The second nameless tower is the tower of the southern wall of the Moscow Kremlin , which runs along the Moscow River . It was erected in the 1480s, was destroyed several times and was restored again. It is one of the lowest Kremlin towers - its height is 30.2 meters. Located east of the First Nameless Tower [1] [2] .

| Second Nameless Tower | |

|---|---|

View of the tower from the Kremlin Embankment , 2009 | |

| Location | Moscow |

| Kremlin | the Moscow Kremlin |

| Year built | 1480s |

| The shape of the base of the tower | Chetverik |

| Tower height | 30.2 meters |

| |

| Object of cultural heritage of Russia of federal significance reg. № 771510302110266 ( ЕГРОКН ) (Wikigid database) |

Content

Origin of title

The names of the Kremlin towers changed several times depending on the functions and the surrounding buildings. The towers, called the Nameless, were located on the edge of the hem - the lower part of the Kremlin - and therefore did not receive the characteristic names [3] [4] .

History

Construction

Written sources record the data on travel and corner towers of the Kremlin, but the exact dates of construction of intermediate deaf structures are not known [5] . In the annals , especially important events in the history of Moscow were usually recorded, and some documents could have been completely lost during fires and other disasters. Researchers suggest that the Second Untitled Tower was erected simultaneously with other fortifications of the southern wall in the 1480s [6] [7] [8] . Presumably, the architect of the tower was Italian architect Antonio Fryazin , invited to Moscow by Ivan III and built all the fortifications of the Moskvoretsky wall [5] . The material for the new Kremlin fortifications served as a brick with blockage of cobblestone and white stone on a lime mortar. The tower stands slightly outside the fortress wall [9] .

Initially, the tower served only fortification functions . At its base lay a squat chetverik , and served as the end of a wooden pitched roof. It is known that during the fire of 1493 on the walls of the newly built brick Kremlin “the hail roof was all burned” [10] [11] . More detailed information about the structure of the roofs of the Kremlin buildings chronicle sources do not contain. However, scientists believe that they were built immediately after the laying, so as not to expose wooden bridges and floors to the harmful effects of atmospheric precipitation [12] . The tower also had a passage gate, but it is not known whether they were built during construction or later [13] [14] .

Some historians suggest that in the Middle Ages, all the Kremlin towers were connected by intra-passages and could also pass through the Second Nameless Tower. Proof of this is the Moscow-based Godunov Plan , where intra-wall loopholes are visible throughout the Kremlin wall [15] . Other researchers believe that the old tower had no passage or internal passages [5] . There are no reliable sources confirming the existence of the caches of the Second Nameless Tower. If they were laid, they could have suffered during the fire of 1547 , when powder stores exploded in the neighboring First Nameless Tower [16] .

Changes in the 17th Century

By the middle of the XVII century, the tower was highly dilapidated [17] [18] . On the state of the Kremlin buildings shows an inventory of dilapidated 1646:

[at the gate of the Second Nameless Tower] the stone shoot is broken out all, you cannot climb the city. From the same gate to the Deaf [1st Nameless] tower among the pryasla the wooden lattice is spoiled and that guard has no lattice, but the diak lives at that lattice [19] .

Despite the fact that in 1658 the tower was repaired, by 1667 it again required renovation [20] . In the inventory for this year it says:

In her shoot in the doorway and split bricks hang. In it, in two places, the vault average fell through, bricks in twenty, and in the third place, the vault spread, and in two places, the walls between vaults settled. From it, the exit above the doors on top of the arch spread across the battlements and three bricks fell out, and there is a roof on it [21] [22] .

In the 1660s-1680s, the Second Nameless Alongside with other Kremlin towers was modernized. Until the 17th century, a low wooden tent with a weather vane , which burned several times during fires, served as the end of the strelnitsa. When rebuilding it was replaced with a brick parapet with pants, typical of the modern look of all the Kremlin towers [23] . During the modernization, the main quadrangle of the tower was built on a quadrant with a four-sided tent and a watchtower [6] , topped with an octahedral tent with a weather vane [18] . The machiculi done at the beginning of the century in the 1680s were laid from the inside and began to perform only a decorative function [24] [25] .

