The leader of the USSR, Joseph Stalin, described 1929 as the year of the "Great Breakthrough . " This year, the country has undergone significant changes in its domestic political and economic course, associated with the abandonment of the NEP , forced collectivization and industrialization .

In the same way, in 1929 the state’s policy regarding religion changed. Since that time, the Soviet state has finally stopped “flirting” with any faiths. The “religious NEP”, characterized by partial liberalization, was curtailed, and toughening of the anti-religious struggle began. Moreover, the attitude of the state towards religion was becoming tougher and tougher every year.

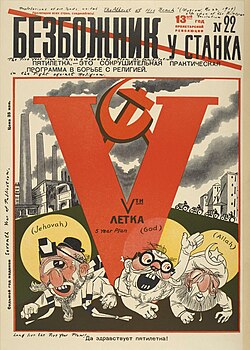

In the fight against religion, propaganda gradually began to fade into the background, giving way to an open struggle with religious organizations and repressions against believers. It is no coincidence that the period from 1932 to 1937 in the history of the church was called the “ godless five-year plan ”.

Content

- 1 Propaganda

- 2 Fight against religious organizations

- 3 Repression against believers

- 4 Theory of the “Church Thaw” of 1939

- 5 Religion and Soviet power in the new territories of the USSR (1939-1941)

- 6 See also

- 7 notes

- 8 Literature

Propaganda

The late 1920s - early 1930s were peak in the activities of the All-Union Anti-Religious Society “ Union of Atheists ”. A variety of anti-religious publications were published under the auspices of this organization (the newspaper “Atheist” , magazines “Atheist”, “Anti-religious”, “Militant Atheism”, “Village Atheist”, “Young Atheist” and others, published in various languages of the peoples of the USSR), mass events - lectures, demonstrations, disputes, "anti-religious Easter", etc. The society had tens of thousands of primary cells in factories, factories, on collective farms, in educational institutions. By 1936, the number of organizations exceeded 5 million people, in the detachments of young atheists were more than 2 million children [1] .

The state provided a number of benefits to activists of this organization, additional educational and training opportunities, and free trips. For some of them (lecturers, agitators, employees of the administrative apparatus), atheism has become a profession.

At the II Congress of the Union of Atheists in 1929, 1,200 delegates arrived. Bukharin , Lunacharsky , Maxim Gorky [2] , Demyan Bedny , Vladimir Mayakovsky delivered speeches at the congress. The congress showed an irreconcilable attitude towards religion. For example, the poet V. Mayakovsky ended his speech with an appeal: “Comrades, usually their pre-revolutionary meetings and congresses ended with an appeal“ with God, ”- today the congress will end with the words“ to God. ” This is the slogan of today's writer ” [3] . The congress renamed the organization the Union of Militant Atheists.

The results of the congress dispersed to the regions of the country. “The anti-religious front is currently a fighting front, and we must expand our work widely ,” the “About anti-religious propaganda” [4] said in the circular of the Vladivostok city committee of the CPSU (b) of December 13, 1929.

Baptist presbyter G.P. Vince, according to his mother’s recollections, described the holding of a “godless Easter”:

On Easter Sunday in 1928, several lorries slowly drove up to the prayer houses of the Baptists and Molokans, which were located on the same street in the center of Blagoveshchensk. There were a lot of young people in cars, dressed in colorful buffoonery: some depicted demons with rag tails, others depicted white angels with wings, and one buffoon, dressed in a black hoodie, depicted a devil with horns. They were also dressed as Orthodox priests in full vestments, and some were dressed as monks and nuns in long black robes. They all shouted loudly, grimaced and danced, the sides of the trucks were lowered and upholstered in red cloth.

Cars drove slowly around the city, accompanied by a large crowd of Komsomol members, boys and girls, already in ordinary clothes. They all laughed out loud, shouting anti-religious slogans: “There is no God!”, “Religion is opium for the people!”, “Down with God!”. At first, this procession stopped at the Molokan prayer house, a massive stone building with a capacity of 1,500 people. But the Molokan meeting had ended by that time; everyone had already gone home. The participants in the procession shouted several anti-religious slogans in front of the empty building and moved on. The Baptist house of worship was also large, with a capacity for 1000 people. It was built thoroughly, from large thick logs, back in 1910. The cars stopped, and part of the raging crowd burst into the courtyard of the prayer house with loud cries: “Baptists! Stop praying! Come to the dispute! There is no God! ”But no one came out, only the singing of the Easter hymn was heard:“ He is alive! He is alive! He himself trampled death ” [5] !

