The Laplata War (August 18, 1851 - February 3, 1852) is an armed conflict between the Argentine Confederation on the one hand, and the Brazilian Empire , Uruguay, and the Argentine provinces of Entre Rios and Corrientes on the other. The war was part of a long-standing confrontation between Argentina and Brazil for influence over Uruguay and Paraguay , and for dominance over the La Plata region (territories located next to the La Plata estuary ). The war went on in Uruguay, in northeastern Argentina and around the La Plata basin.

| Laplat war | |||

|---|---|---|---|

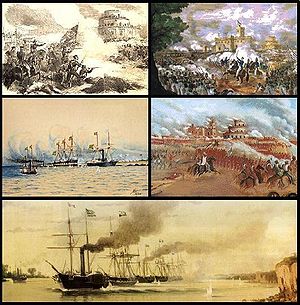

Clockwise, starting from the upper left corner - the 1st Brazilian division under Caseros; the Uruguayan infantry assists the Entre Rios cavalry at the Battle of Caseros; Urkisa’s cavalry charges; passage through Tonelero; start of passage through Tonelero. | |||

| date | August 18, 1851 - February 3, 1852 | ||

| A place | Uruguay | ||

| Cause | Helping Brazil Resist Uruguay | ||

| Total | The victory of the Brazilian empire and its allies | ||

| Opponents | |||

| |||

| Commanders | |||

| |||

| Forces of the parties | |||

| |||

| Losses | |||

| |||

In 1850, political instability reigned in the La Plata region. Despite the fact that the governor of Buenos Aires, Juan Manuel de Rosas , using his position, achieved undivided power over the Argentine provinces, during his reign there were regional uprisings. At the same time, there was a long-term civil war in Uruguay. In this conflict, Rosas supported the Uruguayan Blancos party ; he wanted to include in Argentina all the territories that once belonged to the Spanish Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata . To achieve this, it was necessary to gain control of Uruguay, Paraguay and Bolivia. Rosas's intentions also threatened Brazilian interests and Brazilian independence, as the former Viceroyalty included territories that later became part of the Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul .

Brazil actively tried to eliminate the threat from Roses. In 1851, she entered into an alliance with the breakaway Argentine provinces of Corrientes and Entre Rios (headed by Justo José de Urquiz ), and the Uruguayan party opposed to Roses. Brazil then secured the southwestern borders by creating a defensive alliance with Paraguay and Bolivia. Roses, seeing that a coalition had formed against him, declared war on Brazil. After that, allied forces invaded Uruguay, defeating the party of Manuel Oribe , which was supported by Rosas. Then the allied army split up: the main part on land advanced to the main defensive lines of Roses, and the other launched a naval attack on Buenos Aires .

The Laplatian War ended in 1852, when the Allied forces won the battle of Caseros . As a result, Brazil gained dominance over most of South America . As a result of the war in the Brazilian empire, a period of economic and political stability began. With the elimination of Rosas, a process began in Argentina, which subsequently led to greater unification of the country. However, the end of the war did not completely solve all the problems in the La Plata region. In subsequent years, instability reappeared: in Uruguay, internal contradictions between political forces intensified, a long civil war resumed in Argentina, and developing Paraguay began to defend its interests. In the next two decades, due to territorial claims and disputes over influence, two more major wars broke out between the states of this region.

Background

Argentina Civil Wars

After a short period of anarchy, which began in 1828 after the end of the Argentine-Brazilian war , don Juan Manuel de Rosas became governor of Buenos Aires. De jure Rosas had exactly the same powers as the governors of other Argentine provinces, but de facto he ruled the entire Argentine Confederation. Despite the fact that he was a federalist - a member of the party that advocated greater autonomy of the provinces - in fact, Rosas’s power extended to other provinces: he was the de facto head of Argentina [6] . During his twenty-year reign in the country, armed clashes resumed between the Unitarians (the party that was in opposition to him) and the federalists. [6] [7] [8]

Roses wanted to restore the former Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata. He sought to create a strong state of the republican type, in which Argentina would occupy a central place. [9] [10] The former vice kingdom at the beginning of the 19th century, after gaining independence , split into several independent states. To restore it, the Argentine government had to annex three neighboring states - Bolivia , Uruguay and Paraguay - as well as annex part of the Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul. [11] For starters, Roses needed to gather regional allies who shared his idea. In some cases, he had to intervene in the internal affairs of neighboring countries, support groups advocating for unification with Argentina, and even finance wars and uprisings. [eleven]

