The Icelandic sandpiper [1] ( lat. Calidris canutus ) is a bird of the snipe family ( Scolopacidae ).

| Icelandic Sandbox |

|

| Scientific classification |

|---|

| No rank : | Bilateral symmetrical |

| Suborder : | Scolopaci Stejneger , 1885 |

|

| International scientific name |

|---|

Calidris canutus ( Linnaeus , 1758 ) |

| Security status |

|---|

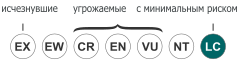

Least ConcernedIUCN 3.1 Least Concern : 22693363 |

|

Content

The Icelandic sandpiper is a compact bird with a short neck, its size is about 25 cm. The beak is relatively short and straight, brown-green legs are short. In the winter plumage, the upper side of this species is ash gray with light inclusions, the lower side is whitish with weak gray impregnations on the chest and sides. In the summer plumage of both sexes, the upper side is black with reddish splashes, the head and the lower side are painted in red-red color. In flight , the tail and white bordering of the wings are visible. Young birds resemble the winter plumage of adults in their appearance, but the upper side is brown with black and white spots and a dark strip in the middle, and the sides are beige. The legs are painted in olive green.

The Icelandic sandbox nests mainly in Greenland , Canada , Alaska and the Siberian tundra . His flights are extremely distant, and their goal is West Africa . On the way in spring and autumn, he rests in the Wadden Sea .

Nesting and migration of individual subspecies of the Icelandic sandbox

There are six subspecies of the Icelandic sandbox. Sorting from the largest to the smallest subspecies is presented here:

- C. c. roselaari

- C. c. rufa

- C. c. canutus

- C. c. islandica

- C. c. rogersi

- C. c. piersmai

C. c. piersmai nests in the north of Siberia and flies in the winter to the Yellow River Delta or to the northeast of Australia , where it hibernates on the muddy coasts. C. c. rogersi nests in the far north-east of Siberia and also migrates along the Chinese coast to the southeast of Australia, as well as to New Zealand . C. c. roselaari nests in the far north of Alaska and migrates through the Delaware Bay in the northeastern United States to Florida . It is not yet known whether this subspecies also flies along the western coast of the United States in order to winter in Central America . Subspecies C. c. rufa nests in the northwest of Canada, rests during a flight in like its relative in the Gulf of Delaware, and flies with stops in Brazil to Argentina . C. c. islandica nests in the north of Greenland and flies through Iceland and into Western Europe , where it hibernates on the expanses of the Wadden Sea. Nesting range of subspecies C. c. canutus is located in northwestern Siberia. He makes his migration to West Africa, where he hibernates on the muddy coasts. The Wadden Sea for this subspecies is an important stop during the flight.

Icelandic Sandboxes in the

Wadden Sea The food of the Icelandic sandbox consists mainly of bivalves and snails . It completely swallows the prey and crushes the hard shells with the help of the muscles of the stomach . In the nesting range, Icelandic sandboxes also eat land-based arthropods . When stopping on a migration path in the Bay of Delaware, they eat eggs from the shore clutches of horseshoe crabs.

Icelandic sandboxes nest in the vast Siberian tundra, Greenland, Canada and Alaska. They do not form colonies, but settle separately, sometimes at a distance of several kilometers from each other. The female lays 3-4 eggs in a hole in the ground lined with moss . Both parents incubate eggs , but the female leaves the nest shortly before the chicks are born. Chicks quickly get out of the nest and feed on their own from the first day. As soon as they gain the ability to fly, the male goes for the winter to the southern regions. Nestlings follow south in a few days or weeks unaccompanied by adults.

Icelandic sandbox in winter plumage

The Icelandic sandbox belongs to the species of birds that make the most distant flights without stops. These distances sometimes reach 5,000 km. To accomplish such an achievement, the Icelandic sandbox developed special attributes and abilities. Before a long flight, they take large amounts of food, almost double their normal weight. Over the whole body, they form fat deposits that supply them with energy during a long non-stop flight. To avoid excessive ballast and fat, the Icelandic sandboxes even reduce some internal organs, in particular the stomach. This change is caused by the food that Icelandic sandboxes take. Eating prey with hard shells leads to an increase in the stomach due to the training of muscles that crush them, while soft foods, such as worms , lead to a decrease in stomach and weight.

- ↑ Boehme R. L. , Flint V. E. The Bilingual Dictionary of Animal Names. Birds. Latin, Russian, English, German, French / Ed. ed. Acad. V. E. Sokolova . - M .: Rus. lang., "RUSSO", 1994. - S. 83. - 2030 copies. - ISBN 5-200-00643-0 .

- Piersma, T., de Goeij, TP & Tulp, I. 1993 An evaluation of intertidal feeding habitats from a shorebird perspective: towards relevant comparisons between temperate and tropical mudflats. Netherlands Journal of Sea Research 31, 503-512.

- Piersma, T., Dietz, MW, Dekinga, A., Nebel, S., van Gils, JA, Battley, PF & Spaans, B. 1999 Reversible size-changes in stomachs of shorebirds: when, to what extent, and why ? Acta Ornithologia 34, 175-181.

- Tomkovich, PS 2001 A new subspecies of Red Knot Calidris canutus from the New Siberian Islands. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists Club 121, 257-263.

- Tulp, I., Schekkerman, H., Piersma, T., Jukema, J., de Goeij, P. & van de Kam, J. 1998 Breeding waders at Cape Sterlegova, northern Taimyr, in 1994. Zeist: WIWO - Report 61.