However, with all the pressure, anti-religious propaganda did not bear the desired fruit. In the 1937 census, 1/3 of the townspeople and 2/3 of the rural population (non-anonymously) called themselves believers [6] . According to the church historian, Archpriest Vladislav Tsypin, it was the census results that entailed the Chekist “purge” of the ranks of the “Union of Militant Atheists” [6] . However, starting from 1932-1933, the activities of this organization steadily declined: the authorities needed it less and less, preferring direct repressions to "enlightening" methods of fighting religion.

Fighting Religious Organizations

The main methods of combating religious organizations were the confiscation of temple buildings, houses of worship, mosques, synagogues; deprivation of religious communities and unions of state registration, the closure of educational institutions and publications, as well as the actual ban on any activity outside the church walls.

Until 1930, the closure of any church required the consent of the Commission for Religious Affairs under the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the RSFSR [7] . This significantly impeded the mass liquidation of prayer buildings.

In 1929 and the beginning of 1930, a number of normative acts were adopted that seriously limited the rights of religious organizations and clergy and gave local authorities the right to close churches. After this, the campaign to close and demolish religious buildings became widespread.

On April 8, 1929, the Decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR “On Religious Associations” [8] was issued. This document (with additions and amendments introduced later) was the main legal act regulating religious life in the USSR until the very end of Soviet power .

The new document limited the activities of religious ministers to the walls of temples, monasteries, houses of prayer, mosques and synagogues, as well as the place of residence of believers. It was forbidden to create mutual assistance cash desks, cooperatives, production associations and generally use the property at their disposal for any other purpose than satisfying religious needs; provide material support to its members; organize specially children’s, youth’s, women’s prayer and other gatherings, as well as general biblical, literary, needlework, labor, religious studies, etc. meetings, groups, circles, departments, as well as arrange excursions and playgrounds, open libraries and reading rooms, organize sanatoriums and medical care [8] .

In May 1929, at the XIV All-Russian Congress of Soviets, a new version of Article 4 of the Constitution of the RSFSR was adopted: instead of “freedom of religious and anti-religious propaganda,” they recognized “freedom of religious practice and anti-religious propaganda,” which placed believers in an unequal position with other citizens. Finally, on May 21, 1929, the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR adopted a resolution “On the characteristics of kulak farms in which the Labor Code should apply”, in which the economy belonging to the clergy was declared one of the signs of the kulak economy [9] .

On June 8, 1929, the People’s Commissariat of Labor of the USSR, circular No. 188 “On the Non-Proliferation of Labor Legislation for Persons Serving Religious Cults,” stipulated that persons “serving all kinds of religious cults regardless of forms of service, at least receiving remuneration (for example: , regents, psalmists, clerical workers in the Church Councils, etc.) ”social insurance, as well as pensions (except for guards, stokers, people engaged in the repair and construction of religious buildings, are not covered) ice, as well as teachers who taught in pre-revolutionary times in church schools, if they also taught non-religious subjects) [10] .

The circular of the NKVD of the RSFSR “On the responsibility of worshipers for religious rites before registering the relevant events with the civil registry offices” of October 14, 1929 forbade worshipers to perform wedding ceremonies on persons under the age of marriage, to issue certificates of worship (baptism, circumcision, burial , weddings, etc.); For violation of these rules, in accordance with Article 125 of the Criminal Code (“Assignment of religious, church or other administrative, judicial or other public legal functions and the rights of legal entities”), forced labor for a period of up to 6 months or a fine of up to 700 rubles [11] .

On January 26, 1930, the Commission on Religious Issues under the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the RSFSR changed the decision-making procedure for closing churches. From now on, the final decision on the liquidation of the prayer building was made by the regional and regional executive committees (for the autonomous republics that do not have divisions, the previous order was preserved), and believers received only the right to appeal their decisions to the Commission on Religious Issues [12] . From this moment begins the mass closure and destruction of religious buildings.

