The history of trigonometry as a science of the relationship between the angles and sides of a triangle and other geometric figures covers more than two millennia. Most of these relations cannot be expressed with the help of ordinary algebraic operations , and therefore it was necessary to introduce special trigonometric functions that were originally formed in the form of numerical tables.

Historians believe that ancient astronomers created trigonometry ; a little later it began to be used in geodesy and architecture . Over time, the scope of trigonometry has constantly expanded, and today it includes almost all the natural sciences, technology and a number of other areas of activity [1] . Especially useful trigonometric functions were in the study of oscillatory processes ; harmonic function analysis and other analysis tools are also based on them. Thomas Payne in his book The Age of Reason (1794) called trigonometry "the soul of science" [2] .

Content

- 1 Early period

- 2 Ancient Greece

- 2.1 Flat trigonometry

- 2.2 Spherical trigonometry

- 3 Middle Ages

- 3.1 India

- 3.2 Islamic countries

- 3.3 Europe

- 4 New time

- 4.1 XVI — XVII centuries

- 4.2 XVIII century

- 4.2.1 Leonard Euler Reforms

- 4.2.2 Trigonometry in Russia

- 4.3 XIX — XXI centuries

- 5 Historians of trigonometry

- 6 See also

- 7 Notes

- 8 Literature

- 9 References

Early Period

The rudiments of trigonometry can be found in the mathematical manuscripts of ancient Egypt , Babylon and ancient China . The 56th task from the papyrus Rinda (II millennium BC. E.) suggests finding the slope of the pyramid, whose height is 250 cubits, and the length of the side of the base is 360 cubits [3] .

From Babylonian mathematics, the usual measurement of angles in degrees, minutes, and seconds begins (the introduction of these units in ancient Greek mathematics is usually attributed to Gipsicle , II century BC). Among the theorems known to the Babylonians was, for example, the following: an inscribed angle based on the diameter of a circle — a straight line [4] . The main achievement of this period was the correlation, which later received the name of the Pythagorean theorem ; Van der Waerden believes that the Babylonians discovered it between 2000 and 1786 BC. e. [5] It is possible that the Chinese discovered it independently (see " Mathematics in Nine Books "); it is unclear whether the ancient Egyptians knew the general statement of the theorem, but the rectangular “ Egyptian triangle ” with sides 3, 4, and 5 was well known and widely used there [6] [7] .

Ancient Greece

A general and logically connected presentation of trigonometric relations appeared in ancient Greek geometry [8] . Greek mathematicians have not yet identified trigonometry as a separate science - for them it was part of astronomy [9] .

Flat trigonometry

Several trigonometric theorems contain the "Beginnings" of Euclid (IV century BC). In the first book, “The Beginning,” Theorems 18 and 19 establish that the larger side of the triangle corresponds to a larger opposite angle — and vice versa, the larger side corresponds to the larger side. Theorems 20 and 22 formulate the " triangle inequality ": a triangle can be composed of three segments if and only if the length of each is less than the sum of the lengths of the other two. Theorem 32 proves that the sum of the angles of a triangle is 180 °.

In the second book, “The Beginning,” Theorem 12 is a verbal analogue of the cosine theorem [10] :

In obtuse triangles, the square on the side pulling together the obtuse angle is larger than the [sum] of the squares on the sides containing the obtuse angle by a double rectangle enclosed between one of the sides at an obtuse angle, on which the perpendicular falls, and a segment cut off by this perpendicular from the outside at obtuse the corner.

The next theorem 13 is a variant of the cosine theorem for acute-angled triangles. The Greeks did not have an analogue of the sinus theorem ; this most important discovery was made much later [11] .

Further development of trigonometry is associated with the name of the astronomer Aristarchus of Samos (III century BC. E.). In his treatise "On the magnitudes and distances of the Sun and the Moon," the task was set of determining the distances to celestial bodies; this task required the calculation of the aspect ratio of a right triangle with a known value of one of the angles. Aristarchus examined a right-angled triangle formed by the Sun, Moon, and Earth during quadrature . He needed to calculate the magnitude of the hypotenuse (distance from the Earth to the Sun) through the leg (distance from the Earth to the Moon) with a known value of the adjacent angle (87 °), which is equivalent to calculating the value . According to Aristarchus, this value lies in the range from 1/20 to 1/18, that is, the distance to the Sun is 20 times greater than to the Moon [12] ; in fact, the Sun is almost 400 times farther than the Moon, an error arose due to inaccuracies in measuring the angle. Along the way, Aristarchus proved the inequality, which in modern terms is expressed by the formula:

The same inequality is contained in the "Calculus of grains of sand" by Archimedes [13] . In the writings of Archimedes (III century BC) there is an important theorem of division of chords, essentially equivalent to the formula for the sine of a half angle [14] [15] :

Throughout the entire period of the development of ancient science, astronomy remained the main field for applying the results of plane trigonometry to the Greeks. In addition to the task of calculating distances, trigonometry was required to determine the parameters of the system of epicycles and / or eccentrics representing the motion of the star in space. According to the widespread belief, this problem was first formulated and solved by Hipparchus (mid II century BC) in determining the elements of the orbits of the Sun and Moon; perhaps astronomers of an earlier time were engaged in similar tasks. He is often credited with authorship of the first trigonometric tables that have not reached us [16] . However, according to some reconstructions, the first trigonometric tables were compiled in the III century BC. e., possibly Apollonius of Perga [17] .

Instead of the modern sinus function, Hipparchus and other ancient Greek mathematicians usually considered the dependence of the length of the chord of a circle on a given central angle (or, equivalently, on a given arc of a circle, expressed in angular measure). In modern terminology, the length of the chord contracting the arc θ of the unit circle is equal to the doubled sine of the central angle θ / 2. This correspondence is valid for any angles: 0 ° <θ <360 °. In the language of chords, the first trigonometric relations discovered by the Greeks were formulated [1] . For example, the modern formula:

the Greek theorem corresponded [18] :

Where - chord for the central angle , Is the diameter of the circle.

Moreover, the radius of the circle was not considered equal to unity, as it is now. For example, in Hipparchus, the radius of the circle was supposedly considered equal to R = 3438 units - with this definition, the length of the circular arc was equal to the angular measure of this arc, expressed in minutes: , and it made calculations easier. Ptolemy has R = 60 units. According to modern reconstructions [16] [19] , the values of chords near Hipparchus were tabulated with an interval of 7 ° 30 '. Perhaps the calculation of the Hipparchus table was based on a method developed by Archimedes and dating back to Aristarchus [20] .

