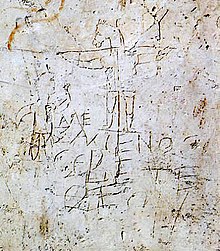

Aleksamenos graffiti (also known as Blasphemous graffiti [1] ) is a graffiti -style picture carved on a gypsum wall near the Palatine Hill in Rome , now in the Palatine Antiquarian Museum. It is considered one of the first artistic images of the crucified Jesus Christ (along with several gems [2] ).

Description

The graffiti depicts a humanoid figure crucified on a cross with the head of an ass . In the upper right corner of the image is a symbol, defined either as the Greek letter epsilon, or as a tau cross [1] . In the left part of the image, a young man, apparently representing Aleksamenos [3] , a Roman soldier or guard, raises one hand in a gesture that presumably involves the worship of this figure [4] [5] . Under the cross there is an inscription written in broken Greek: "Αλεξαμενος ςεβετε θεον". The word “ςεβετε” here can be interpreted as a spelling variant (perhaps phonetically erroneous [6] ) of the word “εβεται” in traditional Greek, meaning “worship”. Fully inscription in the end can be translated as "Aleksameno worships [his] god" [6] [7] [8] . Some other sources offer as a supposed translation the option “Aleksamenos in the process of worshiping God” or similar [9] [10] [11] [12] .

Dating

There is no clear consensus on when the drawing was created. Assumptions were made about the period from the end of the first century to the end of the third century [13] , while the beginning of the third century is believed to be most likely in terms of the time of its creation [7] [14] [15] .

Discovery and location

Graffiti was discovered in 1857, when a building called Domus Gelotiana was discovered on the Palatine Hill. Emperor Caligula purchased this house for the imperial palace there, which after the death of Caligula was used as a pedagogy (boarding school) for the imperial pages. Later, the street on which the building was located was fenced off in order to expand the area of the surrounding buildings, and the building thus remained closed for centuries [16] . Nowadays, graffiti is placed in the Antiquarian Palatine in Rome [6] .

Interpretation

The inscription is considered by authoritative sources, such as the Catholic Encyclopedia [17] , as a caricature depicting a Christian in the act of worship. Images of both the donkey’s head and the crucifix were considered offensive by the then Roman society. Crucifixion continued to be practiced as a method of execution for the most notorious criminals until its abolition by the emperor Constantine in the 4th century, and the impact that a crucifix pattern could have been on was comparable to the impact that today can be a picture of a man with a hanging hanger around his neck or sitting in the electric chair [18] .

It is assumed that at that time it was assumed that Christians practice onolatry (worship of an ass). This was based on the delusion that the Jews worshiped God in the form of a donkey, a delusion of unknown origin. Tertullian, who wrote at the end of the second or early part of the third century, reports that Christians, along with Jews, were accused of worshiping such a deity. He also mentions a Jewish cross , who painted a caricature of a Christian with donkey’s ears and hooves in Carthage called Deus Christianorum Onocoetes (“The God of Christians born of a donkey”) [19] .

According to other assumptions, the graffito depicts the worship of the Egyptian gods Anubis [8] or Seth [20] ; or the young man participates in the gnostic ceremony with the participation of a figure with a horse's head, while in the upper right corner of the crucified figure there is not a Greek letter epsilon, but a tau cross [1] .

There is also an assumption that both graffiti and gems created around the same time with the image of a crucifix are associated with heretical extrachurch groups of the time [21] .

Value

To date, there are disputes about whether the worship of the crucifix depicted on graffiti was practiced by modern Christians, or whether the donkey's head was added to the image solely for the sake of ridiculing Christian beliefs. It was argued that the alleged presence of a loincloth on a crucified figure, which differed from the traditional Roman execution procedure, in which the convict was completely naked, proves that the artist had to rely on Alexamenos worship or other worship when creating his drawing [22 ] . However, an opinion was also expressed against such an approach, based on the fact that the cross was not actually used in Christian worship before the 4th and 5th centuries [23] .

Alexamenos Fidelis

In the next room of the building, another inscription was found, made by another hand and read as “Alexamenos Fidelis”, which in Latin means “Aleksamo ny true” or “Aleksamo ny true” [24] . This inscription may be the answer of an unknown Christian to the mocking caricature of Aleksamenos, presented in graffiti [15] .

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 3 Bayley, Harold. Archaic England: An essay in deciphering prehistory from megalithic monuments, earthworks, customs, coins, place-names, and faerie superstitions . - Chapman & Hall, 1920.

- ↑ Schiller, 89-90, fig. 321

- ↑ Rodolfo Lanciani, 1898, chapter 5 'The Palace of the Caesars'

- ↑ Thomas Wright, Frederick William Fairholt, A History of Caricature and Grotesque in Literature and Art , Chatto and Windus, 1875, p. 39

- ↑ Augustus John Cuthbert Hare, Walks in Rome, Volume 1 , Adamant Media Corporation, 2005, p. 201

- 2 1 2 3 Rodney J. Decker, The Alexamenos Graffito

- 2 1 2 David L. Balch, Carolyn Osiek, Early Christian Families in Context: An Interdisciplinary Dialogue , Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003, p. 103

- 2 1 2 down down down down down down,,,,,, University of Michigan Press, 2002, p. 208

- ↑ The Ass (in Caricature of Christian Beliefs and Practices)

- ↑ Home Page - Concordia Theological Seminary . Ctsfw.edu The date of circulation is October 17, 2012. Archived July 4, 2008.

- ↑ A Sociological Analysis of Graffiti . Sustain.ubc.ca. Circulation date October 17, 2012. Archived October 4, 2011.

- ↑ Charles William King. Gnostics and their Remains (1887). The appeal date is October 17, 2012.

- ↑ Hans Schwarz, Christology , Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1998, p. 207

- ↑ Schiller, 90

- ↑ 1 2 Michael Green, Evangelism in the Early Church , Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, p. 244

- ↑ Edward L Cutts, History of Early Christian Art , Kessinger Publishing, 2004, p. 200

- ↑ Drum, Walter . The Incarnation.

- ↑ NT Wright , for What Saint Paul for Really Said: Was Paul of Tarsus the Real Founder of Christianity? , 1997, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, p. 46

- ↑ Tertullian , Ad nationes , 1:11, 1:14

- ↑ Hasset, Maurice M .. The Ass (in Caricature of Christian Beliefs and Practices). . “Wünsch, however, it’s possible to make it possible to constitute an assortment of Typhon-Seth (Bréhier, Les origines du crucifix , 15 sqq.). But the reasons for this hypothesis are not convincing. ”

- ↑ Schiller, 89-90

- ↑ Marucchi, Orazio; Cabrol, Fernand & Thurston, Herbert . Cross and Crucifix.

- L. David L. Balch, Carolyn Osiek, Early Christian Families in Context: An Interdisciplinary Dialogue , Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003, p. 103, footnote 83

- ↑ Hassett, Maurice M .. Graffiti.

Bibliography

- Schiller, Gertrud. Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II , 1972 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0-85331-324-5 .