On February 11, 1930, the CEC and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR issued a resolution “On the Fight against Counter-Revolutionary Elements in the Leading Bodies of Religious Associations,” which proposed, when registering religious associations, to exclude from them “kulaks, deprived persons and other persons hostile to Soviet power” and to prevent further penetration of these bodies of these persons [13] .

Soon, mass protests began against the persecution of believers, which in some cases combined with protests against forced collectivization . Only in 1930 in the USSR were recorded 1,487 mass performances on religious grounds (most of them in March 1930 - 514 performances and in April 1930 - 391 performances) [14] . After the publication of an article by I. V. Stalin, “ Vertigo from success, ” the authorities made some concessions. For example, on October 13, 1930, the norm that equated priests with fists was canceled [9] .

As a result of the campaign to close churches, houses of worship, mosques and synagogues, for example, in the Leningrad Region, out of 2165 religious buildings that existed before the revolution, 1207 were closed in 1917-1935. Of the 421 buildings, 316 were closed in Leningrad, in this city in the former The “House of Salvation" of evangelical Christians houses the House of the Atheist. In the Far East for three years (1929-1932), out of 193 Baptist communities, 44 remained, out of 118 communities of evangelical Christians - 42 [15] . According to the Kostroma newspaper Severnaya Pravda (January 18, 1930, No. 18), out of 37 Kostroma Orthodox churches, 14 were closed by 1930, and another 19 were planned to be closed during 1930. It was planned to give one of the churches to an anti-religious museum [16] .

As the historian Tatyana Nikolskaya noted, if in Orthodoxy the existence of the community often ceased with the closure of the church, then Protestants often simply "went underground" and began to hide the places of their meetings. In this connection, cells of the “Union of Militant Atheists” on the ground were used to identify sectarians [17] .

On December 31, 1929, the Commission on Religious Issues under the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee adopted a law on the regulation of bell ringing, which was supposed to be implemented “in order to satisfy the requests of citizens who became especially numerous in connection with the transition to a continuous production week, on the termination or settlement of bell ringing, which interferes with both work and leisure for workers ”, but, based on political expediency, only“ in those cities and urban-type settlements, as well as large commercial and industrial villages ah, where the majority of enterprises have moved or are moving to a continuous production week. ” The bells were completely banned - ringing all the bells. On May 16, 1931, the Commission on Religious Issues under the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee decided “upon the provision of a detailed report to the Commission and the Rudmetaltorg to instruct Comrade Smidovich to enter the decision-making bodies with a petition to allow the removal of bells from prayer buildings, in which the bell ringing was stopped”. The bell bronze was supposed to be used for making small coins, without making this fact publicly public - the official slogan was “Let us melt the bells into wires!”. [18] . Melting bells was carried out as planned. So, on October 8, 1930, the Supreme Economic Council of the USSR submitted to the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR a proposal for the seizure of bells in cities “where bell ringing is forbidden”, and it was proposed to confiscate “no less than 25 thousand tons in the October-December 1930 quarter and January-June 1931 scrap bells ” [19] . Then came the secret decree of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR of November 14, 1930 No. 122.877s, sent out to the chairmen of the regional (oblast) executive committees, the chairmen of the Council of People's Commissars of the Autonomous Republics and the executive committees of the autonomous regions, which provided for “removing excessive bells” under the pretext of “the needs of our industry ( first of all, for minting a small bargaining chip, which is still minted from imported copper) ” [20] . The document provided for the removal of bells only in cities and workers' settlements, and it was specified that "dropping bells from bells should be resorted to only in cases of extreme necessity" [21] . On the ground, authorities seized not only bells. For example, in the Western Region , a decree was issued ordering from city cemeteries to transfer to scrap “all unowned grave metal lattices and monuments, with the exception of those that are placed on the graves of prominent figures in the field of social and political work, revolutionary movement, science, art, as well as those tombstones, which in themselves are of significant historical and artistic value ” [22] . The following figures indicate the extent of the seizure of bells in the field. In the Western Region, on October 1, 1929, the total weight of the bells was 3652 tons, and on January 1, 1935, only 692 tons [23] .

