The murder of Julia Martha Thomas ( Eng. Murder of Julia Martha Thomas ; the press also called the “secret of Barnes” or “Richmond murder”) is one of the most famous crimes in England at the end of the 19th century. Julia Thomas, a widow of about fifty years old who lived in Richmond in southwest London, was killed on March 2, 1879 by her maid, Kate Webster, a thirty-year-old Irish woman who had a criminal past. To get rid of the body, Webster dismembered it, boiled the meat from the bones and threw most of the remains into the Thames . There were rumors (not confirmed) that she was offering fat cut from the body of the murdered woman to her neighbors and street children. Part of the remains of Thomas were found in the river. The victim’s head was found only on October 22, 2010 - the skull was discovered during construction work carried out for the famous TV presenter David Attenborough .

After the murder, Kate Webster impersonated Julia Thomas for two weeks, but was exposed and fled to Ireland and took refuge in her uncle's house in Killann (near Enniscorty in Wexford County). There, on March 29, she was arrested and sent to London, where in July 1879 she appeared before the Old Bailey court. After a six-day trial, she was found guilty and sentenced to death. Trying to avoid the death penalty, she declared at the last minute that she was pregnant, but the jury, consisting of married women, rejected her request. Webster was hanged on July 29 at Wandsworth Prison by executioner William Marwood. On the night before the execution, she confessed to the murder. The case attracted great public attention and was widely covered by the press of Great Britain and Ireland. The actions of Webster after the commission of the crime and during the trial contributed to the growth of the case.

Content

Background

Julia Marta Thomas was a teacher and widowed twice. After the death of her second husband in 1873, she lived alone in Richmond on Park Road in Mayfield cottages (sometimes called Vine cottages), in house No. 2. The house was a two-story, semi-detached townhouse made of gray stone, from the front and rear of which there were gardens. At that time, the district was not densely populated, although there was a pub near her house called “ The Hole in the Wall ” [1] .

George Henry Rudd, Julia Thomas's doctor, described her as a “small, well-dressed lady” for about fifty-four years [2] . According to Elliot O'Donnell, who collected in his introduction to deciphering Webster’s trial recordings testimonies of her contemporaries, Thomas had an “excitable temperament” and was considered eccentric. She often traveled without telling her friends and relatives about her whereabouts for weeks or months [3] . Thomas belonged to the "lower" middle class and, accordingly, was not rich, but dressed up and wore jewelry to give the impression of a wealthy woman. Her desire to hire a maid is probably due to the same desire to gain a certain status in society, as well as practicality. She had a reputation as a harsh mistress. Her irregular habits made it difficult for her to find and retain employees. Until 1879, she managed to keep at her work only one servant for a long time [4] .

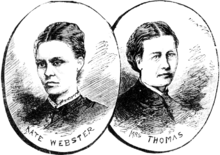

On January 29, 1879, Thomas hired Kate Webster as a maid. Webster, née Kate Lawler, was born in Killann , County Wexford, around 1849 . Later, The Daily Telegraph described her as “a tall, tightly knocked down woman five feet and five inches (165 cm) tall, with yellow skin covered with a lot of freckles, and with large and prominent teeth” [3] . The details of her early life are unknown, as many of her later autobiographical statements turned out to be unverified, but she claimed to be married to a sailor, a captain named Webster, from whom she had four children. According to her, in a short time all the children died, as did the husband. In December 1864, at the age of fifteen, Webster was imprisoned in Wexford for theft [5] . In 1867, she came to England [6] . In February 1868, she was sentenced to four years in hard labor for a similar crime [7] in Liverpool .

