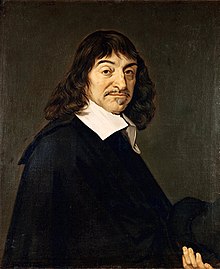

Cōgitō ergō sum [ˈkoːɡɪtoː ˈɛrɡoː sũ] (from lat. - “I think, therefore, I am ” [ sic ] [1] , the more common translation - “I think, therefore, I exist ” - is not accurate [2] ) - the philosophical statement of Rene Descartes , a fundamental element of Western rationalism of the New Age .

Descartes put forward this statement as primary authenticity, a truth that cannot be doubted - and with which, therefore, one can begin to rebuild the building of reliable knowledge.

The argument should not be understood as an inference [3] (“the one who thinks exists; I think; therefore, I exist”); on the contrary, its essence lies in the obviousness, self-confidence of my existence as a thinking subject ( res cogitans - “things thinking”): every act of thinking (and wider - every representation, experience of consciousness, because the cogito is not limited to thinking) is detected - with a reflective look at it - me, the thinker carrying out this act. The argument indicates the self-discovery of the subject in the act of thinking (consciousness): I think - and contemplating my thinking, I find myself thinking, behind its acts and contents.

Wording Options

Cogito ergo sum is a Latin translation of the statement of Descartes Je pense, donc je suis ( “I think, therefore, I am” ) [1] , which appears in his “Discourse on Method” (1637), written in French.

The phrase “Cogito ergo sum” is not used in Descartes' most significant work, “ Reflections on the First Philosophy ” [1] (1641), although this formulation is often mistakenly cited as an argument, referring to this work. Descartes feared that this formulation, which he had used in an earlier work, could be interpreted differently from the context in which he used it in his conclusions. [4] In an effort to get away from the wording that creates the appearance of a logical conclusion, while self-evidence is implied, the direct discretion of the affirmed truth, Descartes gets rid of the first part of the phrase and leaves only “I am” (“I exist”) : “every time I pronounce the words I am, I exist or perceive this saying with the mind, it will necessarily be true ”(Meditation II).

In the familiar form of Ego cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore, I am”), the argument appears in a later work of the Beginning of Philosophy (1644) written in Latin: “ Ac proinde haec cognitio, ego cogito, ergo sum, est omnium prima et certissima ... ”(§ 7).

A more complete version is formulated by Antoine Leonard Thoma : “Dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum” (“I doubt, therefore, I think, and therefore I am.”) This phrase is often mistakenly attributed to Descartes himself. [5] [6]

Augustine: Descartes' predecessor

Long before Descartes, a similar argument was offered in a polemic with skeptics by Augustine the Blessed in the book “ On the City of God ” (Prince XI, 26): Si fallor, sum (“If I am mistaken, I am”) .

However, the essential difference between Augustine and Descartes lies in the context, purpose, and consequences of the argument.

Augustine begins with the statement that, looking into our own souls, we “in ourselves recognize the image of God ... For we both exist, and we know that we exist, and we love this being and knowledge,” which corresponds to the threefold nature of God . Further, Augustine writes:

| I am not afraid of any objections from these academics to these truths, which might say: “What if you are being deceived?” If I am being deceived, then I already exist. For he who does not exist cannot, of course, be deceived: I, therefore, exist if I am deceived. |

Augustine, looking into his soul with faith , comes as a result of applying the argument to God; Descartes looks into his soul with doubt - and comes to the subject, consciousness, res cogitans (thinking substance), the requirement of which is clarity and distinctness. “While Augustine’s cogito pacifies, transforming everything in God, Descartes’s cogito problems everything else, in the sense that after gaining the truth of one’s own existence, one must turn to conquering a reality different from our“ I ”, constantly striving for clarity and distinctness ". [7]

Descartes himself spoke out about the differences between his and the Augustinian argument in response to a letter from Andreas Colvius.

Parallels in Hinduism

According to the Russian indologist S. V. Lobanov, Descartes’s idea of affirming “сogito, ergo sum” is one of the fundamental for the monistic systems of Indian philosophy - Advaita-Vedanta Shankara and para-Advaita, or Kashmiri Shaivism , the most prominent representative of which was Abkhinavagupta :

| René Descartes’s famous philosophical statement “ сogito, ergo sum ”, which became the starting point of Western rationalism and the philosophy of the New Age, was put forward by him as the primary certainty, with respect to which reliable knowledge can be built. Both Indian philosophers offer their solutions to the problem of self-discovery of the conscious subject, based on two different paradigms of philosophical monism. [eight] |

In popular culture

The phrase has been repeatedly quoted in literary works, in the media, and in the cartoon [9] :

“Cogito, ergo sumsum, ” one Maya buzzed in the morning ... “Cogito, ergo mus, ” Mickey Mouse repeated, and opened strawberry marmalade to lure the bee.

Original text (German)"Cogito, ergo sumsum", summte eines Morgens die Biene Maya [...] "Cogito, ergo mus", erwiderte Mickymaus und machte die Erdbeermarmelade auf, um das Bienchen anzulocken.- Wolfgang Mieder. "Cogito, ergo sum" ... - see snippet .

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 Motroshilova, N.V. Phenomena of memory of death and love in “Lectures on Proust” // Produced and named. - M., 1998. - Cit. : “The Cartesian cogito - I think, therefore, I am, is transformed into a slightly different, more extensive formula: suffering and loving, I remember and, therefore, I am, and therefore, there is, there is not only visible, but also invisible, intelligible world. "

- ↑ Lupandin, I.V. Descartes / I.V. Lupandin // Jacob Krotov Library. - Cit. : “Then about existence. Descartes says “I am” ([ego] sum), but deep down he understands that it would be more correct to say “I exist”, as in the Russian inaccurate (!) Translation. That is, one would have to say: “Cogito, ergo existo“ ”.

- ↑ For this, see, for example: Heidegger M. European nihilism . Ch. Cartesian cogito sum. - There is, however, an opposite interpretation based on the passage of § 10 “The Beginning of Philosophy” (see, for example: Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Descartes - The Cogito Argument Archived February 22, 2009. (Eng.) )

- ↑ After 300 years, Heidegger finds Descartes’s fears well-founded: “The biggest obstacle to the correct understanding of the thesis is the formula that Descartes introduced him to. Because of it - because of ergo ("hence") - it seems that the thesis is an inference that in its entirety is built up from a larger, smaller premise and conclusion "( Heidegger M. European nihilism . Ch." Cartesian cogito sum " )

- ↑ Ildikó Limpár. Displacing the Anxieties of Our World: Spaces of the Imagination . - Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017 .-- 228 p.

- ↑ Policing Literary Theory . - Brill Publishers, 2018 .-- 228 p.

- ↑ Reale J., Antiseri D. Western Philosophy from Origins to the Present. T. 3.- SPb., 1996.- S. 199.

- ↑ Sergey Lobanov . Cogito ergo sum in perspective of the monistic philosophy of Shankara and Abhinavagupta. [ specify ]

- ↑ See, for example, Wolfgang Mieder . "Cogito, ergo sum" - Ich denke, also bin ich. Das Descartes-Zitat in Literatur, Medien und Karikaturen. - Wien : Praesens Verlag, 2006 .-- ISBN 978-3-7069-0398-1 .

Literature

- Heidegger M. European nihilism . Chapters “Cogito Descartes as cogito me cogitare” and “Cartesian cogito sum”.

- Husserl E. Ideas for pure phenomenology and phenomenological philosophy. T. 1. - M .: DIK, 1999. § 46.

Links

See also

- Volo ergo sum