The generic name Babakotia comes from the Malagasy word babakoto - the common local name for the Indri lemur (as shown in the “ Discovery and Systematics ” section, indri is a close relative of the sloth lemurs , which include babakotia). The species name radofilai was given to the only known species in honor of a native of France, mathematician Jean Radofilao (Duflo). Radofilao showed a keen interest in exploring the caves, where later the first remains of babacotia were discovered, and compiled their map [2] .

Babacotia, represented by the only known species of Babakotia radofilai , belong to the Paleopropitec family, also known as sloth lemurs. The family includes three more genera, all extinct: archaeoindri , mesopropithecus, and paleopropithecus . The Paleopropithecus family is part of the infra- order Lemuridae , uniting all Madagascar lemurs [3] .

Babacotia is the last of the Paleopropithecus open genera, the description of which helped to better understand their (and, in particular, the smaller mesopropithecus genus) differences from Indri [3] . The first subfossil remains of babacotia were discovered during a series of expeditions organized by the anthropologist Alvin Simons from the early 1980s [4] . The remains were discovered in the cave of Antsiroandoha on the Ankaran plateau in northern Madagascar. The found remains belonged to more than a dozen individuals, one of which preserved an almost complete skeleton [5] , which apparently belonged to an immature specimen. The holotype (currently in the collection of the University of Antananarivo ) was represented by a fragment of the left side of the upper jaw with a canine and two incisors , the right side of the lower jaw with a fully preserved set of premolars and molars , as well as two skeleton elements - the middle parts of the humerus and femur [2] .

Babacotius Place

in the taxonomy of the lemur-like [6] [7]

| Lemuriformes |

| Daubentoniidae |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Cheirogaleidae |

|

| Lepilemuridae |

|

|

|

|

| † Archaeolemuridae |

|

| | † Palaeopropithecidae |

| † Mesopropithecus |

|

|

| † Babakotia |

|

|

| † Palaeopropithecus |

|

| † Archaeoindris |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Indriidae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The found remains were immediately identified as the remains of a close relative of the Paleopropithecus [8] (a few years later for the physique of the so-called “sloth lemurs” [3] ) and together with the remains of the Mesopropithecus helped to determine the place of the Paleopropitec lemurs with respect to both modern Indrii and relatively Archeolemurovs - another extinct family. Archeolemurov skulls were similar in appearance to indriy skulls, but they were distinguished by highly specialized teeth, unlike indriyi teeth. On the contrary, babacotia and mesopropithecus related not only the type of the skull to the Indians, but also the structure of the teeth, which made it possible to assert the closeness of the Indri and Paleopropithecus and the more distant kinship of both of them with the archaeological Lemurs [9] (this opinion remained dominant in the future [7] [10] , although in one of the studies of 2008, archaeological Lemurs are considered as closer to the Paleopropitec than the Indriyum [11] ). In addition, the discovered remains helped to establish that the Paleopropithecus did not move, like modern Indians, with quick jumps from branch to branch, but slowly crawled along the trunks and fed like modern sloths , hanging horizontally on the branches, although they probably could have jumped [ 12] .

According to estimates from the end of the first decade of the 21st century, babacotia weighing 12 to 30 kilograms with an average body weight of about 21 kg [13] occupied an intermediate position in the family. They were much smaller than the representatives of two other genera of sloth lemurs - Archeoindri and Paleopropithecus, but larger than the third genus, mesopropithecus [14] .

Skull

Babakotia radofilai Although the skull of all Paleopropithecus skulls is more massive than that of Indri [3] , the skull of babacotia is similar at the same time to the skulls of larger sloth lemurs and to the indri skull. Relatively small eye sockets , powerful zygomatic arches, and an almost rectangular hard palate are typical for paleopropithecus [15] . Orbital ridges or other periorbital thickenings are absent, but there is a powerful postorbital process [16] . Small eye sockets (in absolute size comparable to eye sockets of modern daytime lemurs) and a narrow visual channel indicate low sharpness of vision [17] ; at the same time, the auditory bull is enlarged, the tympanic ring is located inside it [16] . The average length of the skull is 11.4 centimeters [18] .