( Ptolemy's theorem )

Later, the second-century astronomer Claudius Ptolemy at Almagest supplemented the results of Hipparchus. Thirteen books of the Almagest is the most significant trigonometric work of all antiquity. In particular, Almagest contains extensive five-digit chord tables for sharp and obtuse angles, in increments of 30 arc minutes [1] . To calculate the chords, Ptolemy used (in chapter X) the Ptolemy theorem (known, however, by Archimedes), which states: the sum of the products of the lengths of the opposite sides of a convex quadrilateral inscribed in a circle is equal to the product of the lengths of its diagonals. It is not difficult to deduce from this theorem two formulas for the sine and cosine of the sum of the angles and two more for the sine and cosine of the difference in angles, but the Greeks do not have a general formulation of these theorems [21] .

The main achievement of the ancient trigonometric theory was the general solution of the problem of “solving triangles” , that is, finding unknown elements of a triangle based on its three given elements (of which at least one is a side) [8] . Subsequently, this problem and its generalizations became the main task of trigonometry [1] : several (usually three) known elements of a triangle are specified, and the remaining quantities associated with it are required to be found. Initially, the triangle elements (known or unknown) included the sides and angles at the vertices, later medians , heights , bisectors , the radius of the inscribed or described circle, the position of the center of gravity , etc. were added to them. Applied trigonometric problems are very diverse - for example, measurable in practice the results of actions on the listed values (for example, the sum of the angles or the ratio of the lengths of the sides) can be set.

Spherical trigonometry

In parallel with the development of trigonometry, the Greeks, under the influence of astronomy, far advanced spherical trigonometry . Euclid’s “Beginnings” on this subject contains only a theorem on the ratio of the volumes of balls of different diameters, but the needs of astronomy and cartography caused the rapid development of spherical trigonometry and related areas - the system of celestial coordinates , the theory of cartographic projections , and the technology of astronomical instruments (in particular, invented astrolabe [22] ).

Historians have not reached a consensus about the degree of development of the geometry of the celestial sphere among the ancient Greeks. Some researchers argue that the ecliptic or equatorial coordinate system was used to record the results of astronomical observations at least already in the time of Hipparchus [23] . Perhaps then some theorems of spherical trigonometry were known, which could be used to compile star catalogs [24] and in geodesy .

The first works known to us on Spherics (that is, spherical geometry, with a clear astronomical bias) wrote [25] :

- (IV century BC. E.) Autolycus from Pitana and Euclid ("Phenomena").

- (II century BC. E.) Theodosius and Gipsicle .

Some of the problems analyzed in these essays are trigonometric in nature, however, due to the poor development of the theory, the authors still use workarounds. For example, the task "to find the time of full rise (set) of the zodiacal constellation " Gipsicle solves approximately using polygonal numbers [25] .

The decisive step in the development of the theory was the monograph “Sphere” in three books, which was written by Menelaus of Alexandria (about 100 CE). In the first book, he outlined theorems on spherical triangles , similar to Euclidean theorems on flat triangles (see Book I, “The Beginning”). Historians believe that Menelaus's approach is largely based on the writings of Theodosius , which Menelaus significantly expanded and brought into the system. According to Papp , Menelaus was the first to introduce the concept of a spherical triangle as a figure formed by segments of large circles [26] . Menelaus proved a theorem for which Euclid has no flat analogue: two spherical triangles are congruent (compatible) if the corresponding angles are equal. His other theorem states that the sum of the angles of a spherical triangle is always greater than 180 ° [26] .

The second book, Spherics, outlines the application of spherical geometry to astronomy. The third book contains Menelaus' theorem , important for practical astronomy, known as the “rule of six quantities” [27] . Two other fundamental theorems discovered by Menelaus were subsequently called the “rule of four quantities” and the “rule of tangents” [26] .

Several decades later, Claudius Ptolemy in his works "Geography", "Analemma" and "Planisphere" gives a detailed exposition of trigonometric applications to cartography, astronomy and mechanics. Among other things, a stereographic projection is described, several practical problems are investigated, for example: to determine the altitude and azimuth of a celestial body by its declination and time angle . From the point of view of trigonometry, this means that you need to find the side of the spherical triangle on the other two sides and the opposite corner [28] .

Spherical geometry Ptolemy also dedicated the XIII chapter in the first book of the Almagest; unlike Menelaus, Ptolemy did not give evidence of many statements, but he paid much attention to algorithms suitable for practical calculations in astronomy. The supporting structure, instead of flat chords, in the Almagest is the “four-sided Menelaus”. To “solve” a right-angled spherical triangle, that is, to calculate its characteristics, Ptolemy cited 4 theorems in a verbal record; in modern notation they have the form (angle direct) [29] :

- (special case of the spherical sine theorem )

- (special case of the spherical cosine theorem )

Let us explain that in spherical geometry it is customary to measure the sides of a triangle not by linear units, but by the magnitude of the central angles resting on them. In modern spherical trigonometry, two more relations are given:

- (also follows from the spherical cosine theorem)

Ptolemy does not have them, since they cannot be deduced from Menelaus' theorem [29] .

Middle Ages

India

In the IV century, after the decline of ancient science, the center for the development of mathematics moved to India. The works of Indian mathematicians ( siddhanta ) show that their authors were well acquainted with the works of Greek astronomers and geometers [30] . Indians were not very interested in pure geometry, but their contribution to applied astronomy and the calculated aspects of trigonometry is very significant.

First of all, Indians changed some concepts of trigonometry, bringing them closer to modern ones. They replaced the ancient chords with sines (the name "sinus" goes back to the word "bowstring" in Sanskrit [31] ) in a right triangle .Thus, trigonometry was laid in India as a general doctrine of relations in a triangle, although, unlike the Greek chords, the Indian approach was limited only to the functions of an acute angle [32] .

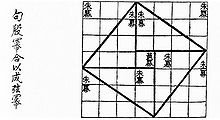

Синус индийцы определяли несколько иначе, чем в современной математике (см. рис. справа): под синусом понималась длина отрезка AD, опирающегося на дугу AC окружности радиуса R= 3438 единиц (как у Гиппарха ). Таким образом, «индийский синус» угла в 3438 раз больше современного синуса и имел размерность длины [31] . Из этого правила были исключения; например, Брахмагупта по неясным причинам принял радиус равным 3270 единиц [33] .

Индийцы первыми ввели в использование косинус . Использовался ещё так называемый обращённый синус, или синус-верзус , равный длине отрезка DC на рисунке справа [34] .

Как и у греков, тригонометрия индийцев развивалась главным образом в связи с её астрономическими приложениями, в основном для использовании в теории движения планет и для изучения небесной сферы. Это свидетельствует о хорошем знании сферической тригонометрии «Альмагеста» и «Аналеммы», однако ни одной их собственной работы, развивающей теорию этого раздела тригонометрии, не обнаружено [35] . Тем не менее в разработке прикладных алгоритмов решения астрономических задач индийцы достигли больших успехов [30] . Например, в «Панча-сиддхантике» Варахамихиры (VII в.) даётся оригинальное решение астрономической задачи, описанной у Птолемея: найти высоту Солнца над горизонтом, если известны широта местности, склонение Солнца и его часовой угол . Автор для решения применяет аналог теоремы косинусов [36] , он же впервые привёл формулу для синуса половинного угла [37] .

