Voronezh Fortress - a military fortress of the Russian kingdom , built in 1586 on the banks of the Voronezh River to protect the southern territories from Tatars raids, as well as to counter the advance to the north of the Cherkasy . It gave rise to the city of Voronezh . Lost its significance by the end of the XVII century.

Content

Description

Fortress location

Studies by historians V.P. Zagorovsky and Popov suggest that the Voronezh fortress was located on a hill behind Voronezh State University [1] . The area of its deployment is now limited by the streets of Frunze, Shevchenko, Belinsky and Sevastyanovsky (Ilyinsky) congresses.

Chopped City and Ostrog

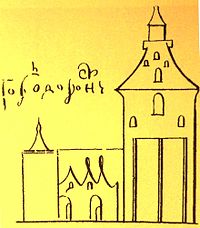

According to the preserved Patrol Book of 1615, written by Moscow officials under the leadership of G. Kireevsky, the Voronezh fortress had two separate fortification belts. The inner one was called the “chopped city” (in other similar fortresses it was called the Kremlin), and the outer one was called the “prison”.

The “chopped-down city” or simply “the city” (after 1670 it became known as the “small city”) was surrounded by three towers (Moscow, Zatinnaya and Tainitskaya), connected by walls, which were united log cabins, covered with earth. Its area was a little more than 4,000 m², and the perimeter was 300 m. On the territory of the “city” there were “moving huts” (voivode office), a cathedral church and premises for storing grain, gunpowder and weapons.

Ostrog (after 1670 it was called the "big city") covered the "city" from the west and north, and was located on the territory of modern University Square. It was a fortification of towers connected by walls. The walls were logs vertically dug into the ground. Among the towers there were 7 passers-by with gates, and the rest were deaf. According to the most authoritative sources [1] [2], the total number of towers was 25. Nevertheless, in 2011, in one of the articles of the architectural magazine [3] , devoted to the history of the Voronezh fortress, it was suggested that the total number of towers in the “prison” could be and 18, among which 7 are passers-by and 11 are deaf. After the reconstruction in 1670, the number of towers was reduced to 17.

According to the surviving plan of the 1670 fortress, the bishop’s yard of the Voronezh diocese , the Annunciation Cathedral and 5 more churches were located on its territory.

Caches (underground passages to the river)

An important element of the fortress was hiding places - underground passages leading to the river. They were designed to provide water to the defenders of the fortress in the event of a siege. The first hiding place, built together with the fortress, went from the “chopped city” to the well by the river. In the sources of 1650 this move is called already old. A new cache was dug in the 1630s from the Tainitskaya tower. Its length was 136 meters, width - 3.3 meters, and height - more than 2 m. Then a new cache was abandoned, but in 1669 it was restored. After 1680, the caches ceased to be maintained.

Armament

According to the report to Moscow [4] , written by the Voronezh governor in 1678, there were 12 iron and 12 copper cannons on the walls and towers of the Voronezh fortress.

History

The decision to start its construction was made in a hurry because of the difficult military-political situation. Therefore, all the basic initial work was carried out in the winter, which was uncharacteristic for that time. Typically, fortresses in the Russian state were built in the summer and autumn after the adoption of the relevant decree.

The place of the future fortress, most likely, was chosen by Vasily Birkin and Ivan Sudakov-Myasny, who later became the mayors of Voronezh. The fortress was built under the leadership of Moscow nobleman S.F. Papin-Saburov , the first Voronezh governor.

In 1586, construction work was completed [5] . In 1587, 8 “neighbors” and 4 “distant” watchmen were exhibited around her.

In 1590, a detachment of Cherkas [5] , who served the Polish king, arrived at the Voronezh fortress. They expressed their desire to fight with the Russians against the Tatars. Given that peace was concluded between the Russian kingdom and Lithuanian-Polish, the Voronezh governor let them in and allowed them to spend the night on the territory of the prison. At night, the Cherkasy attacked the service people, killed the governor and burned the fortress.

In 1592 and 1594, Russian embassies were sent to the Ottoman Empire [6] . In 1592, the embassy was headed by Grigory Nashchekin. The Voronezh Cossacks met the ambassador and his guards at the mouth of the Voronezh River and proceeded with them until the Tsimly River flowed into the Don. In 1594, the Russian embassy first proceeded through Voronezh. The Voronezh voivode should have been provided with protection and separate river plows for walking along the Voronezh and Don rivers. Later in the XVII century, the path of the Russian and Turkish embassies constantly ran through the Voronezh fortress.

New Russian fortresses were built in the west of Voronezh in 1596: Belgorod and Oskol (the modern name is Stary Oskol) [6] . Their watchmen were exposed considering Voronezh; interaction was established between them.

