A simple number is a natural (positive integer) number that has exactly two different natural dividers — the unit and itself [1] . In other words, the number is simple if it is bigger and at the same time is divided without remainder only and on . For example, Is a prime number is a composite number, because, besides and also divided by and on .

The basic theorem of arithmetic establishes the central role of primes in the theory of numbers : any integer greater than , or is simple, or can be expressed as a product of primes, and this expression is unique up to the order of factors. To ensure uniqueness in this theorem, one is not considered a prime number (otherwise, one can include arbitrarily many units in any decomposition [2] , for example, etc.).

Natural numbers that are greater than one and are not simple are called composite . Thus, all natural numbers are divided into three classes: one (having one natural divisor), prime numbers (having two natural dividers), and composite numbers (having more than two natural dividers) [1] . The theory of numbers deals with the study of the properties of primes. Both simple and composite numbers are infinitely many.

The sequence of primes starts like this:

- 2 , 3 , 5 , 7 , 11 , 13 , 17 , 19 , 23 , 29 , 31 , 37 , 41 , 43 , 47 , 53 , 59 , 61 , 67 , 71 , 73 , 79 , 83 , 89 , 97 , 101 , 103 , 107 , 109 , 113 , 127 , 131 , 137 , 139 , 149 , 151 , 157 , 163 , 167 , 173 , 179 , 181 , 191 , 193 , 197 , 199 ... [3]

The property of being simple is called simplicity. A simple but slow method of checking the simplicity of a given number n is known as enumerating divisors ; more efficient algorithms are described below .

Many problems concerning primes remain open, see below .

Prime numbers are widely used in mathematics and related sciences - for example, in many information technology algorithms, such as a public-key cryptosystem , which uses properties such as the complexity of decomposing numbers into prime factors [4] .

There are generalizations of the concept of a prime number for arbitrary rings and other algebraic structures, see below .

Content

History

It is not known when the notion of a prime number was defined, however, the first evidence of the understanding of such numbers belong to the Upper Paleolithic, which is confirmed by the bone Ishango . [five]

In the preserved records of the ancient Egyptians there are hints that they had some information about prime numbers: for example, Reind's papyrus, dating back to the 2nd millennium BC. er contains a table expressing fractions of the form 2 / n in terms of the sum of two, three or four fractions with numerators equal to one and different denominators. Decompositions of fractions, the denominators of which have a common divisor, are similar, which suggests that the Egyptians at least knew the difference between a prime number and a composite number [6] .

However, the earliest surviving studies of primes come from the ancient Greeks . Euclidean principles (about 300 BC) contain important theorems on primes, including the infinity of primes, the Euclidean lemma, and the main theorem of arithmetic [7] . In ancient Greece, the sieve of Eratosthenes was also invented, a simple algorithm for finding all prime numbers from 1 to n.

After the Greeks, little happened in the study of primes until the seventeenth century [8] . In 1640, Pierre de Fermat formulated (without proof) the small Fermat theorem (later proved by Leibniz and Euler ) and the theorem on the sum of two squares . Fermat also suggested that all numbers of the form + 1 are simple (they were called Fermat numbers ) and proved it up to n = 4 (or + 1). However, Euler showed that already the next Fermat number with n = 5 (or + 1) is compound (divided by the number 641). To date, there are no other known Farm numbers that are simple. At the same time, the French monk Maren Mersenne drew attention to primes of the form 2 p - 1, where p is a prime (not all numbers of this kind are prime). [9] They were called Mersenn primes in his honor.

Euler's work in number theory included a lot of information about primes. He showed that the infinite series 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/5 + 1/7 + 1/11 + ... is divergent. Also in 1747, he showed that even perfect numbers are integers of the form where the second multiplier is a simple mersenne. In Euler's correspondence with Christian Goldbach, the latter formulated the famous Goldbach conjecture on the representation of any even number, starting with 4, as the sum of two simple, which has not yet been proved. [ten]

Since the beginning of the XIX century, the attention of many mathematicians turned to the study of the asymptotic distribution of primes. [10] Legendre and Gauss independently suggested that the density of prime numbers is on average close to the inverse of the natural logarithm . [eleven]

For a long time, primes were considered to have limited use outside of pure mathematics . The situation changed in the 1970s, when the concepts of public-key cryptography appeared , in which simple numbers formed the basis of the first algorithms, such as the RSA encryption algorithm [12] .

Decomposition of natural numbers in the product of simple

The representation of a natural number in the form of a product of simple is called the decomposition into simple or factorization of a number . At present, polynomial number factorization algorithms are unknown, although it has not been proven that there are no such algorithms. The cryptosystem RSA and some others are based on the assumed large computational complexity of the factorization task. Factorization with polynomial complexity is theoretically possible on a quantum computer using the Shor algorithm [13] .

The basic theorem of arithmetic

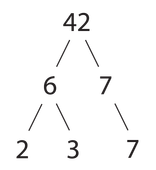

The main theorem of arithmetic asserts that every natural number greater than one is representable as a product of prime numbers, and in a unique way up to the order of the factors. [14] Thus, primes are the elementary "building blocks" of natural numbers. For example:

. ( denotes square or second degree .)

As shown in this example, the same simple divider can appear several times. Decomposition:

- n = p 1 · p 2 · ... · p t

the numbers n into (finite) prime factors p 1 , p 2 , ..., p t is called the prime factorization of the number n . The basic theorem of arithmetic can be rephrased in this way: any decomposition into prime numbers will be identical, except for the order of divisors . In practice, for most numbers there are many simple factorization algorithms, all of which give the same result. [13]

If p is a prime number and p divides the product of ab integers, then p divides a or p divides b . This sentence is known as the Euclidean Lemma . [15] It is used in some evidence of the uniqueness of factorization.