Since 1811, Paraguay considered itself an independent state, but other countries did not recognize its sovereignty. Argentina considered it a rebellious province. Paraguayan dictator Jose Gaspar Rodriguez de France considered that in order to preserve Paraguay’s rule and independence from Argentina, it is necessary to isolate the country from the outside world. It is for this reason that Paraguay did not have diplomatic relations with other states until 1840. [12] After the death of Francis, this political course began to change, and his successor, Don Carlos Antonio Lopez , in July 1841 signed two treaties with the breakaway province of Corrientes from Argentina: the treaty of “ friendship, trade and navigation ” and the “ border treaty ” . [13] At the same time, Rosas pressured Paraguay: he refused to recognize his independence and blocked international traffic on the Parana River to and from Paraguay. [13]

Uruguay Civil War

The internal problems of Uruguay, including the protracted civil war, were significant factors that led to the Laplata war. After the Argentine-Brazilian war , which went on in the 20s of the XIX century, the former Brazilian province of Sisplatina became the Eastern Republic of Uruguay [7] . Soon the country was mired in a long civil war between the two parties - Blancos, whose leader was Juan Antonio Lavalleja , and Colorados, whose head was Don Fructuoso Rivera [7] .

Lavalleja learned that Rosas from neighboring Buenos Aires is interested in providing him with financial and military assistance [7] . In 1832, Lavalleja began to receive assistance [14] from Bento Gonçalves da Silva , a soldier and farmer from the Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul. In 1835, Gonçalves, with the support of Roses, organized an uprising against the Brazilian government so that Argentina could annex the province of Rio Grande do Sul [15] [16] . Lavalleja and Gonçalves launched a military campaign against Uruguay; she was characterized by significant robberies and cruelty [17] . Gonçalves betrayed Roses and Lavallej, on the side of Fructuoso Rivera [9] [18] , after which both invaded Uruguay and captured most of the territory in the vicinity of the country's capital, Montevideo . Having been defeated, the then president of Uruguay, Manuel Oribe (who, like Lavalleja, was a member of the Blancos party [17] [19] ) resigned and fled to Argentina [20] .

Roses was determined to restore Argentina's suzerainty over Uruguay, and to avenge Gonçalves. This has led to a number of interventions. In 1839, troops led by Lavalleja, Oribe and Justo José de Urquiza (Governor of the province of Entre Rios ) were defeated by Rivera. After that, Lavalleja ceased to participate in the civil war [21] . In 1845, Rosas sent another army led by Oribe [19] and Urkisa [9] , consisting of Argentines and Uruguayans. This time they managed to defeat the forces of Rivera; all survivors were killed. Rivera was one of the few who managed to escape [22] . He fled to Rio de Janeiro [23] [24] . The remaining forces of Colorados controlled only the country's capital, Montevideo, while the forces of Oribe began to besiege it [21] . Violence in Uruguay escalated: during the conflict, people of Oribe killed more than 17 thousand Uruguayans and 15 thousand Argentines [25] .

Oribe captured almost the entire territory of Uruguay, and this allowed him to launch an attack on the south of Brazil. During the offensive, his people stole cattle, looted and killed political enemies [24] . 188 Brazilian farms were attacked: 814 thousand heads of cattle and 16 950 horses were stolen [26] . The local population, independently of each other, in revenge began to carry out raids on Uruguayan territories - they were called " Califórnias " [27] [28] [29] , in honor of the uprising in North America of California against Mexico [30] [31] . As the conflict escalated, amid continued support from Blancos by Manuel de Rosas, anarchy spread in the region. Due to the growing threat to trade, France and Britain - the two greatest powers of the time - were forced to declare war on Argentina [9] . The Anglo-French fleet made a series of attacks on Buenos Aires. The city also . However, the Argentine government managed to organize effective resistance, and this led to the signing of a peace treaty in 1849 [27] [32] .

Actions of the Brazilian Empire

By the mid-19th century, the Brazilian empire was the richest [33] and most powerful state in South America. [34] Democratic institutions and a constitutional monarchy reigned in it. On her account there were no caudillos, dictators and military coups, which was unusual for South America. However, during the minority of Emperor Don Pedro II , in the 30s of the XIX century, uprisings took place in some internal provinces of the country, fueled by the local struggle for power. [35] One such revolution, the Farrapus War, was led by Bento Gonçalves.

