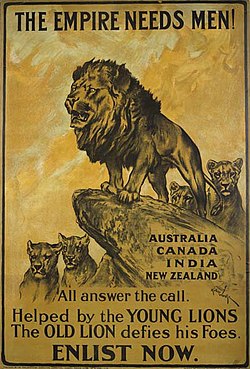

“Empires need men!

Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand

Everyone respond to the call.

Supported by young lions, the old lion challenges his enemies.

Sign up for the service today. ”

Great Britain passed the First World War as a part of the military-political bloc of the Entente ; continuously developing, the country achieved its goal, defeating the bloc of the Central Powers ( German Empire , Austria-Hungary , the Ottoman Empire and the Bulgarian kingdom ). During the war, the British Armed Forces underwent a major reorganization, for example, the Royal Air Force was created ; the number of troops has increased. For the first time in the history of the country , a forced call was made [1] . With the outbreak of war, patriotic feelings swept the whole country, social barriers between the social classes of Edwardian England decreased during this period [2] .

To achieve victory over the enemy had to make significant sacrifices. In order to prevent shortages of labor and food shortages, the government has developed a number of laws, such as the Kingdom Protection Act , giving itself additional powers to ensure the safety of its citizens. During the war, a change in the attitude of the authorities towards it took place. The primary policy of “business as usual” [3] and the preservation of the pre-war status quo under Herbert’s office of Henry Asquith [4] had to be abandoned in favor of a total war regime (state influence on all spheres of public life) under Prime Minister David Lloyd George [5] that was first observed in Britain. British cities first became targets of aerial bombardment .

The morale in society was maintained at a fairly high level, largely thanks to the media ; newspapers flourished in wartime [6] . Government propaganda has been successfully planted, thanks to the work of journalists such as Charles Masterman and newspaper publishers like Lord Beaverbrook . By adapting to demographic changes in the workforce, war-related industries grew rapidly, and production increased due to the hiring of a large number of people [7] . In addition, the first massive use of female labor began, which forced the parliament to pass a law in 1918, which granted a significant number of women the right to vote [8] .

During the war, the British royal family , led by George V, broke off ties with their German relatives and changed the German name of their dynasty - Saxe-Coburg-Gotha - to Windsor . The problems experienced by the country during the war became an obstacle to saving the royal relatives in Russia, including Nicholas II . Due to food shortages and the “ Spanish ” epidemic that struck the country in 1918, the mortality rate increased [9] . Military casualties exceeded 850,000 people [10] . It is also believed that the war increased the growth of national identity in Canada and Australia , which ended, ultimately, with the collapse of the British Empire . So, both Australia and Canada already then preferred to use national symbols on the battlefields. However, from a geographical point of view, the empire reached its peak as a result of the signing of peace treaties [11] .

Government

(circa 1915)

Great Britain, led by Herbert Henry Asquith , Prime Minister of the Liberal Party , entered World War I at 11 p.m. on August 4, 1914 . In response to German demands for Belgium to allow troops free access to French territory , and after the British ultimatum ended, Asquith declared war on the German Empire [12] . The reasons for declaring war were complex. Under the London Treaty of 1839, the United Kingdom acted as a guarantor of Belgium's neutrality and independence in the event of an invasion, although the Ministry of Foreign Affairs concluded that these obligations might not be fulfilled. Another reason was a “moral duty” to France - large-scale secret negotiations between the countries lasted from 1905, although most of the members of Asquith’s cabinet were not dedicated to them until 1911 . The lack of evidence that war is inevitable led to disagreement within the cabinet even on July 31 [12] .

By the beginning of the war, the political course of the British government, formulated by the ruling party, was against government intervention in private business, which corresponded to the historical position of liberals as advocates of the principles of government non-interference [4] . The policy “business as usual” , as Winston Churchill described it in November 1914 , had to be changed during the war [4] . In May 1915, Asquith’s cabinet was forced to resign due to the crisis in the production of artillery shells and the failure of the Gallipoli campaign on the Dardanelles [13] . Not wanting to go to early elections, May 25 Asquith reluctantly agreed to form a new coalition government, consisting of representatives of his Liberal Party and conservatives [13] .

(approximately in 1920)

This coalition remained in power until 1916, when conservatives became disillusioned with Asquith and liberal behavior, especially because of the Battle of the Somme . The government broke up as a result of the political maneuvers of Andrew Bonar Lowe (leader of the Conservatives), Sir Edward Carson (leader of the Ulster Unionists ) and David Lloyd George (then Minister of War of the Government). Low did not have enough support outside his party to create a new coalition. [13] On the other hand, liberal David Lloyd George, who had far more supporters, was able to properly form a new coalition government. After becoming prime minister, Lloyd George assembled a cabinet in which there were even more conservative representatives than members of his own party [13] . In the first 235 days of its existence, this wartime cabinet met 200 times [5] . Although it consisted of a significantly smaller number of ministers than in the Asquith government, the Lloyd George cabinet was organized in such a way as to be fully responsible for the course of the war [5] . Its creation marked the transition of government policy to a state of total war - in which every man, woman or child must fulfill their role, helping the front. Moreover, according to the law on the protection of the kingdom , it was decided to concentrate all the levers of managing military-economic activity under government control [5] . For the first time, the government could respond to events promptly, without an endless bureaucratic apparatus that fetters its actions, possessing modern comprehensive statistics, including the state of the merchant fleet and agriculture [5] . The success of the Lloyd George government, among other things, is due to the reluctance to hold elections and the practical absence of dissent [13] .

After the war , the People's Representation Act of 1918 granted voting rights to a much wider segment of the public: all adult married men over 21 years old and all married women over 30 years old [14] . Ultimately, this contributed to the collapse of the liberals and the rise of the Labor Party in the 1920s [2] . This became evident in the general elections of 1918, when the rating of Laborites sharply increased from 6.4% in 1910 to more than 20%, due to the separation of the votes of liberals between supporters and opponents of the continuation of the coalition government [15] .

Monarchy

(cartoon in Punch Magazine 1917)

During the First World War, the British Royal House faced a serious problem due to blood ties with the ruling family of the German Empire - the main enemy of Great Britain in the war. Before the war, the British royal family was known as the Saxe-Coburg-Goth Dynasty . In 1910, after the death of his father Edward VII , George V, who ruled throughout the war, ascended the throne. His cousin was the German Kaiser Wilhelm II , who embodied all the horrors of war for British society. Queen Mary is the daughter of a British woman and Prince Teksky, a descendant of the Royal Württemberg House . During the war, Herbert Wells wrote about the royal family: “an alien and not inspiring court” , to which George V replied: “I can not inspire, but damn me if I'm a stranger” [16] .

Meeting the wishes of his patriotic subjects, George V issued a special law on July 17, 1917, according to which the British royal family became known as Windsor instead of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha . He changed his surname to Windsor to all descendants of Queen Victoria who lived at that time in Great Britain, with the exception of women who were married to representatives of other surnames and their descendants [17] . The king and his relatives - British subjects renounced all German titles and adopted English surnames. Georg, in compensation, made some of his male relatives British peers . So, his cousin Prince Ludwig Alexander Battenberg overnight became Louis Alexander Mountbatten, 1st Marquis of Milford Haven, and his brother-in-law, Duke of Teksky, Adolf Cambridge, 1st Marquis of Cambridge. Others, for example, Princess Maria Louise of Schleswig-Holstein and Princess Elena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein , simply stopped using their territorial designations. The title system of members of the royal family has also been simplified [18] . Members of the British royal family who fought on the side of Germany were expelled from the family; their membership in the British peers was suspended in 1919 by a government decree, in accordance with the terms of the title abolition law of 1917 [19] .