Simplicity of unit

Most ancient Greeks did not even consider number, so they could not consider it simple. [16] By the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, many mathematicians included as the first prime number. [17] In the middle of the 18th century, Christian Goldbach listed as the first prime in his famous correspondence with Leonard Euler ; however, Euler himself did not consider prime number. [18] In the XIX century, many mathematicians still considered the number prime number. For example, Derrick Norman Lemer’s list of simple numbers to numbers, reprinted in 1956, began with as the first prime number. It is said that Henri Lebesgue is the last mathematician who called simple [19] By the beginning of the 20th century, mathematicians began to arrive at a consensus that is not a prime number, but rather forms its own special category - “unit”. [17]

If you count prime number, then the Euclidean basic arithmetic theorem (mentioned above) will not be fulfilled as indicated. For example, the number can be decomposed as 3 · 5 and 1 · 3 · 5 . If is a prime number, these two options would be considered as different factorizations. therefore the statement of this theorem would have to be changed. [17] Likewise, the Eratosthenen sieve would work incorrectly if was considered simple: a modified version of the sieve, which assumes that is a prime number, excludes all multiples (that is, all the other numbers) and gives only one number at the output - . In addition, prime numbers have several properties that the number does not have. such as the ratio of the number to its corresponding value of the Euler identity function or the sum of the divisor function . [2]

Algorithms for searching and recognizing prime numbers

Simple ways of finding the initial list of primes up to a certain value are given by the sieve of Eratosthenes , by Sundaram ’s sieve and Atkin’s sieve . [20]

However, in practice, instead of obtaining a list of prime numbers, it is often necessary to check whether a given number is simple. Algorithms that solve this problem are called simplicity tests . There are many polynomial tests of simplicity, but most of them are probabilistic (for example, the Miller – Rabin test ) and are used for cryptography . [21] In 2002, it was proved that the problem of checking for simplicity is generally polynomially solvable, but the proposed deterministic Agraval – Kayal – Saxen test has a rather large computational complexity , which makes its practical application difficult. [22]

For some classes of numbers, there are specialized effective simplicity tests (see below).

Simplicity Test

A test of simplicity (or a test of simplicity) is an algorithm that, having accepted a number as input, either allows you not to confirm the assumption that the number is composite , or to state its simplicity precisely. In the second case, it is called the true test of simplicity. The simplicity test task belongs to the complexity class P , that is, the running time of its solution algorithms depends on the size of the input data polynomially, which was proved in 2002 . [23]

The existing algorithms for checking the number for simplicity can be divided into two categories: true tests of simplicity and probabilistic tests of simplicity. The result of computing true tests is always a fact of simplicity or a composite number. A probabilistic test shows whether a number is simple with a certain probability. Numbers that satisfy the probabilistic simplicity test, but are composite, are called pseudoprime . [24] One example of such numbers is Carmichael numbers . [25]

One example of true simplicity tests is the Luke-Lemere test for Mersenne numbers . The obvious disadvantage of this test is its applicability only to numbers of a certain type. Other examples include Fermat's small theorem [26]

- Pepin test for Farm numbers

- Prot's theorem for Prot numbers

- Agraval-Kayal-Saxony test , the first universal, polynomial, deterministic and unconditional simplicity test.

- Test of Luke - Lemera - Rizel

And:

- divider search method

- Wilson's theorem

- Pocklington test

- Miller's test

- The Adleman-Pomerans-Rumeli test , improved by [27] Cohen and Lenstroy

- A simplicity test using elliptic curves .

The probabilistic tests of simplicity include:

- Farm test

- Miller's test - Rabin

- Test Nightingale - Strassen

- Test Bailey - Pomeranza - Selfridge - Wogstaff

Large prime numbers

For centuries, the search for "large" prime numbers has attracted the interest of mathematicians. In recent decades, these studies have acquired practical significance due to the use of such numbers in a number of encryption algorithms, such as RSA [12] .

In the seventeenth century, Marin Mersenne suggested that the numbers of the species simple (with n ≤ 257) only for n equal to 2, 3, 5, 7, 13, 19, 31, 67, 127 and 257. [11] Testing the correctness of the assumption was much higher than the possibilities of that time. It was only in the 20th century that it was discovered that the hypothesis was false and probably made “blindly”, since Mersenne did not take into account three cases (for n = 61, 89 and 107); in addition, it turned out that the numbers corresponding to n = 67 and n = 257 are composite. [eleven]

In 1876, Edward Luke proved that the number M 127 (39-digit number) is simple, it remained the largest known prime number until 1951, when (44 digits) and, a little later, (from 79 digits) - the last prime number that was found using an electronic calculator. Since then, all subsequent large prime numbers were discovered using a computer: since 1952 (when SWAC showed that the M 521 is simple), until 1996 they were found by a supercomputer , and all were simple Mersenne (found using the Luke-Lemere test specific algorithm for such numbers), except for the number which was a record between 1989 and 1992. [28]

Algorithms for obtaining prime numbers

Some math problems using factorization require a series of very large primes selected at random. The algorithm for their production, based on Bertrand's postulate (For any natural n ≥ 2 there is a prime number p in the interval n < p <2 n .): [29]

Algorithm:

|

The time to solve the problem by this algorithm is not defined, but there is a high probability that it is always polynomial, as long as there are sufficiently simple numbers and they are distributed more or less evenly . For simple random numbers, these conditions are satisfied. [22]

