The Second Battle of Winchester took place on June 13-15, 1863 in Frederick County and near Winchester (Virginia) and was part of the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War . South Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell moved down the Shenandoah Valley towards Pennsylvania , his corps attacked and defeated a federal detachment under the command of Major General Robert Milroy , captured Winchester and took many prisoners.

| Second Battle of Winchester | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Conflict: American Civil War | |||

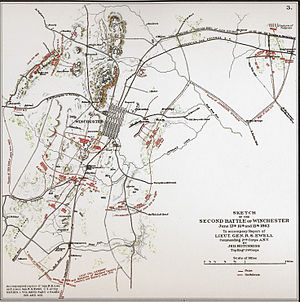

The battle of Winchester , a map of Jedia Hotchkis | |||

| date | June 13-15, 1863 | ||

| A place | Virginia | ||

| Total | KSA victory | ||

| Opponents | |||

| |||

| Commanders | |||

| |||

| Forces of the parties | |||

| |||

| Losses | |||

| |||

Background

After the battle at Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, Confederate General Robert Lee ordered the Second Corps of General Richard Ewell (19,000) from the North Virginian Army to enter the Shenandoah Valley and clear it of the enemy so that the main army could pass through the valley to Pennsylvania. This was Ewell's first assignment as his corps commander. He only at the end of May received the rank of lieutenant general, and on June 1 he was appointed commander of the corps. In 1862, Ewell took part in the first battle of Winchester under the leadership of General Jackson, so he was well aware of the impending task.

The forces of the parties

Confederate Army: Ewell Corps II

- Jubal Airlie Division: Harry Hayes , William Smith , John Gordon, and Isaac Avery Brigades. (5 800 people)

- Robert Rhodes Division: Brigades of Junius Daniel , George Dols , Alfred Iverson , Steven Ramser and Edward O'Neill . (8 500 people)

- Edward Johnson Division: George Stewart Brigades, James Walker ( Stone Wall Brigade ), John Jones and Jesse Williams . (6 900 people) [1]

- Albert Jenkins Cavbrigade

- Colonel Thompson Brown's corps artillery.

Federal Army: 2nd Division VIII Corps

The detachment of Major General Robert Milroy. 6,900 people in three infantry brigades: Washington Elliott, Andrew McReynolds and William Ely. And two small pickets under the command of Colonel Joseph Keifer.

Milroy's defensive measures

By April 1863, the occupation of Winchester lasted four months. Milroy set up pickets and observation posts around Winchester, but they were too close to the city, so Milroy knew practically nothing about what was happening around. He did not place long pickets out of fear of enemy raiders. For example, on February 26th, two of his cavalry regiments (1st New York and 13th Pennsylvania) stumbled upon the 7th and 11th Virginia regiments of Colonel Fansten and scored 197 people, including 12 officers. Milroy also wrote in reports about the destruction of the rangers of Colonel John Mosby , but the reports on Mosby himself do not mention raids on Winchester. As a result, the farthest observation post on the south side of the city was only one mile away.

In Winchester itself, Milroy built or improved about a dozen fortifications called “batteries”. He used the old fortifications built at different times by the federals and confederates. The fortifications were connected by roads and trenches, and all this, together with long-range artillery, allowed Milroy to assume that he could keep Winchester for several weeks, or even months.

During the battle, Milroy deployed his troops on the heights west of the city, in the three largest forts. Namely:

- Battery No. 2 - Fort Milroy : Built originally by the Confederates, it was refined by Banks and named the “Fort Garibaldi”. There were 14 guns in the fort, including heavy ones. After the battle, the southerners renamed the fortification "Fort Jackson." (According to Scott Mingus, there were 6 guns in the fort: 4 20-pound Parrots and 2 24-pound howitzers [2] )

- Baarea No. 3 - Star Fort : built by the feds in 1862 north of the city, reinforced by Milroy. Had 8 guns.

- Battery No. 5 - West Fort : Lunette with 4 light guns, west of Fort Milroy. This lunette was designed for 500 people.

There were several more fortifications, but Milroy hardly used them in battle:

- Battery No. 1: Fortification on Bever Hill, south of the city. Jackson stormed this hill back in the 1862 campaign.

- Seven more unused fortifications.

Later in the report, Milroy points out that there were 4 20-pound Parrots and 2 24-pound howitzers in the fortifications [3] .