Since the mid-1930s the removal of bells was usually carried out in the order without any formal meeting of residents on the issue of banning bell ringing. Sometimes such actions led to peasant riots (on January 20-24, 1935 in the village of Sumoryevo of the Voznesensky district of the Gorky Territory; on June 27, 1935 in the village of Omutsky of the Suzdal District, on June 29, 1937 in the village of Gubtsevo of the Gus-Khrustalny District and other). [24] .

During the collapse of the NEP , the Bolsheviks decided to liquidate private enterprise by taxing in such a way that commercial activity would lose all meaning or bring significant loss. At the same time, religious organizations were equated with commercial enterprises, and clergy - with entrepreneurs. For non-payment of tax, clergymen could be arrested, and their parishes closed [25] .

The historian Dmitry Pospelovsky cites as an illustration the letter from the daughter of the arrested priest M. P. Krylova, preserved in the archives, addressed to M. I. Kalinin (11/19/1930): "The father-priest of the Borshchiv church ... Kostroma district ... was arrested more than a month ago." No reasons were reported, no information. The family is taken away, even the sheepskin coat was taken away. “When I, after the atrocities committed against us, asked Chairman Rogov what to do, he replied:“ It’s best to go to a concubine to some guy. ”A sick mother, a sick teenage sister were left without property and livelihood, brother of 10 years and a writing letter, a 24-year-old girl, judging by her letter, they were doomed to starvation.

The district prosecutor’s response to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee’s request in this case is characteristic: “Krylov was arrested and sent to a concentration camp for 5 years by order of ... three OGPUs ... correctly,” because he agitated peasants not to join collective farms “introduced by Jews who want to close Russian churches” [26 ] .

In 1928-1929, Protestant denominational magazines ( Baptist , Baptist of Ukraine, Evangelist, Evangelist ) ceased to appear. In 1929, the Bible courses organized by I. S. Prokhanov in Leningrad ceased to exist. In the same year, the Federal Union of Baptists of the USSR was closed. It was later restored for a while, but after the arrest of the Baptist leaders in March 1935 it was finally closed. However, the All-Union Council of Evangelical Christians, despite periodic arrests of leaders and interruptions in work, nevertheless "continued to eke out a miserable existence" , as L. N. Mitrokhin put it [27] .

A similar situation was observed in the Orthodox Church, where in May 1935 the Provisional Patriarchal Holy Synod , headed by Deputy Patriarchal Locum Tenens Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky) , was forced to "self-destruct". Two weeks earlier, the renovated Holy Synod “self-destructed”. In 1937, as a result of mass repressions against the clergy, the administrative apparatus of the church was actually destroyed (for details, see the section "Repressions against the clergy and believers).

Repression against Believers

Since the late 1920s, a wave of landings and executions of clergy and religious activists of all faiths began to increase. The Government Decree “On the Fight against Counter-Revolutionary Elements in the Leading Bodies of Religious Associations”, adopted on February 15, 1930, called for local authorities to tighten control over the leaders of religious communities and exclude those “hostile to the Soviet system” from the asset. So, the Far Eastern State Security Directorate of the NKVD in the 1930s formulated the main reasons why “churchmen and sectarians” can be convicted: religious propaganda among the population; penetration into Soviet institutions of cities, into village councils; opposition to the cultural and political events of the party and the state; agitation against the tax policy of the state; the spread of counter-revolutionary, provocative rumors; connection with foreign counterrevolutionary white-emigrant organizations and foreign intelligence services, etc. [28] .

The peak of repression against the "religious" occurred in the period of the Great Terror of 1937-1938. In 1937, the NKVD secret operational order No. 00447 was issued , according to which “clergy and sectarian activists” were declared “anti-Soviet elements” to be repressed. The implementation of this order began in August 1937. However, at the plenum of the Central Committee of the CPSU (B.) In October 1937, a discussion arose about the danger of religious organizations for the upcoming elections to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. In this connection, the plenum adopted the NKVD directive prescribing "in the coming days to ensure the operational rout of the church and sectarian counter-revolutionary assets" [29] .