The most effective means of constructing prime numbers is the slightly modified Fermat's small theorem . [27]

Let N, S be odd natural numbers, N-1 = S * R, and for each prime divider q number S there is an integer such that

,

Then each prime divider p of the number N satisfies the comparison

The investigation. If the conditions of the Fermat theorem and , then N is a prime number. [27]

We now show how using the last assertion, having a large prime number , it is possible to construct a substantially larger prime number . We choose for this randomly even number on the gap and put . Then check the number the absence of small prime factors, dividing it into small prime numbers; will test a number of times using the Rabin algorithm. If it turns out that - composite number, select a new value and repeat the calculation again. This should be done until a number N is found that has stood the test of the Rabin algorithm quite a few times. In this case, there is hope that - a prime number, and one should try to prove simplicity with the help of simplicity tests. [27]

The infinity of the set of primes

There are infinite primes. This statement is referred to as the Euclidean theorem in honor of the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid , since the first known proof of this statement is attributed to him. There are many more proofs of the infinity of primes, including Euler’s analytic proof, Goldbach’s proof based on Fermat’s numbers , [30] Furstenberg’s proof using general topology, and Kummer’s elegant proof.

The greatest known simple

Records marking the greatest numbers known at that time have been kept for a long time [31] . One of the records set in his time Euler , finding a prime number 2 31 - 1 = 2 147 483 647 .

The largest known prime number as of January 2019 is the Mersenne number M 82 589 933 = 2 82 589 933 - 1 . It contains 24,862,048 decimal digits ; in a book with a record of this number would be about nine thousand pages. It was found on December 7, 2018 as part of the GIMPS distributed Mersenn prime numbers project . The previous largest known prime number, opened in December 2017, was 1,612,623 less [32] .

Mersenne's numbers compare favorably with the rest by the presence of an effective simplicity test : the Luke-Lemer test . Thanks to him, Mersenne prime numbers have long held the record as the largest known simple ones.

For finding prime numbers from more than 100,000,000 and 1,000,000,000 decimal digits, the EFF has assigned [33] cash prizes of $ 150,000 and $ 250,000, respectively [34] . The EFF has already awarded prizes for finding prime numbers of 1,000,000 and 10,000,000 decimal digits.

Special type

There are a number of numbers, the simplicity of which can be established efficiently using specialized algorithms.

- Mersenne numbers - numbers of the form where n is a natural number [35] . Moreover, the Mersenne number can be simple only if n is a prime number. As noted above, an effective test of simplicity is the Luke-Lemere test [36] .

- Farm numbers - numbers of the form where n is a non-negative integer [37] . An effective test of simplicity is the Pepin test . As of February 2015, only 5 prime numbers of the Farm are known (for n = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4), twenty eight of the following numbers of the Farm (up to inclusively) turned out to be composite [38] , but it has not been proven that there are no other Fermat primes [39] .

- Woodal numbers - numbers of the form [40] . An effective test of simplicity is the Luke-Lemer-Rizel test [41] .

- Cullen numbers - numbers of the form [42] [43] .

- Prota Numbers - numbers of the form with k being odd and [44] . An effective test of simplicity for Prot numbers is the Brillhart – Lemer – Selfridge test (the Brillhart – Lehmer – Selfridge test ) [45] . Cullen numbers and Fermat numbers are a special case of Prot numbers (respectively, with k = n and with k = 1, ) [46] .

- Mills numbers - numbers of the form Where - Mills constant . [47]

For the search for prime numbers of the types indicated, the projects of distributed computing GIMPS , PrimeGrid , Ramsey @ Home , Seventeen or Bust , Riesel Sieve , Wieferich @ Home are currently used.

Some properties

- If p is simple and p divides ab , then p divides a or b . The proof of this fact was given by Euclid and is known as the Euclidean lemma [7] . It is used in the proof of the main theorem of arithmetic .

- Deduction ring is a field if and only if - simple [48] .

- The characteristic of each field is zero or a prime number [48] .

- If a - simple, but - natural, then divided by ( Fermat's small theorem ) [49] .

- If a - finite group, the order of which divided by then contains an element of order ( Cauchy's theorem ) [50] .

- If a - final group, and - maximum degree which divides then has a subgroup of order , called the Sylow subgroup , moreover, the number of Sylow subgroups is equal to for some whole ( Sylow's theorems ) [51] .

- Natural is simple if and only if divided by ( Wilson's theorem ) [52] .

- If a - natural, then there is a simple such that ( Bertrand's postulate ) [53] .

- A number of inverse of simple numbers diverges [10] . Moreover, with

- Any arithmetic type progression where - mutually simple integers , contains infinitely many primes ( Dirichlet's prime numbers theorem in an arithmetic progression ) [54] .

- Any prime number greater than 3 is representable as or where - some natural number. Hence, if the difference between several consecutive primes (for k> 1) is the same, then it is necessarily a multiple of 6 — for example: 251-257-263-269; 199-211-223; 20183-20201-20219.

- If a - simple, then multiple of 24 (also true for all odd numbers that are not divisible by 3) [55] .

- Green-Tao theorem . There are arbitrarily long finite arithmetic progression consisting of prime numbers [56] .

- No prime number can be where n > 2, k > 1. In other words, the number following a prime cannot be a square or higher degree with a base greater than 2. It also follows from this that if a prime number has the form , then k is a prime (see Mersenne numbers ) [35] .

- No prime number can be where n > 1, k > 0. In other words, a number preceding a simple one cannot be a cube or a higher odd degree with a base greater than 1 [57] .

- Each prime number (except for the numbers of the form 8n-1) can be represented as the sum of three squares [58] .