Maneuvers

The movement of the Ewell Corps was part of the maneuvers of the entire North Virginia Army , the purpose of which was to transport the army through the Potomac and enter Pennsylvania under the cover of the Blue Ridge Range. The offensive began on June 3. Longstreet 1st Corps and Hill 3rd Corps moved parallel to Ewell's Corps through Burryville , and Stuart's cavalry was supposed to deprive the enemy of information and advance the army and organize false demonstrations.

June 4 - 11

On June 4, the II Corps left Hamilton Crossing and moved to Culpeper , where it arrived on June 7. Upon learning that the feds had crossed the Rappahanock, General Lee ordered Ewell on June 9 to head towards Brandy Station and help General Stuart in the battle at Brandy Station . However, arriving at the site, Ewell discovered that the enemy had already retreated. Then on June 10, Ewell continued to move. On June 11, Earley and Johnson’s divisions headed along the Spurreville Road to the Gaines Crossroads, while the Rhodes Division went along the Richmond Road to Flint Hill. On the evening of the 11th, in consultation with General Lee , Ewell met with Earley, Johnson and the corps surveyor Jedia Hotchkiss, and discussed with them the plan of attack on Winchester and Martinsburg.

June 12th

Ewell’s corps entered the Shenandoah Valley through the Chester Gorge, southeast of the Front Royal and moved along the Front Royal Road. There, the cavalry brigade of Albert Jenkins joined the corps. Ewell conferred with Airlie and Jenkins and came to the next plan.

He decided to divide the case into two parts. The Rhodes division and the Jenkins cavalry were to move to Berryville and Martinsburg and defeat the McReynolds detachment (1,800 men). The main part of the corps, the division of Earley, Johnson and the 16th Virginia cavalry regiment were supposed to go to Winchester to attack its fortifications and destroy the Milroy detachment (6-8 thousand people).

Towards the end of the day, June 12, the Rhodes division was five miles north of Front Royal, the Johnson division came to Cedarville, and the Earley division camped by the Shenandoah River.

Main battle

June 13th

Ewell and his generals well represented Winchester’s position, as they fought here in the first battle of Winchester . Ewell once again divided his forces for two flank maneuvers:

Western Airlie's division, artillery battalion, 1 Maryland battalion and Baltimore light artillery. These forces moved to Newton to reach Winchester from the southwest.

East . Johnson’s Division, 16th Virginia Cavalry. These units moved northwest along the front-royal road, conducting a demonstration on the eastern side of Winchester, diverting attention from the advancement of the Earley division.

Carrying out this plan, Johnson’s division moved along the Fortroyal road, at 08:30 dropped federal pickets off the Opekon River and at 09:30 entered into a shootout near Hodge Run. Johnson's offensive was stopped by the fire of heavy guns with Fort Milra around noon. Meanwhile, Earley’s division, advancing along the Valley-Pike road, reached Kernstown and at about 4:00 pushed north federal pickets.

The battle has already begun, but Milroy did not understand that he was dealing with a whole corps. He gathered all his strength in three forts defending the city. Fearing this kind of action, Commander-in-Chief Henry Halleck had long asked Schenk to give Milroy the order to retreat from Winchester to Harpers-Ferry. Schenk discussed evacuation with Milroy, but he didn’t tell Milroy the evacuation directions, and Milroy convinced Schenk that his defensive positions near Winchester are strong enough. Milroy had decided in advance to ignore the advice from Washington, because he was confident in the strength of his fortifications and believed that he could withstand the attack or siege.

At noon, the Rhodes division reached Berryville and attempted to capture the McReynolds brigade, but he was warned of danger and retreated to Winchester, where his men occupied Star Fort north of the city. Nevertheless, the Confederates managed to seize part of the enemy convoys and 75 prisoners from Bunker Hill. Southerners cut the telegraph wire, thereby destroying Milroy’s only communication line. By the evening of the 13th, the Rhodes division reached Martinsburg, occupied the city and captured five guns. At night, a storm and heavy rain began.

June 14th

At dawn on June 14, the Gordon and Hayes brigade rushed to Bovers Hill and captured him at 09:00 without serious resistance. Airlie and Ewell conferred on Bowers Hill and decided on a flank bypass . Gordon led his men into a distracting attack north of the hill, and at this time the Hayes brigade turned back, connected with the teams of William Smith and Isaac Avery and began a roundabout maneuver. Airlie now had three brigades, approximately 3,600 men, he led them back to Cedar Creek, then westward beyond the ridge of Apple Pie, where the feds could not see him. From there, he turned north, taking with him 20 guns. The brigades had to go 8 miles. They were assisted by local conductor James Baker. While Earley was doing this maneuver, Johnson sent forward a line of shooters to distract the enemy. They started a shootout, which lasted from 10:00 to 16:00. Confederate batteries at Bowers Hill began an artillery duel with federal guns at Fort Milroy.

