The planetary model of the atom , or the Rutherford atom model , is a historically important model of the structure of the atom proposed by Ernst Rutherford in a classic article [1] published in 1911 based on the analysis and statistical processing of the results of experiments on the dispersion of alpha particles in thin gold foil made Geiger and Marsden in 1909

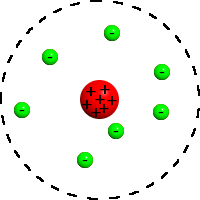

In this model, Rutherford describes the structure of an atom consisting of a tiny positively charged nucleus , in which almost the entire mass of an atom is concentrated, around which electrons rotate, just like planets move around the Sun.

The planetary model of the atom corresponds to the modern ideas about the structure of the atom with clarifications that the motion of electrons cannot be described by the laws of classical mechanics and has a quantum-mechanical description .

Historically, Rutherford's planetary model replaced the " plum pudding model " by Joseph John Thomson , which suggests that negatively charged electrons are placed inside a positively charged atom with a positive charge distributed throughout the atom, similar to the highlight in the pudding.

Background

By 1904, the Japanese physicist Nagaoka developed the early, as it turned out later, erroneous “planetary model” of the atom (“atom of Saturn type”) [2] . The model was built on the analogy with the calculations of the stability of the rings of Saturn (the rings are balanced due to the very large mass of the planet). Nagaoka’s model was wrong, but the two implications of it were prophetic:

- the nucleus of an atom is really very massive;

- electrons are held in orbit by electrostatic forces (just as Saturn's rings are held by gravitational forces ).

A new model of the structure of the atom Rutherford proposed in 1911 based on the analysis of experiments on the dispersion of alpha particles in gold foil, conducted in 1909 under his leadership [1] .

This scattering is large, unexpectedly statistically inexplicable, the amount of alpha particles was scattered at large angles, which indicated that the center of scattering is small, it has a significant electrical charge and the mass of the atom.

Rutherford’s calculations showed that the scattering center, positively or negatively charged, should be at least 3000 times smaller than the size of an atom, which at that time was already known and estimated to be about 10 −10 m. Since at that time the electrons were already known, and their mass and charge are determined, then the scattering center, which was later called the nucleus, should have a charge opposite to the electrons. Rutherford did not associate the magnitude of the charge with the atomic number. This conclusion was made later. And Rutherford himself suggested that the nuclear charge is proportional to the atomic mass . The connection of the electric charge of the nucleus with the atomic number of the chemical element was established by Henry Mosley in experiments carried out in 1913.

The disadvantage of the planetary model was the impossibility of explaining atomic stability by it. From classical electrodynamics, it follows that as electrons move around the nucleus, experiencing centripetal acceleration as planets around the Sun, they must radiate electromagnetic waves according to the laws of classical electrodynamics, losing the kinetic energy of orbital motion to radiation and, as a result, core. Calculations performed using the methods of classical electrodynamics show that electrons must “fall” onto the nucleus in a time of the order of 10–11 s.

This contradiction was removed by the subsequent development of the planetary model in the model of the Bohr atom, which postulates other laws of the orbital motion of electrons based on de Broglie , different from the classical laws. The conclusions of classical electrodynamics completely contradicting the experiment could explain the development of quantum mechanics .

Notes

- 2 1 2 Rutherford E. The Scattering of α and β Particles by Matter and the Atom , Philosophical Magazine. Series 6, vol. 21 . May 1911

- ↑ Bryson, Bill. A Short History of Nearly Everything. - Broadway Books, 2003-05-06. - ISBN 0767908171 .