The category theory is a branch of mathematics that studies the properties of relations between mathematical objects that are independent of the internal structure of objects.

Category theory occupies a central place in modern mathematics [1] , it has also found applications in computer science [2] , logic [3] and in theoretical physics [4] [5] [ specify ] . The modern presentation of algebraic geometry and homological algebra is essentially based on the concepts of category theory. General category concepts are also actively used in the functional programming language Haskell [6] .

Definition

Category - this:

- feature class

;

- for each pair of objects

,

many morphisms (or arrows) are given

, and each morphism corresponds to the only

and

;

- for a couple of morphisms {\ displaystyle f \ in \ mathrm {Hom} (A, B)}

and

defined composition

;

- for each object

given morphism

;

moreover, two axioms are fulfilled :

- composition operation is associative :

and

- the identical morphism acts trivially:

for

Small category

A class of objects is usually not a set in the sense of the axiomatic set theory . Category C in which is a multitude and

(the set of all morphisms of a category) is a set, called small . In addition, it is possible (with a slight correction of the definition) to consider categories in which morphisms between any two objects also form a class, or even a large structure [7] . In this version of the definition, a category in which morphisms between two fixed objects form a set is called locally small .

Category Examples

- Set is the category of sets . Objects in this category are sets , morphisms are maps of sets.

- Grp is a category of groups . The objects are groups, morphisms are mappings that preserve the group structure (group homomorphisms ).

- Vect K is the category of vector spaces over the field K. Morphisms are linear mappings .

- Category of modules .

Similarly defined categories for other algebraic systems .

- Top is a category of topological spaces . Morphisms are continuous mappings .

- For any partially ordered set, one can construct a small category whose objects are the elements of the set , and there exists a unique morphism between the elements x and y if and only if x ≤ y (of course, this category should be distinguished from the category of partially ordered sets!).

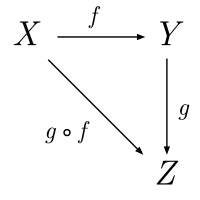

Commutative Diagrams

Commutative diagrams are the standard way to describe statements of category theory. A commutative diagram is a directed graph whose vertices contain objects and the arrows are morphisms, and the result of the composition of the arrows does not depend on the chosen path. For example, the axioms of category theory (composition associativity and the property of identical morphism) can be written using diagrams:

Duality

For category a dual category can be defined , wherein:

- objects coincide with the objects of the original category;

- morphisms are obtained by "reversal of the arrows":

The principle of duality says that for any statement of category theory it is possible to formulate a dual statement using the inverse of arrows, while the truth of the statement will not change. Often, a dual concept is denoted by the same term with the prefix co- (see examples below).

Basic definitions and properties

Isomorphism, Endomorphism, Automorphism

Morphism is called an isomorphism if there is such a morphism , what and . Two objects between which there is an isomorphism are called isomorphic . In particular, the identity morphism is an isomorphism; therefore, any object is isomorphic to itself.

Morphisms in which the beginning and end coincide are called endomorphisms . Many endomorphisms is a monoid with respect to the operation of a composition with a single element .

Endomorphisms, which are simultaneously isomorphisms, are called automorphisms . Automorphisms of any object form a group of automorphisms by composition.

Monomorphism, epimorphism, bimorphism

Monomorphism is morphism such that for any of follows that . The composition of monomorphisms is a monomorphism.

Epimorphism is such a morphism for any of should . The composition of epimorphisms is epimorphism.

Bimorphism is a morphism that is both a monomorphism and an epimorphism. Any isomorphism is a bimorphism, but not every bimorphism is an isomorphism.

Monomorphism, epimorphism, and bimorphism are generalizations of the concepts of injective , surjective, and bijective mapping, respectively. Any isomorphism is a monomorphism and an epimorphism; the converse, generally speaking, is not true for all categories.

Initial and terminal objects

An initial (initial, universally repulsive) category object is an object from which a single morphism exists in any category object.

If the initial objects in the category exist, then all of them are isomorphic.

A terminal or universally attractive object is defined in a dual way - it is such an object into which from any object of the category there is a single morphism.

A category object is called null if it is both initial and terminal.

- Example: In the category Set, the initial object is an empty set. , terminal - any set of one element .

- Example: In the Grp category, there is a null object - this is a group of one element.

The product and the amount of objects

The product (pairs) of objects A and B is an object with morphisms and such that for any object with morphisms and there is only one morphism such that the diagram shown on the right is commutative. Morphisms and called projections .

Doubly determined by the amount or coproduct objects and . Corresponding Morphisms and called attachments . Despite their name, in the general case, they may not be monomorphisms .

If a product and coproduct exist, then they are uniquely determined up to isomorphism.

