In mathematics , if two groups ( G , ∗) and ( H , •) are given, the homomorphism of groups from ( G , ∗) to ( H , •) is a function h : G → H , such that for all u and v of G is performed

where the group operation to the left of the "=" sign refers to group G , and the operation to the right refers to group H.

From this we can deduce that h maps the neutral element e G of the group G into the neutral element e H of the group H , and also maps the inverse elements into the inverse in the sense that

Thus, we can say that h "preserves the group structure".

In earlier papers, h ( x ) could be denoted as x h , although this can lead to confusion with indices. Recently, there has been a tendency to omit brackets when writing a homomorphism, so that h ( x ) simply turns into xh . This trend is particularly noticeable in the areas of group theory, where automation is applied, since it is in better agreement with the accepted automaton reading from left to right.

In areas of mathematics, where groups are supplied with additional structures, the homomorphism is sometimes understood as a mapping that preserves not only the structure of the group (as above), but also an additional structure. For example, a homomorphism of topological groups is often assumed to be continuous.

Content

Concept

The goal of defining a group homomorphism is to create functions that preserve the algebraic structure. Equivalent definition of a group homomorphism: The function h : G → H is a group homomorphism if a ∗ b = c implies h ( a ) ⋅ h ( b ) = h ( c ). In other words, the group H is in some sense similar to the algebraic structure of G and the homomorphism h preserves it.

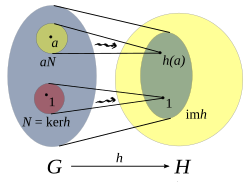

Image and Core

Define the kernel h as a set of elements from G that are mapped to a neutral element in H

and the image of h as

The kernel h is a normal subgroup of G , and the image of h is a subgroup of H :

A homomorphism h is injective (and is called a monomorphism of a group ) if and only if ker ( h ) = { e G }.

The kernel and image of a homomorphism can be understood as a measure of how close the homomorphism is to isomorphism. The first isomorphism theorem states that the image of the homomorphism of the group h ( G ) is isomorphic to the factor group G / ker h .

Examples

- Take the cyclic group Z / 3 Z = {0, 1, 2} and the group of integers Z by addition. The mapping h : Z → Z / 3 Z with h ( u ) = u mod 3 is a homomorphism. It is surjective and its core consists of integers divisible by 3.

- Take a group

- For any complex number u, the function f u : G → C , defined as:

- is a homomorphism.

- Take a group of positive real numbers with the multiplication operation ( R + ,). For any complex number u, the function f u : R + → C , defined as

- is a homomorphism.

- The exponential map is a homomorphism from the group of real numbers R by addition to the group of non-zero real numbers R * by multiplication. The kernel is the set {0}, and the image consists of real positive numbers.

- The exponential map also forms a homomorphism from the group of complex numbers C by addition to the group of nonzero complex numbers C * by multiplication. This mapping is surjective, its core is the set {2π ki : k ∈ Z }, as can be seen from Euler’s formula . Fields like R and C that have a homomorphism from a group by addition to a group by multiplication are called .

Group categories

If h : G → H and k : H → K are group homomorphisms, then k o h : G → K is also a homomorphism. This shows that the class of all groups, together with homomorphisms of groups as morphisms, form a category .

Types of homomorphic mappings

If the homomorphism h is a bijection , then it can be shown that the inverse map is also a group homomorphism, and then h is called an isomorphism . In this case, the groups G and H are called isomorphic — they differ only in the designation of elements and operations and are identical for practical use.

If h : G → G is a homomorphism of groups, we call it an endomorphism of G. If it is also bijective and, therefore, is an isomorphism, it is called an automorphism . The set of all automorphisms of a group G with a composition of functions as an operation itself forms a group, a group of automorphisms of G. This group is denoted as Aut ( G ). As an example, the automorphism of the group ( Z , +) contains only two elements, the identity transformation and multiplication by −1, and it is isomorphic to Z / 2 Z.

An epimorphism is a surjective homomorphism, that is, a homomorphism on . A monomorphism is an injective homomorphism, that is, a one-to-one homomorphism.

Homomorphisms of abelian groups

If G and H are Abelian (that is, commutative) groups, then the set Hom ( G , H ) of all homomorphisms from G to H is itself an Abelian group — the sum h + k of two homomorphisms is defined as

- ( h + k ) ( u ) = h ( u ) + k ( u ) for all u from G.

The commutativity of H is needed to prove that h + k is again a group homomorphism.

Also homomorphisms are compatible with the composition of homomorphisms in the following sense: if f belongs to Hom ( K , G ), h , k are elements of Hom ( G , H ), and g belongs to Hom ( H , L ), then

- ( h + k ) o f = ( h o f ) + ( k o f ) and g o ( h + k ) = ( g o h ) + ( g o k ).

This shows that the End ( G ) set of all endomorphisms of the Abelian group forms a ring , group G. For example, the endomorphism ring of an abelian group consisting of a m copies of Z / n Z is isomorphic to the ring of m-by-m matrices with elements from Z / n Z. The above-mentioned compatibility also shows that the category of all abelian groups with homomorphisms forms a preadditive category . The existence of direct sums and kernels with well-conditioned behavior makes this category an example of an abelian category .

See also

Links

- DS Dummit, R. Foote. Abstract Algebra. - 3. - Wiley, 2004. - pp. 71-72. - ISBN 9780471433347 .

- Leng S. Algebra. - Moscow: World, 1968.