Для астрономических расчётов был составлен ряд тригонометрических таблиц. Первые (четырёхзначные) таблицы синусов приведены в древней «Сурья-сиддханте» и у Ариабхаты («Ариабхатия», V век). Таблицы Ариабхаты содержат 24 значения синусов и синус-верзусов с интервалом 3°45' (половина шага таблиц у Гиппарха).

Важный вклад в развитие тригонометрии внес Брахмагупта (VII в.), открывший интерполяционную формулу , которая позволила ему получить значения синуса на основе небольшого количества известных значений этой функции [38] . Кроме того, индийцы знали формулы для кратных углов , for . В «Сурья-сиддханте» и в трудах Брахмагупты при решении задач фактически используется сферический вариант теоремы синусов , однако общая формулировка этой теоремы в Индии так и не появилась [39] . Историки нашли в индийских трудах неявное использование тангенсов , но важность этого понятия была осознана только позже, математиками исламских стран [30] .

В трудах другого выдающегося ученого, Бхаскары II (XII век), приводятся формулы для синуса и косинуса суммы и разности углов:

а также формула для малого приращения синуса:

(при ), соответствующая современному выражению для дифференциала синуса. Опираясь на формулу синуса суммы, Бхаскара опубликовал более точные и подробные, чем у Ариабхаты, тригонометрические таблицы с шагом 1° [40] .

В XI веке мусульмане ( Махмуд Газневи ) захватили и разорили Северную Индию. Культурные центры переместились в Южную Индию, где образуется так называемая « керальская школа астрономии и математики » (по названию современного штата Керала на юге Индии) [41] . В XV—XVI веках математики Кералы в ходе астрономических исследований добились больших успехов в области суммирования бесконечных числовых рядов, в том числе для тригонометрических функций [39] . В анонимном трактате «Каранападдхати» («Техника вычислений») даны правила разложения синуса и косинуса в бесконечные степенные ряды [42] , восходящие, вероятно, к основателю этой школы астроному Мадхаве из Сангамаграмы (1-я половина XV века) [43] . Мадхава и его последователь Нилаканта (в трактате « Taнтpacaнrpaха ») приводят также правила разложения арктангенса в бесконечный степенной ряд. В Европе к подобным результатам подошли лишь в XVII—XVIII веках. Так, ряды для синуса и косинуса вывел Исаак Ньютон около 1666 года, а ряд арктангенса был найден Дж. Грегори в 1671 году и Г. В. Лейбницем в 1673 году [44] .

Исламские страны

В VIII веке учёные стран Ближнего и Среднего Востока познакомились с трудами древнегреческих и индийских математиков и астрономов. Переводом их на арабский язык занимались такие крупные учёные VIII века, как Ибрахим Ал-Фазари и Якуб ибн Тарик . Далее они и их последователи стали активно комментировать и развивать эти теории. Опорной конструкцией у исламских учёных, как и у индийцев, был синус в треугольнике, или, что то же самое, полухорда в круге [35] .

Их астрономические трактаты, аналогичные индийским сиддхантам, назывались « зиджи »; типичный зидж представлял собой сборник астрономических и тригонометрических таблиц, снабжённый руководством по их использованию и (не всегда) изложением общей теории [45] . Сравнение зиджей периода VIII—XIII веков показывает быструю эволюцию тригонометрических знаний. Предметом особого внимания ученых стран ислама была сферическая тригонометрия, методы которой использовались для решения задач астрономии и геодезии [46] . Среди основных решаемых проблем были следующие [47] [45] .

- — Точное определение времени суток.

- — Вычисление будущего расположения небесных светил, моментов их восхода и заката, затмений Солнца и Луны .

- — Нахождение географических координат текущего места.

- — Вычисление расстояния между городами с известными географическими координатами .

- — Определение направления на Мекку ( кибла ) из заданного места.

- — Вычисление будущего расположения небесных светил, моментов их восхода и заката, затмений Солнца и Луны .

Самые ранние из сохранившихся трудов принадлежат ал-Хорезми и ал-Марвази (IX век), которые рассмотрели, наряду с известными ещё индийцам синусом и косинусом, новые тригонометрические функции: тангенс , котангенс , секанс и косеканс [34] . Изначально эти функции определялись иначе, чем в современной математике. Так, под котангенсом понималась длина тени от вертикального гномона высотой 12 (иногда 7) единиц; первоначально эти понятия использовались для расчёта солнечных часов . Тангенсом называлась тень от горизонтального гномона. Косекансом и секансом назывались гипотенузы соответствующих прямоугольных треугольников (отрезки AO на рисунке справа) [48] . Лишь в X веке философ и математик ал-Фараби в своих комментариях к «Альмагесту» ввёл независимые от гномоники определения этих четырёх функций, определив их через синус и косинус в тригонометрическом круге птолемеевского радиуса (60 единиц). Основные соотношения между всеми шестью функциями привёл ал-Баттани в том же столетии. Окончательной унификации добился Абу-л-Вафа во второй половине X века, который впервые использовал для определения тригонометрических функций круг единичного радиуса, как это делается в современной математике.

Сабит ибн Курра (IX век) и ал-Баттани (X век) первыми открыли фундаментальную теорему синусов для частного случая прямоугольного сферического треугольника . Для произвольного сферического треугольника доказательство было найдено (разными способами и, вероятно, независимо друг от друга) Абу-л-Вафой, ал-Худжанди и ибн Ираком в конце X века [11] . В другом трактате ибн Ирака сформулирована и доказана теорема синусов для плоского треугольника [49] .

Сферическая теорема косинусов в общем виде сформулирована в странах ислама не была, однако в трудах Сабита ибн Курры, ал-Баттани и других астрономов имеются эквивалентные ей утверждения. Вероятно, поэтому Региомонтан , впервые давший общую формулировку этой важного соотношения (XV век), назвал его «теоремой Альбатегния» (так тогда в Европе называли ал-Баттани) [50] .

Ибн Юнис (X век) открыл преобразование произведения тригонометрических функций в сумму [51] , например:

Формулы преобразования позволяли заменить трудоёмкое умножение на более простое сложение или вычитание. Впоследствии в Европе эти же формулы использовали для противоположной цели — замены сложения и вычитания на умножение, чтобы затем для вычисления результата применить логарифмические таблицы [52] .

Одной из важнейших задач науки того времени являлось составление тригонометрических таблиц с как можно меньшим шагом. В IX веке ал-Хорезми составил таблицы синусов с шагом 1°, его современник Хаббаш аль-Хасиб (ал-Марвази) добавил к ним первые таблицы тангенсов, котангенсов и косекансов (с тем же шагом) [34] . В начале X века ал-Баттани опубликовал таблицы с шагом 30', в конце того же столетия Ибн Юнис составил таблицы с шагом 1' [53] . При составлении таблиц ключевым было вычисление значения . Искусные методы для вычисления этой величины изобрели Ибн Юнис, Абу-л-Вафа , ал-Бируни . Наибольшего успеха добился в XV веке ал-Каши ; в одной из своих работ он подсчитал, что (все знаки верны). В составленных при его участии «Астрономических таблицах» Самаркандской обсерватории Улугбека таблицы синусов вычислены с шестью шестидесятеричными знаками [54] , с шагом 1'. Султан Улугбек лично участвовал в этой работе: он написал специальный трактат о вычислении синуса угла в 1°.