The expansionist plans of a strong Republican Argentina posed a threat to the existence of the Brazilian Empire. They also threatened Brazilian hegemony on the southern borders. If Argentina annexed Paraguay and Uruguay to the revived Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata (and gained control of the river network of the La Plata estuary [36] [37] ), Brazil would be in danger of losing touch with the provinces of Mato Grosso and Rio de Janeiro: ground communications, unlike river communications, would take whole months, not several days. [36] [37] It was also undesirable for Brazil to have a common border with Argentina, due to the increased risk of Rosas attack. [36] [38]

The members of the Brazilian cabinet could not come to a common agreement on how to get rid of the threat from Rosas. Some ministers favored a peaceful settlement at all costs. They feared that Brazil was not ready for war and that defeat would lead to chaos, as happened in the 1920s, when, after the loss of the province of Sisplatin, the emperor’s father, don Pedro I, abdicated. Other ministers believed that only military intervention could eliminate the threat. However, in 1849, Paulinho José Soares de Soza, a member of the party in favor of the war, who later became Viscount of Uruguay, was elected the new Minister of Foreign Affairs. [39] Soza made it clear that he intends to solve the problem without foreign support: “The imperial government does not want and does not consider it appropriate to enter into an alliance with France or any other European country, when it comes to problems in the La Plata region. The government believes that they should be decided by countries with which we have close ties ... We do not recognize European influence over America . " The emperor of Brazil intended to expand the sphere of influence of his country to all of South America. [40]

The Cabinet of Ministers chose a risky alternative measure to solve a difficult issue: instead of starting an expensive buildup of armed forces with the help of conscription, the Cabinet decided to rely on a standing army. A contingent of soldiers was sent to defend the southern region. Brazil had an advantage in the form of a modern and strong navy, as well as an experienced professional army, hardened in internal and external military conflicts. [41] Until this moment, no other South American state possessed a real fleet and a standing army. The forces of Rosas and Oribe for the most part consisted of temporary troops, which were provided by the caudillos. [42] Even after ten years, the army of Argentina numbered only 6 thousand people. [43] Brazil also began to use Rosas tactics, financing his opponents in order to weaken him both from the inside and from the outside. [10] [44] [45]

The beginning of the war

Union vs Roses

The Brazilian government began to form a regional alliance against Roses, sending a delegation to the region controlled by Honorio Ermet Carneiro Lean (which would later become the Marquis of Parana). His assistant was Jose Maria da Silva Paranos, the future Viscount Rio Branco. Brazil signed an agreement with Bolivia, according to which Bolivia agreed to strengthen the protection of its borders in order to deter any attack by Rosas. At the same time, she refused to allocate troops for the war with Argentina. [46] Convincing isolated Paraguay proved to be more difficult. The first thing in 1844, Brazil formally recognized the independence of Paraguay, becoming the first such country. [9] This soon led to the establishment of excellent diplomatic relations. Brazil's ambassador to Paraguay, Pimenta Bueno, became personal adviser to Carlos Lopez. [13] December 25, 1850 [27] [47] Brazil and Paraguay signed an agreement to establish a defensive alliance [48] , according to which Lopez agreed to equip the army of the Brazilian Empire with horses. [38] But he also refused to allocate troops for the battle against Roses, because he believed that the ruler of the Argentine province of Entre Rios, Justo José de Urquiz (who invaded Uruguay in 1839 and 1845), secretly wanted to annex Paraguay. [2]

Brazil's participation in the Uruguayan civil war began to increase. Luis Alvish di Lima and Silva - Count of Caxias - became governor of Rio Grande do Sul and took command of the four divisions of the Brazilian army, which had headquarters in this province. [31] Beginning in 1849, the imperial government began to directly assist the Uruguayan government of Colorado, who was besieged in Montevideo, and on September 6, 1950, the representative of Uruguay, Andres Lamas, signed an agreement with Irineu Evangelista di Soza , according to which finances were transferred to the Montevideo government through the Bank of di Soza. [38] [49] [50] On March 16, 1851, the Brazilian Empire openly declared its support for the Uruguayan party Colorados, which opposed Oribe - for more than two years it has been doing this secretly. It did not like the Argentine government, which began mobilization for the war. [48] [51]