Meanwhile, Milroy was very afraid of the flank detour and at 10:00 sent a reconnaissance detachment of captain Charles Morgan. Morgan returned at 14:00 and said that the flanks are clean.

Meanwhile, at 4:00 p.m., Earley’s detachments took a mile from the West Fort on the Apple Pie Range. Earley gave people an hour to rest, and then ordered the installation of artillery in position: eight guns were placed at Brierly Farm northwest of the fort, and 12 were installed in the garden southwest of the fort. Milroy at this time decided that the attack was repelled, and did not suspect that he was now completely surrounded and cut off from the main forces.

At about 6 p.m., Earley artillery opened fire on the Western Fort, which was defended by the 110th and parts of the 116th Ohai regiments under the general command of Colonel Keifer. 20 guns fired for about 45 minutes, while Hayes's Louisiana brigade quietly walked through corn and wheat fields at the foot of the ridge. The Smith and Avery brigades walked behind as a reserve. The Louisiana Tigers approached the fort 300 meters and rushed forward on command. After a short hand-to-hand fight, the feds left the fortifications and retreated to Fort Milroy. 79 lost airlie brigades during this attack. Milroy wrote in a report that 10,000 enemy soldiers participated in this attack [4] .

Ewell watched the assault through a telescope, and it seemed to him that he saw Earley in the ranks of the attackers. “Cheers to the Louisiana guys! He shouted. “There is Earley.” I hope the old friend does not suffer [1] . " At this time, a random bullet hit Airlie, but she was already at the end and did not cause serious harm.

Southerners captured six rifled guns, of which two immediately turned towards the enemy. Airlie entrenched at the fort, but darkness did not allow the advance to continue. However, the artillery duel continued after sunset. After the battle, Airlie renamed the fort “Louisiana Heights” in honor of Hayes’s Louisiana Brigade.

Ewell suggested that Milroy would try to retreat at night, so he ordered Johnson to take the three brigades, head north and cut the escape routes north-east along the Charles Town Road. At around 9 p.m., Johnson took the Stuart and Williams brigades and 8 guns and set off along the Berryville road and then to the Stephensons Depot - the Winchester-Potomac railway station - where the Martinsburg road and Charlestown intersected. The third brigade - the brigade of the stone wall - got lost in the dark and went the same way with some delay.

At this time (about 21:00) Milroy gathered a council of war, at which it was decided to break into Harpers Ferry along the old Charles Town Road. All guns were riveted, and their ammunition destroyed. After midnight, the soldiers quietly left the fortifications and gathered on the field between Star Fort and Fort Milra, and from there went along the railway line to the Stephensons Depot. Southerners did not notice this maneuver until the morning.

June 15th

Around (04:00) on June 15, Johnston’s arrows spotted Milroy’s vanguard - the 12th Pennsylvania Regiment - at the intersection of Valley Pike and the old Charles Town Road. The Charles Town Road crossed the railway line, and a bridge was built over the rails. Johnson built his brigades along the Milbern Road, facing east, pushed them forward and stood on the railway line across Old Charles, so that the bridge was in the center of his position.

Johnson deployed two brigades on both sides of the Charles Town Road: the George Stuart brigade on the right and the Louisiana Tigers on the left, totaling 1,200. Two guns were installed in the center, on the bridge. The feds launched several frontal attacks, but all were repelled. Then they decided to go around both flanks of Johnson, but on the right flank they met the “stone wall brigade” that had just approached, and on the left — the Nichols reserve brigade. Then the feds raised the white flag, 2300 or 2500 people surrendered. The rest rushed into the fields and forests, where they were partially overtaken and captured by the cavalry. General Milroy, with headquarters and three hundred cavalrymen, managed to break into Harpers Ferry.

Consequences

Reports of officers of the North and South call about the same loss figures. Ewell wrote:

The fruits of this victory were 23 artillery barrels (almost all rifled), 4,000 prisoners, 300 loaded wagons, more than 300 horses and many other equipment. We lost 47 people killed, 219 wounded and 3 lost, total 269. Lieutenant Colonel Andrews, who correctly and efficiently managed artillery on the 15th, was wounded at the very end of the battle [5] .