In January 1872, Webster was released from prison and in 1873 moved to Rose Gardens in Hammersmith , London, where she became friends with the neighboring Porter family [8] . April 18, 1874 in the city of Kingston upon Thames, she gave birth to a son, whom she named John W. Webster [9] . Her father’s identity is unknown, as she mentioned three different men at different times. One of them, named Strong, was her accomplice in further thefts and robberies. She later stated that she was in a hopeless situation, because “after Strong left her, she was forced to commit crimes in order to support herself and her child” [10] . She often moved to West London, using different names: Webb, Webster, Gibbs, Gibbons and Lawler. Living in Teddington, she was arrested and convicted in May 1875 of thirty-six charges of embezzlement. She was sentenced to eighteen months in Wandsworth Prison . Shortly after leaving prison, she was again arrested for embezzlement and in February 1877 was sentenced to imprisonment for another twelve months [11] . In her absence, Sarah Chris, a friend who worked as a cleaner for Miss Lauder in Richmond, looked after her young son. [7]

In January 1879, Sarah Chris, who worked at Lauder's house, became ill, and Webster temporarily replaced her. Lauder was a friend of Julia Martha Thomas and knew of her desire to find a maid. She made a recommendation to Webster [12] . Thomas hired Webster, and apparently did not make inquiries about the past of her new maid [13] . Soon, the relationship between the two women quickly deteriorated. Thomas did not like the way Webster worked, and she often criticized her. Webster later said:

At first I thought she was a nice old lady ... but I found her very demanding, and she did many things to bother me during work. When I finished my work in my rooms, she followed me and indicated the places where, according to her, I did not clean, which indicated a hostile attitude towards me.

Original textAt first I thought her a nice old lady ... but I found her very trying, and she used to do many things to annoy me during my work. When I had finished my work in my rooms, she used to go over it again after me, and point out places where she said I did not clean, showing evidence of a nasty spirit towards me.- [14]

In turn, Webster became increasingly outraged by her mistress to such an extent that Thomas tried to persuade her friends to stay with her, because she did not like to be alone with Webster. It was decided that Webster would quit on February 28 [12] . Thomas noted her decision, this entry was the last in her diary: "Catherine warned of dismissal."

Murder

Webster persuaded Thomas to let her stay at work for another three days, until Sunday , March 2 . That day, she was due to leave for half a day and return on time to help Thomas prepare for evening service at the local Presbyterian church. This time, however, Webster visited a local pub and returned late, delaying Thomas's departure. The women quarreled, some parishioners later reported that Thomas seemed “very excited” in the church [12] . She told a friend of the parishioner that she had been late, “because her maid had negligently returned in time,” and that Webster, having received a rebuke, “became terribly angry” [15] . Thomas returned home early (around 9 pm) and entered into an argument with Webster. According to Webster’s final confession:

Mrs. Thomas came in and went upstairs. I got up after her, and we had a dispute that turned into a quarrel. In anger and rage, I pushed her from the top of the stairs to the first floor. She fell heavily, and I got scared at the sight of what happened, lost all control of myself, and in order to prevent her from screaming and bring me to trouble, I grabbed her by the throat, in the fight she was strangled, and I threw her at floor.

Original textMrs. Thomas came in and went upstairs. I went up after her, and we had an argument, which ripened into a quarrel, and in the height of my anger and rage I threw her from the top of the stairs to the ground floor. She had a heavy fall, and I became agitated at what had occurred, lost all control of myself, and, to prevent her screaming and getting me into trouble, I caught her by the throat, and in the struggle she was choked, and I threw her on the floor ..- [16] .

Neighbors, housewife Thomas, Eve, and her mother, heard one muffled sound, similar to the sound of a chair falling, but then did not pay attention to it [17] . In the house, Thomas Webster began to get rid of the body: she dismembered and cooked it in a laundry boiler and burned the bones in the hearth. She later described her actions:

I decided to do my best to get rid of the body. I separated my head from my body with a razor, which I then used to cut flesh. I also used a saw and a meat cutting knife to cut through the body. I prepared a pot of water to cook the body and prevent recognition; as soon as I managed to cut the body, I put the pieces in the cauldron and cooked them. I opened my stomach with a knife and burned as many parts as I could.