Первым специализированным трактатом по тригонометрии было сочинение среднеазиатского учёного ал-Бируни (X—XI век) «Книга ключей науки астрономии» (995—996 годы). Целый курс тригонометрии содержал главный труд ал-Бируни — «Канон Мас'уда» (книга III). В дополнение к таблицам синусов (с шагом 15') Ал-Бируни дал таблицы тангенсов (с шагом 1°). Идеологически труды Бируни близки к птолемеевским — на языке хорд он формулирует теоремы о синусе удвоенного и половинного угла, синусе суммы и разности углов [55] . Среди приложений книга Ал-Бируни показывает построение правильного вписанного девятиугольника и приближённое вычисление длины его стороны; этот алгоритм он использует для нахождения . В другом труде, «Геодезия», Бируни сообщил результаты собственных измерений длины земного меридиана , из которых следует оценка радиуса Земли, близкая к истинной (в пересчёте к метрической системе , Бируни получил 6340 км) [56] .

Фундаментальное изложение тригонометрии как самостоятельной науки (как плоской, так и сферической) дал персидский математик и астроном Насир ад-Дин ат-Туси в 1260 году [57] . Его «Трактат о полном четырёхстороннике» содержит практические способы решения типичных задач, в том числе труднейших, решенных самим ат-Туси — например, построение сторон сферического треугольника по заданным трём углам [58] . Приведена теорема тангенсов для сферических треугольников, описано важное понятие полярного треугольника (впервые использованное в XI веке Ибн Ираком и ал-Джайяни ). Сочинение ат-Туси стало широко известно в Европе и существенно повлияло на развитие тригонометрии.

Таким образом, к концу XIII века были открыты базовые теоремы, составляющие содержание тригонометрии:

- — Выражение любой тригонометрической функции через любую другую.

- — Формулы для синусов и косинусов кратных и половинных углов, а также для суммы и разности углов.

- — Теоремы синусов и косинусов.

- — Решение плоских и сферических треугольников

- — Формулы для синусов и косинусов кратных и половинных углов, а также для суммы и разности углов.

Из-за отсутствия алгебраической символики все перечисленные теоремы выражались в громоздкой словесной форме, но по существу были полностью эквивалентны современному их пониманию.

Европа

После того как арабские трактаты были в XII—XIII веках переведены на латынь, многие идеи индийских и персидских математиков стали достоянием европейской науки. По всей видимости, первое знакомство европейцев с тригонометрией состоялось благодаря зиджу ал-Хорезми , два перевода которого были выполнены в XII веке. Первоначально сведения о тригонометрии (правила её использования, таблицы некоторых тригонометрических функций) приводились в сочинениях по астрономии, однако в сочинении Фибоначчи «Практика геометрии», написанном около 1220 года, тригонометрия излагается как часть геометрии. Первым европейским сочинением, целиком посвященным тригонометрии, часто называют «Четыре трактата о прямых и обращенных хордах» английского астронома Ричарда Уоллингфордского (около 1320 г.). Книга содержит доказательство ряда тригонометрических тождеств и оригинальный метод вычисления синусов. Примерно в те же годы был написан трактат еврейского математика Леви бен Гершома (Герсонида) «О синусах, хордах и дугах», переведённый на латинский язык в 1342 году [59] . Книга содержит доказательство теоремы синусов и пятизначные таблицы синусов [60] . Тригонометрия затрагивается в «Теоретической геометрии» английского математика Томаса Брадвардина (написана в первой половине XIV в., опубликована в 1495 году). Тригонометрические таблицы, чаще переводные с арабского, но иногда и оригинальные, содержатся в сочинениях ряда других авторов XIV—XV веков. Тогда же тригонометрия заняла место среди университетских курсов.

Крупным достижением стала монография Региомонтана «Пять книг о треугольниках всех видов» (опубл. 1462—1464), в которой были сведены все известные к этому моменту знания по плоской и сферической тригонометрии и приложены семизначные таблицы синусов (с шагом 1') и тангенсов (с шагом 1°). Немаловажно и то, что в таблицах Региомонтана, в нарушение астрономической традиции, впервые использовалась десятичная система (а не архаичная шестидесятеричная ). Радиус тригонометрического круга Региомонтан принял равным , чтобы табличные значения были представлены целыми числами (десятичные дроби вошли в обиход несколько позднее, причём мощным стимулом к их применению стали именно тригонометрические вычисления [61] ).

По сравнению с трактатом ат-Туси сочинение Региомонтана существенно полнее, оно содержит ряд новых задач, решённых оригинальными методами. Например, показывается, как построить треугольник, если известны одна его сторона, длина опущенной на неё высоты и противолежащий угол [62] .

Новое время

XVI—XVII века

Развитие тригонометрии в Новое время стало чрезвычайно важным не только для астрономии и астрологии, но и для других приложений, в первую очередь артиллерии , оптики и навигации при дальних морских путешествиях. Поэтому после XVI века этой темой занимались многие выдающиеся учёные, в том числе Николай Коперник , Иоганн Кеплер , Франсуа Виет [63] . Коперник посвятил тригонометрии две главы в своём трактате « О вращении небесных сфер » (1543). Вскоре (1551) появились 15-значные тригонометрические таблицы Ретика , ученика Коперника, с шагом 10" [64] . Кеплер опубликовал труд «Оптическая часть астрономии» (1604).

Потребность в сложных тригонометрических расчётах вызвала в начале XVII века открытие логарифмов , причём первые логарифмические таблицы Джона Непера содержали только логарифмы тригонометрических функций. Среди других открытий Непера — эффективный алгоритм решения сферических треугольников , получивший название « формулы аналогии Непера » [65] .

Термин «тригонометрия» как название математической дисциплины ввёл в употребление немецкий математик Б. Питискус , опубликовавший в 1595 году книгу «Тригонометрия, или краткий и ясный трактат о решении треугольников » ( лат. Trigonometria: sive de solutione triangulorum tractatus brevis et perspicuus ). К концу XVII века появились современные названия тригонометрических функций. Термин «синус» впервые употребил около 1145 года английский математик и арабист Роберт Честерский [31] . Региомонтан в своей книге назвал косинус «синусом дополнения» ( лат. sinus complementi ), поскольку ; его последователи в XVII веке сократили это обозначение до co-sinus (Эдмунд Гунтер) [63] , а позднее — до cos ( Уильям Отред ). Названия тангенса и секанса предложил в 1583 году датский математик Томас Финке [63] , а упомянутый выше Эдмунд Гунтер ввёл названия котангенса и косеканса . Термин «тригонометрические функции» впервые употребил в своей «Аналитической тригонометрии» (1770) Георг Симон Клюгель [66] .