Applications

Prime numbers are fundamental components in many areas of mathematics .

Arithmetic functions

Arithmetic functions , namely, functions defined on the set of natural numbers and taking values in the set of complex numbers, play a decisive role in number theory. In particular, among them the most important are multiplicative functions, i.e. functions having the following property: if a couple consists of mutually simple numbers, then equality takes place [59]

Examples of multiplicative functions are the Euler function. which matches the number the number of positive integers less than n and mutually simple with it and the number of divisors of the number n . [60] The value of these functions on the degree of a prime number:

- Function Euler:

- Divider function :

{\ displaystyle \ sigma (p ^ {m}) = m + 1}

Arithmetic functions can be easily calculated by knowing the values they take for powers of primes. [59] In fact, from the decomposition of a natural number into factors

we have that

and therefore, returning to the problem of computing it turns out what to calculate from each power of a simple divider is usually simpler than calculating according to the general formula. [61]

For example, to find out the meaning of the Euler function from n = 450 = 2 × 3 2 × 5 2 , it suffices to calculate

Modular arithmetic

In modular arithmetic, primes play a very important role: the residue ring is a field if and only if n is simple. [48] Also the existence of a primitive ring root. is bound to prime numbers: it exists only if n is a prime number, 1, 2, 4 or a number in the form where p is odd.

One of the most important theorems of modular arithmetic is the small Fermat theorem . [52] This theorem states that for any prime number p and any natural number a we have:

or for any simple p and any natural, but not divisible by p , holds true:

This property can be used to verify that the number is not prime. In fact, if n is such that:

for some natural a , then n cannot be simple. [52] However, this property cannot be used to check the number for simplicity: there are some numbers, called Carmichael numbers (the smallest is 561) for which this will be wrong. A Carmichael number is a composite number that is a pseudo-prime number for each base b that is mutually prime with n. In 1994, William Robert Alford, Andrew Granville and Karl Pomerance showed that there are infinitely many such numbers. [62]

Group Theory

Prime numbers also play a fundamental role in algebra . In group theory , a group in which each element is a power of a prime p is called a p-group [63] . A P-group is finite if and only if the order of the group (the number of its elements) is a power of p. An example of an infinite p-group is the Prüfer p- group [64] . It is known that p- groups have a non-trivial center and, therefore, cannot be simple (except for the group with p elements); if the group is finite, moreover, all normal subgroups intersect the center in a non-trivial way.

An example of such groups is the cyclic multiplication group modulo a prime number [65] .

All groups of order p are cyclic and therefore abelian ; also abelian each group of order p 2 . In addition, any finite Abelian group is isomorphic to a direct product of a finite number of cyclic p-groups.

The Cauchy theorem states that if the order of a finite group G is divisible by a prime number p, then G contains elements of order p. This theorem is generalized by Sylow's theorems [50] .

Public Key Cryptosystem

Some public-key cryptography algorithms, such as RSA and Diffie-Hellman key exchange , are based on large primes (usually 1024-2048 bits). RSA relies on the assumption that it is much easier (that is, more efficient) to multiply two (large) numbers x and y than to calculate mutually simple x and y if only their product is known . Diffie-Hellman key exchange is based on the fact that there are effective modular exponentiation algorithms, and the inverse operation of discrete logarithmization is considered complex. [66] [67]

RSA

The difficulty of factoring large numbers led to the development of the first effective public key cryptography method - RSA . [68] In this cryptographic system, the person who is to receive the encrypted message generates a key: two different random primes are selected. and specified size (usually used, 1024- or 2048- bit numbers). Further their product is calculated called a module . Calculates the value of the Euler function of the number : . An integer is selected. ( ), mutually simple with the function value . Usually as take small primes (for example, Fermat primes). Number is called an open exponent ( eng. public exponent ). Calculates the number , called the secret exponent, multiplicatively inverse to the number e modulo . Couple It is published as an RSA public key ( RSA public key ). Couple plays the role of the private key RSA ( English RSA private key ) and is kept secret. [12]

Theoretically, you can get the private key from publicly available information: currently, this requires factoring the number , which makes sending a secure message safe if primes satisfy certain conditions and are “big enough”. It is not yet known whether there are effective methods for decrypting a message not related to a direct attack on factorization. but it has been shown that poor public key selection can make the system more vulnerable to such attacks. [69]

In 1991, RSA Security published a list of semi-simple numbers, offering cash prizes for decomposing some of them into factors, in order to confirm the safety of the method and encourage research in this area: the initiative was called RSA Factoring Challenge . [70] Over the years, some of these numbers have been decomposed, while for others the problem of factorization is still open; however, the competition was completed in 2007. [70]

Formulas for finding prime numbers

At different times, attempts were made to specify an expression whose values for different values of the variables contained in it would be prime numbers [54] . L. Euler indicated a polynomial taking simple values at n = 0, 1, 2, ..., 40 . However, for n = 41 , the polynomial value is a composite number. It can be proved that there is no polynomial in one variable n , which takes simple values for all integer n [54] . P. Fermat suggested that all numbers of the form 2 2 k + 1 are simple; however, Euler refuted this hypothesis, proving that the number 2 2 5 + 1 = 4,294,967,297 is composite [54] .

Nevertheless, there are polynomials whose set of positive values for non-negative values of variables coincides with the set of primes. One example is a polynomial.