The intensification of persecution of believers was carried out under the personal control of Stalin. So, on November 13, 1937, L.Z. Mehlis forwarded to Stalin a letter from the editor of the newspaper Zvezda about the harmful influence of the church in Belarus, and Stalin wrote a resolution: “T. Yezhov . It would be necessary to trim the gentlemen of the churchmen ” [30] . In response, Yezhov sent Stalin extensive material on the progress of repressions against “clergy and sectarians” in the field. According to Yezhov, between August and November 1937, 31,359 “churchmen and sectarians” were arrested, of whom 166 were metropolitans and bishops, 9116 were priests, 2173 were monks, and 2173 were “church-sectarian kulak assets”. 13671 people were sentenced to be shot, including 81 bishops, 4629 priests, 934 monks, and “church-sectarian kulak asset” - 7004 [31] .

In his commentary on these figures, Yezhov wrote: “As a result of our operational activities, the episcopate of the Orthodox Church was almost completely eliminated, which greatly weakened and disorganized the church. <...> The number of priests and preachers was halved, which should also contribute to the decomposition of the church and sectarians . " According to Yezhov, Orthodox “clergymen” (Tikhonov’s, Renovationists, Gregorians) supposedly now acted in concert with the “sectarians”, setting “the task of creating a united anti-Soviet front”. The unpublished part of Yezhov’s note contained proposals to saturate the surviving religious structures with KGB agents, apparently approved by Stalin [31] .

Continuous arrests, landings and executions dragged on throughout the entire period 1937-1938. Due to the fact that the bulk of archival documents on repressions are currently inaccessible to researchers, accurate data on the number of victims among believers are still not available. According to the calculations of the historian Dmitry Pospelovsky (having data on the proportion of the repressed among the priests of Leningrad, he interpolated this indicator for the whole country), over a decade (1931-1941) in Orthodoxy “80 to 85% of priests were liquidated or arrested, that is, more than 45 thousand " (we are talking about both the servants of the Patriarchal Church and the Renovationists) [32] . As for the North-West of the RSFSR (Leningrad Oblast within the borders of 1937 and Karelia), among the clergy of the Moscow Patriarchate who served in parishes at the beginning of 1937, 804 people are known to be executed in 1937-1938, which is 63% of the total and 80% of those whose biographies were tracked [33] .

Until now, there is not even a rough estimate of the number of victims among Protestants. Martyrologists published or published in different regions of the country contain incomplete information. For example, the list of victims of Stalinist repressions among evangelical Christians and Baptists of the Primorsky Territory , cited in the book by Andrei Dementyev “Aven-Jezer: Evangelical Movement in Primorye 1898-1990” (the list is far from complete, as the author warns), includes 108 person. Of these, 88 were executed by shooting. This amounted to 5-10% of the total number of evangelical Christians and Baptists in this region [34] .

However, despite the repression, the majority of the population of the USSR in the late 1930s were believers. The 1937 census showed that out of 98.4 million residents of the Soviet Union aged 16 years and over 55.3 million people called themselves believers (of which 41.6 million considered themselves Orthodox) [35] .

The 1939 Church Thaw Theory

In 1999, the magazine Our Contemporary , as well as some communist and “patriotic” media, published statements that already in 1939 the course of the Stalinist state towards the Orthodox religion and the Church was radically “warmed up”. The basis for such a statement was a series of party and state documents (including “An extract from the minutes No. 88 of the meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks of November 11, 1939”), which were allegedly discovered by journalist V. M. Markov when publishing memoirs of USSR Marshal D. T. Yazova . This information was repeatedly voiced by the so-called "Orthodox Stalinists" (including some priests of the Russian Orthodox Church). Later, information from journalism fell into some more serious scientific and historical research [36] .

However, this statement is refuted by a number of authoritative historians. For example, academician L. N. Mitrokhin , citing the text of the “Anti-Religious Textbook” published in 1940, argued: “the desire of the native authorities to finally“ finish off the counter-revolutionary clergy “... has been fully preserved” [27] .

