“ Cayo Duilio ” ( Italian: Caio Duilio ) - Italian battleship type “Andrea Doria” during the First and Second World Wars. It is named after Guy Douilius , the Roman naval commander who won the first naval victory in the history of the Roman fleet in the First Punic War.

| Cayo Duilio | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caio duilio | ||||||

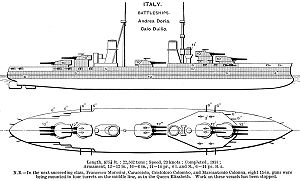

Scheme of battleships of the type "Andrea Doria" | ||||||

| Service | ||||||

| Title | Cayo Duilio | |||||

| original name | Caio duilio | |||||

| Class and type of vessel | battleship type "Andrea Doria" | |||||

| Port of registry | Taranto | |||||

| Organization | Naval Forces and Naval Forces of Italy | |||||

| Manufacturer | Castellammare di Stabia | |||||

| Construction started | February 24, 1912 | |||||

| Launched | April 24, 1913 | |||||

| Commissioned | May 10, 1915 | |||||

| Withdrawn from the fleet | September 15, 1956 | |||||

| Status | cut into metal in 1957 | |||||

| Main characteristics | ||||||

| Displacement | Before modernization : 24729 t After : 28882 t | |||||

| Length | Before modernization : 176 m After : 186.9 m | |||||

| Width | 28 m | |||||

| Draft | 9.4 m | |||||

| Reservation | Gun turrets: 280 mm Main belt: 254 mm Upper deck: 98 mm Chopping: 280 mm | |||||

| Engines | Before modernization : 4 x Parsons steam turbines, 20 boilers After : 4 x Parsons steam turbines, 8 boilers | |||||

| Power | Before modernization : 30,000 liters. with. After : 75,000 liters with. | |||||

| Speed | Before upgrade : 21 knots After : 26 knots | |||||

| Sailing range | 4800 nautical miles at 10 knots | |||||

| Crew | Before modernization : 1233 people (35 officers and 1198 sailors) After : 1485 people (35 officers and 1450 sailors) | |||||

| Armament | ||||||

| Artillery | Before modernization :

After :

| |||||

| Flak | Before modernization : After :

Mine torpedo armament | 3 x 450 mm torpedo tubes | | |||

Content

Features

Standard

The battleship was 176 m long, 28 m wide, and draft 9.4 m. The maximum displacement of the ship ranged from 24715 to 24729 tons. The crew consisted of 1233 people: 35 officers and 1198 sailors. The main power plant consisted of four Parsons steam turbines supported by twenty boilers (twelve coal and eight fuel oil). The boilers were located in two compartments. The total power was 30 thousand hp, the ship developed a speed of 21 knots. Cruising range was 4800 nautical miles at a speed of 10 knots [1] .

The main caliber artillery was made up of thirteen 305-mm 46-caliber guns in five gun turrets: three built and two twin units. The universal artillery had sixteen 152-mm 45-caliber guns located next to the main-caliber gun turrets and in the casemates. Among other things, at the disposal of the ship were thirteen 76-mm guns of 50 caliber and six 76-mm anti-aircraft guns. As a standard capital ship, the battleship Cayo Duilio was equipped with three 450 mm torpedo tubes. Armor for the ship was made at USSteel factories using Krupp technology: the thickness of the armor on the belt was 254 mm, on the main deck 98 mm, on the cockpit and gun turrets 280 mm each [1] .

Modifications

The battleship was rebuilt and repaired in 1937-1940 in Genoa: the tank was expanded up to the main mast. Fodders were rebuilt, thanks to which the ship's length increased to 186.9 m, and displacement to 28882 tons. 12 boilers were removed, and repair of turbines increased the capacity to 75 thousand hp. and speed up to 26 knots. Weapons were also updated: the main caliber was 10 guns of the caliber 320 mm, and the universal guns included 12 built 135 mm cannons (four gun turrets). The anti-aircraft weaponry was completely changed: ten 90-mm, fifteen 37-mm and sixteen 20-mm guns (later four 37-mm guns were added and two 20-mm guns were removed). In total, the crew began to be 1,485 people (35 officers and 1,450 sailors) [2] [3] .

Service

From World War I

The battleship Cayo Duilio was laid in the docks of Castellammare di Stabia on February 24, 1912 , launched on April 24, 1913 , and completed on May 10, 1916 [1] . Almost did not participate in the First World War, just as the battleships of the adversary of Italy, Austria-Hungary did not participate in the war; four times went on patrol, spending about 70 hours at sea. The battleship was based in Taranto from November 1918 to April 1919, but temporarily from November 10, 1918 to January 26, 1919 it was located near the island of Corfu [4] . April 26, 1919 “Cayo Duilio” was sent to Izmir , almost enters the battle with the cruiser “Georgios Averof” on the way , but later the order was canceled: the Greeks occupied Izmir . On June 9, the battleship Roma came to Cayo Duilio, with whom the battleship followed to Constantinople [5] .

“Cayo Duilio” was later sent to the Black Sea to help the White movement in Russia , being there from June 23 to July 13 . During this time, the battleship was transferred to the Lebanese squadron of the Italian Marines Naval Forces. Having completed his mission, the battleship returned to Izmir , from where it sailed on September 9 (it was replaced by the battleship Giulio Cesare ). September 12, “Cayo Duilio” returned to Taranto , having gone to the reserve. In 1920, he returned to the fleet, arriving on June 30 to the shores of Albania and starting shelling its territory ( September 5 left the territorial waters of Albania). The following year, the battleship was enrolled in the Dodecanese squadron, which included patrolling the Eastern Mediterranean. From July 27 to September 10, 1921 he was in Constantinople as part of the Allied squadron [6] .