Original textI determined to do away with the body as best I could. I chopped the head from the body with the assistance of a razor which I used to cut through the flesh afterwards. I also used the meat saw and the carving knife to cut the body up with. I prepared the copper with water to boil the body to prevent identity; and as soon as I had succeeded in cutting it up I placed it in the copper and boiled it. I opened the stomach with the carving knife, and burned up as much of the parts as I could ..- [16] .

Neighbors noticed an unusual, unpleasant smell [18] . Webster later spoke of how she had to “endure the terrible sight that opened before me and the smell” [16] . However, activity at Mayfield Cottages, 2, did not seem out of the ordinary, as in many households it was customary to start washing on Monday early in the morning [18] . In the following days, Webster continued to clean Thomas' house and clothes, creating the appearance of ordinary everyday life for people who came to order. She packed the dismembered remains of Thomas in a black Gladstone bag and a cardboard box for a hat tied with a rope [19] . She was unable to fit the head and one leg of the murdered woman into containers, so she got rid of them separately. She threw her foot in a garbage dump in Twickenham [18] , and buried her head near Thomas's house at the stable of the Hole in the Wall pub, and her head was found 131 years later.

On March 4, Webster traveled to Hammersmith to her old neighbors, the Porters, whom she had not seen for six years. Webster wore a Thomas silk dress; she took with her a bag full of Thomas's remains. Webster introduced herself to the Porters as "Mrs. Thomas." She claimed that since the last meeting with them, she married, gave birth to a child, widowed and inherited a house in Richmond from her aunt. She invited Porter and his son Robert to the Oxford and Cambridge Arms Pub in Barnes. [20] On the way, she got rid of the bag, maybe she threw it into the Thames while the Porters were in the pub [19] . The bag was never found. Webster then asked young Robert Porter if he could help her drag a heavy box from her house at Mayfield Cottages to the station. When they crossed the bridge, Webster threw the box at the Thames. She managed to explain her actions to Robert and not arouse his suspicions [18] .

The next day, the box was found in shallow water near a river bank a mile downstream. He was found by the coal carrier Henry Wheatley, at seven in the morning he rode his wagon past the Barnes railway bridge. At first he thought that there might be stolen things in the box [21] . Whitley pulled out the box and opened it, finding that there were parts of the body wrapped in brown paper [22] . The find was immediately reported to the police, the remains were examined by a doctor who determined that the remains consist of a torso (without viscera) and a woman’s leg (one foot was missing). The head was absent; later it was suggested that Webster got rid of the head by throwing it into the river [23] . Around the same time, a human foot with an ankle was found in Twickham. Although it was clear that the foot and ankle belonged to the same body, nothing connected the finds with the victim, it was not possible to identify them [18] . The doctor who examined the remains mistakenly attributed them to a “young victim with very dark hair” [22] . The inquest on March 10-11 led to the recognition of the fact of committing a crime without establishing a criminal [24] . Unidentified remains were buried on March 19 at the Barnes Cemetery [25] . The press gave the unsolved murder the name "Barnes' Secret" [26] ; it was rumored that the body was used to dissect and study anatomy [22] .

It was later claimed that Webster was offering neighbors two pots of lard, allegedly obtained from the cooking of Thomas's remains. Nevertheless, no evidence was presented at a subsequent trial, which allows us to take this story as a legend, moreover, there are several versions of this story [23] . The owner of a nearby pub said Webster came to her and tried to sell what she called "the best fat." Leonard Reginald Grible, a criminologist, commented on this message: “there is no acceptable evidence that such disgusting trade took place”; most likely, this episode is on a par with stories from an extensive collection of false stories about the participants and victims of famous crimes [27] .