As an intermediate riverine tower, the Second Anonymous received a low completion, which did not interfere with the review of the Kremlin ensemble on the south side [26] . The upper part of the tower resembles the neighboring Moskvoretsky gunfire - First Nameless , Taynitskaya and Blagoveshchenskaya . At the bottom of the Second Anonymous Tower for some time housed a forge and travel gates were arranged [27] . Shoot from the ground the tower did not have. The bau-adjutant of the Grand Kremlin Palace, Mikhail Fabricius, when describing the towers of the southern Kremlin wall, noted their similarity to the wooden tent architecture: “Shatoobraznuyu cover windows, broken down, these protrusions with a detour around the tops - is it not a form inherent in the construction of wood? " [28]

Changes in the 18th Century

At the beginning of the 18th century, by order of Peter I , a detailed inventory of the fortifications was carried out. The towers of the Kremlin were measured and described in detail with an indication of the height, length and width [29] . The inventory reported that at the Second Nameless Tower there had once been cut through a passage gate, which had already been sealed with a chaos and closed with an iron grid [6] [17] .

In the midst of the Northern War , fearing the attack of the Swedish troops on Moscow, the emperor ordered the Kremlin towers to be strengthened and prepared for defense [30] . The emphasis was placed on the bastion defense system, and in 1707–1709 a double earthen wall was erected on the south side to protect the approaches to the Moscow towers [31] [32] . In a letter to Tsarevich Alexei Peter I, it was said: "On the Moscow River, between the Taynitsky and Moskvoretsky gates, they leave it with logs and fill it with earth and make a parapet" [33] . In addition, guns were installed on the towers and loopholes were re-punched [34] . After victory in the Battle of Poltava, the towers began to be decorated during ceremonial events [35] .

In 1713, the capital was moved to St. Petersburg , and the threat of the attack of Charles XII's troops on Moscow was over. Kremlin fortresses ceased to play an important role and were gradually abandoned [36] . The brickwork of the walls and towers of the southern Kremlin wall collapsed because of the proximity of water, the earthen ramparts turned into swollen hills, garbage was accumulating in defensive moats. The wooden floors and details of the fortifications were burned during the fire of 1737 [37] . In 1760, architect K. I. Blank proposed “to repair damage in the same manner,” but the project did not materialize [38] .

In 1771, for the construction of the Grand Kremlin Palace , designed by architect Vasily Bazhenov , the First Nameless and Taynitsky towers, as well as part of the southern wall, were destroyed [39] . It is believed that the Second Nameless Tower was dismantled together with other historical monuments of the Kremlin [6] [40] [18] [1] . However, this version is not supported by written sources [41] [42] . Thus, on drawings and plans made in 1867 by a draftsman N. I. Antonov and architect Peter Gerasimov , it was indicated that this tower was erected at the end of the 15th century with a height of 14 1/3 sazhen. [43]

Changes in the XIX Century

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Moscow Kremlin came under the control of the chief chief of the Palace department, Peter Valuev [44] . According to his testimony, the Kremlin buildings at that time were in a dilapidated, neglected state and inside the walls "there was great uncleanness" [45] . Under Valuev, Peter’s bastions were completely destroyed, and in 1802 a large-scale reconstruction of the dilapidated walls and towers of the Kremlin began. In 1805–1807, the Second Untitled Tower was restored: the tent was covered with new glazed tiles , the weather vane and white stone ornaments were renewed, the structure's parapets were laid out with white stone plates, and the floor of the site was lined with fresh bream [46] . According to historians, after repairing the tower was in good condition [47] .

During the occupation of Moscow by French troops in 1812, many Kremlin buildings were damaged [48] . Leaving the capital, Napoleon gave the order to mine the Kremlin, but the Second Anonymous Tower survived [41] .

Due to the lack of funds, the restoration of the destroyed fortifications was started only three years later. In 1815, Prince Nikolai Yusupov , head of the Kremlin expedition, ordered two wall gaps to be built up from the Moscow River [49] [6] . From 1816 to 1835, a large-scale renovation of the Moscow Kremlin was carried out and the territories adjacent to it were ennobled, including near the tower. In 1819, Petrovsky bastions were finally demolished, and the remaining land was used for the embankment by planting two rows of trees [50] .