The chin symphysis in babacotia (as well as in indriy and mesopropitecs) did not overgrow. The dental formula is the same as that of the other Paleopropitec and Indri [3] - 2.1.2.3 1.1.2.3 [19] or 2.1.2.3 2.0.2.3 [20] (the discrepancies in the dental formula are due to the fact that it is not clear whether one of the permanent teeth with a cutter or canine [21] ). In any case, the lower jaw of babacotia (as well as mesopropithecus, but not in archaeoindri and paleopropithecus [14] ) is characterized by a tooth crest of four front teeth, in contrast to the crest of six teeth, more common among wet-nosed monkeys. Unlike indriyas, babakotii had longer elongated premolars (small molars). Their molars are characterized by a wide cutting edge and small notches on the enamel [16] ; cutting coefficient ( English shearing quotient - an indicator of the ratio of the length of the cutting edges to the total length of the molars), generally high in subfossil lemurs, in babacotia has the highest values (up to 50%) [22] . Both molars and premolars are flattened laterally, which is generally typical of indriy and paleopropitec. The crown of the front premolar is characterized by a bulge in the middle part, protruding beyond the neck of the tooth , and the crown of the second premolar is characterized by bilophodontia, that is, by the presence of two transverse ridges connecting the four tubercles of the crown. The central upper incisors are longer than the lateral ones and are separated by a gap. These features are unique to babacotia, distinguishing them from both modern indriyas and well-known paleopropytec ones. The upper palate is elongated and narrow, smoothed in the middle part - the same feature, but even more pronounced, is also characteristic of paleopropites and archaeoindri [23] .

In accordance with the intermediate sizes, the degree of adaptation of babacotia to a hanging lifestyle, similar to that of modern sloths, was also intermediate in comparison with other genera of the family [3] [24] [25] [26] . This genus is characterized by highly mobile joints of the thigh and ankle and a number of other adaptive changes in the spine, pelvis, and limbs [26] . The femoral head is spherical, devoid of a fossa [27] . The hind limbs are generally poorly developed, a number of details, including in the pelvic girdle, are reduced. So, the anterior tibial ankle , the lower ileum , the calcaneus are reduced; the sciatic spine is embryonic. The pubic bone is elongated [16] ; there was a rudimentary tail [28] . The forelimbs of babacotia were almost 20% longer than their hind limbs, so their intermembral index (118 [16] –119) was higher than that of mesopropitecs (from 97 to 113), bringing them closer to sloths and showing that in these two In these cases, convergent evolution [26] [29] could take place. The limbs are characterized by a shortened tarsus and elongated curved phalanges of the fingers, adapted for reliable grip and indicating a hanging lifestyle. This is characteristic of all Paleopropithecus and is not typical of both modern Indrii and another family of fossil lemurs - the archaeolemur , whose proximal (main) phalanges are curved at half the angles than in babacotia. At the same time, sloths, as well as koats and modern lemurs of the vari demonstrate a similar degree of curvature of the phalanges, according to the latest data, also leading a hanging lifestyle [26] [27] . Thumbs on both the front and hind legs are somewhat shortened compared to the rest [16] .

Short hind limbs, characteristic of all paleopithecite ones, were well adapted for climbing and hanging, but not for jumping, which modern indriyas perform [5] . The ratio of the length of the humerus and femur, which amounted to almost 1.2, differs sharply from the ratio in species moving by jumping - in the latter, the femur, on the contrary, is significantly longer than the humerus; even for lemurs, vari, this value is the inverse of the relation described in babacotia. Of modern mammals, the intermembral index, similar to that of babacotia, was recorded in the predominantly hanging lifestyle of two-fingered sloths , as well as in gorillas [30] . Found in 1999, the bones of the wrist joint also indicate adaptability to vertical climbing [31] . An analysis of the semicircular canals [32] and the vertebrae of the lumbar allows us to conclude about the slowness of movements, as well as, in contrast to even more specialized paleopithecines, about adaptation to vertical climbing, as in orangutans or Loria [33] [34] . The large lengths of the feet and palms with respect to the length of the entire limb push the same conclusions. This feature, which is also characteristic of the Paleopropithecus and another fossil of the lemur - megaladapes , is only among orangutans among modern primates [35] . In general, it can be assumed that, like Loriacs, babacotias slowly crawled along the branches and probably spent a lot of time hanging on them like sloths [20] .