Another famous historian, I. A. Kurlandsky , in his book “Stalin, Power, Religion,” devoted a whole chapter of 27 pages to this issue. Courlandsky cited the history of modern publications on the “thaw” of 1939 and, based on source analysis, concluded that the statements were not based on real historical documents, but on “crude fakes” [37] . In his opinion, these materials “ are forgeries roughly fabricated in the late 1990s to achieve dirty political goals - the formation and implementation of the myth of Stalin’s disposition towards the Church and the Orthodox religion, creation of positive images of the“ Orthodox ”Stalin and the“ patriotic “Stalinist leadership. Accordingly, all the plots in historiography, in textbooks and anthologies, which speak of a radical change in the state-church course before the war, are untrue ” [30] .

Religion and Soviet Power in the New Territories of the USSR (1939-1941)

After the outbreak of World War II, Western Ukraine , Western Belarus , Bessarabia , and the Baltic republics were annexed to the USSR in 1939-1940. They preserved many active religious parishes - Orthodox, Protestant, Catholic and Jewish.

So only on the territory of the Eastern Voivodships of Poland, annexed (except for the Vilno Territory ) to the USSR, according to the Polish statistical yearbook in 1939, the following population groups lived [38] :

- 4734.9 thousand Catholics (36.4% of the population);

- 3514.7 thousand Orthodox (26.9% of the population);

- 3273.3 thousand Greek Catholics (25.1% of the population);

- 1269.1 thousand Judaists (9.7% of the population);

- 105.5 thousand evangelists;

- 87.9 thousand Christians of other confessions.

- 17.9 thousand atheists and people professing other religions.

From these figures it can be seen that in 1939, millions of believers replenished the Soviet population. I had to reckon with them.

In particular, the Moscow Patriarchate got the opportunity to consecrate several bishops for these territories in 1940 - early 1941, while in the USSR only two episcopal departments remained in the pre-war borders - in Moscow and Leningrad (a significant part of the episcopate was destroyed, with the exception of some bishops, received camp terms or who lived “outside the state” as private individuals) .

From the first weeks after the accession, the Soviet government began to fight religion in new territories: through taxes, a ban on religious education, the removal of religious buildings and massive atheistic propaganda. So in Lithuania, on July 1, 1940, religion classes in schools were banned (with the dismissal of teachers of religious disciplines), although educational institutions in this republic were nationalized only on August 8 and 24, 1940 [39] . On July 16, 1940, the Faculty of Theology and Philosophy of Vytautas the Great University was closed [40] .

Atheistic propaganda was launched on new lands in 1939-1941. In Western Belarus, it began to lead the Union of Militant Atheists and Party Committees in fact since May 1940 [41] . The main form of anti-religious propaganda was reports and lectures, the topics of which were selected and approved by the district party committees on the recommendations of the Central Council of the Union of Militant Atheists [42] . Until February 1941, anti-religious lectures were delivered mainly by the “Easterners” (scientists, university teachers, lecturers of their Union of Militant Atheists, Communists, Komsomol members), and they taught them only in Russian [43] . The first months of anti-religious lectures in Western Belarus were free (in the USSR, a fee was introduced on November 14, 1938 by a decision of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks) [43] . In June 1940, lectures became paid - the decision of the Central Committee of the CPSU (b) was extended to Western Belarus [43] . Antireligious lectures were usually held before major religious holidays. For example, before Orthodox Easter, they gave lectures “On the Origin and Class Essence of Religion,” “The Origin and Harm of Easter,” on Jewish Jewish holidays, “Where did Jewish Religious Holidays come from,” “Religious holidays are a relic of capitalism” [43] . Mostly anti-religious propaganda was carried out in regional and district centers and was practically absent in rural areas [43] . A sale of anti-religious literature was also organized.

On February 10, 1941, the Decree of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Bolsheviks of Belarus “On the state of anti-religious propaganda in the western regions of the BSSR” was issued, which sharply tightened anti-religious propaganda, opening its new stage in Western Belarus [41] . The resolution introduced a number of innovations:

- The oblast, city, and rayon party committees were obliged to select candidates for anti-religious lecturers from the population of Western Belarus and send them to courses organized by the oblast party committees.