Brazil, with some success, also tried to gain support against Roses and in Argentina itself. On May 1, 1851, the province of Entre Rios, still governed by Urkisa, declared to Rosas: " by the will of the people, the province regains all the power and independence that was transferred to the governor of Buenos Aires ." It was followed by the province of Corrientes, which was ruled by Benjamin Virasoro; the statement was the same. [52] Brazil contributed and supported financially both rebellions. One of the reasons for the transition of Urkisa to the side of the coalition was the long-standing rivalry between him and Rosas. In 1845, Rosas tried several times to remove him from his post, as he suspected that the caudillos had plans to overthrow him. [27] Uprising became a pretext for military intervention, and Brazil sent its fleet to the La Plata region, deploying it near Montevideo. British Rear Admiral John Pasco Grenfel, a veteran of the Brazilian War of Independence and the Argentine-Brazilian War, was appointed fleet commander. [46] The fleet arrived in Montevideo on May 4, 1851. It consisted of one frigate , seven corvettes , three brigs and six steamers . [51] [53] In 1851, the Brazilian armada consisted of 59 ships of various types: 36 battle sailing ships, 10 battle steamers, 7 unarmed sailing ships and 6 sailing transport ships. [54]

On May 29, 1851, Uruguay, Brazil, and two Argentine provinces - Entre Rios and Corrientes - formed an offensive alliance against Roses. The agreement declared that the purpose of the alliance was to protect Uruguay’s independence, restore order on its territory and expel the forces of Oribe. [28] Urkisa was to command the Argentine forces, and Eugenio Garzon - Uruguayan Colorado; both were to receive financial and military assistance from the Brazilian empire. [51] August 2, 1851 was followed by the landing of the first Brazilian detachment of troops in Uruguay to protect Fort Kerro. [55] The detachment consisted of approximately 300 soldiers of the 6th Infantry Battalion. On August 18, 1851, Roses declared war on Brazil. [56]

Allied invasion of Uruguay

September 4, 1851, the Brazilian army, consisting of 16.2 thousand professional soldiers, led by Luis Silva crossed the border between Rio Grande do Sul and Brazil. His forces consisted of four divisions: there were 6.5 thousand infantrymen, 8.9 thousand cavalrymen, 800 artillerymen and 26 cannons [57] (a little less than half the Brazilian army, numbering 37 thousand soldiers [58] ). Another 4 thousand of his soldiers remained in Brazil to protect the borders. [57]

The Brazilian army entered Uruguay in three groups. The main forces - 1st and 2nd divisions - came out of the city of Santana do Livramento . Their number was approximately 12 thousand people; Silva personally commanded them. The second group, under the command of Colonel David Canabaro, advanced from the city of Quarai . It consisted of the 4th division, and its task was to protect the right flank of Luis Silva. The third group - the 3rd division of Brigadier General José Fernandez - left the city of агaguaran and defended Silva's left flank. Kanabaro's 4th Division, shortly after arriving in the Uruguayan city of Frutuoso, joined forces with Silva. Before arriving in Montevideo, their forces joined forces with Fernandez. [59]

Capitulation of Oribe

Meanwhile, the troops of Urkisa and Garzon surrounded the army of Oribe near Montevideo. Their forces (15 thousand soldiers) were almost twice the strength of Oribe (8.5 thousand soldiers). Soon, Oribe learned that the Brazilians were also approaching to help his opponents, which would make his position already completely hopeless. Realizing that there was no chance of winning, Oribe ordered his troops to surrender without a fight on October 19 [52] [46] . Oribe himself, having received guarantees of personal integrity, retired to his farm in Paso del Molino, where he spent the rest of his life. The Brazilian fleet, which established control over the entire La Plata and its tributaries, did not allow the defeated army of Oribe to leave for Argentina and she was forced to surrender. [51] [60] Urkis offered Grenfel to kill all prisoners of war, but Grenfel categorically refused to kill any of them. [61] Instead, Argentines from the army of Oribe were enlisted in the army of Urkisa, and Uruguayans were included in the troops of Garzon. [62]

The Brazilian army easily captured the remaining Uruguayan territory, which was under the control of Blancos, repelling several flank attacks by the surviving forces of Oribe. [60] On November 21, in Montevideo, representatives of Brazil, Uruguay, Entre Rios and Corrientes formed a new alliance [63] , whose mission was to “liberate the people of Argentina from the oppression of the tyrant Rosas”. [64]

Allied invasion of Argentina

Offensive of the Allied Army

Soon after the surrender of Oribe, the allied forces divided into two groups: the first was to go up the river and attack Buenos Aires from the city of Santa Fe, and the second was to land at the port of Buenos Aires itself. The first group consisted of Uruguayans, Argentines and the 1st division of the Brazilian army; it was commanded by Brigadier General Manuel Marquez di Soza (who later became Count of Porto Alegre). Initially, it was located in the southern Uruguayan city of Colonia del Sacramento, opposite the estuary of the Plata River. [65]