Arrest

Webster continued to live at 2 Mayfield Cottages, impersonating Thomas. She wore the clothes of her last employer and did business with merchants under a new guise. On March 9th, she agreed with local innkeeper John Church to sell furniture and other property, Thomas, to furnish his Rising Sun Pub. He agreed to pay 68 pounds along with an advance of 18 pounds. [28] By the time the wagons arrived on March 18, the suspicions of neighbors who had not seen Thomas for almost two weeks had begun to grow. Her neighbor in the townhouse, Miss Yves, asked the carriers who authorized the removal of the goods. They replied, “Mrs. Thomas,” and pointed to Webster. Realizing that she had been exposed, Webster immediately took to flight, having caught a train to Liverpool, and from there she left for her family home in Enniscorty. Church, meanwhile, realized that he had been deceived. When he searched Thomas's clothes in the van, he found a letter addressed to genuine Thomas. They called the police, who searched the house. Police found traces of blood, burned bones of fingers and deposits of fat behind the boiler, found a letter left by Webster, which gave the police the home address of a criminal in Ireland. Police immediately sent a wanted notice describing Webster and her son [29] .

Scotland Yard detectives soon found that Webster and his son sailed to Ireland aboard a coal steamer. The chief constable of the Royal Irish Police (RIC) in Wexford found that the woman Scotland Yard was looking for was arrested 14 years ago by his men for embezzlement. Irish police found her uncle's farm in Killand near Enniscorti [5] and on March 29 arrested the criminal [30] . She was taken to Kingstone (now Dun Leare) and from there sent to Richmond under police escort from Scotland Yard [31] . Upon learning that Webster was accused of murder, her uncle refused to shelter her son, and authorities sent the boy to the local workhouse, where he was supposed to be until he was found a place in an industrial school [31] .

Court and Sentence

The killing was a sensation on both sides of the Irish Sea. Many deliberately came to Richmond to take a look at Mayfield cottages. [31] When the arrested Webster was taken from Eniskorty to Dublin, crowds of people gathered at almost every station to look at the criminal and mock her. [32] According to the Manchester Guardian , preliminary hearings at the magistrate’s trial were attended by “many privileged and curious individuals ... including several ladies” [33] . The Times reported that when Webster first appeared at the trial of Richmond Magistrates, “there was a huge crowd around the building ... there was a lot of excitement” [34] .

On July 2, 1879, Webster appeared before the Old Bailey Central Criminal Court. Due to the great interest of the public in the case, the prosecution team was led by solicitor general Sir Harding Giffard. Webster defended a prominent London lawyer Warner Sleikh, the trial was chaired by George Denman [35] . The court attracted the same attention as the hearings in Richmond, aroused the interest of all walks of life. Кронпринц Швеции (будущий король Густав V ) следил за ходом процесса с четвёртого дня [36] .

В течение шести дней суд заслушивал показания свидетелей, на основании чего была сложена история гибели Томас. Перед началом судебного процесса Вебстер пыталась обвинить трактирщика Джона Чёрча и своего бывшего соседа Портера, но у обоих было прочное алиби и они были очищены от какой бы то ни было причастности к убийству [37] . Вебстер заявила, что невиновна, защита сделала упор на косвенном характере доказательств, а её привязанность к сыну, по версии защиты, доказывала, что она не способна на убийство [38] . Однако непопулярность Вебстер в обществе, её невозмутимый вид и безучастность защиты сыграли свою роль. Особенный удар по обвиняемой нанесла шляпница Мария Дарден, которая показала на суде, что Вебстер навестила её за неделю до убийства и сказала, что собирается поехать в Бирмингем, чтобы продать часть имущества, ювелирные украшения и дом, который ей оставила тётя. Коллегия присяжных восприняла это как знак того, что Вебстер задумала убийство заранее [39] , и осудила её после совещания, занявшего час с четвертью [40] .