Since March 1941, the number of anti-religious lectures in the villages of Western Belarus has increased [44] . Authorities gave instructions on organizing “anti-religious library”, reading anti-religious magazines, creating “corners of atheists” at libraries [45] .

The Soviet regime of labor and rest, introduced on new lands, objectively impeded the observance of religious holidays. On August 7, 1940 (including on Western lands), a 7-day working week was introduced with a floating day off, which, for example, made it impossible for local Jews to celebrate Shabbat [46] .

In 1939-1941, religious buildings were taken from believers on new lands. Soviet religious schools were located in some religious buildings - the introduction of universal school education required new facilities [47] . In addition, all religious subjects were removed from schools in the new lands, and the children themselves were obliged to study, including during religious holidays. In 1939-1941, an aggressive anti-religious policy was conducted in Western Belarus: religious schools were banned, atheism lessons were introduced in general educational institutions, synagogues and houses of worship were taken from believers [48] .

See also

- Stalinist repression of evangelical Christians and Baptists

- Destruction of monastery and church cemeteries

- Khrushchev anti-religious campaign

Notes

- ↑ Anniversary evening of the Central Council of the SVB of February 7, 1936 // GARF F. R-5407 op. 1 d. 105 l. 15. Cit. by: Nikolskaya T.K. Russian Protestantism and State Power in 1905-1991. - St. Petersburg: Publishing House of the European University, 2009. - S. 106. ISBN 978-5-94380-081-8

- ↑ Speech by M. Gorky at the opening of the II All-Union Congress of Militant Atheists on June 10, 1929 (inaccessible link) . Date of treatment September 19, 2013. Archived September 21, 2013.

- ↑ Speech by V.V. Mayakovsky at the II All-Union Congress of Militant Atheists (inaccessible link) . Date of treatment September 19, 2013. Archived September 21, 2013.

- ↑ GAPK (State Archive of Primorsky Territory) F. P-3 op. 1, d. 175, l. 204. Cit. by Dementiev A. Aven-Jezer: Gospel movement in Primorye 1898-1990 . - Vladivostok: Russian Island, 2011 .-- S. 93. - ISBN 978-5-93577-054-2 . Archived March 6, 2016 on Wayback Machine

- ↑ Vince G.P. The Path of Allegiance

- ↑ 1 2 Tsypin V., prot. History of the Russian Church. S. 248

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 80.

- ↑ 1 2 Decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, SNK of the RSFSR of 08.04.1929 “On Religious Associations” Archived copy of February 2, 2017 on the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 1 2 Batchenko, 2015 , p. 98.

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 45.

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 45–46.

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 57, 80-81.

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 58.

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 143.

- ↑ Nikolskaya, 2009 , p. 96.

- ↑ Nikolskaya, 2009 , p. 96–97.

- ↑ Nikolskaya, 2009 , p. 98.

- ↑ Ershov A. L. Church on the Vladimir land in the 1930s / A. L. Ershov. - Vladimir: Kaleidoscope, 2011 .-- S. 79; GARF. F. P-5263. Op. 1. D. 5. L. 2; D. 2.L. 9, 12-13; D. 9.L. 14.

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 61.

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 61-62.

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 62.

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 63.

- ↑ Batchenko, 2015 , p. 96.

- ↑ Ershov A. L. Church on the Vladimir land in the 1930s / A. L. Ershov. - Vladimir: Kaleidoscope, 2011 .-- S. 152-159.

- ↑ Pospelovsky, 1995 , p. 158.

- ↑ Pospelovsky, 1995 , p. 158-159.

- ↑ 1 2 Mitrokhin L.N. Baptism: history and modernity (philosophical and sociological essays). - SPb .: RHGI , 1997. - S. 396

- ↑ Potapova N.V. - Religious life of Sakhalin: In the second half of the XIX - beginning of the XXI centuries.

- ↑ Courland, 2011 , p. 516.

- ↑ 1 2 Courland, 2011 , p. 549.

- ↑ 1 2 Courland, 2011 , p. 517.

- ↑ Pospelovsky, 1995 , p. 170.

