Horses of Przewalski [1] ( lat. Equus przewalskii caballus , lat. Equus ferus przewalskii , Mong. Takh ) - a species or subspecies of a wild horse that lives in Asia . Some taxonomists consider Equus przewalskii as a separate species, primarily because of the different normal number of chromosomes in domestic and Przewalski horses. While the domestic horse and even all but the Przhevalsky horse have species of the “horse” subgenus of the “horse” genus, which unites all the living species of the Horse family (and the disappeared tarpan ) have 64 chromosomes , of Przhevalsky’s horse they have 66 chromosomes . But it is the domestic horse and Przhevalsky’s horse that cross freely and produce prolific offspring, while the males of all other hybridizations of the horse species are always barren. [2] All modern Przhevalsky horses originated not only from 11 wild Przewalski horses, but also from one domestic horse; therefore, many consider Przhevalsky’s horse not as a species, but as a subspecies of the species “ domestic horse ” or “ wild horse ”, considering different the number of chromosomes of horses and Przewalski's horses by a random mutation. [3] Due to the different number of chromosomes in the normal karyotype, it seems unbelievable the consensus that the Przewalski horse was the main ancestor of the domestic horse. [4] On the contrary, it is very likely that all other existing species of the horse genus, especially horse subgenus and donkeys, occurred as a result of a reduction in the number of chromosomes of Przewalski's horse. The zebra subgenus has 44 chromosomes, the subgenus African donkey has 62 chromosomes, the subgenus Asian donkey has 54 chromosomes. The tail of Przhevalsky’s horses is not horse’s, but typically donkey’s: the root has a short hair and a long hair at the end, which is almost unbelievable with a random mutation. From the withers to the tail - a dark strip, like donkeys. There are signs of zebroidity on the legs. Therefore, Przhevalsky’s horses are often considered not only a separate species, but also the only representative of a special subgenus of the horse genus, and, as Academician V.V. Zalensky first postulated, closest to the common ancestor of all living species of the horse genus. [five]

| Przewalski's horse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Przewalski's Horse at the Warsaw Zoo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International Scientific Name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Equus ferus przewalskii Poliakov, 1881 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

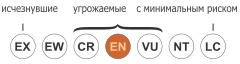

| Security status | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to paleogenetics, Przhevalsky’s horses are feral descendants of Botai horses [6] [7] . At the same time, the boatmen, possessing the skills of taming horses, did not select [8] [9] . The line leading to modern domesticated horses (DOM2) branches off from Przewalski's horse 43.8 thousand liters. n About 9.47 thousand liters. n DOM2 made a 22% contribution to the Przewalski horses ancestor line. In post-Borley4 there was a 2.3% contribution to the DOM2 line and the more recent 6.8% introgression of DOM2 in Przewalski’s horses [10] .

Opening History

In 1878, Nikolai Mikhailovich Przhevalsky was returning from the second expedition to Central Asia. On the Russian-Chinese border, at the Zaisan checkpoint, he received as a gift from the merchant A.K. Tikhonov the skin and skull of a wild horse obtained by local Kazakh hunters (Kyrgyz-kaisaks). Przhevalsky sent the material to St. Petersburg, to the Zoological Museum, where he was examined by Ivan Polyakov . He discovered that the skin and skull belong to an animal species hitherto unknown to science and made the first description of a wild horse. Polyakov named the species in honor of the discoverer - Przewalski’s horse Equus przewalskii Polj., 1881 [11] .

In captivity

There are about two thousand purebred Przhevalsky horses in the world, which are descended from 11 horses captured at the beginning of the 20th century in Dzungaria and 1 domestic horse. The descendants of those horses have been bred in captivity for many generations in zoos and nature reserves in the world. The Przewalski’s horse book is kept at the Prague Zoo . In the USSR, a large number of Przhevalsky horses was kept in the Askania-Nova Reserve (Ukraine). Before the revolution, it was precisely the founder and owner of Askania-Nova F.E. Falz-Fein who was the first organizer of expeditions to catch Przhevalsky's horses in Dzungaria.