Томас Финке предложил оригинальное решение геодезической задачи: найти углы треугольника, если известна их сумма и отношение противолежащих сторон . Для решения Финке использовал формулу Региомонтана (см. рисунок) [67] :

Виет в первой части своего «Математического канона» (1579) поместил разнообразные таблицы, в том числе тригонометрические, а во второй части дал обстоятельное и систематическое, хотя и без доказательств, изложение плоской и сферической тригонометрии. В 1593 году Виет подготовил расширенное издание этого капитального труда. «Несомненно, что самый интерес его к алгебре первоначально был вызван возможностью приложений к тригонометрии и астрономии» [68] . Другой важной заслугой Виета стало применение в тригонометрии разработанной им общей алгебраической символики; если ранее решение задачи понималось как геометрическое построение, то начиная с работ Виета приоритет начинает переходить к алгебраическим вычислениям [69] . Появление символики позволило записать в компактном и общем виде тригонометрические тождества — например, формулы для кратных углов [70] :

Надо оговориться, что сам Виет ещё дал эти формулы частично в словесном описании, но при этом ясно указал на связь коэффициентов формул с биномиальными коэффициентами и привёл таблицу их значений для небольших значений [68] .

Из других достижений Виета [71] : в работе «Дополнение к геометрии» Виет указал тригонометрический способ решения кубического уравнения для самого трудного в тот период — неприводимого — случая (стандартная формула требует умения работать с корнями из комплексных чисел ). Виет дал первое в истории бесконечное произведение:

Кроме артиллерии и навигации, тригонометрия быстро развивалась и в таких классических областях её применения, как геодезия . Широкое применение тангенсов объяснялось, в частности, простотой измерения с их помощью высоты горы или здания (см. рисунок):

В 1615 году Снеллиус нашёл решение «задачи Снеллиуса-Потенота» : найти точку, из которой стороны данного (плоского) треугольника видны под заданными углами. Он открыл закон преломления света : для заданных исходной и преломляющей среды отношение синусов угла падения и угла преломления постоянно. Тем самым Снеллиус открыл дорогу новым применениям тригонометрических функций в оптике, а изобретение в эти же годы первых телескопов придало этому открытию особую важность.

Первый график синусоиды появился в книге Альбрехта Дюрера «Руководство к измерению циркулем и линейкой» ( нем. Underweysung der Messung mit dem Zirkel und Richtscheyt , 1525 год) [72] . В 1630-х годах Жиль Роберваль , в ходе своих исследований циклоиды , независимо вычертил синусоиду [73] , он же опубликовал формулу тангенса двойного угла [52] . Джон Валлис в своей «Механике» (1670), опередив своё время, правильно указал знаки синуса во всех квадрантах и указал, что у синусоиды бесконечно много «оборотов». График тангенса для первого квадранта впервые начертил Джеймс Грегори (1668) [74] .

Во второй половине XVII века началось стремительное развитие общей теории квадратур (то есть вычисления площади), завершившееся появлением в конце века математического анализа . Для тригонометрических функций важные результаты в начале этого периода получил Блез Паскаль (опубликованы в его книге «Письма А. Деттонвилля о некоторых его геометрических открытиях», 1659 год). В современной терминологии, Паскаль вычислил интегралы от натуральных степеней синуса и косинуса и некоторые связанные с ними [75] , а также отметил, что . Работы в области тригонометрии проводили такие крупные математики XVII века, как Отред , Гюйгенс , Озанам , Валлис . Заметным процессом во второй половине XVII века стала постепенная алгебраизация тригонометрии, совершенствование и упрощение её символики (хотя до Эйлера символика была всё же гораздо более громоздка, чем современная) [76] .

18th century

After the discovery of mathematical analysis, first James Gregory , and then Isaac Newton received the expansion of trigonometric functions (as well as inverse to them ) in infinite series . Newton devoted 10 problems to the problems of geometry and trigonometry in his book “ Universal Arithmetic ” [77] . For example, in Problem X, you need to “solve a triangle” if one side, the opposite angle, and the sum of the other two sides are known. The solution method proposed by Newton is one of the Molweide formulas [78] .

Leibniz rigorously proved that cannot be, generally speaking, algebraically expressed in terms of , that is, in modern terminology, trigonometric functions are transcendental [79] .

Important discoveries at the beginning of the XVIII century were:

- - The discovery and widespread use of the radian measure of angles [80] ( Roger Cotes , 1714). The term “radian” itself appeared later; it was proposed in 1873 by the English engineer James Thomson [81] .

- - Trigonometric representation of a complex number and Moiré formula .

- - The beginning of the use ( Newton and Gregory ) of the polar coordinate system associated with Cartesian trigonometric relations; Euler (1748) [82] introduced these coordinates into general use.

- - Trigonometric representation of a complex number and Moiré formula .

In 1706, the Swiss mathematician Jacob German published formulas for the tangent of the sum and the tangent of multiple angles, and Johann Lambert in 1765 found extremely useful formulas expressing different trigonometric functions in terms of the half-angle tangent [83] . Studying hyperbolic functions (1761), Lambert showed that their properties are similar to those of trigonometric ones; The reason for this was discovered in 1707 by Moiré : when replacing a real argument with an imaginary circle, it goes into a hyperbola , and trigonometric functions into the corresponding hyperbolic ones [84] .

German mathematician Friedrich Wilhelm von Oppel in the book “Analysis of Triangles” (1746) published both formulas of Molveide in a modern record [85] .

In the book "Polygonometry" (1789), Simon Liuilier summarized trigonometric relations for triangles, giving their analogues for arbitrary polygons, including spatial. In his work on this subject, Lugillier presented the main theorem of polygonometry : the area of each face of a polyhedron is the sum of the products of the areas of the remaining faces by the cosines of the angles formed by them with the first face . He examined ways to "solve polygons" with parties for various statements of the problem: given side and corners, or all corners and sides or all sides and angle [86] .

In 1798, Legendre proved that if the dimensions of a spherical triangle are small compared to the radius of the sphere, then when solving trigonometric problems, one can apply the formulas of plane trigonometry, subtracting a third of the spherical excess from each angle [87] .

The way to denote the inverse trigonometric functions using the prefix arc (from Latin arcus - arc) appeared in the Austrian mathematician Karl Scherfer ( Karl Scherffer , 1716-1783) and entrenched thanks to Lagrange . It was meant that, for example, the usual sine allows you to find the chord contracting it along the arc of a circle, and the inverse function solves the opposite problem. English and German schools of mathematics until the end of the 19th century offered other notations: but they did not take root [88] .