Execution

После того, как жюри вынесло вердикт, и перед вынесением приговора судьёй, Вебстер спросила, есть ли какой-либо способ избежать смертной казни. Она заявила, что беременна, в очевидной попытке избежать смертной казни [41] . Как сообщала The Law Times , «появилась неуверенность, если не замешательство, что, конечно, совсем не соответствовало торжественности случая». Судья заявил, что «за тридцать два года своей работы он никогда не сталкивался с таким вопросом». В итоге секретарь суда предложил прибегнуть к устаревшей коллегии матрон, набранной из женщин, присутствовавших на заседании, чтобы определиться с вопросом, был ли у Вебстер «подвижный плод». Двенадцать женщин были приведены к присяге вместе с хирургом по имени Бонд. Они сопроводили Вебстер в отдельную комнату для обследования, которое заняло всего лишь пару минут [42] . Они вернулись с вердиктом, что у Вебстер нет «подвижного плода» хотя это не обязательно означало, что она не была беременной, эта разница побудила председателя общества акушеров Лондона выразить протест против использования «устаревшего в медицине предположения, что не рождённый ребёнок не является живым, пока мать не будет ощущать его движения» [43] .

За несколько дней до назначенной казни министр внутренних дел Ричард Кросс подал от лица Вебстер апелляцию, которая была отклонена с официальным заявлением, что после рассмотрения предложенных доводов министру «не удалось показать какие-либо достаточные основания, чтобы оправдать его совет Её величеству вмешаться в ход закона» [44] .

Before the execution, Webster made two plea pleas. She tried to blame Strong, the father of her child, stating that he had been involved in the murder and was responsible for involving her in a criminal life. On July 28, the night before the execution, she recanted her first confession, saying that she alone was guilty of a crime and admitted that Church, Porter and Strong had nothing to do with him [39] . The next day, at 9 am, she was hanged by executioner William Marwood, who used the newly invented “long fall” technique, which caused instant death [45] . After death was certified, the body was buried in an unmarked grave on one of the prison's courtyards. The crowd, waiting outside, greeted the black flag rising above the walls of the prison, which meant that the sentence was carried out [46] .

The day after the execution of Webster at Mayfield Cottages 2, an auction was held to sell Thomas property. The innkeeper John Church tried to buy Thomas furniture, including her other personal belongings, including her pocket watch and the knife that split Thomas's body. The boiler in which Thomas's body was welded was sold for six shillings [47] . Other auction visitors took pebbles and twigs from her garden as souvenirs. The house remained uninhabited until 1897 , since no one wanted to live where the murder took place. According to the tenant, even then the servants were reluctant to work in a house that was notorious [48] . Later, there were rumors that at the place where Thomas was buried, one could see the ghost of a nun [49] .

Skull Detection Thomas

In 1952, naturalist David Attenborough and his wife Jane purchased a house between the former Mayfield cottages (which have survived to the present) and the Hole in the Wall pub, which was abandoned after its closure in 2007 . In 2009, Attenborough acquired it for subsequent restoration [50] .

On October 22, 2010, excavators at an old pub discovered a “dark round object,” which turned out to be a female skull. It was buried under a foundation that stood for at least 40 years from the side of the pub stables. Rumors spread immediately that it was the skull of Julia Martha Thomas. The coroner demanded that the Richmond police conduct an investigation: determine the identity and circumstances of her death [51] .

Radiocarbon analysis conducted by specialists from the University of Edinburgh showed that the skull belonged to a person who lived between 1650 and 1880 , but the skull itself was discovered above a layer of Victorian tiles. The marks found on the skull coincided with Webster's story about how she threw her victim from the stairs. There was not much collagen, which is consistent with the version about boiling the remains of Thomas. In July 2011, the coroner concluded that the skull belonged to Julia Thomas. DNA analysis was impractical because Thomas died childless, and her relatives could not be calculated; in addition, there were no records of where her body was buried [52] .

The coroner issued a verdict of "unlawful killing", closing an open verdict issued in 1879 . The cause of death for Thomas was named asphyxiation and head injury. The police called the outcome “a good example of how good old-fashioned detective work, historical records, and scientific and technological progress together revealed the“ secret of the Barnes ”” [53] .