The development of the situation in Russia added to the problems of the British monarchy. Tsar Nicholas II was a cousin to George V, their mothers were sisters, and both monarchs were alike. When, after the February Revolution of 1917, Nicholas II abdicated, the British government prepared to provide asylum to the king and his family. However, the deteriorating living conditions of the population and the fear that the revolution could come to the British Isles , led George V to the idea that the presence of the Romanovs in Britain would be negatively perceived by society [20] . The documents of the king’s personal secretary, Lord Stamfordham, indicate that George V was against granting asylum to the Romanovs, although Prime Minister Lloyd George advised doing so [21] .

By the beginning of the war, the future Edward VIII , then Prince of Wales , had reached the minimum age for participating in hostilities and longed to go to war [22] [23] . He entered the service in June 1914 in the Guards Grenadier Regiment . Although Edward was eager for the front, Secretary of State Lord Kitchener refused to send him there, referring to the irreparable loss that the kingdom would suffer if the heir to the throne were captured [24] . Despite this, Edward saw the trench war with his own eyes and tried to appear at the front as often as possible. For this, in 1916 he was awarded the Military Cross . His, albeit small, role in the war made Edward popular among World War I veterans [25] [26] .

Prince Albert , at that time the Duke of York , and in the future King George VI, was sent to serve as midshipman on the Royal Navy on September 15, 1913, and a year later took part in the First World War. As a tower officer on the Collingwood dreadnought , he fought against the German fleet in the Battle of Jutland , but then did not take part in hostilities, mostly for health reasons [27] .

Princess Maria Windsor , the only daughter of the king, visited the hospitals and social institutions with her mother, assisting in projects to support the British military and help their families. One of these projects was the Princess's Christmas Gift Fund, with which gifts were sent to all British soldiers and sailors for Christmas 1914 for a total of £ 162,000 [28] . Maria took an active part in popularizing the Girl Scout movement ( Girl Guide ), Voluntary Aid Detachment ( VAD ), and the Women's Land Army . In 1918, she graduated from nursing courses and began working at Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Kingdom Protection Act

The Kingdom Protection Act was passed on August 8, 1914, in the early days of the war [29] , but its provisions expanded over the following months [30] . The law gave broad powers to the British government [30] , for example, the possibility of requisitioning buildings and land necessary for military purposes [31] . During the war, British citizens, among other things, were forbidden to stay unreasonably under railway bridges, take photographs or sketch objects of military significance [32] , feed wild animals [33] and discuss military and naval topics [32] . British Daylight Saving Time was also introduced [34] . Alcoholic beverages had to be diluted, the closing time of the pubs moved from 00:30 at 10:00. Since August 1916 in London it was forbidden to whistle cabs from 10 pm to 7 am [34] . Such measures were criticized both for their severity and for the use of the death penalty as a measure of intimidation [35] - although the listed acts themselves were not punishable by death, according to the provisions of the law, violators were transferred to a military tribunal, which had the right to sentence to death [36] .

Manifestation of anti-German sentiments

The British poster reads:

“Once a German is always German!

Remember!

Every employed German is an unemployed Briton.

Any purchased German product is an unsold British product. ”

According to the 1911 census, 53,323 people of German nationality lived in Britain [37] . Over half of them - more than 27 thousand - lived in the capital and its environs [38] .

As the conflict escalated, British attitudes toward local Germans became increasingly hostile [39] . Such sentiments were fueled and fueled by state propaganda bodies. On August 5, 1914, the day after the declaration of war, a law on restrictions on foreigners entered the House of Commons, which forbade foreigners of hostile powers from entering and leaving the country without special permission. All Germans who were in Britain at that time should immediately be registered with the nearest police station [40] .

The list of restrictions for these ethnic groups also included a ban on the possession or storage of firearms , photo equipment, communications, including pigeons [41] . The following regulations against Germany were a group of laws on trade with hostile states , which were issued throughout the war and tightened the position of representations of German enterprises and enterprises of British Germans. The most stringent regulation of this series was the law of January 27, 1916. According to him, the expert commission of the Ministry of Commerce was vested with the right to decide on the liquidation of enterprises, and confiscate their property. By March 1918, the commission had examined 960 cases; in 507 cases, it was decided to close the organizations. This applied both to the British branches of large corporations (for example, Siemens ) with multi-million turnover, and small sewing workshops [42] .

Along with the above actions, the British legislative system actively pursued a policy of internment and deportation of the German population. In the first months of the war, the authorities had not yet developed a definite plan of action for persons subject to imprisonment or expulsion from the country. Nationals of enemy states and their own citizens of unreliable nationalities were either arrested or released again. It was believed that men of draft age were subject to unconditional imprisonment in the camps, all the rest were threatened with deportation.

On May 7, 1915, British society stirred the news of the sinking of the German submarine of the Lusitania passenger liner. The streets of London were filled with thousands of demonstrators calling for the general internment of the Germans. Finally, on May 13, Prime Minister Asquith informed the House of Commons about the forced relocation of all men of military age from 17 to 55 to the camps. German women were expected to be deported. Persons of German nationality, born in the UK, remained at large, but only as long as they did not violate public order.

Thus, by November 1915, the total number of internees was 32,440 people (including the Austrians ). In the summer of 1916, 22 thousand internees were released. Of these, 10 thousand were women, the rest were elderly people, who had lived in the United Kingdom for a long time and were unfit for military service. Between May 1915 and June 1916, about ten thousand returnees , men of non-conscript age, women and children left the country. Many left voluntarily. Of the number of internees, only 6,840 people were able to leave the UK by the end of the war.

The internment camps were located mainly in coastal cities such as Ryde , Gosport and Southend . The London camp was located at Alexandra Palace and the surrounding park. Up to 3 thousand British Germans and subjects of hostile powers were simultaneously in it. The largest place of concentration of internees was the Isle of Man , which contained about 23 thousand people. By the time the armistice was signed, there were 24,255 prisoners in British camps. In total, the British German community, which before the war numbered about 57 thousand people, decreased by 1919 to 22,254 [43] .

However, the most formidable manifestations of anti-German sentiment in British society were riots . The most significant outbreaks of violence occurred in August and October 1914, in May 1915, in June 1916 and in July 1917. The first August spontaneous outbreak of violence resulted in attacks on German-owned stores in east London. In October 1914, riots swept the southern outskirts of the capital and the Deptford area, where eight hundred Belgian refugees had recently arrived.

The largest wave of atrocities swept through the country in May 1915 in response to the sinking of the Lusitania liner. The riots, which were attended by many thousands of participants, began on May 8 in Liverpool and lasted three days. More than five hundred stores were destroyed, the total damage amounted to at least 40 thousand pounds . The unrest, which took on a national character, continued in Manchester , Newcastle , Sheffield , Rotherham and many other cities in Britain. The most devastating pogroms occurred in London, where about two thousand objects of private property were damaged or destroyed, totaling about £ 200,000. 866 people were arrested.

After the riots of May 1915, subsequent outbreaks of violence were less significant. Most German stores were already crushed, and a very small number of ethnic Germans remained at large. The June riot of 1916 was a reaction to the death of the popular Secretary of War Lord Kitchener . His sudden death caused numerous conspiracy theories . And finally, the last surge of protests followed in the London suburbs after an air raid in July 1917, which killed 57 people and injured 193 [44] .

One of the most exotic manifestations of Germanophobia was the official renaming by the largest British cynological organization Kennel Club of the German Shepherd breed to the East European Shepherd or Alsatian Shepherd (from the point of view of the British, Alsace was part of France) [45] . Restoration of the original name of the breed in Britain took place only in 1977 [46] .