Leonard Euler Reforms

Leonard Euler gave the modern form of trigonometry. In the treatise "Introduction to the Analysis of Infinite" (1748), Euler defined the trigonometric functions equivalent to the modern one [77] , and accordingly defined the inverse functions . If his predecessors understood the sine and other concepts geometrically, that is, as lines in a circle or triangle, then after the work of Euler etc. began to be regarded as dimensionless analytical functions of a real and complex variable. For the complex case, he established the connection of trigonometric functions with an exponential function ( Euler's formula ). Euler's approach has since become generally accepted and is included in textbooks.

Euler considered negative angles and angles greater than 360 ° as permissible, which made it possible to determine trigonometric functions on the whole real number line and then continue them on the complex plane . When the question arose of extending trigonometric functions to obtuse angles, the signs of these functions before Euler were often chosen erroneously; many mathematicians considered, for example, the cosine and obtuse tangent positive [73] . Euler determined these signs for angles in different coordinate quadrants based on the reduction formulas [89] .

Euler first introduced the expansion of trigonometric functions into infinite products (1734), whence he derived series for their logarithms [90] .

In other works, first of all, “The Foundations of Spherical Trigonometry Derived from the Method of Maxima and Minima” (1753) and “General Spherical Trigonometry, Briefly and Clearly Derived from the First Foundations” (1779), Euler for the first time gave a complete systematic exposition of spherical trigonometry on analytical based on [91] , and many of the major results belong to Euler himself.

In the middle of the 18th century, the most important in its consequences “debate about the string” [92] . Euler, in a polemic with D'Alembert, proposed a more general definition of function than was previously accepted; in particular, a function can be defined by a trigonometric series . In his writings Euler used several representations of algebraic functions in the form of a series of multiple arguments of trigonometric functions, for example [93] :

Euler did not deal with the general theory of trigonometric series and did not study the convergence of the obtained series, but obtained several important results. In particular, he derived decompositions of integer degrees of sine and cosine [93] .

Trigonometry in Russia

In Russia, the first information on trigonometry was published in the collection “Tables of logarithms, sinuses and tangents for the study of sophisticated carers”, published with the participation of L. F. Magnitsky in 1703 [94] . In 1714, a meaningful manual “Geometry Practice” appeared, the first Russian textbook on trigonometry, focused on the applied tasks of artillery, navigation and geodesy [95] . The completion of the period of mastering trigonometric knowledge in Russia can be considered the fundamental textbook of academician M. E. Golovin (Euler’s student) “Flat and spherical trigonometry with algebraic proofs” (1789).

At the end of the 18th century, an authoritative trigonometric school ( A. I. Lexel , N. I. Fuss , F. I. Schubert ) arose in St. Petersburg, which made a great contribution to plane and spherical trigonometry [66] .

XIX-XXI centuries

At the beginning of the 19th century, N. I. Lobachevsky added a third section to the flat and spherical trigonometry - hyperbolic (for Lobachevsky geometry , the first work in this area was published by F. A. Taurinus in 1826). Lobachevsky showed that the formulas of spherical trigonometry go over to the formulas of hyperbolic trigonometry when replacing the lengths of the sides of the triangle a, b, c by imaginary values: ai, bi, ci - or, equivalently, when replacing trigonometric functions with the corresponding hyperbolic ones [96] .

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the theory of trigonometric series and related areas of mathematics developed rapidly: harmonic analysis , the theory of random processes , coding of audio and video information, and others. Even Daniel Bernoulli expressed the conviction that any (continuous) function at a given interval can be represented by a trigonometric series [97] . Discussions continued until 1807, when Fourier published the theory of the representation of arbitrary piecewise-analytic functions by trigonometric series (the final version is contained in his "Analytical Theory of Heat", 1822) [92] . To decompose a function in a row:

Fourier cited the integral formulas for calculating the coefficients [92] :

Fourier's presentation was not strict in the modern sense, but already contained a study of the convergence of most of the series he received. For functions defined on the whole number line and not periodic, Fourier proposed a decomposition into the Fourier integral .

The versatility and effectiveness of Fourier analysis methods made a great impression on the scientific world. Whereas earlier trigonometric series were used in mathematical physics mainly for studying periodic processes (string oscillations, celestial mechanics , pendulum motion, etc.), then completely different processes (heat transfer) were studied in Fourier work, and trigonometric series helped to obtain valuable practical results . From that moment on, trigonometric series and integrals became a powerful tool for analyzing various functions. The Fourier results were continued and deepened by Poisson and Cauchy ; the question of convergence of series was studied in detail by Dirichlet and other mathematicians [98] . Riemann in his dissertation investigated arbitrary trigonometric series, not necessarily related to the expansion of a function (1853), formulated for them the “principle of localization”. The question of the representability of an arbitrary measurable and finite function almost everywhere by a trigonometric series (which does not necessarily coincide with its Fourier series) was solved in 1941 by Menshov's theorem .

Exploring the sets of singular points for trigonometric series, Georg Kantor developed the theory of sets, fundamental for all mathematics [99] . The theory of trigonometric series had a huge impact on the development of complex analysis , mathematical physics , electronics, and many other branches of science [92] . The theory of functions of a real variable , the theory of measures, and the Lebesgue integral appeared and further developed in close connection with the theory of trigonometric series [92] [100] . Important practical applications are the approximation of functions by finite trigonometric polynomials [101] (also used for interpolation ).

Historians of trigonometry

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, works on the history of mathematics and astronomy paid considerable attention to the history of trigonometry ( J. E. Montucla , J. B. J. Delambre , G. Hankel , P. Tannery and others). In 1900, the German mathematics historian Anton von Braunmühl published the first monograph in two volumes, specially dedicated to the history of trigonometry [102] . In the XX century, major works on this topic were published by I. G. Zeiten , M. B. Kantor , O. Neugebauer , B. A. Rosenfeld , G. P. Matvievskaya and others.

See also

- Astronomy of Ancient Greece

- Astronomy of the Islamic Middle Ages

- History of math

- Trigonometric Identities

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Vygodsky M. Ya. Handbook of Elementary Mathematics. - M .: Nauka, 1978.- S. 266-268.

- ↑ Paine, Thomas. The Age of Reason . - Dover Publications, 2004 .-- S. 52.

- ↑ Eli Maor. Trigonometric Delights. - Princeton University Press, 1998 .-- P. 20. - ISBN 0-691-09541-8 .

- ↑ Glaser G.I., 1982 , p. 95.

- ↑ van der Waerden, Bartel Leendert. Geometry and Algebra in Ancient Civilizations . - Springer, 1983. - ISBN 3-540-12159-5 .

- ↑ Van der Waerden, 1959 , p. 13, footnote.

- ↑ Zverkina G.A. History of mathematics: Textbook. - M .: MIIT, 2005 .-- 108 p. : “Speaking of Egyptian geometry, it is natural to mention the“ Egyptian triangles ”- rectangular triangles with integer sides, also known in Mesopotamia. In land surveying, knowledge of such triangles made it possible to mark the right angles of land using a cord with knots tied on it at equal distance. ”

- ↑ 1 2 Glazer G.I., 1982 , p. 77.