The extremely limited initial gene pool of modern Przhevalsky horses creates serious problems in their breeding: the inevitable constant inbreeding (closely related crosses) inevitably affects the viability of horses and the ability to breed. Not in the best way horses are kept in captivity: in nature, wild horses were in constant motion, walking many kilometers during the day.

In nature, semi-reserves and reserves

The last time in the wild these animals were seen in 1969 in Mongolia. According to eyewitnesses, the number of horses began to decline sharply in the winter of 1944-1945, which was characterized by very severe frosts (below −40 ° C) and daily raging snowstorms. Such winters are quite rare in Mongolia, about once every hundred years. At that time, many livestock died from a non-feed, which forced local residents to hunt wild animals, including Przewalski’s horses. The situation was aggravated by the fact that Chinese and Mongolian troops were introduced into the territory where the horses lived. Armed self-defense units appeared in border areas. All this led to the fact that a huge amount of firearms was concentrated in this territory, the owners of which also did not disdain hunting. As a result, Przhevalsky’s horse disappeared from its natural habitat.

Since 1992, Przewalski’s horses reintroduction (return to the wild) programs have been launched in Mongolia ( Hustain-Nuruu National Park and Tahin-Tal Center, Big Gobi Biosphere Reserve, Section B). Since 2005, a third reintroduction center, Homin Tal, has appeared in Mongolia (located in the buffer zone of Har Us National Park, western Mongolia). These three wild-living populations numbered about four hundred individuals at the end of 2015 [12] . There are also two reintroduction projects in China, a project in Kazakhstan.

Since 2015, the twelfth in the world and the first in Russia project of reintroduction of the Przhevalsky horse has been implemented in Russia in the Orenburg Reserve . Its official name is “The Przhevalsky Horse Semi-Free Population Program in the Orenburgsky Nature Reserve”. In record time, from July to October 2015, all the necessary infrastructure for the first transport was created on the Pre-Ural Steppe section of the Orenburg Reserve and the Przewalski Horse Reintroduction Center was created [13] . And on October 18, 2015, the first group of purebred horses was imported from France [14] . On November 20, two more groups were brought in from the Khortobad National Park, Hungary. In June 2018, the first foal of Przewalski's horse was born at the Reintroduction Center.

In the early 1990s, several horses were released as an experiment into the Ukrainian exclusion zone of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, where they began to breed actively [15] . Now there are about a hundred individuals, 3 herds.

Previously, these wild horses were widespread in the forest-steppes, steppes and semi-deserts of Europe, the steppes and partly the forest-steppes of Kazakhstan and the south of Western Siberia to the east to the Baraba and Pre-Altai steppes, the Salair ridge and Lake Zaysan .

Despite continuous interspecific inbreeding with domestic, wild, and feral common horses, for about 45,000 years of the existence of two separate species, the horse genes did not accumulate horse genes in large numbers, since Przewalski’s horses in nature feed on saxaul and other hard food not suitable for feeding horses . Therefore, hybrids usually went to horses, those left with Przhevalsky's horses usually did not give offspring due to poor nutrition or died. Although the genes of Przhevalsky’s horses entered the genome of ordinary horses, the metabolism, muscle contraction, and heart diseases of Przhevalsky’s horses are controlled by completely different genes - this was shown by DNA studies not only of modern Przhevalsky’s horses, but also of the remains of wild horses that died in the past. [16] According to a study by Russian and Austrian scientists published at the end of the summer of 2017, it turned out that modern Przewalski’s horses in the Dzhungarsky Gobi diet on grassy plants all year round, whereas earlier, in the 19th century, Przewalski’s horses preferred grass in spring in autumn and winter, plucked leaves from bushes of saxaul, caragana, etc. (although they also ate grass). Probably, in the old days, horses changed their diet out of habit, because that’s how they were kulans, and they ate in the steppes. After all, they came to the desert of the Dzungar Gobi from the steppe regions. In addition, earlier horses often had to hide from humans, and in winter they hid in thickets of shrubs scattered across the steppes along the Gobi. Now horses are threatened not by people from whom it was necessary to hide in the bushes, but by wolves and wild dogs. As a result, in winter, Przewalski’s reintroduced horses compete with livestock and domestic horses (herds of which are several times more numerous due to their selection by humans on the basis of complaisance and win because of their large numbers) for the few stocks of green grass in winter, and this limits the breeding of horses Przhevalsky. It became clear that in order to successfully reintroduce and protect their genome from borrowing the genes of ordinary horses, one needs to train Przewalski’s horses to eat leaves of trees and shrubs of steppes and desert before reintroduction. [17]