Babacotia, extinct relatively recently and known only by subfossil remains, are considered the modern genus of lemurs [3] . Babakotia radofilai , who lived in Madagascar in the Holocene , may have disappeared from the face of the earth after the arrival of people on the island, about a thousand years ago. However, to date, the only known radiocarbon analysis of its remains allows us to attribute them to the period between 2500 and 2300 years BC [36] (babacotia remain the only known subfossil genus of lemurs whose existence after the appearance of a person in Madagascar has not yet been confirmed [37] ).

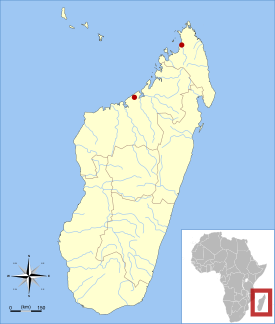

Babacotia, like other lemurs, were endemic to Madagascar. Since their remains, in addition to the Ankaran plateau, were found only in one place, Anjokhib cave, also in the north of the island, but 400 km south of Ankaran [38] , we can conclude that the range of this genus was northern and north- western Madagascar [18] . A small area of distribution even during the period when almost all of Madagascar was covered with forest may be associated with a specific diet, competitive exclusion, or some other unknown reasons [39] . Nevertheless, it was shown that the range of babacotia intersected with the areas of two other species of sloth lemurs - Palaeopropithecus maximus and Mesopropithecus dolichobrachion [4] . Based on body size, structure, and tooth wear, it has been suggested that babacotia were leaf-eating ; their diet also probably included fruits and hard seeds [40] [41] [42] . Small differences in the nature of tooth wear in the genera Babakotia and Palaeopropithecus (a larger number of pits in the enamel in babakotia) are explained by the likely content of stiffer leaves [43] or seeds in the diet [44] .

Based on the available findings, already in 1992 it was suggested that the slow leaf-eating babacotia led a daily life and were noisy, rarely breeding animals [3] . The relatively small brain volume of gigantic extinct lemurs is considered as evidence of low social activity and living in small groups (although the specific details of the micro-wear of the tooth combs indicate that it was used for grooming - combing and brushing fur, it is not known whether this occupation was social in nature [45 ] ). The strong seasonality of the weather in the habitat of sloth lemurs implied a lifestyle and, ultimately, anatomy, coupled with energy conservation and the most efficient use of food resources [46] . In particular, babacotia, as well as other Paleopropithecus and Indrius, is characterized by the early appearance of permanent teeth, which ensured the survival of young individuals in the first dry season after weaning [26] . Based on the peculiarities of tooth development, it is assumed that both weaning and later on achieving puberty occurred, apparently, faster than in monkeys of comparable sizes [47] .

Although there is no definite indication of who was the natural enemy of the babacotia, their remains are found in the same places and in the same layers as the remains of the large crocodile Voay robustus (primarily on the Ankaran plateau). Numerous remains of large subfossil lemurs of other species ( Palaeopropithecus , Archaeolemur , Megaladapis ) with traces of crocodile teeth are known. It is possible that this predator also hunted for babacotia, similar or smaller in size than the listed species, in contrast to the giant fossa Cryptoprocta spelea and large birds of prey, which usually preferred smaller game (in particular, subfossil lemurs Pachylemur were included in the diet of the giant fossa insignis , whose body weight slightly exceeded 10 kg ) [48] .