- ↑ Alexy (Simansky), Metropolitan of Leningrad. Alphabetical list of clergy of the Leningrad Region on May 1, 1937. Publication by A. A. Bovkalo and A. K. Galkin. St. Petersburg: Prince Vladimir Cathedral, 2014.S. 9

- ↑ Dementiev A. “Aven-Jezer: Gospel Movement in Primorye, 1898-1990.” pp. 113-141

- ↑ Emelyanov N.E., Khaylova O.I. Persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church (1917-1950s) // Russia and the modern world . - 2008. - No. 4 (61). - S. 125

- ↑ Courland, 2011 , p. 523-527.

- ↑ Courland, 2011 , p. 537.

- ↑ Tsymbal A.G. The situation of the Orthodox Church in Western Belarus in 1939-1941 // Western Belarus and Western Ukraine in 1939-1941: people, events, documents. - St. Petersburg: Aletheya, 2011 .-- C. 338-339.

- ↑ Gorin A. A. Transformation of the infrastructure of education and science of Lithuania at the initial stage of its Sovietization (1940-1941) // Bulletin of the Catherine Institute. - 2016. - No. 1 (33). - S. 14.

- ↑ Gorin A. A. Transformation of the infrastructure of education and science of Lithuania at the initial stage of its Sovietization (1940-1941) // Bulletin of the Catherine Institute. - 2016. - No. 1 (33). - S. 15.

- ↑ 1 2 Kharchenko O. P. Organization and conduct of anti-religious and propaganda work in the western regions of Belarus (September 1939 - June 1941) // State, religion, Church in Russia and abroad. - 2011. - T. 29. - No. 3-4. - S. 420.

- ↑ Harchenko O. P. Organization and conduct of anti-religious and propaganda work in the western regions of Belarus (September 1939 - June 1941) // State, religion, Church in Russia and abroad. - 2011. - T. 29. - No. 3-4. - S. 420-421.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Kharchenko O. P. Organization and conduct of anti-religious and propaganda work in the western regions of Belarus (September 1939 - June 1941) // State, religion, Church in Russia and abroad. - 2011. - T. 29. - No. 3-4. - S. 422.

- ↑ Harchenko O. P. Organization and conduct of anti-religious and propaganda work in the western regions of Belarus (September 1939 - June 1941) // State, religion, Church in Russia and abroad. - 2011. - T. 29. - No. 3-4. - S. 422-423.

- ↑ Harchenko O. P. Organization and conduct of anti-religious and propaganda work in the western regions of Belarus (September 1939 - June 1941) // State, religion, Church in Russia and abroad. - 2011. - T. 29. - No. 3-4. - S. 423-424.

- ↑ Karpenkina Ya. V. Jewish population and economic transformations in Western Belarus, 1939-1940 // Bulletin of the Nizhny Novgorod University. N.I. Lobachevsky. - 2016. - No. 4. - S. 29.

- ↑ Karpenkina Y. V. Sovietizing Jews: From the History of Soviet Educational Policy in Western Belarus, 1939-1941 // Russian History. - 2017. - No. 5. - S. 158.

- ↑ Karpenkina Ya. V. It is forbidden to prohibit: Soviet religious policy in Western Belarus in relation to Judaism in 1939-1941 // TIROSH - Works on Judaica / Collection of articles. Ser. “Judaica Rossica” - M.: Sefer, 2018. - P. 168.

Literature

- Batchenko V.S. Peasant resistance to state anti-religious policy in 1929-1931. (based on materials from the Western region). The dissertation for the degree of candidate of historical sciences . - Smolensk, 2015 .-- 259 p.

- Kurlandsky I. A. Stalin, power, religion (religious and church factors in the internal politics of the Soviet state in 1922–1953). - M .: Kuchkovo field, 2011 .-- 720 p. - ISBN 978-5-9950-0150-8 .

- Nikolskaya T.K. Russian Protestantism and State Power in 1905-1991. - SPb. : Publishing house of the European University , 2009. - 356 p. - (Territories of history; Issue 2). - ISBN 978-5-94380-081-8 .

- Pospelovsky D.V. Russian Orthodox Church in the XX century . - M .: Republic , 1995 .-- 511 p. - ISBN 5-250-02501-3 .