390.

- ↑ Even, Guha, Schieber, 2003 , p. 231-252.

- ↑ Rectilinear Crossing Number , Graz Institute of Software Technology, University of Technology (2009).

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. Graph Crossing Number on the Wolfram MathWorld website.

- ↑ Exoo .

- ↑ Pegg, Exoo, 2009 .

- ↑ Ajtai, Chvátal, Newborn, Szemerédi, 1982 , p. 9-12.

- ↑ Leighton, 1983 .

- ↑ Ackerman, 2013 . For earlier results with other constants, see Pach and Tof Pach, Tóth, 1997 , p. 427-439, Groin, Radchik, Tardos and Toph Pach, Radoičić, Tardos, Tóth, 2006 , p. 527–552

- ↑ Székely, 1997 , p. 353–358.

- ↑ Dey, 1998 , p. 373-382.

- ↑ Pach, Spencer, Tóth, 2000 , p. 623-644.

- ↑ Ackerman, 2013 .

Literature

- P. Turán. A Note of Welcome // J. Graph Theory. - 1977.- T. 1 . - DOI : 10.1002 / jgt.3190010105 .

- Urie Bronfenbrenner. The graphic presentation of sociometric data // Sociometry. - 1944. - T. 7 , no. 3 .

- Edward R. Scheinerman, Herbert S. Wilf. The rectilinear crossing number of a complete graph and Sylvester's "four point problem" of geometric probability // American Mathematical Monthly . - 1994 .-- T. 101 , no. 10 . - DOI : 10.2307 / 2975158 .

- János Pach, Micha Sharir. 5.1 Crossings — the Brick Factory Problem // Combinatorial Geometry and Its Algorithmic Applications: The Alcalá Lectures. - American Mathematical Society , 2009. - T. 152. - (Mathematical Surveys and Monographs).

- K. Zarankiewicz. On a Problem of P. Turán Concerning Graphs // Fund. Math. - 1954.- T. 41 .

- RK Guy. Decline and fall of Zarankiewicz's Theorem // Proof Techniques in Graph Theory / ed. by F. Harary. - Academic Press, 1969.

- RK Guy. A combinatorial problem // Nabla (Bulletin of the Malayan Mathematical Society). - 1960.- T. 7 .

- TL Saaty. The minimum number of intersections in complete graphs // Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. - 1964 .-- T. 52 . - DOI : 10.1073 / pnas . 52.3.688 .

- PC Kainen. On a problem of P. Erdos // Journal of Combinatorial Theory. - 1968 .-- T. 5 . - DOI : 10.1016 / s0021-9800 (68) 80013-4 .

- E. de Klerk, J. Maharry, DV Pasechnik, B. Richter, G. Salazar. Improved bounds for the crossing numbers of K m, n and K n // SIAM Journal on Discrete Mathematics . - 2006. - T. 20 , no. 1 . - DOI : 10.1137 / S0895480104442741 . Archived July 18, 2011.

- Marcus Schaefer. The graph crossing number and its variants: a survey // The Electronic Journal of Combinatorics . - 2014.

- MR Garey , DS Johnson . Crossing number is NP-complete // SIAM J. Alg. Discr. Meth .. - 1983. - T. 4 , no. 3 . - DOI : 10.1137 / 0604033 .

- LA Székely. Crossing numbers and hard Erdős problems in discrete geometry // Combinatorics, Probability and Computing. - 1997. - T. 6 , no. 3 . - DOI : 10.1017 / S0963548397002976 .

- TL Dey. Improved bounds for planar k -sets and related problems // Discrete and Computational Geometry . - 1998. - T. 19 , no. 3 . - DOI : 10.1007 / PL00009354 .

- P. Hliněný. Crossing number is hard for cubic graphs // Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B. - 2006. - T. 96 , no. 4 . - DOI : 10.1016 / j.jctb.2005.09.09.009 .

- Cabello S., Mohar B. Adding One Edge to Planar Graphs Makes Crossing Number and 1-Planarity Hard // SIAM Journal on Computing. - 2013.- T. 42 , no. 5 . - DOI : 10.1137 / 120872310 .

- Marcus Schaefer. Complexity of some geometric and topological problems // International Symposium on Graph Drawing . - Springer-Verlag, 2010. - T. 5849. - (Lecture Notes in Computer Science). - ISBN 978-3-642-11804-3 . - DOI : 10.1007 / 978-3-642-11805-0_32 .

- M. Grohe. Computing crossing numbers in quadratic time // J. Comput. System sci. - 2005. - T. 68 , no. 2 . - DOI : 10.1016 / j.jcss.2003.07.008 .

- Ken-ichi Kawarabayashi, Bruce Reed. Computing crossing number in linear time // Proceedings of the 29th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. - 2007. - ISBN 978-1-59593-631-8 . - DOI : 10.1145 / 1250790.1250848 .

- Guy Even, Sudipto Guha, Baruch Schieber. Improved Approximations of Crossings in Graph Drawings and VLSI Layout Areas // SIAM Journal on Computing . - 2003. - T. 32 , no. 1 . - DOI : 10.1137 / S0097539700373520 .

- ET Pegg, G. Exoo. Crossing Number Graphs // Mathematica Journal. - 2009 .-- T. 11 .

- M. Ajtai, V. Chvátal, M. Newborn, E. Szemerédi. Crossing-free subgraphs // Theory and Practice of Combinatorics. - 1982. - T. 60. - (North-Holland Mathematics Studies).

- T. Leighton. Complexity Issues in VLSI. - Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1983. - (Foundations of Computing Series).

- János Pach, Joel Spencer, Géza Tóth. New bounds on crossing numbers // Discrete and Computational Geometry . - 2000. - T. 24 , no. 4 . - DOI : 10.1007 / s004540010011 .

- Eyal Ackerman. On topological graphs with at most four crossings per edge . - 2013. Archived on July 14, 2014.

- János Pach, Géza Tóth. Graphs drawn with few crossings per edge // Combinatorica . - 1997. - T. 17 , no. 3 . - DOI : 10.1007 / BF01215922 .

- János Pach, Radoš Radoičić, Gábor Tardos, Géza Tóth. Improving the crossing lemma by finding more crossings in sparse graphs // Discrete and Computational Geometry . - 2006. - T. 36 , no. 4 . - DOI : 10.1007 / s00454-006-1264-9 .

- Oswin Aichholzer. Rectilinear Crossing Number project .

- G. Exoo. Rectilinear Drawings of Famous Graphs .

- János Barát, Géza Tóth. Towards the Albertson Conjecture. - 2009.