On December 17, 1851, a squadron of Brazilian ships, consisting of four steamboats, three corvettes and one brig, under the command of John Pasco Grenfel, with a battle passed along the Parana River ; the battle was called " Passage through Tonelero ." The Argentines built a powerful defensive line at Tonelero: it was protected by 16 artillery mounts and 2 thousand shooters; commanded by the defense of General Lucio Norberto Mansilla. [64] Argentine troops fired at Brazilian ships, but could not prevent them from going upstream. [66] The next day, the Brazilian ships returned and broke through the defensive lines of Tonelero; they drove the remaining troops of Marquez de Soza to the city of Gualeguacu. The second arrival of the ships forced Mansilla and his soldiers to retreat, abandoning artillery, as he feared that the Allies intended to land and attack his position from the rear. [67]

The Allies continued to move to the gathering point in the city of Gualeguacu. Urkis and his cavalry sailed from Montevideo, while infantry and artillery were transported by Brazilian ships along the Uruguay River. Joining in the appointed place, they moved west, and in the middle of December 1851 [68] reached the city of Diamante, which is located on the eastern bank of the Parana River. Brazilian ships took Eugenio Garzon and his Uruguayan troops from Montevideo and transported them to Potrero Perez. From there, they walked to Diamante. On December 30, 1851, all Allied forces reunited. [68] From Diamante they were transported to the other side of the Parana River - to the city of Santa Fe . [68] The troops of the Argentine Confederation stationed in this region fled without any resistance. [68] The allied army, which Urkis officially called the "Great Army of South America," moved to Buenos Aires. [68]

Meanwhile, the second group under the command of Silva, consisting mainly of Brazilian soldiers (12 thousand), remained in the city of Colonia del Sacramento. Silva, on the boat " House Afonso " (which was named after the late Prince Afonso) arrived at the port of Buenos Aires to choose the best place for landing troops. He feared that he would have to defeat the Argentine flotilla based in the port, but the flotilla did nothing, and he returned safely to Sacramento to continue preparations for the attack. [69] However, the naval attack was canceled before it began, as news came of the victory of the Allied forces in the land battle of Caseros. [67] [70]

Defeat of Rosas

The allied army attacked the Argentine capital Buenos Aires from land, while the Brazilian army under the command of di Silva was supposed to attack from the sea. On January 29, at the battle of Alvarez Field, the Allied lead detachment defeated a four-thousand-strong Argentine army, which was sent by General Angel Pacheco to slow the Allied offensive. [71] Pacheco escaped. Two days later, two allied divisions at the Battle of Marquez Bridge defeated the troops that General Pacheco personally commanded. [71] [72] On February 1, 1852, the Allied forces camped nine kilometers from Buenos Aires. The next day, after a short skirmish between the head units of the two armies, the Rosists fled. [73] [74]

On February 3, the Allied forces had a decisive battle at Caseros with the main forces of Roses, commanded by the dictator himself as commander in chief. Nominally, the forces of the parties were approximately equal. Allied forces totaled 20 thousand Argentines, 2 thousand Uruguayans, 4 thousand [3] elite Brazilian soldiers [4] ; in total, 26 thousand soldiers and 45 cannons (16 thousand cavalrymen, 9 thousand infantrymen, thousand artillerymen) came out. [5] The forces of Rosas totaled 15 thousand cavalrymen, 10 thousand infantrymen and a thousand artillerymen; in total, 26 thousand soldiers and 60 guns came out. [76] Roses had the opportunity to choose the best positions for his troops: he chose a high position on a hillside near Caseros, located on the other side of Moron Harbor. His rate was located on the estate, which stood at the highest point of the city of Caseros. [five]

The allies commanders were di Sosa, Manuel Luis Osorio, Jose Maria Piran, Jose Miguel Galan (who replaced Garcon after his unexpected death in December 1851), Justo Urquiz and future Argentinean presidents - Bartolome Miter and Domingo Sarmiento . They formed the Military Council, and gave the order to launch an offensive. [3] Almost immediately, the advanced units of both armies entered the fray. [five]

The battle of Caseros ended with a significant victory for the Allies. Despite the fact that they started the battle from the worst positions, the Allied soldiers in the battle, which lasted almost the whole day, were able to defeat the troops of Roses. The Argentine dictator managed to escape a few minutes before the allied forces reached his headquarters. Disguised as a sailor, [70] he sought out Robert Gore, the British ambassador in Buenos Aires, and sought refuge. The ambassador agreed to take de Rosas and his daughter, Manuelita, to the UK; there he spent the last twenty years of his life. [46] [3] The official report stated that 600 people were injured or killed among the Allies, while the Argentine side lost 1.4 thousand people wounded or killed; 7 thousand soldiers were captured. However, given the time and scope of the battle, this data may be underestimated. [77] [78]