In the winter of 1617, Cherkessians numbering 5,000 people "began to attack the city and the prison twice from all sides with brutal attacks." The fortress was able to protect. After the retreat, Cherkess was chased by 10 miles. In 1630, they were expected to attack again in the Voronezh fortress (a new hiding place had been dug up by that time - an underground passage to the river), but the Cherkasy never appeared. The threat of the invasion of the Tatars remained real. So in August 1643, more than 1,000 Tatars attacked the villages of Bobyakovo, Borovoye, Stupino, etc., and then breaking through the fortifications on the left bank of the Voronezh River opposite the Voronezh fortress, crossed the right bank and attacked the Chizhovka settlement. In 1658, the Tatars captured 21 people in the village of Repnoye and the village of Pridacha. After 1659, the attacks of the Tatars and Cherkas ceased, since a defensive line of fortifications, the Belgorod line, was built on their way.

In 1670, the fortress was rebuilt, led by the governor B. G. Bukhvostov. The number of towers was reduced to 17. The territory was increased. Since in 1682 Voronezh became the center of the Voronezh diocese, a bishop’s yard and a new stone Annunciation Cathedral were built inside the fortress.

Around 1696, the Voronezh fortress lost its significance as well as other fortresses of the Belgorod line . In the notes of the Dutch traveler Cornelius de Bruyne in 1703, it is noted that its walls have already decayed. Voronezh ceased to be a military fortress and began to develop first as a shipbuilding center for the Azov fleet , and then as a provincial city.

Service People and Population

Service in the fortress was carried out by service people who, usually, were not paid state salaries. Using the land allocated to them, they were engaged in agriculture. Posad people (craftsmen, traders, etc.), church and monastery people also lived on the territory of the fortress and in the nearby settlements. The Voronezh fortress, like other Russian fortresses of that time, was governed by the governor.

Governors

- from 1585 to 1585 - Semyon Fedorovich Papin-Saburov

- from 1586/1587 to ??? year - Fedor Mikhailovich Paskirev

- Grigory Petrovich Romodanovsky

- Ivan Andreevich Dolgoruky

- Prince Grigory Ivanovich Dolgoruky (nicknamed the Devil)

- Prince Vladimir Ivanovich Klobukov-Mosalsky

Service people

According to the list [7] , compiled in 1636, there were 681 servicemen in the Voronezh fortress:

- horse regimental Cossacks (310 people),

- foot archers (200 people),

- white-breasted atamans and Cossacks (105 people),

- Pushkari (22 people),

- zatinschiki (25 people serving the "quiet peepers" - small-caliber guns),

- thief about tniki (7 people guarding the castle gates)

- blacksmiths (2 people),

- coachmen (10 people)

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 Komolov N.A. The city of Voronezh: the history of the ancient fortress and adjacent streets from the base to the General Plan of Catherine II .

- ↑ Zagorovsky V.P. Voronezh: a historical chronicle, 1989 .

- ↑ Grandfathers. Part 1, 2011 .

- ↑ Zagorovsky V.P. Voronezh: a historical chronicle, 1989 , p. 36.

- ↑ 1 2 Zagorovsky V.P. Voronezh: historical chronicle, 1989 , p. 16.

- ↑ 1 2 Zagorovsky V.P. Voronezh: historical chronicle, 1989 , p. 17.

- ↑ Zagorovsky V.P. Voronezh: a historical chronicle, 1989 , p. 24.

Literature

- Abbasov A.M. Voronezh fortress and its first builders // Notes of the Voronezh local historians. - Voronezh, 1987 .-- 130-155 p.

- Voronezh in documents and materials / Ed. V.V. Kulinova, V.P. Zagorovsky. - Voronezh: Center.-Chernozem. Prince Publishing House, 1987 .-- 272 p.

- Voronezh Encyclopedia . - Reference and encyclopedic publication. - Voronezh: Center for the Spiritual Revival of the Black Earth Region, 2008. - T. 1 (A – M). - 524 s. - ISBN 978-5-900270-99-9 . . The publication was made by decision of the administration of the Voronezh region

- Voronezh Encyclopedia. - Reference and encyclopedic publication. - Voronezh: Center for the Spiritual Revival of the Black Earth Region, 2008. - T. 2 (NY). - 524 s.

- Zagorovsky V.P. Voronezh: a historical chronicle. - Local history publication. - Voronezh: Central Black Earth Book Publishing House, 1989. - 255 p. - ISBN 5-7458-0076-3 .

- Komolov N.A. The city of Voronezh: the history of the ancient fortress and adjacent streets from the base to the General Plan of Catherine II (Doc). The site of the administration of the city district of Voronezh. Date of treatment July 14, 2014.

- Panova V.I. History of the Voronezh region. - 4th, add. - Voronezh: “Native speech”, 2008. - 287 p. - ISBN 978-5-8745-6562-6 . . The book is a laureate of regional competitions in textbooks and teaching aids in 1994 and 1995

- Dedov A. Town-planning chronicles of medieval Voronezh. Architectural and historical investigation. Part 1. . Magazine "Front quarter" (01/11/2011). Date of treatment July 14, 2014.

- Dedov A. Town-planning chronicles of medieval Voronezh. Architectural and historical investigation. Part 2. . The magazine "Front quarter" (02/07/2011). Date of treatment July 14, 2014.

- Dedov A. Town-planning chronicles of medieval Voronezh. Architectural and historical investigation. Part 3. . The magazine "Front quarter" (03/09/2011). Date of treatment July 14, 2014.