British Armed Forces

British Army

Compared to the armies of the remaining major European powers, the British army during the First World War was small. By 1914, Britain had a modest armed forces consisting of 400,000 volunteer soldiers, mostly urban dwellers [47] [48] . Almost half of them carried garrison service outside the British Isles, in garrisons located in all parts of the British Empire. In August 1914, 74 of the 157 infantry battalions and 12 of the 31 cavalry regiments were stationed abroad [1] . This figure included the Regular Army and the reservists of the Territorial Forces [1] . From these troops was formed the British Expeditionary Force [49] , which was sent to France and whose soldiers were nicknamed "Despicable old people . " It is believed that this nickname was given to them by William II in an order dated August 19, 1914: "to exterminate ... the treacherous English and easily defeat the despicable little army of General French . " Volunteers who went to war in 1914-1915 were called the " Kitchener Army." They were destined to join the battle in the Battle of the Somme [1] . In January 1916, universal military service was introduced, and by the end of 1918 the army reached a maximum size of 4 million people [1] .

Royal Navy

At the beginning of the war, the Royal Navy was the largest in the world, mainly due to the Law on Naval Defense of 1889 and the principle of "bipartite standard." This principle meant that the naval forces of Great Britain should be equal to the total power of the two largest fleets of the world following it (they were the fleets of France and tsarist Russia at the end of the 19th century) [50] [51] .

The main forces of the Royal Navy, known as the Grand Fleet , were concentrated in the metropolis. Their main task was to confront the German High Seas Fleet . But in none of the clashes, the most significant of which was the Battle of Jutland , a decisive advantage was not achieved [52] . In the battle of Jutland, despite the significant advantage of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet escaped complete defeat. Despite the fact that the Grand Fleet suffered heavy losses in the battle, the dominance of the British fleet in the North Sea remained, and the German fleet no longer tried to conduct large-scale operations in the future. The lessons of Jutland allowed the Royal Navy to increase its combat capability in the future [53] [54] .

In addition, in 1914, the 63rd (royal naval) division was created on the basis of the fleet. She was manned by reservists and fought on the Western and Mediterranean fronts [52] . Almost half of all the losses of the Royal Navy in the First World War occurred in this division, which fought on land and not at sea [52] .

Royal Flight Corps

With the outbreak of war, the Royal Flight Corps under the command of David Henderson was transferred to France, where at first, from September 1914, he was engaged in air reconnaissance. Reconnaissance became effective with the introduction of wireless communications on aircraft of the corps, which first appeared on May 9, 1915, during the second battle of Artois . The first attempts at aerial photography have been undertaken since 1914, but it has become really useful since the next year.

In 1915, Hugh Trenchard replaced Henderson as commander in chief of the Royal Flight Corps. With his arrival, the corps switched to more active actions. By 1918, photographs could be taken from a height of 15,000 feet (4,600 meters); 3,000 specialists were involved in decoding them. Although parachutes were used before the war, until 1918 aircraft were not equipped with them [55] .

On August 17, 1917, General Jan Smuts submitted a report to the military council assessing the future of the air force. Seeing the task of the new type of troops in the "devastation of enemy territories and the large-scale destruction of industrial centers and densely populated areas" , he recommended developing the country's air force to the level of the army and navy. The British Air Force was to be handed over personnel and equipment of the Royal Naval Air Service ( RNAS ), operating on the Western Front.

The existence of two different air services often led to internal disputes over the distribution of aircraft. On April 1, 1918, the Royal Flight Corps and the Royal Naval Aviation Service were consolidated into a single structure - the Royal Air Force of Great Britain [56] .

Recruitment and Mobilization

For various reasons, at the first stages of the war, many people decided to volunteer to join the ranks of the armed forces of the empire, so, on September 5, 1914 their number exceeded 225,000 people [57] . As combat operations developed, many factors influenced the quantitative indicators of recruitment, for example, the activities of the parliamentary recruitment committee, which distributed campaign posters; reduced job opportunities and even the desire of some to escape everyday routine [57] . Especially popular were the so-called " friendly battalions ”, consisting of residents of one region (for example, the battalion of Glasgow Tram Corporation) [58] . The greatest activity at recruiting stations was observed in Scotland and Wales , in turn, however, periodic political tensions in Ireland and Wales adversely affected recruitment rates [57] .

The recruitment process for recruits and reservists proceeded fairly stably in 1914 and early 1915, but fell sharply in subsequent years, especially after the Somme campaign , which killed 500,000 people. In this regard, in January 1916 a universal appeal was announced, to which single men were subject, and since May all men from 18 to 41 years old in general [59] . The law on military service in the wordings of January and June 1916 defined this age group and category of the population as subject to compulsory appeal [57] . In fact, the needs of many industries and agriculture imposed a limitation on conscription in the form of so-called “reserve professions”. In addition, the law did not apply to Ireland , although it was part of the United Kingdom [57] .

The Call of Crisis of 1918

In April 1918, a new bill was introduced in the British Parliament , proposing the implementation of conscription in Ireland [57] . Although it was never implemented, the effect of its publication was catastrophic [57] . Despite the fact that by that time a significant number of volunteer regiments had been created in Ireland [57] , the prospect of forced mobilization generated an explosion of public indignation. An additional irritation was caused by the fact that the introduction of military service was contrary to the provisions of Gomrul - the law on Irish self-government. Этот конфликт интересов вызвал возмущение ирландских партий в британском парламенте , они покинули Вестминстер и вернулись на родину для организации акций протеста. 23 апреля 1918 года началась всеобщая забастовка, прекратили работу железные дороги, порты, фабрики, верфи, мельницы, трамвайные депо, театры, предприятия коммунального хозяйства, газеты, магазины и даже государственные оборонные предприятия. Такая реакция впоследствии привела к полному неприятию Гомруля и росту популярности националистической Ирландской партии . На декабрьских выборах в Ирландии победила ещё более радикальная партия Шинн Фейн и вскоре началась война за независимость .

Отказники

Воинская повинность предоставляла право отказаться от службы в армии по морально-этическим соображениям и поступить в качестве альтернативы на гражданскую службу, либо служить в армии на должности, не связанной с участием в боевых действиях. Для этого необходимо было представить Военному трибуналу веские доводы о причинах своего отказа. Всего было зарегистрировано около 16 500 человек [57] , по большей части из числа квакеров и традиционных пацифистов. 4500 отказников отправились на фермы, где занимались работой национального значения. Ещё 7000 стали носильщиками носилок в армии, где многие отказались подчиняться приказам и были приговорены к тюремному заключению. Всего 6312 отказников было арестовано, 5970 из них было осуждено на различные сроки заключения [60] . 843 человека провели в тюрьме более двух лет, 10 из них скончались в заключении, 17 человек было приговорено к смертной казни (позднее заменённой на пожизненное заключение), 142 отказника получили пожизненный тюремный срок [61] . Кроме того, лица, отказавшиеся от службы в армии и не выполнявшие другие работы, были лишены гражданских прав в течение пяти лет после окончания войны [62] .

Морские и воздушные рейды

Впервые со времён Наполеоновских войн населению Соединённого Королевства угрожали атаки с моря. Появилась и новая угроза — атаки с воздуха, с цеппелинов и самолётов , [63] [64] .

Рейд на Ярмут

«Помни о Скарборо!