Description

Przhevalsky’s horse has a strong dense constitution with well-developed skeleton and muscles, a compact physique, dense skin, and a small overgrowth of mane, tail and brushes. The head is large, the ears are small, pointed, mobile, the eyes are small. The neck is straight and thick. The withers are weakly expressed, the back is short, straight, the croup is usually oval in shape, well muscled, the chest is quite wide and deep. The hooves are strong, of the correct form, the limbs have a normal setting. The horn wall of the hooves is shiny, even, the arrow is well developed, full, the horn of the sole is elastic, smooth, without indentations. Sexual dimorphism in the exterior is not expressed. The main measurements (in cm): height at the withers - 136 (from 124 to 153 cm); oblique body length - 138; chest circumference - 158; chest depth - 62; metacarpal circumference - 17. The body format of Przewalski’s horses, grown in natural conditions, is close to a square. Small values of the bony index, as well as related indices of chest depth and mobility (calculated as the ratio of the length of the body to the height of the chest above the ground) indicate undoubted signs of a riding type in Przhevalsky's horse. Thus, in spite of the small caliber, the wild horse in general physique differs markedly from squat, elongated and wide-bodied horses of local breeds. It is close to cultivated horse and trotting breeds. However, a large head on a thick neck is a hallmark of wild horses - the index of large-headedness is the highest in comparison with any breed of domestic horses [18] .

The suit is always Savrasai - sandy yellow with dark limbs, mane and tail. A dark belt along the back from the withers to the tail. The mane is short, erect, without bangs, dark with reddish hair of the color of the main suit at the base. On the legs of some individuals there are stripes - zebroidity. The tip of the muzzle is usually white (the so-called “flour nose”), but in rare horses it is dark yellow (“mole nose”). The upper part of the tail is covered with short hair of the color of the main suit of the horse, at the end - long dark hair. A special mane and tail are the hallmarks of a wild horse. Domestic horses have a long mane and a fluffy tail from the very beginning.

Lifestyle

| The Red Book of Russia the species probably disappeared | |

Przewalski's horses are social animals. They live in small family groups (schools) of several mares and foals (no more than 10-15); led by a mowing stallion [19] . The group is led by the most experienced adult mare. The kosyachny stallion is in the rearguard and makes sure that no one is behind, and the predators cannot attack the young people walking right in front of him. His power in holding the group together is absolute. [20]

Mares reach adulthood at 3 years old, stallions at 2. When young stallions enter adulthood, the mowing stallion expels them from the family. Young stallions, together with old stallions expelled from the stocks, form separate “bachelor groups” [19] . Horses graze most of the day, but prefer evening twilight or morning. In the afternoon, they rest, trying to choose a place on a hill for a better overview of the surroundings, since representatives of this species are distinguished by good eyesight, smell and hearing.