Community Impact

The murder had a notable impact on Victorian society in England and Ireland. The event caused a sensation and was widely covered by the press. The Dublin Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser called the crime “one of the most sensational and terrible chapters of the annals of human malice,” the press “teeming with detailed descriptions and details of this terrible crime” [32] . Webster was so popular that a few weeks after her arrest at the Madame Tussauds museum, they exhibited her wax figure for those who wanted to see the "Richmond killer" [3] . The statue was exhibited in the twentieth century, along with images of other famous killers - a pair of Burke and Her and Dr. Crippen [54] . A few days after the killer’s death, an entrepreneurial publisher from Strand issued a souvenir booklet called Kate Webster’s Life, Judgment, and Execution, which sold for a penny. It was advertised as “containing twenty colorful pages describing her full story with the judge’s closing speech, verdict and interesting information, along with her last words and engraving of her full page execution ( Portraits, Illustrations & c )” [55] . The weekly newspaper The Illustrated Police News published a souvenir cover with episodes of the last day of Webster’s life: “visiting a prisoner by friends”, “binding hands”, final rites “raising the black flag” and. finally, “filling the coffin with lime” [56] .

The case was reflected in street ballads laid on the melodies of popular songs. Soon after Webster’s arrest, Southwark printer and publisher G. Sach wrote the ballad Murder and Mutilation of an Old Lady near Barnes , based on the motive of the popular civil war song in the United States, “For a moment” before the battle, mother ”( Eng. Just Before the Battle, Mother ) [57] . Towards the end of the process, Sach wrote another ballad to the tune of the song “ Driven from Home ”:

The terrible crime at Richmond at last,

On Catherine Webster now has been cast,

Tried and found guilty she is sentenced to die.

From the strong hand of justice she cannot fly.

She has tried all excuses but of no avail,

About this and murder she's told many tales,

She has tried to throw blame on others as well,

But with all her cunning at last she has fell [58] .

Webster appeared to be a vicious, desperate and reckless woman [59] , and her crime - both monstrous and scandalous. First of all, respect was expected from the servants, the act of violence of the extreme degree shown by Webster against his mistress aroused deep concern. At that time, about 40% of women worked as domestic workers in the general population, from the richest homes to respectable working-class families. Servants and their owners lived and worked in the immediate vicinity, the honesty and diligence of the servants were a constant cause for concern [37] . Servants were paid very poorly, theft was common. If Webster had managed to sell Thomas Church furniture to John Church, she would have received an amount equivalent to her wage for 2-3 years [60] .

Another reason for the negative attitude towards Webster was her attempt to impersonate Thomas. For two weeks, she played the role of a woman from the middle class, for which she needed to behave properly and dress accordingly. The innkeeper John Church, whom Webster was trying to blame, was himself a servant at one time and achieved an increase in social status through the effective management of his pub. To achieve success, change his position through work was the norm of that time. Webster, by contrast, briefly assumed the guise of a middle-class representative [37] .

Many Victorians may have been thrilled that Webster violated accepted femininity standards. The ideal of that era is a highly moral, passive, physically weak woman [60] . Webster seemed the exact opposite of this ideal and was painted in the blackest colors, emphasizing her lack of femininity. Eliot O'Donnell, in an introduction to deciphering court records, described Webster as “not only cruel, fierce and shocking ... but the darkest of gloomy characters, a person so ominous and barbaric that it is difficult to perceive it as human” [61] . In the newspapers, Webster was called “gloomy, repulsive and ...”, although a reporter from The Penny Illustrated Paper and Illustrated Times commented that she was “not as unpleasant as they described” [62] .

Webster’s appearance and behavior were perceived as key attributes of her criminal nature. It was believed that crimes were committed by the “scum” of society, which are at the bottom, “criminals-repeat offenders” who prefer living in drunkenness and theft of thrift and hard work [60] . Her strong physique, possibly the result of hard physical labor, which she earned a living from, went against the idea of the majority of the middle class that women are inherent to physical weakness. Some commentators saw in her features a proof of her criminal nature. O'Donnell noted that her "squinting eyes," as he announced, "are often found among killers ... this feature, which I consider itself sufficient as one of the natural danger signals, warning people to stay away from her" [63] .