The mentioned number of prisoners includes, apparently, the wounded federal soldiers left in the city, since Ewell’s topographer, Jedia Hotchkis, mentions 2,000 prisoners in the city itself. According to northerners, the losses were as follows: 7 officers were killed, 88 privates; 12 officers were injured, 336 privates; 144 officers were captured, 3856 privates. Only one division of Johnson captured 3,500 people in the battle at the Sensensons Depot.

Milroy with his headquarters and part of his soldiers, only 1,200 people, broke into Harpers Ferry. The 2nd division of the VIIIth Corps practically ceased to exist. Milroy was placed under arrest and put on trial. Both Lincoln and Halleck were interested in the question: who exactly did not comply with the order to evacuate Winchester. Milroy was eventually acquitted, but never received a new appointment.

In his report, Milroy shifted responsibility to the Potomac Army, which allowed “at least two Lee Army corps” of 50,000 people to attack and surround Winchester. "The precedents of this war justify surrender" [6] , wrote Milroy, but, in his opinion, his life belongs to the government, so he decided to fight his way through. He also cited a shortage of food and ammunition.

The battle of Winchester was the first battle of the Gettysburg Campaign (apart from the unplanned clash at Brandy Station ), it cleared the North Virginian army's path through the Shenandoah Valley and opened the way for an invasion to the north. The captured prey justified Lee’s calculations that the army could be supplied at the expense of the enemy. Ewell’s corps continued to move north: already in the evening of June 15, General Rhodes with three brigades crossed the Potomac at Williamsport.

In General Ewell's career, the battle was the first experience in managing the corps, and he proved that he could cope with such tasks. “With one powerful blow, Ewell destroyed the enemy in the Shenandoah Valley, cleared the way for the invasion of the north, and eliminated Milroy’s division as a combat unit until the very end of the war. But most importantly, Ewell’s impressive victory gave the South hope that there was a man who could replace General Jackson. A new star flashed in the sky of the Confederation ” [1] . The historian Donald Pfantz wrote that the second Winchester was the climax of Ewell's military career. “Skillfully planned and faultlessly implemented, this operation was brilliant in every way,” he wrote. Ewell’s quick maneuvers and swift attacks resembled Jackson’s tactics to many, and one northerner said that the southerners probably lie about Jackson’s death, “... since there isn’t an officer in our armies who could carry out such maneuvers except for Old Jack.” Major Henry McKid Douglas called Ewell's tactics "Jacksonian." Such assessments formed in the South high expectations and reevaluation of Ewell, and in this sense, according to Pfants, Ewell’s greatest victory ultimately became his greatest misfortune [7] .

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 3 Second Battle of Winchester: Richard Ewell Takes Command

- ↑ Scott L. Mingus, The Louisiana Tigers in the Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863, LSU Press, 2009 p. 23

- ↑ Milroy Report

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records

- ↑ Report of Lieut. Gen. Richard S. Ewell

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records

- ↑ Pfanz, 1998 , p. 290

Literature

- Beach, William H. The First New York (Lincoln) Cavalry: From April 19, 1861 to July 7, 1865. New York: The Lincoln Cavalry Association, 1902.

- Grunder, Charles S. and Beck, Brandon H. The Second Battle of Winchester (2nd Edition). Lynchburg, VA: HE Howard, Inc., 1989. ISBN 0-930919-90-4

- Grunder, Charles S. and Beck, Brandon H. The Three Battles of Winchester: A History and Guided Tour (2nd Edition). Berryville, VA: The Civil War Foundation, Inc., 1997. ISBN 0-939685-07-8

- Maier, Larry B. Gateway to Gettysburg: The Second Battle of Winchester. Burd Street Press: Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, 2002. ISBN 1-57249-287-2

- Early, Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States. With Notes by RH Early. Philadelphia: JP Lippincott Company, 1912.

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84944-5 .

- Hotchkiss, Jedediah, (McDonald, Archie, Ed.) Make Me a Map Of the Valley: The Civil War Journal of Stonewall Jackson's Topographer, Southern Methodist University Press, Dallas, 1973. ISBN 0-87074-270-1

- Kennedy, Frances H., Ed., The Civil War Battlefield Guide , 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998, ISBN 0-395-74012-6 .

- Pfanz, Donald C. Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier's Life. - Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998 .-- 655 p. - ISBN 978-0-8078-2389-7 .