Himantura polylepis (lat.) Is a species of the genus of stingrays -hemanturs from the family of the caudate - tailed squad of the caudate - shaped superorder of rays . They live in the tropical waters of the large rivers Indochina and Borneo , although historically they were widespread throughout South and Southeast Asia . It is one of the largest freshwater fish in the world. The maximum recorded disc width is 1.9 m. Weight can reach 600 kg. The pectoral fins of these slopes fuse with the head, forming an oval, relatively thin disk, the width of which exceeds the length. The triangular elongated snout is pointed. Thin whip-shaped tail is longer than the disc. Dermal carinae absent. Coloring of the dorsal surface of the disc of an even gray-brown color. The posterior edge of the ventral surface of the disc has a wide dark border.

| Himantura polylepis |

|---|

|

|

| No rank : | Bilateral symmetrical |

|

|

Himantura polylepis ( Bleeker , 1852) |

|

- Trygon polylepis Bleeker, 1852

- Himantura chaophraya Monkolprasit & Roberts, 1990

|

|

|

|

Endangered speciesIUCN 3.1 Endangered : 195320 |

|

Like other caudate-tailed Himantura polylepis, they reproduce by egg-production . Embryos develop in the womb, feeding on the yolk and histotroph . In the litter up to 4 newborns. The diet of these bottom fish consists mainly of small bony fish and invertebrates . They are the object of targeted fishing, are appreciated among amateur fishers and aquarists. The species suffers from environmental degradation caused by anthropogenic factors [1] [2] .

Original Image of

Trygon fluviatilisThe new species was first described in 1852 by the Danish ichthyologist Peter Blecker as Trygon polylepis [3] . The description was made on the basis of an immature specimen with a 30 cm wide disc, caught near Jakarta , Indonesia . Species epithet comes from the words of the other Greek. πολύ - “many” and others. Greek. λεπίς is the “flake” [4] . In subsequent years, the original description was revised, and in 1990 the species was re-described under the name Himantura chaophraya , which became widespread [5] . A female 78 cm long, caught in the Chauphraya river, was designated the holotype . Paratypes : a male 107 cm long and a female 192 cm long, caught in the Nan River, 360-460 km upstream of the Gulf of Thailand [6] .

In 2008, researchers concluded that Trygon polylepis and Himantura chaophraya are one and the same species, whose real name was recognized by Himantura polylepis [2] [7] .

In the waters of South, Southeast Asia and Australia, there is a complex of similar species stingrays-hematures, which were previously identified as Himantura polylepis . The Australian stingray was described as an independent species in 2008 as Himantura dalyensis . Stingrays from New Guinea probably belong to this species, and not to the species Himantura polylepis , although additional studies are needed for final confirmation [7] . Trygon fluviatilis from India, described in 1909, is very similar and may be conspecific to Himantura polylepis [5] . On the other hand, a comparison of DNA and the amino acid sequence of the stingrays of India and Thailand revealed significant differences [8] . Finally, in order to assess the degree of divergence among the Himantura polylepis populations inhabiting various reservoir basins within the range, and to determine taxonomic differentiation, further studies are needed [2] .

Given the broader evolutionary relationships of Himantura polylepis and other representatives of the stingray family, a phylogenetic analysis based on mitochondrial DNA was carried out in 2012, which showed that the most closely related species is the Urogymnus asperrimus stingrays, with which they, in turn, form a treasure with Himantura granulata and Himantura lobistoma . These data confirmed the assumption that the genus of stingrays-hematures is polyphyletic [9] .

Himantura polylepis inhabit the basins of several large rivers Indochina and Borneo. They are found in the Mekong River up to the Chan Hong district of Thailand , as well as in the Chauphray, Nan, Mekhlong , Ben Pekon , Prachin Buri and Tapi in Borneo rivers. This species of stingrays lives in the Mahakam River on Kalimantan and Kinabatangan , Sabah . Previously, they came across in the state of Sarawak , but over the past 25 years there have been no cases of capture. Historical data on the presence of this species in Myanmar , the Ganges River and the Gulf of Thailand have not yet been confirmed [2] .

Separate populations of Himantura polylepis living in different rivers are probably isolated from each other; although stingrays of this species are found in brackish waters, most likely they do not cross the sea. These bottom fish prefer a sandy and silty bottom. Sometimes, contrary to expectations, they come across densely populated urban areas [10] .

