Pogrom in Kielce is the largest post-war pogrom against the Jewish population in Poland , carried out on July 4, 1946 by the anti - Semitic Polish population of the city of Kielce .

| The funeral of the dead. [one] | |

| The funeral of the dead. [2] | |

Content

Background

In post-war Poland, anti-Semitic sentiment was fueled by the widespread belief that Jews were supporters of the new regime , since post-war authorities condemned anti-Semitism , guarded the surviving Jews , among the representatives of the new government and the Polish Army were Jews. The second circumstance was the unwillingness to return to the Jews the property plundered by the Polish population during the war [3] [4] .

A memorandum from the Polish authorities in early 1946 stated that, from November 1944 to December 1945, 351 Jews were reportedly killed. Most of the killings took place in the Kielec and Lublin voivodeships, the victims were returning from concentration camps or former partisans . The report mentioned four types of attacks:

- attacks as a result of rumors about the killing of a Polish child ( Lublin , Rzeszow , Tarnow , Sosnovichi )

- blackmail to evict Jews or seize their property

- robbery killings

- murders that were not accompanied by robberies, in most cases committed by throwing grenades at Jewish shelters [5] .

The largest incident was in Krakow , where a pogrom occurred on August 11, 1945 , starting with throwing stones at a synagogue, and then escalating into attacks on houses and dormitories where Jews lived. Parts of the Polish and Soviet Army put an end to the pogrom. Among the Jews were killed and wounded. Israel Gutman in the study "Jews in Poland after the Second World War" writes that the pogroms were not the work of individual bandits and were carefully prepared [5] .

Pogrom

Before the start of World War II, about 20 thousand Jews lived in Kielce, which amounted to one third of the population of the city. After the war in Kielce, there were about 200 Jews who survived the Holocaust , most of them former prisoners of Nazi concentration camps . Most of the Kielce Jews were housed in Building 7 on Planty Street, where the Jewish committee and the Zionist Youth organization were located.

The reason for the start of the pogrom was the disappearance of an eight-year-old boy, Henryk Blashchik [6] . He disappeared on July 1, 1946 and returned two days later, saying that he had been abducted by Jews and, having hidden, intended to kill (later during the investigation it turned out that the boy was sent by his father to the village, where he was taught what he should tell) [5 ] .

On July 4, 1946, at 10 a.m., a massacre began, in which many people participated, including in military uniforms. By noon, about two thousand people gathered near the building of the Jewish Committee. Among the slogans that were heard were: “Death to the Jews!”, “Death to the murderers of our children!”, “Finish Hitler's work!” At noon, a group arrived at the building, led by police sergeant Vladislav Blakhut, who disarmed those who gathered to resist the Jews. As it turned out later, Blahut was the only representative of the police among those who entered [7] . When the Jews refused to go outside, Blahut began to beat them on the head with the handle of a revolver, shouting: "The Germans did not have time to destroy you, but we will finish their work." The crowd broke open the doors and shutters, the rioters entered the building and started killing with logs, stones and iron bars [7] .

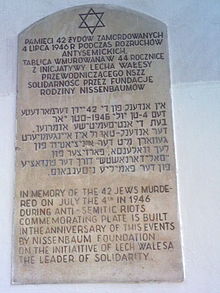

During the pogrom, from 40 [8] [9] [10] to 47 Jews [5] were killed, among them children and pregnant women, and more than 50 people were injured [11] .

Jews were beaten and killed not only in Planty, 7, but also in other places of the city.

Consequences

Already on July 9, 1946, twelve people were in the dock before the participants of the visiting session of the Supreme Military Court. The court decision was read on July 11 . Nine accused were sentenced to death , one each to life imprisonment , ten years and seven years in prison. The President of Poland, Boleslav Bierut, did not exercise his right of pardon , and those sentenced to death were shot .

The pogrom in Kielce caused a massive emigration of Jews from Poland. If in May 1946 3,500 Jews left Poland, in June - 8,000, then after the pogrom during July - 19 thousand, in August 35 thousand people [12] . Towards the end of 1946, the wave of departure subsided, as the situation in Poland returned to normal, almost no one was left, and the rest were not mobile.

In 1996 (the 50th anniversary of the pogrom), the mayor of Kielce apologized on behalf of the townspeople. On the 60th anniversary, the ceremony was raised to the national level, with the participation of the President and ministers. Polish President Lech Kaczynski called the pogrom in Kielce "a great shame for the Poles and the tragedy of the Jews."

During World War II, the Poles committed war crimes against their Jewish neighbors in at least 24 regions of the country. This conclusion was made by a government commission investigating the events in Poland related to the beginning of World War II. [13]

Provocation Versions

The Polish authorities accused the opposition of "reactionary elements" of provoking the pogrom. A number of senior officials in the province were replaced.

There are also a number of versions about the involvement in the organization of the pogrom of the Polish authorities and Soviet special services - among the crowd of rioters there were many soldiers and police officers, including police and public security officers (they were subsequently arrested and brought to trial: Major Sobchinsky, Colonel Kuznitsky (commandant of the voivodship office police), Major Gvyazdovich and Lieutenant Zagursky. Gvyazdovich and Sobchinsky were acquitted by the court). Proponents of these versions believe that the provocateurs benefited from discrediting the Polish opposition , which was attributed to the organization of the pogrom, and the pogrom itself became an occasion for repression and increased power of the communist government.