Запишись добровольцем прямо сейчас»

В ноябре 1914 года британское побережье подверглось первому нападению, германский флот обстрелял североморский порт Грейт-Ярмут . Поскольку обстрел состоялся в туманную погоду, мешавшую вести прицельный огонь, все снаряды разорвались на пляже, а городу были нанесены незначительные повреждения. Также немецкие корабли предприняли пресечённую британскими эсминцами попытку выставить минное заграждение. Тем не менее, одна британская подводная лодка, пытаясь покинуть гавань, чтобы атаковать корабли противника, подорвалась на мине и затонула. В свою очередь, на обратной дороге один из немецких броненосных крейсеров затонул при столкновении сразу с двумя минами невдалеке от своего порта приписки [65] .

Рейд на Скарборо, Хартлпул и Уитби

Следующий рейд Флота открытого моря к британским берегам произошёл 16 декабря 1914 года, на этот раз бомбардировке подверглись города Скарборо , Хартлпул и Уитби . Жертвами обстрела стали 137 человек, 593 было ранено [66] , большинство из пострадавших были гражданскими лицами. В результате атаки отношение британского общества к немецкому флоту стало резко отрицательным, поскольку направлена она была против мирного населения. Вместе с тем, Королевский флот критиковали за неспособность предотвратить набег [67] [68] .

Обстрел Ярмута и Лоустофта

В апреле 1916 года германское боевое соединение, состоявшее из крейсеров и эсминцев, вновь атаковало прибрежные города Ярмут и Лоустофт . Хотя порты этих городов и представляли некоторую военную ценность, основной задачей рейда считалось выманивание британских кораблей охранения для их последующего уничтожения боевым соединением, либо Флотом открытого моря, стоявшим наготове в этом регионе. Результат набега был неоднозначным: присутствовавшие силы королевского флота были слишком малы для отражения вторжения и предполагаемой погони, и немецкие корабли отступили, прежде чем там появились крупные соединения Гранд-Флита [69] .

Авианалёты

«Гораздо лучше противостоять пулям,

чем погибнуть у себя дома от бомбы

Вступайте в армию прямо сейчас

и помогите отбить авианалёт

Боже, храни короля.»

Начиная с января 1915 года, немецкие цеппелины периодически наносили бомбовые удары по городам восточного побережья Великобритании. Первый налёт был осуществлён 19 января 1915 года на Грейт-Ярмут [70] , 31 мая была проведена бомбардировка Лондона. Британская пропаганда активно использовала эти налёты, демонизируя образ врага, безнаказанно ночью атакующего мирных жителей. Однако реакция населения была неоднозначна: тогда как около 10 000 человек посетили Скарборо, чтобы увидеть последствия артобстрела города, лондонские театры отмечали падение числа зрителей во время «цеппелиновой погоды» — тёмных безветренных ночей [70] .

На протяжении 1917 года Германская империя увеличила производство самолётов-бомбардировщиков, таких как Gotha G.IV , и стала осуществлять налёты с применением этого вида техники. Первый массированный удар пришёлся 25 мая 1917 года на город Фолкстон [70] , позже рейды самолётов-бомбардировщиков довольно быстро полностью заменили налёты дирижаблей. За всю войну цеппелинами было сброшено 6000 бомб, жертвами которых стали 556 убитых и 1357 раненых [71] .

Shortly after the Folkeston bombardment, bombers attacked London - a day raid on June 13, 1917 out of 14 Gotha G. IV planes claimed the lives of 162 East End residents [70] . Responding to this new threat, Major General Edward Bailey Ashmore has developed an advanced detection, control and warning system - the metropolitan surveillance service [72] . Initially, her attention was focused on the capital, later the viewing sector was expanded to the coast of Kent and Essex . The metropolitan surveillance service remained fully operational until the end of the summer of 1918. The last aerial bombardment was carried out on May 19, 1918 [73] .

During the war, the Germans carried out 51 raids with airships on Britain. Another 52 bombings were carried out by airplanes, in total they dropped 280 tons of bombs. The victims of these raids were 1,413 killed and 3409 wounded [74] . The success of the British air defense was very modest: of the 397 aircraft participating in the bombing, only 24 Gotha G.IV aircraft were shot down (another 37 aircraft were lost in various incidents), while it is believed that each of the enemy aircraft was released 14 540 rounds. Protection against airship attacks was more successful: 17 of them were shot down, another 21 were lost due to various kinds of accidents [70] .

Media

Propaganda

Propaganda and censorship were interlinked during the war [75] . Already in September 1914, in order to maintain high morale in society and resist German propaganda, a military propaganda bureau was established under the leadership of Charles Masterman [75] . Under the auspices of the Bureau, such prominent writers as Herbert Wells , Arthur Conan Doyle , Rudyard Kipling , as well as numerous newspaper editors worked [75] .

By the summer of 1915, the bureau issued over 2.5 million copies of books, recordings of speeches, official documents and leaflets [75] . In addition, Masterman oversaw the release of films about the war. One example is the film “The Battle of the Somme” [76] , which appeared on the screens in August 1916 , when the battle itself was not yet over. On August 22, 1916, The Times described the film show as follows: “A large audience was excited and interested in the realities of the war, presented to her so vividly that women sometimes turned a blind eye, unable to see the tragedy of the price of battle depicted in the film; the opinion that everyone probably shares is very reasonable that people can look at what our soldiers are doing in Picardy , for which they fight and suffer ” [77] .

Newspapers

Reproduction of a British propaganda poster in the Russian magazine Niva 1916

In wartime, newspapers, like other media outlets, fell under the Kingdom Protection Act, which limited newspaper publications to two instructions [78] . Instruction 18 forbade the publication of classified information about the movements of troops and the navy. Instruction 27 prevented the spread of “false information” , “data that could adversely affect the appeal indicators” , “information that undermined public confidence in the national currency and banks” , “manifestation of disloyalty to His Majesty” [78] . Censorship functions were assigned to the Press Bureau, which did not have official powers until April 1916, as well as to newspaper owners and their editors who self-censored [6] . Newspaper tycoons who collaborated with the government, such as Viscount Rothemer [79] , Baron Beaverbrook, and Viscount Northcliff [80] , were awarded noble titles. Under these conditions, the state censorship apparatus, by and large, was concentrated only on the control and suppression of socialist magazines and, sometimes, right-wing publications, for example, The Globe . Thus, censorship affected the British press to a lesser extent than a reduction in advertising revenue and an increase in production costs during the war [6] . An additional loophole from state censorship was parliamentary privileges, which allowed to freely publish everything that was said in the country's parliament [78] . One of the most notorious manifestations of censorship at the beginning of the war was a reaction to the sinking of the battleship Odesshes in October 1914. Then it was forbidden to report in newspapers about such a large loss, despite the fact that the witnesses of the death of the ship were numerous passengers of the transatlantic liner " Olympic " , and this was immediately reported by the American press [81] .

The most popular print media of the period under review were The Times , The Daily Telegraph , The Morning Post , and such weekly magazines as The Graphic and John Bull [82] . The need of British society for news from the battlefields has significantly increased newspaper circulation. For example, after the German raid on Hartlepool and Scarborough, the Daily Mail devoted three pages to this event at once, and Evening News reported that the entire circulation of The Times that day was sold out by 9:15 in the morning, even at overpriced prices [83] . Daily circulation of the Daily Mail from 800,000 copies in 1914 increased to 1.5 million in 1916 [6] .

News Magazines

The public need for military news and information was also partially met by news magazines that were entirely dedicated to covering the war. Publications such as The War Illustrated , The Illustrated War News , The War Pictorial , were richly framed with photographs and images, regardless of their target audience. Magazines in which, among others, Herbert Wells , Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling were published, were issued for all walks of life, significantly differing in price and content. The semantic content of the material was also different: in low-cost publications, the main emphasis was on the formation and support of a sense of patriotism to the detriment of the relevance of the news line from the front line. Stories of German war crimes have been published in many publications [84] .