The pectoral fins of these slopes fuse with the head, forming an oval thin disc, the width of which in the front part slightly exceeds the length. The front edge forms an obtuse angle, the pointed tip of the short snout protrudes beyond the edges of the disk. Behind small eyes are sprays that exceed their size. On the ventral surface of the disk there are 5 pairs of gill slits, mouth and nostrils. Between the nostrils lies a flap of skin with a fringed lower edge. The small mouth is curved in the form of an arc; up to 7 processes are present at the bottom of the oral cavity (2–4 large processes in the center and 1–4 on the sides). Small blunted teeth are staggered and form a flat surface. The ventral fins are small and thin. The males have rather large pterygopodia [11] [5] .

Characteristic disc shape of the stingray

Himantura polylepis The whip-like, strongly thinning toward the conic and having a cylindrical section tail 1.8-2.5 times the length of the disk. There are no skin folds on the caudal peduncle. On the dorsal surface at the base of the caudal peduncle there is a single serrated spike [11] connected by ducts to the poisonous gland. At Himantura polylepis, the thorn is the longest among all stingrays and reaches a length of 38 cm [10] . The dorsal surface of the disc is densely covered with tiny heart-shaped scales, which are located in a wide strip from the area between the eyes to the base of the tail. In the central part of the disk along the spine is a row of 4-6 large plaques. The rest of the skin is dotted with small granular scales, the tail behind the spike is covered with sharp spines. Coloring of the dorsal surface of the disc of an even gray-brown color. On the edges, sometimes the disk becomes pinkish or yellowish. In living individuals, the skin is covered with a layer of dark brown mucus . The ventral surface of the disk is white and has a wide dark stripe, surrounded by numerous spots, lying along the posterior edges of the pectoral and ventral fins. The tail is black behind the spike [11] [5] [12] . The maximum recorded disk width is 1.9 m, and the total length is 5 m [12] . In the Mekong and Chaukhpray, individuals weighing 500-600 kg were found [5] [10] .

The diet of these stingrays is made up of small invertebrates, such as crustaceans and mollusks , which they detect by electroreception [10] [12] . They can often be seen at the edge of the coast, where they are likely to feed on earthworms [2] . Tapeworms Acanthobothrium asnihae , A. etini , A. masnihae , A. saliki , A. zainali [13] , Rhinebothrium abaiensis , R. kinabatanganensis and R. megacanthophallus [14] parasitize Himantura polylepis .

Like other caudate-like Himantura polylepis belongs to ovoviviparous fish. Embryos develop in the womb, feeding on the yolk and histotroph. In the litter of 1–4 newborns with a disc about 30 cm wide. Pregnant females are often found in river estuaries, which are likely to serve as natural nurseries. In males, puberty occurs when a disc width of 1.1 m is reached [2] [5] .

Himantura polylepis generally does not show aggression, although they must be handled with care, since their poisonous long spike can pierce the bone [10] . They are not the target fishing target, but as by-catch they fall into gillnets and traps [12] [15] . These slopes are considered to be difficult prey: even fish caught on a hook can be difficult to pull out of the water, since they are often buried in the thickness of the silt [10] . Use meat and cartilage. Large individuals are sold by chopping into pieces [1] . Despite the fact that the meat of adult stingrays is not used for food, they are killed or maimed [15] . These stingrays are appreciated by amateur fishermen; they are kept in public aquariums. Unfortunately, this trend does not contribute to the preservation of the species, since they do not survive very well in captivity or after being released after being captured [2] .

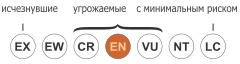

This species suffers greatly from environmental degradation caused by anthropogenic factors, in particular due to deforestation and land development. The construction of dams causes population divisions and impoverishes genetic diversity , which makes Himantura polylepis particularly vulnerable. Over the past 20-30 years, the number of these rays in the waters of Thailand and Cambodia has decreased by 30-50%, and in some areas by 95%. The size of the fish caught is getting smaller. For example, in Cambodia, the average catch weight fell from 23.2 kg in 1980 to 6.9 kg in 2006. In the 1990s, the Thai government launched an artificial breeding program for this species, but in 1996 it was suspended. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has assigned this species the status of “Endangered” [2] .

- Last, PR; Manjaji-Matsumoto, BM " Himantura dalyensis sp. nov., a new estuarine whipray (Myliobatoidei: Dasyatidae) from northern Australia. " In Last, PR; White, WT; Pogonoski, JJ Descriptions of new Australian Chondrichthyans. - CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research, 2008 .-- P. 283-292. - ISBN 0-1921424-1-0 .