- {\ displaystyle {\ begin {aligned} {\ bigl (} k + 2 {\ bigr)} {\ bigl \ {} 1 & - {\ bigl [} wz + h + jq {\ bigr]} ^ {2} - {\ bigl [} (gk + 2g + k + 1) (h + j) + hz {\ bigr]} ^ {2} - {\ bigl [} 2n + p + q + ze {\ bigr]}} { 2} \\ & - {\ bigl [} 16 (k + 1) ^ {3} (k + 2) (n + 1) ^ {2} + 1-f ^ {2} {\ bigr]} ^ { 2} - {\ big [[} e ^ {3} (e + 2) (a + 1) ^ {2} + 1-o ^ {2} {\ bigr]} ^ {2} - {\ bigl [} (a ^ {2} -1) y ^ {2} + 1-x ^ {2} {\ bigr]} ^ {2} \\ & - {\ bigl [} 16r ^ {2} y ^ {4} (a ^ {2} -1) + 1-u ^ {2} {\ bigr]} ^ {2} - {\ bigl [} ((a + u ^ {2} (u ^ {2} -a) ) ^ {2} -1) (n + 4dy) ^ {2} + 1- (x + cu) ^ {2} {\ bigr]} ^ {2} - {\ bigl [} n + l + vy { \ bigr]} ^ {2} \\ & - {\ bigl [} (a ^ {2} -1) l ^ {2} + 1-m ^ {2} {\ bigr]} ^ {2} - { \ bigl [} ai + k + 1-li {\ bigr]} ^ {2} - {\ bigl [} p + l (an-1) + b (2an + 2a-n ^ {2} -2n-2 ) -m {\ bigr]} ^ {2} \\ & - {\ bigl [} q + y (ap-1) + s (2ap + 2a-p ^ {2} -2p-2) -x {\ bigr]} ^ {2} - {\ bigl [} z + pl (ap) + t (2ap-p ^ {2} -1) -pm {\ bigr]} ^ {2} {\ bigr \}} \ end {aligned}}}

containing 26 variables and having degree 25. The smallest degree for known polynomials of this type is 5 with 42 variables; the smallest number of variables is 10 with a degree of about 1.6 · 10 45 [71] [72] . This result is a special case of the diophantability of any enumerable set proved by Yuri Matiyasevich .

Interestingly, the above polynomial, which generates prime numbers, is itself decomposed into factors. Note that the second factor of this polynomial (in curly brackets) has the form: one minus the sum of squares. Thus, the polynomial can take positive values (with positive ) only if each of these squares (that is, each polynomial in square brackets) is equal to zero. In this case, the expression in braces will be equal to 1 [73] .

Open questions

There are still a lot of open questions about primes, the most famous of which were listed by Edmund Landau at the Fifth International Mathematical Congress [74] :

- The Goldbach problem (the first Landau problem ): is it true that every even number greater than two can be represented as a sum of two primes?

- Landau’s second problem : is the set of “simple twins” infinite - pairs of prime numbers, the difference between which is 2? [54] (in 2013, mathematician Zhang Itan from the University of New Hampshire [75] [76] proved that there are an infinitely large number of pairs of prime numbers, the distance between which does not exceed 70 million. Later, James Maynard improved the result to 600. In In 2014, the under the leadership of Terence Tao somewhat improved the latter method, receiving an estimate of 246.)

- Legendre hypothesis ( Landau's third problem ): is it true that for every natural number n between n 2 and ( n + 1) 2 there will always be a prime number? [77]

- The fourth Landau problem : is the set of primes of the form n 2 + 1 infinite, where n is a positive integer? [54]

The open problem is also the existence of an infinite number of primes in many integer sequences, including Mersenne numbers [54] , Fibonacci numbers , Fermat numbers , etc.

Variations and generalizations

Irreducible and simple elements

At the beginning of the article, the definition of a prime number was given: a natural number is called simple if it has exactly two divisors - the unit and the number itself. A similar concept can be introduced in other algebraic structures; most often, commutative rings without zero divisors ( domains of integrity ) are considered [78] [79] . Such rings, however, can have divisors of one , forming a multiplicative group . For example, in the ring of integers there are two divisors of the unit: and Therefore, all integers, except for the divisors of the unit, have not two, but at least four divisors; for example, the number 7 divisors are This means that the generalization of the concept of a prime number should be based on its other properties.

An analogue of a prime number for the integrity domain is an irreducible element . which is defined as follows [80] .

Nonzero element the domain of integrity is called irreducible (sometimes indecomposable ) if it is not a divisor of unity and because of equality follows that or is a unit divider. |

For integers, this definition means that irreducible elements are simple positive integers, as well as opposite ones.

From the definition it follows that the set of divisors of an irreducible element consists of two parts: all the divisors of the unit and the product on all divisors of one (these works are called associated with with elements). That is, the number of divisors of the irreducible if it is, of course, twice the number of divisors of a unit in a ring.

The analogue of the main theorem of arithmetic is important, which is summarized as follows [81] :

A ring is called factorial if in it every non-zero element that is not a unit divider can be represented as a product of irreducible elements, and this representation is unique up to a permutation of the factors and their association (multiplication by unit divisors). |

Not every domain of integrity is factorial, see a counterexample . Euclidean ring is always factorial [82] .

There is another, narrower generalization of the concept of a prime number, called a simple element [80] .

Nonzero element the area of integrity is called simple if it is not a unit divider and the product can be divided into only in the case when at least one of the elements or divided by . |

The element is always irreducible. In fact, if the element simple and then by definition of a simple element one of the factors, let it be divided by i.e Then or reducing by (in the field of integrity, the reduction of a nonzero multiplier is always possible): i.e is a unit divider. ■

The converse is, generally speaking, incorrect, an irreducible element may not be simple if the ring is not factorial. Example [83] : Consider a ring of numbers Where - whole numbers. The number 3 in it is irreducible, since it has only 4 divisors: . However, it is not a simple element, which is what convinces equality:

The number 3 divides the right side of the equality, but does not divide any of the factors. It can be concluded from this fact that the ring considered is not factorial; and in fact equality shows that the decomposition into irreducible factors in this ring is not unique.