In commemoration of the victory, the Allied forces marched through the streets of Buenos Aires. The Brazilian army participated in the parades, which insisted that their triumphal procession take place on February 20, in retaliation for the defeat that she experienced at the battle of Itusingo exactly 25 years ago. It was reported that the population of Buenos Aires looked at the procession of the Brazilians in silence, with a sense of shame and hostility. [3]

Consequences

For Brazil

The triumph at Caseros was a turning military victory for Brazil. The independence of Paraguay and Uruguay was ensured, and Argentina's planned attack on the province of Rio Grande do Sul was disrupted. [79] For three years, the Brazilian empire eliminated all chances of rebuilding a state that would include the territories of the former Viceroyalty of Rio de la Palata - the cherished goal of many in Argentina since independence. [52] The Brazilian army and navy did what the strong flotillas of the great powers of that time — Great Britain and France — could not achieve. [80] This marked a turning point in the history of the region, not only because Brazil gained dominance over the La Plata region [2] [3] , but also because, according to the Brazilian historian Maye Pedroze, Brazil established hegemony over the rest part of South America. [34] The victory over Paraguay, after eighteen years, will only strengthen Brazil's dominance.

The Hispanic peoples of the American countries, from Mexico to Argentina, suffered from coups, uprisings, dictators, political upheavals, economic instabilities, civil wars and divisions. On the contrary, the constitutional monarchy of Brazil only strengthened after the war; internal uprisings also ceased. The problematic province of Rio Grande do Sul, where there were strong separatist sentiments, actively participated in hostilities on the side of the government. As a result, identification with Brazil intensified among its population, separatist sentiments faded and easier and more effective integration with the rest of the country took place. [76] Internal stability allowed Brazil to begin to take its rightful place in the international arena. This coincided with the advent of the United States of America, which had just set its borders. European states saw the Brazilian Empire as a rare exception to all the rest of the continent, mired in civil wars and dictatorships. [81] A period of tremendous economic, scientific, and cultural dawn began in Brazil, which lasted from 1850 until the end of the reign of the monarchy. [82] [83]

For Argentina

Soon after the battle of Caseros, the San Nicholas agreement was signed. It was supposed to act within the framework of the constitutional decision of the Federal Pact, which was valid throughout the Argentine Confederation; According to the agreement, the Constitutional Assembly was to be held in Santa Fe. The agreement was not signed by the province of Buenos Aires , as it significantly limited its authority over other provinces. Following this, Buenos Aires withdrew from the confederation, and thus, Argentina was divided into two hostile, independent states that fought for gaining dominance. [2] [84] On one side were the Federalists of the Argentine Confederation, led by Justo José de Urquiza, and on the other, the Autonomists of Buenos Aires. The civil war ended only in 1861, after the crushing victory of Buenos Aires over the Federation at the Battle of Pavon . In 1862, the liberal leader of the province of Buenos Aires, Bartolome Miter, was elected the first president of the united Argentine republic . [85] [86]

For Uruguay and Paraguay

Thanks to free navigation on the rivers of the La Plata basin, Paraguay could now hire European and Brazilian specialists who could contribute to its development. Unlimited access to the outside world also allowed the country to import more modern military technology. [38] For most of the 1950s, the Paraguayan dictator Carlos Lopez did not allow Brazilian vessels to freely navigate the Paraguay River. Lopez feared that the province of Mato Grosso could become a springboard for an attack by Brazil. These also served as leverage over the Brazilian government to recognize the territorial claims of Paraguay in the region. [87] The country had difficulty delimiting its borders with Argentina. Argentina wanted Gran Chaco to be fully part of it, but for Paraguay this requirement was unacceptable, since the country would lose more than half of its territory. [87]

The end of the Laplat war did not put an end to the confrontation in the region. Uruguay was far from the world because it was in a state of constant crisis due to the internal struggle between Blancos and Colorados. Disputes over borders, a power struggle among various political forces and attempts to establish internal and regional domination will ultimately lead to the Uruguayan War and, a little later, to the Paraguayan War . [88] [89]

Notes

- ↑ Halperín Donghi, 2007 , p. 91.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Furtado, 2000 , p. ten.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Golin, 2004 , p. 42.