Music

On August 13, 1914, Daily Mail correspondent George Karnock noticed the Irish Regiment of Connaught Rangers marching along Boulogne with the song “The Long Way to Tipperary, ” about which he wrote in a report published on August 18, 1914. The song was picked up by other units of the British Army. In November 1914, she was performed by the famous singer of the music hall Florry Ford , which contributed to the worldwide popularity of the composition [85] . Another widespread marching song that supported the high morale of the British was “ Hide your problems in your old duffel bag ” [86] .

War poets

A serious public outcry was caused by the work of military poets who wrote about their own military experience. Some of them died during the service (the most prominent representatives of this group were Rupert Brook , Isaac Roseberg and Wilfred Owen ), but some (for example, Siegfried Sassoon ) managed to survive. Key poetic themes included soldier youth and naivety, as well as decent behavior with which they fought and died. The line “ They fell facing the enemy " from " Odes of Remembrance " Lawrence Bignon 's Poem " The Fallen , first published in The Times in September 1914. Wartime poets such as Vera Brittain , who worked in the rear, mourned in their works the loss of brothers and lovers who fought at the front [87] .

Fine Art

The events of the First World War were reflected by artists such as Paul Nash and Percy Wyndham Lewis , who went through the trench life and conveyed to the contemporaries the images of the war, being themselves its active participants. Another vision of World War I was offered by the artist George Clausen , who was known at that time for his paintings from the life of the rural outback of England. In 1916 he was sixty-four years old; by this time he was already an academician of painting. In his painting "Sobbing Youth", he returned to the creative manner of his early paintings, created under the influence of French Symbolists. The canvas shows the grief of a young woman (Clausen's youngest daughter - Katherine Francis), who learned about the death of her fiancé during the First World War [88] .

Klausen was later recognized as the creator of paintings and posters on the military theme and took part in the ambitious project The British War Memorials Committee in 1918. For this project, he completed the grandiose painting “The Military Plant in the Woolwich Arsenal ” (1918) [89] .

Consumption Level

As part of the initial business-as-usual policy, the government did not want to control food trade. It resisted attempts to set minimum prices for cereal products, but was forced to establish control over important articles of food imports (sugar, meat and various types of grain). When control was nevertheless introduced, it was of a limited nature. In 1916, it became illegal to order more than two dishes for lunch at public catering facilities and more than three for dinner; fines were introduced for those who fed pigeons or stray animals [33] .

In 1916, the German Empire launched an unlimited submarine warfare , drowning the ships of the Allies, and later the ships of neutral states, carrying food. Thus, an attempt was made to organize hunger in Britain. One of the responses to such a threat was the introduction in February 1917 of a system of voluntary food rationing [33] , personally supported by the king and queen [90] . Since September, bread production has been subsidized. At the initiative of local authorities, from December 1917 to February 1918, a compulsory rationing regime was introduced in different regions of the country [33] , since at that moment wheat stocks at the country's elevators were only enough for six weeks. Some researchers believe that these measures, in general, had a positive effect on the health of the nation [33] , since they regulated the consumption of necessary products. From July 15, 1918, food books for butter, margarine, lard, meat and sugar appeared in everyday life.

During the war, the average energy value of food consumed in calories decreased by only three percent, but protein intake decreased by six percent [33] .

Industry

The total volume of production in Great Britain during the war decreased by 10%, however, in some industries, for example, in the steel industry, growth was noted [7] . Although the country was faced with a shortage of artillery shells during a certain period, this was due to the large volume of government orders in the initial military period, which did not take into account the available production capacities, and not with inefficient production [7] . In 1915, the newly created Ministry of Arms took control of the production of ammunition, and succeeded. In April 1915, about 2 million shells went to France, by the end of the war this figure increased to 187 million [2] . The annual pre-war production of light ammunition by 1918 was carried out in four days. In 1914, 60,000 men and women were involved in the aircraft industry, by 1918 more than 347,000 people were working in this area [7] .

In December 1917, a labor committee was formed in the military cabinet. Belgian refugees were able to get a job, although sometimes they were negatively treated because they occupied British jobs. A similar attitude was with the Irish, freed from military service [91] . Being dissatisfied with the replacement of skilled labor by unskilled labor, caused by the involvement of external groups in the working-age population, in some places the workers tried to organize strikes . Voluntary agreements concluded with trade unions in the early stages of the war, subsequently resulted in a law on military weapons in June 1915, imposed restrictions on the speed of transition of workers from one job to another [92] .

Social Change

During the war, a significant shortage of able-bodied men was repeatedly noted in the country, as a result of which traditional male functions fell on the shoulders of women. First of all, this concerned the arms industry, although it became noticeably closer to the end of the war, as employers always preferred unemployed men [8] . The unions of arms factories also initially hindered the employment of women. Many women entered the public service of His Majesty , where they occupied the posts of men, allowing the latter to go to the front. The number of women involved in the state apparatus increased from 33,000 in 1911 to 102,000 by 1921 [93] . The total increase in the number of employed women in wartime was 1.4 million - from 5.9 to 7.3 million [8] . The membership of women's unions grew by 160%, from 357,000 in 1914 to more than a million in 1918 [93] . At the end of the war, many women were forced to quit in order to vacate their jobs for men returning from the front. Labor agreements between women's unions and employers determined their validity “during the war” [93] .

In the initial stages of World War I, the British government entrusted women with tasks that served as a continuation of their traditional roles, for example, in organizing assistance to Belgian refugees or in facilitating the recruitment of men in the army. The so-called Order of the White Feather dealt with this mission (a white feather, in a sign of cowardice, was given to men who did not join the army) and who organized grocery parcels for men at the front. In February 1916, the first initiative groups appeared that involved women in agricultural work. And in March 1917, the Women's Agricultural Army was created, specializing in this type of activity. However, its members received less salary than their male counterparts. According to estimates by the Ministry of Commerce, by 1918, 148,000 women were involved in the country's agriculture, although there was a figure of approximately 260,000 people [8] .

The war split the British suffragist movement. The bulk of the movement's supporters, in the form of the Women's Socialist and Political Union , led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel , supported the government line, held demonstrations for the rights of women to serve their own country on equal terms with men [8] . A more radical wing of the movement, the Women's Suffrage Federation , led by Emmeline's other daughter, Sylvia Pankhurst , distanced herself from the rest, expressed her rejection of the war, some members of the organization harbored people who evaded conscription.

Women were allowed to serve in the armed forces of the country [8] , and by the end of the war, about 80,000 women served in the British Army, in positions not directly related to hostilities, such as nurses and cooks [94] .

At the end of the war, millions of demobilized soldiers returning to their homeland still did not have the right to vote [14] . This state of affairs put the political elite in a difficult position, because people who fought for the preservation of the existing democratic state system could not vote in the elections. Закон о народном представительстве , подписанный королём в феврале 1918 года, был призван решить эту проблему, предоставив избирательное право всем взрослым мужчинам — главам семейств старше 21 года [14] . Закон также наделял правом голоса женщин старше 30 лет, проходивших по минимальному имущественному цензу . Эта акция преподносилась как признание вклада женщин-работниц оборонных предприятий [14] . Позднее, в том же году, вышел закон о женском парламентском цензе , позволявший женщинам старше 30 лет становиться членами британского парламента.

Подводя итог, можно сказать, что в ходе войны и после её окончания были ликвидированы некоторые социальные барьеры, сформированные во время Викторианской и Эдвардианской эпох [2] .