Examples

The ring of integers is factorial. In it, as mentioned above, two unit divisors.

Gaussian integers

The ring of Gaussian numbers consists of complex numbers of the form Where - whole numbers. There are four dividers: This ring is factorial, irreducible elements are part of ordinary primes and “simple Gaussian” (for example, ). See the criterion of simplicity of a Gaussian number .

An example of the expansion for the number 2, which in the ring of Gaussian numbers is not simple: - non-uniqueness of decomposition here is apparent, since associated with , according to equality:

Eisenstein integers

Eisenstein Integer Ring consists of complex numbers of the following form [84] :

- Where - whole numbers, ( cube root of one ),

There are six unit divisors in this ring: (± 1, ± ω, ± ω 2 ), it is Euclidean and therefore factorial. Irreducible elements (they are simple elements) of a ring are called Eisenstein prime numbers.

Simplicity criterion : Eisenstein integer is a simple Eisenstein number if and only if one of the following mutually exclusive conditions holds:

- associated with a natural prime number

- (norm ) is a natural simple species or .

It follows that the norm of any Eisenstein integer is either a prime natural number or a square of a prime natural number [84] .

Numbers associated or complex-conjugate with Eisenstein primes are also Eisenstein primes.

Ring of polynomials

Of great importance in algebra is a ring of polynomials formed by polynomials with coefficients from some ring Divisors of units here are non-zero constants (like polynomials of zero degree). The ring of polynomials is Euclidean and therefore factorial. If in quality If we take the field of real numbers , then all polynomials of the 1st degree will be irreducible and those of the 2nd degree will have a discriminant that is negative.

See also

- Illegal prime number

- Supersimple number

- Semi-simple number

- Primorial

- Prime numbers that differ by six

- Random prime

- Composite number

- List of prime numbers

- Unique simple

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 Simple Number // Mathematical Encyclopedia (in 5 volumes) . - M .: Soviet Encyclopedia , 1977. - T. 4.

- ↑ 1 2 " " Arguments for and against the primality of 1 ". (English)

- ↑ The sequence A000040 in OEIS , see also the list of prime numbers

- ↑ Gardner, Martin . From Penrose mosaics to robust ciphers = Penrose Tiles to Trapdoor Ciphers / lane. from English Yu. A. Danilov. - M .: [[World (Publishing House) |]], 1993. - 416 p. - 10 000 copies - ISBN 5-03-001991-X .

- Ф (fr.) Préhistoire de la géométrie: le problème des sources (PDF) (not available link) . Site de l'irem de la Réunion. Voir aussi "Les fables d'Ishango, ou l'irrésistible tentation de la mathématique-fiction" , analyze par O. Keller sur Bibnum

- ↑ edition = Mathpages Egyptian Unit Fractions .

- ↑ 1 2 Rybnikov K. Russian publications of the Beginnings of Euclid. (Rus.) // Successes of Mathematical Sciences . - Russian Academy of Sciences , 1941. - № 9 . - p . 318-321 .

- ↑ John J. O'Connor, Edmund F. Robertson. Prime numbers . MacTutor .

- ↑ List of Known Mersenne Prime Numbers . Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search .

- 2 1 2 3 Apostol, Tom M. - New York: Springer-Verlag, 1976. - xii, 338 pages p. - ISBN 0387901639 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 Du Sautoy, Marcus. L'enigma dei numeri primi . - Milano: Rizzoli, 2005. - 606 p. with. - ISBN 8817008435 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 Menezes, AJ (Alfred J.), 1965-. Handbook of applied cryptography . - Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1997. - xxviii, 780 pages p. - ISBN 9780849385230 .

- ↑ 1 2 Ishmukhametov Sh. T. Methods of factorization of natural numbers: a training manual // Kazan: Kazan University. - 2011. - p . 190 .

- ↑ Dudley, Underwood (1978), Elementary number theory (2nd ed.), WH Freeman and Co., ISBN 978-0-7167-0076-0 , Section 2, Theorem 2

- ↑ Dudley, Underwood (1978), Elementary number theory (2nd ed.), WH Freeman and Co., ISBN 978-0-7167-0076-0 , Section 2, Lemma 5 (Eng.)

- ↑ See, for example, David E. Joyce's Commentary on Beginnings (Euclid) , Book VII, definitions 1 and 2 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 Why is it not number one? (from the Prime Pages' list of frequently asked questions) by Chris K. Caldwell. (eng.)

- ↑ See for instance: L. Euler. Commentarii academiae scientiarum Petropolitanae 9 (1737), 160–188. Variae observationes circa series infinitas, Theorema 19, p.187. (eng.)

- ↑ Derbyshire, John (2003), "The Prime Number Theorem", The Prime Obsession: Bernhard Riemann and the Greatest Unsolved Problem in Mathematics , Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press, p. 33, ISBN 978-0-309-08549-6 , OCLC 249210614 (eng.)

- ↑ David Gries, Jayadev Misra. A Linear Sieve Algorithm for Finding Prime Numbers. - 1978.

- ↑ Knuth, Donald Ervin, 1938-. The art of computer programming . - Reading, Mass .: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co, © 1973- © 1981. - 4 volumes with. - ISBN 0201896842 .