On July 19, 1946, the former chief military prosecutor, Henrik Holder, wrote in a letter to the deputy commander of the Polish army, General Marian Spychalski , that “we know that the pogrom was not only the fault of the police and the army, who were guarding the city of Kielce and around it, but also the fault of the member of the government who took part in this. ” [14]

American historian and sociologist of Polish descent Tadeusz Piotrowski [15] , Polish philosopher of Jewish descent and professor at the Institute of Philosophy of Warsaw University Stanislav Krajewski [16] , as well as the Polish Catholic priest of the Kielce diocese , sociologist and theologian Jan Siedzjanowski [17] are of the opinion that the pogrom in Kielce was a provocation of Soviet intelligence.

21st Century Investigations

In 1991-2004 The Kielec pogrom was investigated by the Commission for the Investigation of Crimes against the Polish People of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance [18] . The Commission (2004) established "the lack of evidence of the Soviet side's interest in provoking events " [19] .

The Polish writer Włodzimierz Kalitsky, based on the materials of the dissertation by B. Shainok, devoted to the reconstruction of the events of the pogrom, writes that three versions can really be considered:

* NKVD-controlled plot involving the Polish leadership

* No conspiracy at all

* The accession of special services to the pogrom, which began spontaneously, without political provocation

In his opinion, the latest version looks the most real.

Based on the materials of the FSB archive about the pogrom in Kielce in 2009, copies of the materials of the official investigation translated into Russian were published [20] .

On October 20, 2008, the Kielce regional daily Echo of the Day published information from a resident of the city who wanted to remain anonymous that on July 4, 1946, during a pogrom on Planty 7, soldiers in uniform killed 7 more Jews in Kielce (including at least one woman ) at the address st. Petrikovsk, 72 and their corpses were taken away by car. However, residents of neighboring houses did not hear anything about it. Prosecutor Krzysztof Falkevich said the message will be checked [21] .

See also

- The film " From Hell to Hell "

- Pogrom in Edwabna (1941)

- Pogrom in Krakow (1946)

Literature

- Jan Tomasz Gross. Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland After Auschwitz. - New York, NY: Random House, 2006 .-- 320 p. ISBN 0-375-50924-0 .

Links

- The last pogrom of Europe

- Sergey Seninsky. Anti-Semitism and Poland: History and Lessons (Inaccessible link) . Radio Liberty . Archived February 12, 2007.

- Dabrowski E. Reflections on the Jewish pogrom of 1946 in Kielce // Lechaim: journal. - May 2000. - Issue. 5 (97) .

- Certificate of the USSR Embassy in Poland on the state of the Jewish question in the country. September 24, 1946 "The Soviet factor in Eastern Europe 1944-1953. Documents ”Moscow, ROSSPEN, 1999.

- Kalitsky V. “The Keleck Tragedy” Part 1 , Part 2

- Poland honors the memory of the victims of the Kielce pogrom. 07/05/2006

Notes

- ↑ Jerzy Dabrowski “Reflections on the Jewish Pogrom of 1946 in Kielce”

- ↑ Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team: Kielce

- ↑ Poland commemorates the victims of the Kielce pogrom (inaccessible link)

- ↑ Extracts from cultural periodicals

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 The Holocaust of European Jewry. Part 6, Jerusalem, 1995, p. 251-253.

- ↑ Europe's latest pogrom. Archived copy of September 26, 2007 on the Wayback Machine . Alexander Dymelin. - Shoah. Information and analytical portal, 07/06/2006

- ↑ 1 2 Kahane D. After the Flood. Jerusalem. S.62.

- ↑ Anti-Jewish Riots in Poland (Eng.) // Times. - 1946. - No. July 4th - P. 4 .

- ↑ Engel D. Patterns Of Anti-Jewish Violence In Poland, 1944-1946 . - Jerusalem: Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies, 1998 .-- P. 1 .

- ↑ Williams, Anna The Kielce Pogrom . Date of treatment November 11, 2009. Archived January 21, 2012.

- ↑ Gutman I. Jews in Poland after the Second World War, Jerusalem, 1984, p. 31-35.

- ↑ The Holocaust of European Jewry. Part 6, Jerusalem, 1995, p. 222.

- ↑ It was only the beginning of the "Central Jewish Resource SEM40. Israel, Middle East, Jews

- ↑ By J. Śledzianowski, Wokół pogromu, p. 80

- ↑ Tadeusz Piotrowski . Postwar years // Poland's Holocaust . - McFarland & Company, 1997. - P. 136. - ISBN 0-7864-0371-3 .

- ↑ Stanislav Kraevsky . Jews and Communism // From The Polish Underground / Michael Bernhard, Henryk Szlajfer. - State College, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University , 2004. - P. 380. - ISBN 0-271-02565-4 .

- ↑ Jan Śledzianowski in Pytania nad pogromem kieleckim , p. 213 ISBN 83-7442-379-X (Polish)

- ↑ Wokół pogromu kieleckiego, red. Łukasz Kamiński, Jan Żaryn. Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, tom 26 . Warszawa, 2004 .-- 530 s.

- ↑ Jacek Żurek, “Śledztwo IPN w sprawie pogromu kieleckiego i jego materiały (1991-2004)” in Wokół pogromu kieleckiego, p. 136.

- ↑ Jewish pogrom in Kielce July 4, 1946 (Based on materials from the FSB archive). Publication, introductory article and comments by V. G. Makarov, V. S. Khristoforov. - Archive of Jewish History (Yearbook), Volume 5 . Ch. ed. O. V. Budnitsky. International Research Center for Russian and East European Jewry. ROSSPEN Publishing House (Russian Political Encyclopedia), 2009

- ↑ 'Maciągowski M. Wstrząsająca tajemnica domu przy Piotrkowskiej (Polish) // Echo of the day . - 20 października 2008.