Потери

В послевоенной публикации военного министерства «Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War 1914—1920» , изданной в марте 1922 года, официально числится погибшим 908 371 солдат. Этот отчёт не делил жертвы войны на более подробные категории и охватывал как погибших в ходе боевых действий , так и умерших от ран либо в плену , а также пропавших без вести. В то же время, в книге приведены сведения по основным колониям и доминионам Британской империи. Так, Соединённое королевство Великобритании и Ирландии потеряло в ходе войны 704 121 человека, Британская Индия — 64 449 человек, Канада — 56 639 человек, Австралия — 59 330 человек, Новая Зеландия — 16 711 человек и, наконец, Южно-Африканский Союз — 7121 человека [9] . Потери Королевского военно-морского флота (включая Королевскую военно-морскую авиационную службу, числившуюся в составе флота до 31 марта 1918 года) также вынесены особо и составляют 32 287 человек погибшими и пропавшими без вести. Торговый флот потерял 14 661 человека. Цифры по Королевскому лётному корпусу и наследовавшим ему Королевским ВВС — в отчёте не приведены вовсе [9] .

Следующая заметная публикация вышла в 1931 году и называлась «Casualties and Medical Statistics of the Great War» , являясь последним томом серии «Medical History of the War» . В книге жертвы армии Британской империи в Первой мировой подразделены по причинам смерти [10] . В итоге, всеобщие потери в период с 1914 по 1918 годы составляли 876 084 человека, из которых 418 361 человек убит в бою, 167 172 умерло от ран, 113 173 человека умерло вследствие заболеваний или травм, 161 046 пропало без вести и считаются погибшими, 16 332 человека умерло в плену [10] .

Показатель смертности среди гражданского населения составил 292 000 человек и включал в себя 109 000 погибших из-за нехватки продовольствия и 183 577 жертв эпидемии испанского гриппа [9] . Отчёт военного министерства 1922 года упоминал погибшими вследствие авианалётов и морского обстрела побережья 1260 человек гражданских лиц и 310 человек военнослужащих Соединённого Королевства [95] . Потери в море от действий вражеских подводных лодок составили 908 штатских и 63 рыбака [96] .

Memory

В течение нескольких лет после окончания войны, в местах былых боёв, были заложены сотни воинских кладбищ и мемориалов. Для их организации, учёта и опеки ещё во время войны была учреждена Имперская комиссия по уходу за военными захоронениями . В её основе стояло межправительственное соглашение шести стран Британской империи: Великобритании, Канады, Австралии, Новой Зеландии, Индии и ЮАС. Сейчас на попечении комиссии Содружества наций по уходу за военными захоронениями (современное название данной организации) находятся около 2500 кладбищ в 150 странах мира [97] . В разработке типового дизайна мемориалов комиссии приняли ведущие архитекторы того времени: Герберт Бейкер , Реджинальд Бломфельд и Эдвин Лаченс . Так появились стандартные элементы воинских кладбищ комиссии: жертвенный крест и камень поминовения . Автором первого элемента был Бломфельд, как правило, крест устанавливается на кладбищах, состоящих из 40 могил и больше. Камень поминовения является центральным объектом кладбищ от 1000 могил и больше. Он был создан по проекту Эдвина Лаченса. Ключевая деталь камня — надпись-посвящение « Их имена будут жить вечно » . Она была внесена по предложению Редьярда Киплинга , потерявшего на этой войне единственного сына [98] .

In Great Britain, as in many other countries of the Commonwealth of Nations , the day of the signing of the Compiegne Armistice , which ended the First World War , is widely celebrated . In the countries of the Commonwealth common multiple of the holiday: Memorial Day , Armistice Day , Veterans Day , Day poppies . The Royal Decree on celebrations on this day was signed by George V on November 7, 1919 [99] . The symbol of the holiday is a red memorial poppy . This image was taken from John McCray 's poem " On the Fields of Flanders ”and is associated with poppy flowers that covered the fields of the most desperate battles in Flanders . The bright red color of the festive symbolism is associated with the shed blood of the victims of the war. There is a tradition of wearing buttonholes in the form of red poppies, on the lapel, in the buttonhole of a jacket or other outerwear. It is followed by both ordinary citizens and the royal family, representatives of the country's political elite and public figures. These days, poppy symbols adorn public and private transport, newspapers.

Formally, it is believed that hostilities were completed at 11 a.m. on the eleventh day of the eleventh month, that is, November 11th. At this time, a minute of silence reigns throughout the United Kingdom. Although the main events take place on the memorial Sunday closest to this day. They include the laying of poppy wreaths at numerous monuments and memorials related to the war. The main ceremony takes place in central London, in Whitehall . It involves the first persons of the state, leaders of the main political parties, representatives of the clergy of the main British denominations, the highest ranks of all military branches, representatives of the merchant fleet, coast guard and other services. Members of the royal family walk past the Foreign Office to the cenotaph . After which all those present wait until Big Ben hits 11 o’clock in the morning, then a cannon shot of the Royal Horse Artillery follows and a two-minute silence ensues. At the end of a minute of silence, to the sounds of the horns, the queen and senior members of the royal family lay wreaths at the foot of the cenotaph, followed by the rest of the procession. The solemn part ends with the universal performance of the national anthem .

Until 2008, the last British veterans of World War I took part in the capital's ceremony: Bill Stone , Henry Ellingham and Harry Patch . They were representatives of various military branches. Stone served in the Navy, Ellingham was an aviator, and Patch was an infantryman. All three died in 2009.

Consequences

The war caused severe damage to the UK economy . From the world's largest foreign investor, it has turned into one of the largest debtors; interest payments accounted for up to 40% of government spending . The inflation rate more than doubled between 1914 and 1920 (when inflation reached its peak) [100] . The purchasing power of the pound has fallen by 61.2%. German reparations , received in the form of free coal , led to a crisis of their own coal industry and became one of the reasons for the general strike of 1926 [101] . Overseas private investment during the war was sold, bringing in 550 million pounds of profit. On the other hand, the volume of new investments during this period amounted to 250 million pounds. Thus, the volume of financial investments during the war decreased by 300 million pounds [102] . Material losses were relatively small: the most significant loss was 40% of the British merchant fleet sunk by German submarines in wartime . The number of ships was almost completely restored by 1918, and completely at the end of the war [103] . Formulating the conclusion about economic damage, military historian Correlli Barnett noted that “the objective truth is that the Great War did not inflict critical economic damage on Britain ...” , the war only “psychologically mutilated the British” [104] .

The losses and shocks suffered deep psychological scars to British society. The optimism of the 1900s completely disappeared, the youth who passed through the battlefields went down in history as the “ Lost Generation ” , which never recovered from its experience. The 1921 census revealed the post-war demographic situation in the country. According to the census, 19,803,022 women in England and Wales were only 18,082,220 men. The prevailing difference of 1.72 million in the newspapers called "two million surplus" [105] . In 1921, out of 1209 women aged 25 to 29, there were only 1,000 male peers. By 1931 (the year of the next census in the United Kingdom), 50% of these women were still unmarried, and 35% had never married [106] .