The brick and white stone in the basement are constantly refined and collapsed due to the proximity of the Moscow River. During the XIX century, the Kremlin fortifications were repaired several times [51] . In 1860-1861, the tower was measured. In 1866-1867, the last in the XIX century large-scale reconstruction of the Kremlin fortress fortifications under the leadership of the palace architects Nikolay Shokhin , Fyodor Richter , Peter Gerasimov and others was carried out [52] . As a result of the restoration carried out by Gerasimov, the white-stone base of the tower was shifted, the architectural details of the two floors of the tower were repaired [53] . During the repair work, no sufficient architectural measurements and archaeological research were carried out [43] . In 1895, architect V.P. Zagorsky again repaired the walls and eaves of the Second Nameless Tower [54] .

20th century and modern times

During the revolutionary events in Moscow in October — November 1917, the Kremlin’s fortifications suffered. The Bolsheviks fired at walls and towers along the embankment of the Moskva River, as a result of which a shell struck one of the corners of the Second Anonymous Tower and hit the upper stone tent of the structure [55] . Restoration of the destroyed buildings of the Kremlin was carried out in 1919-1921 under the guidance of architects Ilya Bondarenko , Ivan Rylsky and Alexander Latkov [56] . Repair of the Second Nameless Tower was carried out as early as 1931-1935 [57] .

During the Moscow battles of 1942, German aircraft dropped a 50-kilogram high - explosive bomb into the Taynitsky Garden , located opposite the Second Nameless Tower [58] , and got into a car with ammunition. During the bombardment, 39 shells, 171 rifle cartridges and two trucks were destroyed, but the turret was not damaged during the shelling [59] .

In 1973–1981, a large-scale reconstruction of the Moscow Kremlin was re-designed by the architects A.V. Vorobiev and A.I. Khamtsov. The tower has been updated white-stone decor, dilapidated decorative parts replaced by copies [60] . Since December 1990, the Kremlin’s Second Nameless Tower, along with other Moscow Kremlin sites, has been on UNESCO’s cultural heritage list [57] .

In August 2017, the Moscow Kremlin commandant Sergey Khlebnikov announced another upcoming restoration of the Kremlin buildings - the fortress walls and towers should be put in order by 2020. Particular attention will be paid to the repair of gutters , waterproofing and wall cladding [61] .

Architectural Features

The second anonymous tower is deaf and has four floors. The base of the tower is a tetrahedron, and the top has the shape of a four-sided pyramid . The lower part is decorated with brick columns. The tent of the tower is covered with green tile [17] .

The inner space of the tower is formed by two tiers of rooms. The lower tier is characterized by a cylindrical vault , and the upper one has a vault that is closed with formwork. The top quadrangle is opened inside the tent, that is, there is no internal overlap between the quadrangle and the tent and one design changes into another [18] . The end of the tower is an octahedral tent with a weather vane [42] . The window of the second floor of the tower is made in the shape of a knee, a similar one was cut only in the Blagoveshchensk tower [62] . The vault of this floor was broken through, and an iron pipe comes out of it from the forge, which was once located on the lower floor [22] . According to Ivan Kondratyev , at the end of the 19th century, the tower no longer served as a defensive function and served as decoration of the Kremlin [63] .

Historian Sergey Bartenev used this to say about the tower: “[with] the dimensionality of its parts and architectural processing give it a look of friendliness and calm. By its slimness, it approaches the Armory Tower ” [64] .

In culture

- Like the First Nameless Tower, the Second is present in the picture of Konstantin Yuon “Old Moscow” [65] .

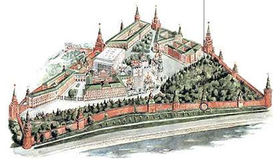

- The tower is depicted in the painting by Apollinari Vasnetsov “Moscow Kremlin. Cathedrals, 1894 [66] .

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 Guide, 1990 , p. 32.

- ↑ Second Nameless . Moscow Kremlin Museums. The appeal date is June 16, 2018.

- ↑ Goncharova, 1980 , p. 41

- ↑ Maria Besedina. Walking in pre-Peter Moscow . WikiRead (15-09-2012). The appeal date is June 15, 2018.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Malinovsky, 1992 , p. 15.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Dluzhnevskaya, 2006 , p. 18.

- ↑ Architectural Monuments, 1983 , p. 306-307.