Webster's conduct in court and the details of her personal life also set society against her. Reporters everywhere described her as “calm” and “impassive” [64] . Webster lost her calm only once when it came to her son. This contradicted the established notion of a “decent woman,” who, in this situation, should have shown repentance. A series of male friends, one of whom became the father of her illegitimate child, suggested an erratic sex life, which again went against the norms of behavior. During the trial, Webster unsuccessfully tried to attract sympathy by denouncing Strong, the father of her child, because he had led her astray. “I had a close relationship with someone who was supposed to protect me and keep me away from evil ties and bad comrades” [60] . With her complaint, Webster played on public perceptions that a woman’s moral sense is inextricably linked to her sexual purity — a sexual “fall” should have led to a fall in other areas. A man who has a sexual relationship with a woman, thereby pledged social obligations that he had to fulfill. Webster’s attempt to blame the three innocents also provoked outrage. O'Donnell notes that “the society, without a doubt, completely condemned Kate Webster, perhaps both for trying to drag three innocent people to the scaffold and for killing on its own” [44] .

According to Shani d'Cruz of the Feminist Crime Research Network, the fact that Webster was Irish played a significant role in relation to her in the UK. Many Irish emigrated to England after the Great Famine and were faced with widespread prejudice. The British and the Irish were associated with drunkenness and crime, they were not considered people. There have been repeated episodes of violence between the English and Irish workers, the attacks of the Fenians (Irish separatists) in England. Webster’s demonization as “almost non-human” (according to O'Donnell) has become part of the public and legal perception of the Irish as natural criminals [65] .

See also

- Murder in the Red Barn

- William Henry Bury

- Frederick Bailey Dimming

Notes

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 13.

- ↑ Rudd, 1916 , p. 84.

- ↑ 1 2 3 O'Donnell, 1925 , p. ten.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 14.

- ↑ 1 2 The Barnes Mystery // Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper. - 1879. - March 30.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 58.

- ↑ 1 2 Wilson, 1971 , p. 193.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 7.

- ↑ The Barnes Mystery // The Belfast News-Letter. - Belfast, 1879. - April 2. - P. 5.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. eight.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 9.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Wilson, 1971 , p. 194.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 15.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. nineteen.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 23.

- ↑ 1 2 3 O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 68.

- ↑ D'Cruze et al., 2006 , p. 53.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Rudd, 1916 , p. 87.

- ↑ 1 2 Rudd, 1916 , p. 89.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 33.

- ↑ <B. N.> // The Manchester Guardian. - 1879. - March 10.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Supposed Murders // The Times. - 1879. - March 11. - P. 5.

- ↑ 1 2 Wilson, 1971 , p. 195.

- ↑ The Barnes Mystery // Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper. - 1879. - March 23.

- ↑ The Barnes Mystery // The Manchester Guardian. - 1879. - March 30.

- ↑ Rudd, 1916 , p. 83.

- ↑ Gribble, 1957 , p. 69.

- ↑ Wilson, 1971 , p. 196.

- ↑ The Barnes Mystery // The Manchester Guardian. - 1879. - March 27. - P. 7.

- ↑ The Barnes Mystery // The Manchester Guardian. - 1879. - March 30. - P. 6.

- ↑ 1 2 3 The Alleged Murder at Richmond // The Times. - 1879. - March 31. - P. 11.

- ↑ 1 2 The Barnes Mystery // Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser. - 1879. - March 31.

- ↑ The Richmond Murder // The Manchester Guardian. - 1879. - April 10. - P. 6.

- ↑ The Murder at Richmond // The Times. - 1879. - April 1. - P. 5.

- ↑ Gaute & Odell, 1983 , pp. 83, 87.

- ↑ The Richmond Murder // The Manchester Guardian. - 1879. - July 6. - P. 6.

- ↑ 1 2 3 D'Cruze et al., 2006 , p. 55.

- ↑ Conley, 2006 , pp. 84–85.