- Last, PR; White, WT; Caire, JN; Dharmadi; Fahmi; Jensen, K .; Lim, APK; Mabel-Matsumoto, B .; Naylor, GJP; Pogonoski, JJ; Stevens, JD; Yearsley, GK Sharks and Rays of Borneo. - CSIRO Publishing, 2010. - P. 208–209. - ISBN 978-1-921605-59-8 .

- Monkolprasit, S .; Roberts, TR Himantura chaophraya , a new giant freshwater stingray from Thailand // Japanese Journal of Ichthyology. - 1990. - Vol. 37, No. (3) . - P. 203-208. Archived on October 20, 2013.

- ↑ 1 2 Himantura polylepis (English) in the FishBase database.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Himantura polylepis (English) . The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species .

- ↑ Bleeker, P. Bijdrage tot de kennis der Plagiostomen van den Indischen Archipel // Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen. - 1852. - Vol. 24. - P. 1-92.

- ↑ Great Ancient Greek Dictionary (Neopr.) . Date of treatment March 29, 2015. Archived February 12, 2013.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Monkolprasit, S .; Roberts, TR Himantura chaophraya , a new giant freshwater stingray from Thailand // Japanese Journal of Ichthyology. - 1990. - Vol. 37, No. (3) . - P. 203-208. Archived on October 20, 2013.

- ↑ Himantura polylepis (neopr.) . Shark References. Date of treatment March 30, 2015.

- ↑ 1 2 Last, PR; Manjaji-Matsumoto, BM " Himantura dalyensis sp. nov., a new estuarine whipray (Myliobatoidei: Dasyatidae) from northern Australia. " In Last, PR; White, WT; Pogonoski, JJ Descriptions of new Australian Chondrichthyans. - CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research, 2008 .-- P. 283-292. - ISBN 0-1921424-1-0 .

- ↑ Sezaki, K .; Begum, RA; Wongrat, P .; Srivastava, MP; SriKantha, S .; Kikuchi, K .; Shihara, H .; Tanaka, S .; Taniuchi, T .; Watabe, S. Molecular phylogeny of Asian freshwater and marine stingrays based on DNA nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the cytochrome b gene // Fisheries Biology. - 1999. - Vol. 65. - P. 563-570.

- ↑ Naylor GJP The phylogenetic relationships among requiem and hammerhead sharks: inferring phylogeny when thousands of equally most parsimonious trees result // Cladistics. - 1999. - Vol. 8, No. (4) . - P. 295-318. - DOI : 10.1111 / j.1096-0031.1992.tb00073.x .

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lovgren, S. Giant River Stingrays Found Near Thai City (neopr.) . National Geographic News. National Geographic Society (2008). Date of treatment April 1, 2015.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Last, PR and LJV Compagno. Myliobatiformes: Urolophidae ". In Carpenter, KE and VH Niem. FAO identification guide for fishery purposes: The living marine resources of the Western Central Pacific. - Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 1999. - P. 1479-1505. - ISBN 92-5-104302-7 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Last, PR; White, WT; Caire, JN; Dharmadi; Fahmi; Jensen, K .; Lim, APK; Mabel-Matsumoto, B .; Naylor, GJP; Pogonoski, JJ; Stevens, JD; Yearsley, GK Sharks and Rays of Borneo. - CSIRO Publishing, 2010. - P. 208–209. - ISBN 978-1-921605-59-8 .

- ↑ Fyler, CA; Caira, JN Five new species of Acanthobothrium (Tetraphyllidea: Onchobothriidae) from the freshwater stingray Himantura chaophraya (Batoidea: Dasyatidae) in Malaysian Borneo // Journal of Parasitology. - 2006. - Vol. 92, No. (1) . - P. 105-125. - DOI : 10.1645 / GE-3522.1 . - PMID 16629324 .

- ↑ Healy, CJ Three new species of Rhinebothrium (Cestoda: Tetraphyllidea) from the freshwater whipray, Himantura chaophraya, in Malaysian Borneo // Journal of Parasitology. - 2006. - Vol. 92, No. (2) . - P. 364-374. - DOI : 10.1645 / GE-560R.1 . - PMID 16729696 .

- ↑ 1 2 Fowler, SL, Cavanagh, RD, Camhi, M., Burgess, GH, Cailliet, GM, Fordham, SV, Simpfendorfer, CA and Musick, JA Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes. - International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 2005. - P. 338—349. - ISBN 2-8317-0700-5 .