- ↑ 1 2 Calmon, 2002 , p. 196.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Costa, 2003 , p. 156.

- ↑ 1 2 Vainfas, 2002 , p. 447.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Holanda, 1976 , p. 113.

- ↑ Vianna, 1994 , p. 528.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Estado-maior do Exército, 1972 , p. 546.

- ↑ 1 2 Maia, 1975 , p. 255.

- ↑ 1 2 Lyra 1, 1977 , p. 160.

- ↑ Doratioto, 2002 , p. 24.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Doratioto, 2002 , p. 26.

- ↑ Holanda, 1976 , pp. 113, 114.

- ↑ Holanda, 1976 , p. 116.

- ↑ Vainfas, 2002 , p. 448.

- ↑ 1 2 Holanda, 1976 , p. 114.

- ↑ Holanda, 1976 , p. 117.

- ↑ 1 2 Furtado, 2000 , p. 7.

- ↑ Holanda, 1976 , p. 119.

- ↑ 1 2 Holanda, 1976 , p. 120.

- ↑ Holanda, 1976 , p. 121.

- ↑ Vainfas, 2002 , p. 303.

- ↑ 1 2 Vianna, 1994 , p. 526.

- ↑ Costa, 2003 , p. 145.

- ↑ Costa, 2003 , p. 146.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Estado-maior do Exército, 1972 , p. 547.

- ↑ 1 2 Vianna, 1994 , p. 527.

- ↑ Pedrosa, 2004 , p. 110.

- ↑ Calmon, 1975 , p. 371.

- ↑ 1 2 Bueno, 2003 , p. 207.

- ↑ Lima, 1989 , p. 158.

- ↑ Pedrosa, 2004 , p. 232.

- ↑ 1 2 Pedrosa, 2004 , p. 35.

- ↑ Dolhnikoff, 2005 , p. 206.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Doratioto, 2002 , p. 28.

- ↑ 1 2 Furtado, 2000 , p. 6.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Furtado, 2000 , p. eight.

- ↑ Lyra 1, 1977 , pp. 158–162.

- ↑ Calmon, 1975 , p. 391.

- ↑ Costa, 2003 , p. 148.

- ↑ Barroso, 2000 , p. 119.

- ↑ Furtado, 2000 , p. 21.

- ↑ Calmon, 1975 , p. 390

- ↑ Holanda, 1976 , pp. 114, 115.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Lima, 1989 , p. 159.

- ↑ Golin, 2004 , p. 41.

- ↑ 1 2 Lyra 1, 1977 , p. 163.

- ↑ Calmon, 1975 , p. 387.

- ↑ Golin, 2004 , p. 35.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Maia, 1975 , p. 256.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Lyra 1, 1977 , p. 164.

- ↑ Estado-maior do Exército, 1972 , p. 548.

- ↑ Carvalho, 1976 , p. 181.

- ↑ Maia, 1975 , pp. 256, 257.

- ↑ Furtado, 2000 , p. 9.

- ↑ 1 2 Golin, 2004 , p. 22.

- ↑ Pedrosa, 2004 , p. 229.

- ↑ Carvalho, 1976 , pp. 185, 186.

- ↑ 1 2 Costa, 2003 , p. 150.

- ↑ Barroso, 2000 , p. 101.

- ↑ Golin, 2004 , p. 23.

- ↑ Golin, 2004 , p. 38.

- ↑ 1 2 Maia, 1975 , p. 257.

- ↑ Estado-maior do Exército, 1972 , p. 551.

- ↑ Barroso, 2000 , p. 112.

- ↑ 1 2 Maia, 1975 , p. 258.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Estado-maior do Exército, 1972 , p. 553.

- ↑ Costa, 2003 , pp. 155, 156.

- ↑ 1 2 Costa, 2003 , p. 158.

- ↑ 1 2 Títara, 1852 , p. 161.

- ↑ Estado-maior do Exército, 1972 , p. 554.

- ↑ Magalhães, 1978 , p. 64.

- ↑ Títara, 1852 , p. 162.

- ↑ Calmon, 1975 , p. 407.

- ↑ 1 2 Golin, 2004 , p. 43.

- ↑ Doratioto, 2009 , p. 80.

- ↑ Scheina, 2003 , p. 123.

- ↑ Golin, 2004 , pp. 42, 43.

- ↑ Calmon, 2002 , p. 195.

- ↑ Lyra 1, 1977 , p. 200.

- ↑ Bueno, 2003 , p. 196.

- ↑ Lyra 1, 1977 , p. 199.

- ↑ Doratioto, 2002 , p. 29.