- ↑ 1 2 Wilson, 1971 , p. 198.

- ↑ Rudd, 1916 , p. 97.

- ↑ Rudd, 1916 , p. 98.

- ↑ Rudd, 1916 , p. 100.

- ↑ Oldman, 2006 , p. 110-111.

- ↑ 1 2 O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 66.

- ↑ Bailey, 1993 , p. 100.

- ↑ The Richmond Murder // The Illustrated Police News. - 1879. - August 2. - P. 4.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 73.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 82.

- ↑ Miller, 1986 , p. 66.

- ↑ Smith, Giles . What comes naturally, The Daily Telegraph (December 31, 2001).

- ↑ Fleming, Christine. . Inquest opens into skull found in Sir David Attenborough's garden, Richmond and Twickenham Times (October 26, 2010).

- ↑ Head found in David Attenborough's garden was murder victim, The Daily Telegraph (July 5, 2011).

- ↑ 'Barnes mystery' of Attenborough garden skull solved, BBC News (July 5, 2011).

- ↑ Carver, 2003 , p. 227.

- ↑ Advertisement // The Illustrated Police News. - 1879. - August 9. - P. 8.

- ↑ Execution of Catherine Webster at Wandsworth Gaol // The Illustrated Police News. - 1879. - August 2. - P. 1.

- ↑ Such, H. Murder and Mutilation of an Old Lady near Barnes. - circa April 1879.

- ↑ Such, H. Trial and Sentence of Catherine Webster // The Barnes Murderess. - 1879. - July.

- ↑ D'Cruze et al., 2006 , p. 52.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 D'Cruze et al., 2006 , p. 56.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 2.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. eleven.

- ↑ O'Donnell, 1925 , p. 12.

- ↑ D'Cruze et al., 2006 , p. 57.

- ↑ D'Cruze et al., 2006 , p. 56-57.

Literature

- Bailey, BJ Hangman: From Ketch to Pierrepoint, 300 Years of Execution. - L .: True Crime, 1993 .-- ISBN 978-0-86369-623-7 .

- Carver, SJ The Life and Works of the Lancashire Novelist William Harrison Ainsworth, 1850–1882. - Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2003 .-- ISBN 978-0-7734-6633-3 .

- Castleden, R. Serial Killers: They Live to Kill. - L .: Time Warner, 2005. - ISBN 978-0-316-73252-9 .

- Conley, C. Certain Other Countries: Homicide, Gender, and National Identity in Late Nineteenth-Century England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. - Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press , 2006 .-- ISBN 978-0-8142-1051-2 .

- D'Cruze, S .; Walklate, S .; Pegg, S. Murder: Social and Historical Approaches to Understanding Murder and Murderers. - Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing, 2006 .-- ISBN 978-1-84392-169-1 .

- Gaute, JHH; Odell R. Lady Killers. - Bath, England: Chivers Press, 1983. - P. 83. - ISBN 978-0-8511-9885-9 .

- Gribble, LR Famous Judges and Their Trials: A Century of Justice. - L .: J. Long, 1957.

- Miller, H. London Cemeteries: An Illustrated Guide and Gazetteer. - Ashgate Publishing Limited, 1986. - ISBN 978-0-85967-726-4 .

- O'Donnell, E. The Trial of Kate Webster. - Edinburgh: William Hodge & Company, 1925.

- Oldman, J. Trial by Jury: The Seventh Amendment and Anglo-American Special Juries. - N. Y .: NYU Press , 2006 .-- ISBN 978-0-8147-6204-2 .

- Rudd, GH Kate Webster's Revenge // Survivors' Tales of Famous Crimes / ed. by W. Wood. - L .: Cassell & Company, 1916.

- Wilson, P. Murderess: A Study of the Women Executed in Britain Since 1843. - L .: Michael Joseph, 1971. - ISBN 978-0-7181-0859-5 .

Links

- Catherine Webster . Murderpedia. Date of treatment April 7, 2014.