- ↑ Zeiten G.G., 1938 , p. 124-125.

- ↑ Glaser G.I., 1982 , p. 94-95.

- ↑ 1 2 Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 92-96.

- ↑ Zeiten G.G., 1932 , p. 153-154.

- ↑ Veselovsky, 1961 , p. 38.

- ↑ Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. fifteen.

- ↑ Boyer, Carl B. A History of Mathematics. - Second ed. - John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1991. - P. 158-159. - ISBN 0-471-54397-7 .

- ↑ 1 2 Toomer, 1973 .

- ↑ Van der Waerden, 1988 .

- ↑ Sirazhdinov S.H., Matvievskaya G.P., 1978 , p. 77.

- ↑ Thurston, 1994 .

- ↑ Duke, 2011 .

- ↑ Reading book on the history of mathematics, 1976 , p. 195-197.

- ↑ Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 25-27.

- ↑ Duke, 2002 .

- ↑ Sidoli, 2004 .

- ↑ 1 2 Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 27-33.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 33-36.

- ↑ History of Mathematics, Volume I, 1970 , p. 141-142.

- ↑ Zeiten G.G., 1932 , p. 158-162.

- ↑ 1 2 Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 36-39.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 40-44.

- ↑ 1 2 3 History of mathematics in the Middle Ages, 1961 , p. 156-158.

- ↑ Glaser G.I., 1982 , p. 81-82.

- ↑ Scott JF, 1958 , p. fifty.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Sirazhdinov S. Kh., Matvievskaya G.P., 1978 , p. 79.

- ↑ 1 2 Scott JF, 1958 , p. 52.

- ↑ History of Mathematics, Volume I, 1970 , p. 199-201.

- ↑ History of Mathematics in the Middle Ages, 1961 , p. 157.

- ↑ Gupta, RC Second-order interpolation in Indian mathematics upto the fifteenth century (Eng.) // Indian Journal of History of Science: journal. - Vol. 4 , no. 1 & 2 . - P. 86-98 .

- ↑ 1 2 History of mathematics in the Middle Ages, 1961 , p. 160.

- ↑ History of Mathematics in the Middle Ages, 1961 , p. 159.

- ↑ Bakhmutskaya E. Ya. Power series for sint and cost in the works of Indian mathematicians of the 15th – 18th centuries // Historical and mathematical research . - M .: Fizmatgiz, 1960. - No. 13 . - S. 325—335 .

- ↑ Roy, Ranjan. Discovery of the Series Formula for π by Leibniz, Gregory, and Nilakantha // Math. Assoc. Amer. Mathematics Magazine - 1990. - Vol. 63 (5) . - S. 291-306 .

- ↑ Plofker, 2009 .

- ↑ History of Mathematics, Volume I, 1970 , p. 203.

- ↑ 1 2 Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 51-55.

- ↑ Reading book on the history of mathematics, 1976 , p. 204-205.

- ↑ History of Mathematics, Volume I, 1970 , p. 236-238.

- ↑ History of Mathematics, Volume I, 1970 , p. 234-235.

- ↑ Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 111.

- ↑ Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 96-98.

- ↑ Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 69.

- ↑ 1 2 Glazer G.I., 1983 , p. 60.

- ↑ Matvievskaya G.P., 2012 , p. 71-78.

- ↑ Reading book on the history of mathematics, 1976 , p. 195-198 ,.

- ↑ Sirazhdinov S.H., Matvievskaya G.P., 1978 , p. 82.

- ↑ Sirazhdinov S.H., Matvievskaya G.P., 1978 , p. 88.

- ↑ Tusi Nasireddin . A treatise on the full quadrilateral. Baku, ed. AS AzSSR, 1952.

- ↑ Rybnikov K.A., 1960 , p. 105.

- ↑ This treatise was included in Astronomy, one of the six parts of the fundamental theological-philosophical and scientific treatise “War of the Lord,” on which Gersonides worked throughout his life.

- ↑ Rabinovich, Nachum L. Rabbi Levy ben Gershom and the origin of the method of mathematical induction. = Rabbi Levi ben Gershom and the origins of mathematical induction // Archive for History of Exact Sciences . - 1970. - V. 6. - S. 237-248.

- ↑ Vileitner G., 1960 , p. 14, 30-31.

- ↑ Zeiten G.G., 1932 , p. 223-224.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Gleizer G.I., 1982 , p. 79, 84.

- ↑ History of Mathematics, Volume I, 1970 , p. 320.

- ↑ Stepanov N.N. §42. Formulas of “Napier analogy” // Spherical trigonometry. - M. — L .: OGIZ , 1948. - S. 87-90. - 154 p.

- ↑ 1 2 Vileitner G., 1960 , p. 341-343.

- ↑ Zeiten G.G., 1938 , p. 126-127.

- ↑ 1 2 Zeiten G.G., 1938 , p. 129.

- ↑ Alexandrova N.V., 2008 , p. 189.

- ↑ Rybnikov K.A., 1960 , p. 125.

- ↑ Zeiten G.G., 1938 , p. 130-132.

- ↑ Hirer E., Wanner G. Mathematical analysis in the light of its history. - M .: Scientific World, 2008. - P. 42. - 396 p. - ISBN 978-5-89176-485-9 .

- ↑ 1 2 Glazer G.I., 1982 , p. 86.

- ↑ Vileitner G., 1960 , p. 324-325.

- ↑ Zeiten G.G., 1938 , p. 283-288.

- ↑ Vileitner G., 1960 , p. 327-335.

- ↑ 1 2 History of Mathematics, Volume III, 1972 , p. 205-209.

- ↑ Вилейтнер Г., 1960 , с. 331.

- ↑ Цейтен Г. Г., 1938 , с. 419.

- ↑ Biography of Roger Cotes . The MacTutor History of Mathematics (февраль 2005). Архивировано 24 сентября 2012 года.

- ↑ Александрова Н. В., 2008 , с. 152.

- ↑ Александрова Н. В., 2008 , с. 80-81.

- ↑ Вилейтнер Г., 1960 , с. 322, 329.

- ↑ Александрова Н. В., 2008 , с. 207.

- ↑ Вилейтнер Г., 1960 , с. 334.

- ↑ Вилейтнер Г., 1960 , с. 345.

- ↑ Степанов Н. Н. Сферическая тригонометрия. - Ed. 2-е. — М.-Л.: ГИТТЛ, 1948. — С. 139-143. — 154 с.

- ↑ Александрова Н. В., 2008 , с. 211.

- ↑ История математики, том III, 1972 , с. 323.

- ↑ Вилейтнер Г., 1960 , с. 148, 336.

- ↑ История математики, том III, 1972 , с. 209-215.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Тригонометрический ряд // Математическая энциклопедия (в 5 томах) . — М. : Советская Энциклопедия , 1982. — Т. 5.