- ↑ Goncharova, 1980 , p. 24

- ↑ All Moscow, 2011 , p. 401.

- ↑ Kostochkin, 1962 , p. 219.

- ↑ Goncharova, 1980 , p. 25

- ↑ Kostochkin, 1962 , p. 242.

- ↑ Universal History, 1968 , p. 54.

- ↑ Kiselev, 2006 .

- ↑ Belousova, 1997 .

- ↑ Belousova TM. Caches and underground structures of the ancient Kremlin . WikiRead. The appeal date is June 15, 2018.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Kolodny, 1983 , p. 94.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Architectural monuments, 1983 , p. 306.

- ↑ Bartenev, 1912 , p. 111.

- ↑ Goncharova, 1980 , p. 50.

- ↑ Viktorov, 1877 , p. 3

- ↑ 1 2 Bartenev, 1912 , p. 240

- ↑ Zemtsov, 1981 .

- ↑ Vorotnikova, Nedelin, 2013 , p. 144

- ↑ Goncharova, 1980 , p. 57.

- ↑ Architectural Monuments, 1983 , p. 300, 307.

- ↑ Romanyuk, 2013 , p. 65.

- ↑ Fabricius, 1883 , p. 216.

- ↑ Zabelin, 1990 , p. 169.

- ↑ Goncharova, 1980 , p. 58-60.

- ↑ Bartenev, 1912 , p. 68

- ↑ Vorotnikova, Nedelin, 2013 , p. 114

- ↑ Bartenev, 1912 , p. 69

- ↑ Architectural Monuments, 1983 , p. 300

- ↑ Zabelin, 1990 , p. 171.

- ↑ Architectural Monuments, 1983 , p. 285.

- ↑ Vorotnikova, Nedelin, 2013 , p. 141.

- ↑ Goncharova, 1980 , p. 61.

- ↑ Bartenev, 1912 , p. 74.

- ↑ Vorotnikova, Nedelin, 2013 , p. 145.

- ↑ 1 2 Goncharova, 1980 , p. 64.

- ↑ 1 2 Evdokimov, 2003 , p. 76.

- ↑ 1 2 Tikhomirova, 2012 , p. 252.

- ↑ Zabelin, 1990 , p. 176.

- ↑ Home life, 1990 , p. 131

- ↑ Tikhomirova, 2012 , p. 338.

- ↑ Bartenev, 1912 , p. 81.

- ↑ Bartenev, 1912 , p. 84

- ↑ Bartenev, 1912 , p. 85.

- ↑ Moscow shores: how the embankments in the capital have changed . RIA News (September 22, 2016). The appeal date is June 16, 2018.

- ↑ Tikhomirova, 2012 , p. 47

- ↑ Bartenev, 1912 , p. 87

- ↑ Tikhomirova, 2012 , p. 249, 346.

- ↑ Tikhomirova, 2012 , p. 348.

- ↑ Dmitry Abramov. The mission of Russia. World War I . iknigi.net. The appeal date is June 16, 2018.

- ↑ Tikhomirova, 2012 , p. 59.

- ↑ 1 2 Vorotnikova, Nedelin, 2013 , p. 167.

- ↑ Devyatov, Zhilyaev, Kaikova, 2010 , p. 88

- ↑ Yury Borisyonok, Sergey Devyatov, Valentin Zhilyaev, Olga Kaikova. The Kremlin was bombed eight times . WikiRead (May 1, 2017). The appeal date is June 15, 2018.

- ↑ A.S. Smagin. Study of the conservation and restoration of the Russian Kremlin Neopr . Scienceforum. The appeal date is June 16, 2018.

- ↑ Sergey Khlebnikov: the walls and towers of the Moscow Kremlin will be restored by 2020 . RIA News (August 25, 2017). The appeal date is June 16, 2018.

- ↑ Bartenev, 1912 , p. 237.

- ↑ Kondratiev, 1893 .

- ↑ Bartenev, 1912 , p. 238.

- ↑ Going to Moscow, 1997 .

- ↑ Moscow Kremlin. Cathedrals . ART-PORTAL. The appeal date is June 15, 2018.

Literature

- S. Bartenev. The Moscow Kremlin in antiquity and now .. - M .: Synodal Printing House, 1912. - V. 1. - 290 p.