- ↑ 1 2 Vasilenko, ON (Oleg Nikolaevich). Teoretiko-chislovye algoritmy v kriptografii . - Moskva: MT︠S︡NMO. Moskovskiĭ t︠s︡entr nepreryvnogo matematicheskogo obrazovanii︠a︡, 2006. - 333 pages p. - ISBN 5940571034 .

- ↑ B. Schneier. Applied cryptography. - p. 296-300.

- ↑ Kormen T., Leiser C. Algorithms. Construction and analysis. - M .: MTSNMO, 2002. - p. 765-772.

- ↑ Crandall R., Pomerance C. Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective. - Springer, 2005.

- ↑ Introduction to algorithms . - 2nd ed. - Cambridge, Mass .: MIT Press, 2001. - xxi, 1180 pages p. - ISBN 0262032937 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Yu. V. Nesterenko. Introduction to cryptography. - Peter, 2001. - 288 p.

- ↑ Chris Caldwell. The Largest Known Prime Year: A Brief History (eng.) . The Prime Pages .

- ↑ Jitsuro Nagura. Proceedings of the Japan Academy. - 1952. - V. 28 , no. 4 - p . 177-181 . - ISSN 0021-4280 . - DOI : 10.3792 / pja / 1195570997 .

- ↑ Letter in Latin from Goldbach to Euler, July 1730.

- ↑ Records of prime numbers by year

- ↑ Starr, Michelle . The Beat is Our Discovery And Hurting Our Brains (en-gb), ScienceAlert . The appeal date is January 6, 2018.

- ↑ EFF Cooperative Computing Awards (English)

- ↑ Julia Rudy. A professor from the United States identified the largest prime number . Vesti.ru (February 7, 2013). The appeal date is February 25, 2018.

- ↑ 1 2 Sequence A001348 in OEIS

- ↑ Sequence A000668 in OEIS : Mersenne Prime Numbers

- ↑ Sequence A000215 in OEIS

- ↑ Keller, Wilfrid (February 15, 2015), Prime Factors of Fermat Numbers , < http://www.prothsearch.net/fermat.html#Summary > . Verified March 1, 2016. Archived copy of February 10, 2016 on Wayback Machine

- ↑ Violant-i-Holtz, Albert. Riddle Farm. Three centuries of math challenge. - M .: De Agostini, 2014. - p. 78. - 151 p. - (World of Mathematics: in 45 volumes, volume 9). - ISBN 978-5-9774-0625-3 .

- ↑ Sequence A003261 in OEIS

- ↑ Sequence A050918 in OEIS : Wooda prime numbers

- ↑ Sequence A002064 in OEIS

- ↑ Sequence A050920 in OEIS : Cullen Prime Numbers

- ↑ Sequence A080075 in OEIS

- ↑ John Brillhart ; Derrick Henry Lehmer ; John Selfridge . New Primality Criteria and Factorizations of 2 ^ m ± 1 (Eng.) // Mathematics of Computation : journal. - 1975. - April ( vol. 29 ). - P. 620-647 . - DOI : 10.1090 / S0025-5718-1975-0384673-1 .

- ↑ Sequence A080076 in OEIS : Prot Prime Numbers

- ↑ Caldwell, Chris K. & Cheng, Yuanyou (2005), " Determining Mills' Contents and a Note on Honaker's Problem ", Journal of Integer Sequences T. 8 (5.4.1) , < http: //www.cs.uwaterloo .ca / journals / JIS / VOL8 / Caldwell / caldwell78.html >

- ↑ 1 2 3 Stepanov S. A. Comparisons . - M .: "Knowledge", 1975. - 64 p.

- ↑ Winberg, 2008 , p. 43.

- ↑ 1 2 Kurosh A. G. Theory of groups. 3rd ed., M .: Science, 1967.

- ↑ A. I. Kostrikin. Introduction to Algebra, Part III. M .: Fizmatlit, 2001.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Vinogradov IM Fundamentals of the theory of numbers . - 5 ed .. - M.-L .: Gostekhizdat, 1952.

- Cal Chris Caldwell, Bertrand's Postulate at Glossary.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Encyclopedic Dictionary of Young Mathematics, 1985 .

- Proof . An odd number p , not a multiple of 3, is 1 or 2 modulo 3 and is 1, 3, 5 or 7 modulo 8. When squared, this gives 1 modulo 3 and 1 modulo 8. Subtracting 1, we get 0 by modulo 3 and 0 modulo 8. Therefore, a multiple of 3 and a multiple of 8; therefore, it is a multiple of 24

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. Green-Tao Theorem (Eng.) On the Wolfram MathWorld website.

- ↑ These 2 properties directly follow from the decomposition formulas of the sum and the difference of degrees

- Ю Encyclopedic Dictionary of Young Mathematics, 1985 , p. 332.

- ↑ 1 2 Graham, Ronald L. (1935-). Konkretnaâ matematika: osnovanie informatiki . - Moskva: Izdatelʹstvo "Mir", 1998. - 703, [1] s. with. - ISBN 5030017933 .

- ↑ Sandifer, Charles Edward, 1951-. The early mathematics of Leonhard Euler . - Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, 2007. - xix, 391 pages p. - ISBN 0883855593 .

- ↑ Bach, Eric. Algorithmic number theory . - Cambridge, Mass .: MIT Press, © 1996-. - volumes <1> p. - ISBN 0262024055 .

- ↑ WR Alford, Andrew Granville, Carl Pomerance. There are Infinitely Many Carmichael Numbers // Annals of Mathematics. - 1994. - V. 139 , no. 3 - p . 703-722 . - DOI : 10.2307 / 2118576 .