A less definite, but still significant change can be considered the growth of national identity of the dominions of the British Empire. Battles such as the Gallipoli Campaign for Australia and New Zealand and the Battle of Vimy for the Canada Ridge became examples of national pride and, at the same time, determined the dominions' desire for greater independence and less dependence on the United Kingdom. These battles are generally regarded by national propaganda as symbols of their power during the war. In addition, the war spurred the development of hidden nationalism in the British colonies and mandated territories , where the population tried to realize their aspirations for self-determination , in the fashion and likeness of the newly formed countries of Eastern Europe . As a result, Britain faced riots in Ireland (1919-1921), India (1919), Egypt (1919-1923), Palestine (1920-1921) and Mesopotamia (1920) [11] . The only territorial loss of the British crown was Ireland [11] , where a delay in the commissioning of Gomrul, coupled with the Easter uprising of 1916 and an unsuccessful attempt to force enlistment, provoked an increase in separatist sentiments in the region, which ultimately led to the outbreak of the Irish war for independence in 1919.

As a result of the war, the colonies of the defeated German and Ottoman empires became subordinate to the Entente countries under the mandates of the League of Nations . Following the conclusion of the Versailles Peace Treaty, the United Kingdom expanded its holdings by 4,700,000 km² and received 13 million new subjects [107] . As a result, Great Britain gained control over Palestine and Transjordan , Mesopotamia , parts of Cameroon and Togo , as well as Tanganyika [108] . Thus, the British Empire reached the limit of its territorial development [11] .

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Encyclopedia of World War I / S. Tucker; P. Roberts. - 2005 .-- P. 504.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 The war and the changing face of British society . The National Archives . Date of treatment August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ Vadim Serov. Dictionary of winged words and phrases . M .: "Lokid-Press" (2003). Date of treatment September 5, 2011. Archived on May 21, 2012.

- ↑ 1 2 3 C. Baker. Government control ... - 1921. - P. 21.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Chris Trueman. Total War (English) . History Learning Site. Date of treatment August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 394-395.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 341-343.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 455-460.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 HMSO. Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the WWI. - 1922. - P. 237-362.

- ↑ 1 2 3 TJ Mitchell. Casualties & Medical Statistics of the WWI. - 1997 . - P. 12.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 564.

- ↑ 1 2 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 38-39.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 499-500.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Hugh Fraser. The Representation of the People Act, 1918 with Explanatory Notes . - L .: Sweet and Maxwell Limited, 1918. - 812 p.

- ↑ David Boothroyd. General Election Results 1885–1979 . Date of treatment August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ H. Nicolson. King George V. - 1984. - P. 308.

- ↑ The Royal Family name . Official website of the British monarchy .. Date accessed August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ H. Nicolson. King George V. - 1984 .-- P. 310.

- ↑ Text of the Titles Deprivation Act 1917 and of the Order-in-Council of March 28, 1919 effecting the deprivation of titles. (eng.) . heraldica.org. Date of treatment August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ H. Nicolson. King George V. - 1984. - P. 301.

- ↑ K. Rose. King George V. - 1984. - P. 210.

- ↑ Duke of Windsor. A King's Story. - 1999. - P. 106-107.

- ↑ P. Ziegler. King Edward VIII. - 1991. - P. 48-50.

- ↑ Duke of Windsor. A King's Story. - 1999 .-- P. 109.

- ↑ Duke of Windsor. A King's Story. - 1999 .-- P. 140.

- ↑ P. Ziegler. King Edward VIII. - 1991 .-- P. 111.

- ↑ S. Bradford. King George VI. - 1989. - P. 55-76.

- ↑ Princess Mary's Gift to the Troops, Christmas 1914 . Imperial War Museum Collections . Date of treatment August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. xix.

- ↑ 1 2 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 348.

- ↑ First Publication of the Kingdom Protection Act: Basic Provisions , London Gazette (14 August 1914), C. A2. Date of treatment August 10, 2011.

- ↑ 1 2 First Publication of the Kingdom Protection Act: Port Protection and Communications Regulations , London Gazette (August 14, 1914). Date of treatment August 10, 2011.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007. - P. 380-382.

- ↑ 1 2 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 383.

- ↑ Treachery Bill . Hansard - The official record of the meetings of the English Parliament. Date of treatment August 11, 2011.

- ↑ British Army: Courts Martial and Deserters, 17th-20th Centuries . The National Archives . Date of treatment August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ P. Panayi. Germans in Britain. - 1996 .-- P. 73.

- ↑ Panikos Panayi. Anti-German Riots in London during the First World War . Oxford Journals. Date of treatment August 12, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ P. Panayi. Germans in Britain. - 1996. - P. 89-90.

- ↑ P. Panayi. Germans in Britain. - 1996 .-- P. 115-118.

- ↑ P. Panayi. Germans in Britain. - 1996 .-- P. 118.

- ↑ P. Panayi. Germans in Britain. - 1996. - P. 119-120.

- ↑ P. Panayi. Germans in Britain. - 1996. - P. 120-123.

- ↑ P. Panayi. Germans in Britain. - 1996. - P. 127-129.

- ↑ Liz Palika. German Shepherd Dog: Your Happy Healthy Pet . - Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing, 2008 .-- P. 22 .-- 144 p. - ISBN 0-470-19231-3 .

- ↑ History of the Breed . www.germanshepherds.com. Date of treatment August 12, 2011.

- ↑ I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 289.

- ↑ Zayonchkovsky A. M. [1 World War I]. - 2000. - S. 8-11.

- ↑ The Oxford History of the British Army / D. Chandler. - 2003 .-- P. 211.

- ↑ L. Sondhaus. Naval Warfare, 1815-1914. - 2001 .-- P. 161.

- ↑ [130 History of the First World War of 1914-1918] / edited by I. I. Rostunov. - 1975. - T. 1. - S. 130.

- ↑ The Battle of Jutland 1916 . www.royalnavy.mod.uk. Date of treatment August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ D. Keegan. World War I. - 2004 .-- S. 345.

- ↑ I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 254.

- ↑ History of The Royal Air Force at World War I. www.raf.mod.uk. Date of treatment August 12, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 291-295.

- ↑ D. Keegan. World War I. - 2004 .-- S. 348-349.

- ↑ UK Military Service Act . Date of treatment August 11, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ Conscientious Odjection in Britain during the First World War . Peace Pledge Union. Date of treatment August 11, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 507.

- ↑ A. J. P. Taylor. English History 1914-1945. - 1975 .-- P. 116.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of World War I / S. Tucker; P. Roberts. - 2005 .-- P. 709.

- ↑ Corbett Julian. Yorkshire Coast Raid, December 15-16, 1914 . Date of treatment August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ R. Massie. Castles of Steel. - 2004 .-- P. 309-311.

- ↑ HMSO. Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the WWI. - 1922. - P. 677.

- ↑ Damage by German Raids . Hansard - The Official Record of the Meetings of the English Parliament (1 March 1915). Date of treatment August 12, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ German Attacks on Unfortified Towns . Hansard - The Official Record of the Meetings of the English Parliament (June 24, 1915). Date of treatment August 12, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ European powers in the WWI / S. Tucker. - 1996. - P. 293-294.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 258-261.

- ↑ B. Powers. Strategy Without Slide-rule. - 1976. - P. 50-51.

- ↑ JM Bourne. Who's Who in WWI. - 2001 .-- P. 10.

- ↑ JM Bourne. Who's Who in WWI. - 2001 .-- P. 20.

- ↑ Air Raids . The National Archives . Date of treatment August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Espionage, Propaganda and Censorship . The National Archives . Date of treatment August 10, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ The Battle of the Somme on the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ War's Realities on the Cinema (English) , The Times (22 August 1916), p. 3.

- ↑ 1 2 3 A Call to Arms / T. Paddock. - 2004 .-- P. 22.

- ↑ First Publication of the Award Announcement , London Gazette (1 July 1919). Date of treatment August 10, 2011.

- ↑ First Publication of the Award Announcement , London Gazette (February 19, 1918). Date of treatment August 10, 2011.