- ↑ 1 2 Паплаускас А. Б., 1966 , с. 7, 15.

- ↑ Глейзер Г. И. История математики в школе . — М. : Просвещение, 1964. — С. 287. — 376 с.

- ↑ См.: Юшкевич А. П. Главы по истории математики в средние века. — В кн.: История естествознания в России. М.: 1957, т. I, с 45—48.

- ↑ См. статью Б. А. Розенфельда в книге: Каган В. Ф. Основания геометрии. Том II, стр. 313—321.

- ↑ Паплаускас А. Б., 1966 , с. 26-27.

- ↑ Паплаускас А. Б., 1966 , Глава IV.

- ↑ Даубен, Джозеф У. Георг Кантор и рождение теории трансфинитных множеств // Scientific American, издание на русском языке. — 1983. — Вып. 8 (август) . — С. 76—86 .

- ↑ Тригонометрический ряд . Дата обращения 28 октября 2012. Архивировано 23 ноября 2012 года.

- ↑ Тригонометрический полином // Математическая энциклопедия (в 5 томах) . — М. : Советская Энциклопедия , 1982. — Т. 5.

- ↑ Braunmühl A. Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Trigonometrie. — Leipzig, 1900—1903.

Literature

- Books

- Александрова Н. В. История математических терминов, понятий, обозначений: Словарь-справочник, изд. 3-е. - SPb. : ЛКИ, 2008. — 248 с. — ISBN 978-5-382-00839-4 .

- Ван дер Варден Б. Л. Пробуждающаяся наука. Математика древнего Египта, Вавилона и Греции . — М. : ГИФМЛ, 1959.

- Вилейтнер Г. История математики от Декарта до середины XIX столетия . — М. : ГИФМЛ, 1960. — 468 с.

- Глейзер Г. И. История математики в школе. VII-VIII классы. Пособие для учителей. — М. : Просвещение, 1982. — С. 76-95. — 240 с.

- Глейзер Г. И. История математики в школе. IX-X классы. Пособие для учителей. — М. : Просвещение, 1983. — 352 с.

- История математики под редакцией А. П. Юшкевича в трёх томах, М.: Наука.

- История математики. С древнейших времен до начала Нового времени // История математики / Под редакцией А. П. Юшкевича , в трёх томах. — М. : Наука, 1970. — Т. I. — 351 с.

- Математика XVII столетия // История математики / Под редакцией А. П. Юшкевича , в трёх томах. — М. : Наука, 1970. — Т. II. — 300 с.

- Математика XVIII столетия // История математики / Под редакцией А. П. Юшкевича , в трёх томах. — М. : Наука, 1972. — Т. III. — 495 с.

- Матвиевская Г. П. Очерки истории тригонометрии: Древняя Греция. Средневековый Восток. Позднее Средневековье. - Ed. 2-е. — М. : Либроком, 2012. — 160 с. — (Физико-математическое наследие: математика (история математики)). — ISBN 978-5-397-02777-9 .

- Паплаускас А. Б. Тригонометрические ряды. От Эйлера до Лебега. — М. : Наука, 1966. — 277 с.

- Рожанская М. М. Механика на средневековом Востоке. — Москва: Наука, 1976.

- Рыбников К. А. История математики в двух томах. — М. : Изд. МГУ, 1960. — Т. I.

- Сираждинов С. Х., Матвиевская Г. П. Абу Райхан Беруни и его математические труды. Пособие для учащихся. — М. : Просвещение, 1978. — 95 с. — (Люди науки).

- Стройк Д. Я. Краткий очерк истории математики, изд. 3-е. — М. : Наука, 1978. — 336 с.

- Стройк Д. Я. (Dirk J. Struik). Краткий очерк истории математики, изд. 5-е. — М. : Наука, Гл. ed. физ.-мат. литературы, 1990. — 256 с. — ISBN 5-02014329-4 .

- Хрестоматия по истории математики. Арифметика и алгебра. Теория чисел. Геометрия / Под ред. А. П. Юшкевича . — М. : Просвещение, 1976. — 318 с.

- Цейтен Г. Г. История математики в древности и в средние века. — М.-Л.: ГТТИ, 1932. — 230 с.

- Цейтен Г. Г. История математики в XVI и XVII веках. — М.-Л.: ОНТИ, 1938. — 456 с.

- Юшкевич А. П. История математики в Средние века. — М. : ГИФМЛ, 1961. — 448 с.

- Plofker K. Mathematics in India. — Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Scott JF A History of Mathematics From Antiquity to the Beginning of the Nineteen Century. — London: Tailor & Francis Ltd, 1958. — 266 p.

- Thurston H. Early astronomy. — New York: Springer-Verlag, 1994.

- Van Brummelen G. The Mathematics of the Heavens and the Earth: The Early History of Trigonometry. — Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Articles

- Веселовский И. Н. Аристарх Самосский — Коперник античного мира // Историко-астрономические исследования, вып. VII. — М. , 1961. — С. 17—70 .

- Матвиевская Г. П. Сферика и сферическая тригонометрия в древности и на средневековом Востоке // Развитие методов астрономических исследований, Вып. 8. — М.-Л., 1979.

- Bond JD The Development of Trigonometric Methods down to the Close of the XVth Century // Isis. — 1921. — Vol. 4, № 2 . — P. 295—323.

- Duke D. Hipparchus' Coordinate System // Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. - 2002. - Vol. 56. — P. 427—433.

- Duke D. The Very Early History of Trigonometry // DIO: The International Journal of Scientific History. — 2011. — Vol. 17. — P. 34—42. Архивировано 26 марта 2012 года.

- Kennedy ES The history of trigonometry // Historical Topics for the Mathematics Classroom: Thirty-first Yearbook. — Washington, DC: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 1969.

- Moussa A. The trigonometric functions, as they were in the arabic-islamic civilization // Arabic Sciences and Philosophy. — 2010. — Vol. 20. — P. 93—104.

- Sidoli N. Hipparchus and the Ancient Metrical Methods on the Sphere // Journal of the History of Astronomy. — 2004. — Vol. 35. — P. 71—84.

- Toomer G. J. The Chord Table of Hipparchus and the Early History of Greek Trigonometry // Centaurus. - 1973. - Vol. 18. — P. 6—28.

- Van der Waerden B. L. Reconstruction of a Greek table of chords // Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. — 1988. — Vol. 38. — P. 23—38.

Links

- Федосова М. Тригонометрия . Энциклопедия Кругосвет. Дата обращения 5 июня 2012. Архивировано 24 сентября 2012 года.

- O'Connor, JJ; Robertson EF Trigonometric functions (англ.) . MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive (1996). Дата обращения 5 июня 2012. Архивировано 24 сентября 2012 года.

- Leo Rogers. The History of Trigonometry (англ.) . Дата обращения 19 октября 2012. Архивировано 28 октября 2012 года.