Interwar years

During the conflict with the Greeks in Corfu, the entire Italian fleet blocked the island, using the assassination of Enrico Tellini and four of his comrades as an excuse for invading Corfu (Cayo Duilio also participated in the blockade). In the same year, Cayo Duilio accompanied Dante Alighieri on his way to Spain. On April 8, 1925, an explosion occurred on board the battleship (ammunition exploded), which damaged the third main-gun gun turret. The ship was sent for repair to La Spezia, from where it returned in April 1928 . From March 18 to June 15, 1930 the battleship was restored in Taranto, on August 11, 1932 it was sent to the reserve, from where it returned a year later. May 19, 1937 "Cayo Duilio" went to Genoa, where he began a three-year repair. On July 15, 1940 , he returned to the fleet in the 5th division of the 1st squadron from Taranto [6] .

In World War II

On August 31, 1940 , the first exit of Cayo Duilio took place during World War II: a battleship with a part of the fleet sailed to intercept the Valiant superdreadnought, which was heading to Alexandria , and the convoy to Malta. The Italians did not have air cover and aerial reconnaissance, which ultimately led to their discovery by the British. September 1, they went to Taranto , but on September 7, “Cayo Duilio” again went on a combat mission to intercept the forces of the “H” formation, which also ended unsuccessfully: the connection went to Dakar . “Cayo Duilio” returned to Taranto, where he remained until November [6] .

Taranto Air

On the night of November 10-11, 1940, the British Mediterranean fleet launched an air-supported attack on Taranto: 21 Fairy Swordfish type bomber flew from the Illastrius aircraft carrier and attacked the Italian fleet in two waves in the harbor. One torpedo hit the Cayo Duilio, three hit the Littorio and another one at the Conte di Cavour [7] . “Cayo Duilio” got hit on the starboard side, a hole 11 × 7 m in size was formed there, which led to the flooding of two compartments with ammunition of the main caliber. We managed to pump water on time, which avoided a roll on board and flooding in the harbor. In January 1941, Cayo Duilio was sent for repairs to Genoa, which began on January 26 [6] .

But even after this successful attack, the British did not waste time and continued to pursue the Italian fleet: the “H” formation under the command of Admiral James Somerville went to Genoa. Ships fired at the port, and everything else, planes from the Ark Royal aircraft carrier dropped magnetic mines into the harbor. Five ships were sunk, but the Cayo Duilio escaped hits [8] . During the battle, the battleship fired about 8 thousand bullets on British aircraft. On May 16, 1941, the battleship left Taranto, entering the 1st squadron [6] .

At the end of the war

The Cayo Duilio, the flagship of the Italian fleet, set off on November 29, 1941 to cover the Italian convoy to North Africa under the guise of the cruiser Giuseppe Garibaldi and six destroyers. On December 13, the battleship set off to escort the M41 convoy, but was soon forced to leave the convoy and rush to the aid of Vittorio Veneto , which was torpedoed. He returned to the port of Cayo Duilio on December 14, leaving two days later to cover the M42 convoy south of Messina with the support of three cruisers and four destroyers. During the escort, the Italians entered the first battle in the Gulf of Sirte , but the Cayo Duilio was too far from the British. The battleship returned to Taranto on December 19 . From January 3 to 6, 1942, the battleship successfully escorted convoy M43 to Tripoli , from January 22 to February 5, it covered convoy T18, in which four of the five transports reached Tripoli [6] .

In February, Cayo Duilio set out to intercept British convoys in the Mediterranean. On February 14, the ship, with the support of a pair of light cruisers and seven destroyers, left the port, but soon returned, as the British lost sight of. On February 21, he escorted a K7 convoy from Messina and Corfu to Taranto. Already at this point, the fleet began to run out of fuel, which led to a limitation of the number of operations and their scope. In the end, “Cayo Duilio” went to the reserve. September 9, 1943 , after the surrender of Italy, he arrived in Malta, where the entire Italian fleet was interned [6] .

In June 1944, the Allies allowed Cayo Duilio to return to Italy: he was in Taranto, Syracuse and Augusta.

On May 1, 1947, the battleship became the flagship of the Italian Navy, and on November 10, 1949, resigned. In 1953, the Cayo Duilio arrived in La Spezia, where he stood until the end of the service. September 15, 1956 he was removed from the lists of the fleet, sold and cut into metal a year later [9] .

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 3 Gardiner & Gray, p. 260

- ↑ Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 284

- ↑ Fraccaroli, p. sixteen

- ↑ Whitley, p. 165

- ↑ Whitley, pp. 165-166

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Whitley, p. 166

- ↑ Rohwer, p. 47

- ↑ Ireland, p. 64

- ↑ Whitley, p. 167

Literature

- Fraccaroli, Aldo. Italian Warships of World War I. - London: Ian Allan, 1970 .-- ISBN 978-0-7110-0105-3 .

- Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. - Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1980. - ISBN 0-87021-913-8 .

- Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1922. - Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1984. - ISBN 0-87021-907-3 .

- Halpern, Paul G. A Naval History of World War I. - Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1995 .-- ISBN 1-55750-352-4 .

- Ireland, Bernard. War in the Mediterranean 1940-1943. - Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2004. - ISBN 1-84415-047-X .

- Rohwer, Jürgen. Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. - Third Revised. - Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2005. - ISBN 1-59114-119-2 .

- Whitley, MJ Battleships of World War II. - Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998 .-- ISBN 1-55750-184-X .

- Woodman, Richard. Malta Convoys 1940-1943. - London: John Murray , 2000 .-- ISBN 0-7195-6408-5 .