Gallery

Przhevalsky's horse in the Moscow zoo

Przhevalsky's horse in the Moscow zoo

Przhevalsky's horse in the Moscow zoo

Przhevalsky's horse in the Moscow zoo

Przewalski's horses at the Berlin Zoo

In the Hustain-Nuruu National Park, in Mongolia

Przhevalsky horse in the Orenburg reserve

See also

- wild Horse

- Tarpan

- Camargue (horse)

Notes

- ↑ Fisher D., Simon N., Vincent D. The Red Book. Wildlife in danger / lane. from English, ed. A. G. Bannikova . - M .: Progress, 1976. - S. 134-136. - 478 p.

- ↑ "Fundamentals of Genetics and Livestock Breeding" Auth. F. G. Topalov (inaccessible link)

- ↑ Gaddy, LL Biodiversity: Przewalski's Horse, Edna's Trillium, the Giant Squid, and Over 1.5 Million Other Species . - 2005. - P. 6. - ISBN 9780761830894 .

- ↑ Przewalski’s horse // Voronezh State Agrarian University

- ↑ Przewalski Horse Mega-Encyclopedia about animals

- ↑ Charleen Gaunitz et al. Ancient genomes revisit the ancestry of domestic and Przewalski's horses , 2018

- ↑ Przewalski’s horses lost the title of ancestor of all horses of the world

- ↑ In the Orenburg nature reserve told about the origin of the Przhevalsky horses

- ↑ The “wild” story of Przewalski’s horse. The new hypothesis about the secondary wildness of the “Przhevalsy” was not confirmed , October 24, 2018

- ↑ Antoine Fages et al. Tracking Five Millennia of Horse Management with Extensive Ancient Genome Time Series , May 02, 2019

- ↑ Przewalski's horse: the history and biology of an endangered species / LE Boyd & KA Houpt (Eds) .. - Albany: State Univ. of New York Press, 1994 .-- 313 p.

- ↑ King, SRB, Boyd, L., Zimmerman, W. & Kendall, BE 2015. Equus ferus ssp. przewalskii . The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015

- ↑ Bakirova R. T., Zharkikh T. L., 2015. The first stage of the reintroduction of the Przhevalsky horse in the Orenburg reserve. I. Construction of infrastructure // Steppe Bulletin, Fall-Winter, No. 45. P.62-64

- ↑ Svetlana Mironenko Przhevalsky’s horse returns to the steppe // Science and Life . - 2016. - No. 7. - S. 138-143. - URL: http://www.nkj.ru/archive/articles/29088/

- ↑ WILL THE CHERNOBYL ZONE ASKANIYa-NOVA BECOME? - Mirror of the Week

- ↑ Orlando L. et. al. Evolutionary Genomics and Conservation of the Endangered Przewalski's Horse. Current biology. Volume 25, Issue 19, p2577-2583, 5 October 2015

- ↑ K. Stasevich. What did Przewalski’s horses eat a hundred years ago. // Science and life . 09/17/2017

- ↑ Zharkikh T.L., Yasinetskaya N.I. The exterior of the Przewalski horse // Science.-Tech. bull. Ін-та тваринництва UAAN. - 2005. - T. Vipusk No. 89 . - S. 48-52. .

- ↑ 1 2 Paige Williams Wonderful Return of the Przewalski Horse // Smithsonian.com

- ↑ About the Przhevalsky horse. // Russian Geographical Society

Literature

- Klimov V.V. Przhevalsky's Horse / Ed. T.A. Rudenko. - M .: Agropromizdat , 1990. - 256, [32] p. - 107,000 copies. - ISBN 5-10-001028-2 . (region)

- A quantitative assessment of the nutrition of the semi-free group of the Przewalski horse ( Equus przewalskii ) in the steppe habitat (Askania-Nova Reserve) / MK Pozdnyakova [et al.] // Zoological Journal . - 2011. - T. 90, N 3. - S. 368-376.

- Zharkikh TL, Yasynetska NI , 2009. Ten years of development of the Przewalski horse population in the Chernobyl Exciting Zone // Equus. P.139-156.