- ↑ Charles C. Sims. Enumerating p-Groups (Eng.) // Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society. - 1965-01-01. - Vol. s3-15 , iss. 1 . - P. 151-166 . - ISSN 1460-244X . - DOI : 10.1112 / plms / s3-15.1.151 .

- ↑ Jacobson, Nathan, 1910-1999. Basic algebra . - 2nd ed., Dover ed. - Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2009. - 2 volumes with. - ISBN 9780486471877 .

- ↑ Sagalovich Yu.L. Introduction to algebraic codes . - 2011. - 302 p.

- ↑ Ferguson, Niels. Practical cryptography . - New York: Wiley, 2003. - xx, 410 pages p. - ISBN 0471223573 .

- ↑ W. Diffie, M. Hellman. New directions in cryptography // IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. - November 1976. - V. 22 , no. 6 - p . 644-654 . - ISSN 0018-9448 . - DOI : 10.1109 / tit.1976.1055638 .

- ↑ Bakhtiari, Maarof, 2012 , p. 175.

- ↑ Boneh D. Twenty Years of attacks on the RSA Cryptosystem // Notices Amer. Math Soc. / F. Morgan - AMS , 1999. - Vol. 46, Iss. 2. - P. 203–213. - ISSN 0002-9920

- ↑ 1 2 RSA Laboratories, The RSA Factoring Challenge Archived {{{2}}}. . Published May 18, 2007.

- ↑ Jones JP, Sato D., Wada H., Wiens D. Diophantine representation of the set of prime numbers (English) // Amer. Math Mon. : journal. - 1976. - Vol. 83 , no. 6 P. 449-464 . Archived March 31, 2010.

- ↑ Yuri Matiyasevich, Diophantine Equations in the XX Century (inaccessible link)

- ↑ Matijasevic's polynomial . The Prime Glossary.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. Landau's Problems (Eng.) On Wolfram MathWorld .

- ↑ Unknown mathematician made a breakthrough in the theory of twin prime numbers

- ↑ Bounded Gaps Between Primes

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. Legendre Gitoteza (English) on Wolfram MathWorld .

- ↑ A generalization to arbitrary semigroups, see Kurosh’s book.

- ↑ Van der Waerden, 2004 , p. 75

- ↑ 1 2 Kurosh, 1973 , p. 82–83.

- ↑ Leng, 1967 , p. 89

- ↑ Van der Waerden, 2004 , p. 77-78.

- ↑ William W. Adams, Larry Joel Goldstein (1976), Introduction to Number Theory, p. 250, Prentice-Hall, Inc., ISBN 0-13-491282-9

- ↑ 1 2 Eisenstein Integer - from MathWorld

Literature

- Van der warden . Algebra. Definitions, theorems, formulas. - SPb. : Lan, 2004. - 624 p. - ISBN 5-8114-0552-9 .

- Vasilenko O.N. Number-theoretic algorithms in cryptography . - M .: MTSNMO , 2003. - 328 p. - ISBN 5-94057-103-4 .

- Vinberg, E. B., Fermat's Small Theorem and Its Generalizations, Mat. prow. - M .: Publishing house ICNMO , 2008. - T. 12. - P. 43–53.

- Galperin G. Just about prime numbers // Kvant . - № 4 . - pp . 9-14,38 .

- Henry S. Warren, Jr. Chapter 16. Formulas for prime numbers // Algorithmic tricks for programmers = Hacker's Delight. - M .: “Williams”, 2007. - 288 p. - ISBN 0-201-91465-4 .

- Karpushina N. Palindromes and "turncovers" among prime numbers (rus.) // Science and Life . - 2010. - № 5 .

- Kordemsky B. А. Mathematical sharpness . - M .: GIFML, 1958. - 576 p.

- Kormen, T., Leiser, Ch. Chapter 33.8. Checking numbers for simplicity // Algorithms. Construction and analysis . - M .: MTSNMO, 2002. - p. 765-772. - ISBN 5-900916-37-5 .

- Crandall, R. , Pomerans, K. Prime numbers. Cryptographic and computational aspects = Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective. - M .: URSS , Librokom, 2011. - 664 p. - ISBN 978-5-397-02060-2 .

- Kurosh A.G. Lectures on general algebra. - 2nd ed .. - Science, 1973.

- Leng S. Algebra. - M .: Mir, 1967.

- Matiyasevich Yu . Formulas for prime numbers // Kvant . - 1975. - № 5 . - p . 5-13 .

- Nesterenko Yu. V. Algorithmic problems of number theory // Introduction to cryptography / Edited by V. V. Yashchenko. - Peter, 2001. - 288 p. - ISBN 5-318-00443-1 .

- A prime number // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Young Mathematics / Comp. A.P. Savin. - M .: Pedagogy , 1985. - 352 p.

- Enrique Gracian Prime numbers. Long road to infinity. - De Agostini, 2014. - Vol. 3. - 148 p. - (The world of mathematics). - ISBN 978-5-9774-0682-6 . - ISBN 978-5-9774-0637-6 .

- Bakhtiari M. , Maarof M. A. Serious Security Weakness in RSA Cryptosystem // IJCSI - 2012. - Vol. 9, Iss. 1, No 3. - P. 175-178. - ISSN 1694-0814 ; 1694-0784

- Crandall R., Pomerance C. Chapter 3. Recognizing Primes and Composites. Chapter 4. “Primality Proving” // Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective . - Springer, 2005. - pp. 117-224. - ISBN 0-387-25282-7 .

Links

- Knop K. In pursuit of simplicity .

- The Prime Pages (Eng.) - the database of the largest known prime numbers (Eng.) .

- Geometry of simple and perfect numbers (isp.) .

- Visualization script