- ↑ A Call to Arms / T. Paddock. - 2004 .-- P. 24.

- ↑ A Call to Arms / T. Paddock. - 2004 .-- P. 18.

- ↑ A Call to Arms / T. Paddock. - 2004 .-- P. 34.

- ↑ War Weeklies , Time (September 25, 1939). Date of treatment June 12, 2009.

- ↑ M. Cryer. Love Me Tender. - 2008 .-- P. 188.

- ↑ J. Shepherd. Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music. - 2003 .-- P. 390.

- ↑ Anita Singh. Vera Brittain to be Subject of Film . The Daily Telegraph (February 13, 2009). Date of treatment August 11, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ Stout, Janis P. Coming Out of War: Poetry, Grieving, and the Culture of the World Wars . - University of Alabama Press, 2016 .-- 294 p. - ISBN 9-780-8173-5862-4.

- ↑ In the Gun Factory at Woolwich Arsenal, 1918 . Imperial War Museum London. Date of treatment April 23, 2017.

- ↑ D. Condell; J. Liddiard. Working for Victory ?. - 1987 .-- P. 18.

- ↑ I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 366.

- ↑ I. Beckett. The great war. - 2007 .-- P. 369.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Joanna Bourke. Women on the Home Front in World War One . BBC Date of treatment August 11, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ Joanna Bourke. Women and the Military during World War One . BBC Date of treatment August 11, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ M. Gilbert. Atlas of WWI. - 1994. - P. 74-78.

- ↑ M. Gilbert. Atlas of WWI. - 1994 .-- P. 78.

- ↑ Website of the Commonwealth Commission for the Care of War Graves . Date of treatment August 17, 2011.

- ↑ Stone of Remembrance: Their Name Liveth Forevermore . Australian Government Department of Veterans' Affairs. Date of treatment August 17, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ The Remembrance Ceremony . Date of treatment August 22, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ Inflation value of the Pound . House of Commons. Date of treatment September 12, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ Keith Laybourn. The general strike of 1926 . - Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993 .-- P. 27. - 161 p. - ISBN 0-719-03865-0 .

- ↑ A. J. P. Taylor. English History 1914-1945. - 1975 .-- P. 123.

- ↑ A. J. P. Taylor. English History 1914-1945. - 1975 .-- P. 122.

- ↑ C. Barnett. The Collapse of British Power. - 2002 .-- P. 424-426.

- ↑ Virginia Nicholson. Singled Out: How Two Million British Women Survived Without Men After the First World War. - Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008 .-- P. 22-23. - 312 p. - ISBN 0-195-37822-9 .

- ↑ Amanda Cable. Condemned to Be Virgins: The Two Million Women Robbed by the War . Daily Mail (September 15, 2007). Date of treatment August 17, 2011. Archived January 31, 2012.

- ↑ N. Ferguson. Empire. - 2004 .-- P. 315.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the British Empire / J. Olson; R. Shadle. - 1996. - Vol. 1 .-- P. 658.

Sources

- in Russian

- The history of the First World War of 1914-1918 / edited by I.I. Rostunova . - in 2 volumes. - M .: Nauka , 1975 .-- 25,500 copies.

- Zayonchkovsky A.M. World War I. - SPb. : Polygon, 2000 .-- 878 p. - ISBN 5-89173-082-0 .

- John Keegan . World War I. - M .: AST , 2004 .-- 576 p. - 4000 copies. - ISBN 5-170-12437-6 .

- in English

- Charles Whiting Baker. Government control and operation of industry in Great Britain and the United States during the World War . - 1. - N. Y .: Oxford University Press , 1921. - 138 p.

- Correlli Barnett . The Collapse of British Power. - L .: Pan Macmillan, 2002 .-- 688 p. - ISBN 0-330-49181-4 .

- Ian Beckett. The great war . - 2. - Harlow: Pearson Education, 2007 .-- 813 p. - ISBN 1-405-81252-4 .

- JM Bourne. Who's Who in World War One . - 1. - New York, NY: Routledge , 2001 .-- 316 p. - ISBN 0-415-14179-6 .

- Sarah Bradford. King George VI. - L .: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1989 .-- 506 p. - ISBN 0-297-79667-4 .

- The Oxford History of the British Army / David Chandler. - 2. - Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 .-- 485 p. - ISBN 0-192-80311-5 .

- Diana Condell; Jean Liddiard. Working for Victory ?: Images of Women in the First World War, 1914-18 . - 1. - London: Routledge , 1987. - 201 p. - ISBN 0-710-20974-6 .

- Max Cryer. Love Me Tender: The Stories Behind the World's Best-loved Songs . - London: Frances Lincoln ltd, 2008 .-- 192 p. - ISBN 0-711-22911-2 .

- Duke of Windsor . A King's Story: The Memoirs of the Duke of Windsor. - L .: Prion Books, 1999 .-- 440 p. - ISBN 1-853-75303-3 .

- Hugh Fraser. The Representation of the People Act, 1918 with Explanatory Notes . - L .: Sweet and Maxwell Limited, 1918. - 812 p.

- Niall Ferguson . Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power . - N. Y .: Basic Books , 2004 .-- 351 p. - ISBN 0-465-02329-0 .

- Martin Gilbert. Atlas of World War I. - 2. - Oxford: Oxford University Press , 1994 .-- 164 p. - ISBN 0-195-21075-1 .

- HMSO . Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War, 1914–1920 . - 1922. - 879 p.

- Robert K. Massie. Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. - New York, NY: Random House, 2004 .-- 884 p. - ISBN 0-345-40878-0 .

- Thomas Mitchell. Casualties and Medical Statistics of the Great War. - L .: Battery Press, 1997 . - 382 p. - ISBN 0-898-39263-2 .

- Harold Nicolson. King George the Fifth: His Life and Reign. - L .: Constable and Co., 1984. - 568 p. - ISBN 0-094-65720-3 .

- Historical Dictionary of the British Empire / James Stuart Olson, Robert Shadle. - Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group , 1996. - Vol. 1. - 632 p. - ISBN 0-313-29366-X .

- A Call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War / Troy Paddock. - 1. - Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group , 2004. - 212 p. - ISBN 0-275-97383-2 .

- Panikos Panayi. Germans in Britain since 1500 . - L .: Continuum International Publishing Group , 1996 .-- 266 p. - ISBN 1-852-85126-0 .

- Barry D. Powers. Strategy Without Slide-rule: British Air Strategy, 1914-1939 . - L .: Taylor & Francis , 1976. - 295 p. - ISBN 0-856-64219-3 .

- Kenneth Rose King George V. - 3. - L .: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1984. - 514 p. - ISBN 0-297-78245-2 .

- John Shepherd. Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World . - 1. - London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003. - 832 p. - ISBN 0-826-46321-5 .

- Lawrence Sondhaus. Naval Warfare, 1815-1914 . - 1. - London: Routledge , 2001. - 263 p. - (Warfare and History). - ISBN 0-415-21478-5 .

- A. J. P. Taylor . English History 1914-1945 . - Oxf. : Oxford University Press , 1975 .-- 708 p. - ISBN 0-198-21715-3 .

- The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social, and Military History / Spencer Tucker, Priscilla Mary Roberts. - Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO , 2005 .-- 1661 p. - ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2 .

- The European powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia / Spencer Tucker. - New York, NY: Routledge , 1996 .-- 783 p. - ISBN 0-815-30399-8 .

- Philip Ziegler. King Edward VIII: The Official biography. - London: Fontana Press, 1991 .-- 654 p. - ISBN 0-006-37726-2 .