- Belousova TM The Secrets of Underground Moscow . - M. , 1997.

- Viktor E. Viktorov. Inventory of dilapidations in the towers and walls of the Moscow Kremlin, the Chinese city and the White city of 1677 . - M. , 1877. - 16 p.

- Воротникова И. А., Неделин В. М. Кремли, крепости и укрепленные монастыри русского государства XV-XVII веков. Крепости Центральной России. — М. : БуксМАрт, 2013. — 887 с.

- Всеобщая история архитектуры в 12т. Т.VI Архитектура России, Украины и Белоруссии XIV - перв. floor. XIX вв.. — М. : Издательство литературы по строительству, 1968. — Т. VI. — 596 с. — 12 000 экз.

- Вострышев М. , Шокарев С. Вся Москва от А до Я. — М. : Энциклопедия, 2011. — 1064 с. - 3000 copies — ISBN 978-5-4320-0001-.

- Гончарова А. А. Стены и башни Кремля. — М. : Московский рабочий, 1980. — 96 с. - 50 000 copies

- Девятов С. В. , Жиляев В. И , Кайкова О.К. Московский Кремль в годы Великой Отечественной войны. — М. : Кучково поле, 2010. — 332 с.

- Длужневская Г. В. , Калинин В. А. , Субботин А. В. Кремли России XV-XVII вв.. — СПб: Литера, 2006. — 336 с. - 2500 copies — ISBN 5-94455-177-1 .

- Евдокимов Д. В. Кремль и Красная площадь. — М. : ИТРК, 2003. — 272 с. - 3000 copies — ISBN 5-88010-160-6 .

- Забелин И. Е. Домашний быт русских царей в XVI и XVII столетиях. Государев двор, или дворец. — М. : Книга, 1990. — Т. 1. — 312 с. - 100 000 copies — ISBN 5-212-00541-8 .

- Забелин И. Е. История города Москва. — М. : Столица, 1990. — 688 с. - 200 000 copies — ISBN 5-7055-0001-7 .

- Земцов С. М. Архитекторы Москвы второй половины XV и первой половины XVI века // Зодчие Москвы XV – XIX вв.. — М. , 1981.

- Киселёв А. Ю. Москва: Кремль и Красная площадь: путеводитель. — М. : АСТ, 2006.

- Кондратьев И. К. Седая старина Москвы . — М. , 1893.

- Колодный Л. Главный Кремль России. — М. : Сов. Россия, 1983. — 208 с. - 50 000 copies

- Колодный Л. Хождение в Москву . — М. : Голос, 1997. — 718 с.

- Косточкин В. В. Русское оборонное зодчество конца XIII - начала XVI веков . — М. : Издательство Академии наук, 1962. — 288 с. — 1400 экз.

- Либсон В. Я. , Домшлак М. И. , Аренкова Ю. И. и др. Кремль. Китай-город. Центральные площади. — М. : Искусство, 1983. — 504 с. — (Памятники архитектуры Москвы). - 25 000 copies

- Малиновский А. Ф. Обозрение Москвы. — М. : Московский рабочий, 1992. — 256 с. - 50 000 copies — ISBN 5-239-01340-3 .

- Романюк С. К. Сердце Москвы. От Кремля до Белого города. — М. : Центрполиграф, 2013. — 908 с. — (Москва и Подмосковье. История. Памятники. Судьбы). - 60 000 copies — ISBN 978-5-227-04778-6 .

- Московский Кремль. Guide. — М. : Московский рабочий, 1990. — 288 с. - 100 000 copies — ISBN 5-239-00780-2 .

- Слюнькова И. Н. Проекты оформления коронационных торжеств в России XIX века. — М. : БуксМАрт, 2013. — ISBN 978-5-906190-07-9 .

- Тихомирова А. Б. Архитектурная графика: Планы Московского Кремля и кремлевских садов, чертежи стен, башен и садовых построек. — М. : Полиформ, 2012. — 375 с. — (Каталог собрания Государственного историко-культурного музея-заповедника "Московский Кремль". Графика). - 1000 copies — ISBN 978-5-88678-194-6 .

- Фабрициус М. П. Кремль в Москве. Очерки и картины прошлого и настоящего. — Издание Т. И. Гаген, 1883. — 334 с.