- ↑ Furtado, 2000 , p. 17.

- ↑ Pedrosa, 2004 , p. 168.

- ↑ 1 2 Furtado, 2000 , p. 14.

- ↑ Doratioto, 2002 , pp. 95, 96.

- ↑ Furtado, 2000 , p. 13.

Literature

- Barman, Roderick J. Citizen Emperor: Pedro II and the Making of Brazil, 1825–1891. - Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999. - ISBN 978-0-8047-3510-0 .

- Barroso, Gustavo. Guerra do Rosas: 1851–1852: [] . - Fortaleza: SECULT, 2000.

- Bueno, Eduardo. Brasil: Uma História: [] . - São Paulo: Ática, 2003 .-- ISBN 978-85-08-08213-1 .

- Calmon, Pedro. História de D. Pedro II: [] . - Rio de Janeiro: J. Olympio, 1975.

- Calmon, Pedro. História da Civilização Brasileira: [] . - Brasília: Senado Federal, 2002.

- Carvalho, Affonso. Caxias: [] . - Brasília: Biblioteca do Exército, 1976.

- Costa, Virgílio Pereira da Silva. Duque de Caxias: [] . - São Paulo: Editora Três, 2003.

- Dolhnikoff, Miriam. Pacto imperial: origens do federalismo no Brasil do século XIX: [] . - São Paulo: Globo, 2005 .-- ISBN 978-85-250-4039-8 .

- Doratioto, Francisco. Maldita Guerra: Nova história da Guerra do Paraguai: [] . - São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002 .-- ISBN 978-85-359-0224-2 .

- Doratioto, Francisco. {{{title}}} (port.) // Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional. - Rio de Janeiro: SABIN, 2009 .-- T. 4 , No. 41 .

- Estado-maior do Exército. História do Exército Brasileiro: Perfil militar de um povo: [] . - Brasília: Instituto Nacional do Livro, 1972. - Vol. 2.

- Furtado, Joaci Pereira. A Guerra do Paraguai (1864–1870): [] . - São Paulo: Saraiva, 2000 .-- ISBN 978-85-02-03102-9 .

- Golin, Tau. A Fronteira: [] . - Porto Alegre: L&PM Editores, 2004. - Vol. 2. - ISBN 978-85-254-1438-0 .

- Halperín Donghi, Tulio. The Contemporary History of Latin America. - Durham: Duke University Press, 2007 .-- ISBN 978-08-2231-374-8 .

- Holanda, Sérgio Buarque de. História Geral da Civilização Brasileira (II): [] . - DIFEL / Difusão Editorial SA, 1976. - Vol. 3.

- Lewis, Daniel K. The history of Argentina. - New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001 .-- ISBN 978-1-4039-6254-6 .

- Lima, Manuel de Oliveira. O Império brasileiro: [] . - Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1989 .-- ISBN 978-85-319-0517-9 .

- Lynch, John. Argentine caudillo: Juan Manuel de Rosas. - Lanham: SR Books, 2001. - ISBN 978-0-8420-2898-1 .

- Lyra, Heitor. História de Dom Pedro II (1825–1891): Ascenção (1825–1870): [] . - Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1977 .-- Vol. one.

- Lyra, Heitor. História de Dom Pedro II (1825–1891): Fastígio (1870–1880): [] . - Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1977 .-- Vol. 2.

- Magalhães, João Batista. Osório: síntese de seu perfil histórico: [] . - Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército, 1978.

- Maia, João do Prado. A Marinha de Guerra do Brasil na Colônia e no Império: [] . - 2nd. - Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Editora Cátedra, 1975.

- Palmerlee, Danny. Argentina. - 6th. - Lonely Planet, 2008 .-- ISBN 978-1-74104-702-8 .

- Pedrosa, JF Maya. A Catástrofe dos Erros: [] . - Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército, 2004 .-- ISBN 978-85-7011-352-8 .

- Scheina, Robert L. Latin America's Wars: The age of the caudillo, 1791–1899. - Dulles: Brassey's, 2003 .-- ISBN 978-1-57488-450-0 .

- Títara, Ladislau dos Santos. Memórias do grande exército alliado libertador do Sul da América : [] . - Rio Grande do Sul: Tipografia de B. Berlink, 1852.

- Vainfas, Ronaldo. Dicionário do Brasil Imperial: [] . - Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 2002 .-- ISBN 978-85-7302-441-8 .

- Vianna, Hélio. História do Brasil: período colonial, monarquia e república: [] . - 15th. - São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1994.