- Example: In the category Set, the product of A and B is a direct product in the sense of set theory , and the sum is a disjoint union .

- Example: In the Ring category, a sum is a tensor product. and the product is the direct sum of the rings .

- Example: In the category Vect K (finite), the product and the sum are isomorphic - this is a direct sum of vector spaces .

- Example: In the Ring category, a sum is a tensor product. and the product is the direct sum of the rings .

It is easy to define in a similar way the product of any family of objects . Infinite products are generally more complicated than finite ones. For example, while finite products and coproducts in Vect K are isomorphic to direct sums, infinite products and coproducts are not isomorphic. Elements of an endless work. are arbitrary infinite sequences of elements while elements of infinite coproduct are sequences in which only a finite number of members are nonzero.

Functors

Functors are category mappings that preserve the structure. More precisely,

(Covariant) functor associates each object with a category category object and to every morphism morphism so that

- and

- .

A contravariant functor , or co- functor , can be understood as a covariant functor from at (or from at ), that is, a functor that turns arrows. Namely, to each morphism he juxtaposes morphism , the composition rule is accordingly addressed: .

Natural Transformation

The concept of natural transformation expresses the relationship between two functors. Functors often describe “natural constructions”, in this sense, natural transformations describe the “natural morphisms” of such constructions.

If a and - covariant functors from the category at then the natural transformation matches each object categories morphism such that for any morphism in category the following diagram is commutative:

Two functors are called naturally isomorphic if there is a natural transformation between them such that Is an isomorphism for any .

Some types of categories

- Monoidal Categories

- Abelian categories

- Toposs

See also

- Baire Category

- Universal property

- Limit

- Adjoint functors

- Monads

Links

- ↑ Khelemsky A. Ya. Lectures on functional analysis. - M .: MCCMO, 2004 ISBN 5-94057-065-8

- ↑ DE Rydeheard, RM Burstall Computational Category Theory, - New York: Prentice Hall. - 1988. - XIII, 257 p. - ISBN 0-13-162736-8 .

- ↑ R. Goldblatt. Toposs. Category analysis of logic = Topoi. The categorial analysis of logic. - M .: Mir , 1983 .-- 488 p.

- ↑ Do physicists need category theory? . Original http://arxiv.org/abs/0808.1032

- ↑ Topos Archived December 5, 2008 on the Wayback Machine for Physics. (eng.)

- ↑ Category theory in Haskell . Date of treatment March 13, 2011. Archived on August 24, 2011.

- ↑ J. Adámek, H. Herrlich, GE Strecker Abstract and concrete categories: The joy of cats , - New York: John Wiley and Sons, - 1990.

Literature

- S. Mac Lane [Maclane S.] Categories for a working mathematician. - M .: Fizmatlit, 2004 [1998].

- S. Mac Lane [Maclane S.] Homology. - M .: World - volume 114 of the Springer-Verlag series - Grundlehren der mathematischen wissenschaften , 1966 [1963].

- Tsalenko M.S., Schulgeifer E.G. Categories. - volume 06 series - VINITI - Results of science and technology, Algebra-Topology-Geometry`, 1969.

- Tsalenko M.S., Schulgeifer E.G. Lectures on category theory. - M .: Science , 1970.

- Tsalenko M.S., Schulgeifer E.G. Fundamentals of category theory. - M .: Science , 1974.

- Bukur I., Delyanu A. Introduction to the theory of categories and functors. M .: Mir, 1972. 259 p.

- Face [Faith C.] Algebra - rings, modules and categories, volume 1. - M .: World - volume 190 of the Springer-Verlag series - Grundlehren der mathematischen wissenschaften - 1977 [1973].

- Face [Faith C.] Algebra - rings, modules and categories, volume 2. - M .: World - volume 191 of the Springer-Verlag series - Grundlehren der mathematischen wissenschaften - 1977 [1976].

- Gabriel [Gabriel P.], Cisman [Zisman M.] Categories of quotients and theory of homotopy. - M .: World - Volume 35 of the Springer-Verlag Series - Ergebnisse der mathematik und ihrer grenzgebiete - 1971 [1967].

- Goldblatt [Goldblatt R.] Topos - categorical analysis of logic. - vol. 98 of the series Studies in logic & foundation of mathematics - 1983 [1979].

- Fulton E, McPherson R. A categorical approach to the study of spaces with singularities. - Volume 33 Series New in Foreign Science, Mathematics - Ed. Buchstaber V.M. - 1983.

- Artamonov V.A., Saliy V.N., Skornyakov L.A., Shevrin L.N., Shulgeifer E.G. General algebra. Volume 2. - M., Science, 1991. - 480 p. - ISBN 5-02-014427-4 . - Circulation 25500 copies.