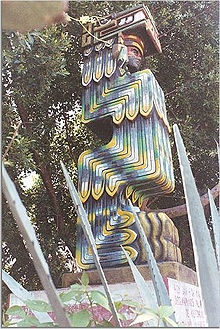

Quetzalcoatl (Quetzalcoatl, Quetzalcoatl, ast. Quetzalcōātl - “feathered serpent”; Spanish: Quetzalcóatl ; [ketsaɬˈko.aːtɬ] ) - the name of the deity of ancient America in the Nahuatl language, one of the main gods of the Aztec pantheon and other pantheon and historical person.

| Quetzalcoatl | |

|---|---|

| Mythology | Aztec mythology |

| Name interpretation | "Feathered serpent" |

| Latin spelling | Quetzalcōātl |

| Name in other languages | Kukulkan or Kukumats |

| Floor | male |

| Functions | personified the fertility of the earth |

| Father | |

| Mother | Chimalma |

| Brothers and sisters | , and |

| Related concepts | Quetzalcoatl (animal) |

| Symbol | snake venus |

| Mentions | Codex Borgia |

| Identifications | Ehecatl |

Quetzalcoatl is considered the son of the goddess Cimalma (Cimalmu). According to one legend, she conceived Quetzalcoatl, swallowing a jewel of greed [1] . Quetzal (quetzal, quetzal, quesal) is a small bird with a bright emerald plumage, which was highly appreciated in the traditional cultures of America. Quetzal is an ancient symbol of freedom: this bird does not live in captivity. In addition, in honor of the Aztec god, Quetzalcoatlus ( Latin Quetzalcoatlus ) got its name - probably the largest representative of both the pterosaur squad and flying animals in the entire history of the planet.

Content

Origin

The roots of the cult of the Serpent in Mesoamerica go back to ancient times; the first images of bird-like snakes date from the period 1150-500 BC. e. The snake personified the earth and vegetation, but for the first time snakes were depicted with quetzal feathers in Teotihuacan about 150 BC. e. More detailed images are found in the temple of Quetzalcoatl, built about 200 BC. e., on which you can see a rattlesnake with long green quetzal feathers.

In Teotihuacan, they worshiped Tlaloc , the god of water, while Quetzalcoatl, like a snake, personified the fertility of the earth and was subordinate to Tlaloc . After the development of the cult, he became independent. Over time, Quetzalcoatl merged with other deities and adopted their properties. Quetzalcoatl was often associated with Ehekatl ( Eekatl ), the god of air, personifying the forces of nature, and also associated with the "Morning Star" ( Venus ) (under the name Tlauiscalpantecutli (Tlauitskalpantecutli), Spanish. Tlahuixcalpantecuhtli ). The twin (nahual, nagual) and the twin of Quetzalcoatl Sholotl - the god of the evening star, the planet Venus. At night, he redirects the solar disk through the depths of the underworld from west to east. Quetzalcoatl became the embodiment of rain, divine waters and winds, while Tlaloc was the god of underground and lake waters, caves and rivers, as well as plants. Quetzalcoatl became one of the creator gods.

The influence of the god Teotihuacan spread to the Mayans , who called him Kukulkan (among the Yucatec Mayans) or Kukumats (from the mountain Mayans (quiche) ) - these names also mean "Feathered Serpent".

Historical Persons

In Shochikalko (700-900 CE) the rulers began to associate their power with the name of Quetzalcoatl, the images of God acquired more human features. Over time, the Toltecs adopted the religion, and their rulers began to use the name of Quetzalcoatl. The Toltecs portrayed the Feathered God as a man with divine traits that are also associated with their rulers. The most famous of these rulers was Se-Akatl Nakshitl Topiltsin Quetzalcoatl ( Nahuatl - One Reed Our Lord the Feathered Serpent ) (923–47 or 947–1000s), the legends of which are practically inseparable from the legends of God. Currently, the most recognized date of the appearance of Quetzalcoatl in Tula (Tollan) is the 980th year.

According to legend, Quetzalcoatl ruled in Tula for over 20 years. The great ruler taught the people mathematics , medicine , astronomy , writing , jewelry, weaving . His name was associated with the invention of a chocolate drink, the introduction of a calendar with a cycle of 52 years, the invention of the canons of music and dance. His syncretic and pacifist doctrine of "Toltecoyotl" ("Toltec spirit") provided for the prohibition of human sacrifice, which was categorically not accepted by the priestly elite. To ease dissatisfaction with the lack of previous bloody rituals, the ruler of Tollan made public bloodletting of his own blood from wounds from agave injections. Quetzalcoatl himself influenced his compatriots by personal example: he led an ascetic way of life, did not shun physical labor, did not drink intoxicating drinks, and maintained chastity.

Transformations of Xie Akatl Topiltsin Quetzalcoatl met with resistance from conservative priests of traditional cults, who achieved his expulsion from Tula. According to tradition, this departure occurred through the fault of those who wished (unlike the great ruler) to introduce obligatory human sacrifices to the priests of Witsilopochtli , Titlacauan and Tlacaupan . They took advantage of the fact that Quetzalcoatl was ill and offered him a stupefying “medicine” - an octally alcoholic drink. Having accepted it, he became distraught and had sexual intercourse with his sister Quetzaltepetl [2] .

According to one of the prevailing legends, he threw himself into a fire and turned into the "Morning Star" - Venus . The more popular version claims that Quetzalcoatl reached the coast of “divine waters” (the modern Gulf of Mexico ), where he built a “snake raft” and went east, to the “center of the sea”. After living in Cholula for twenty years, he led his comrades-in-arms, who found it dangerous to stay in the territory controlled by the Toltecs, on the land where the Yucatan Peninsula is guessed, where the classical Mayan civilization lived out its last days. The Toltec invasion of the peninsula is also known from Mayan information; The Toltec leader could be Topilzin Quetzalcoatl or one of his associates. According to Bartolome de Las Casas , all twenty Toltec leaders obeyed the leader Cuculcan, whom Diego de Landa describes as a man "good-natured, without a wife and children, revered after his exodus from Mexico as a god."

The last ruler of Tula, being in a difficult foreign policy position, also took the name of Quetzalcoatl; the destruction of the city by the chichimecs in 1116 or 1174 (The Seven Rabbit) was the end of his reign. The Toltecs connected Quetzalcoatl with their own god, Tezcatlipoca ( Tescatlipoca ), and made them equal rivals and twins. One of the legends about Se Akatla says that he considered his face so ugly that he released his long beard to hide it, and later began to wear a white mask. The legend was somewhat distorted, and in the images of Quetzalcoatl they often began to portray a white-bearded man.

Cult

The worship of Quetzalcoatl initially opposed human sacrifices and included the sacrifice of butterflies and hummingbirds. Only in the late period of the cult (when the influence of Quetzalcoatl as a politician came to naught) people were sacrificed.

Among the Toltecs, the enemy of the Feathered Serpent was Tescatlipoca , who sent Quetzalcoatl into exile. According to another version, Quetzalcoatl voluntarily sailed on a raft of snakes, promising to return. The widespread (especially in foreign literature) version of the identification by the Aztecs of Cortes with the returning god Quetzalcoatl, according to V. I. Gulyaev, is incorrect [3] .

When the Aztecs adopted the Toltec culture, Tescatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl became equal rivals; Quetzalcoatl was also called White Tescatlipoca, as opposed to Black Tescatlipoca . Together they created the world, with Tescatlipoca losing his foot.

Upon arrival in the new lands of Hernan Cortes in 1519, the Indians believed that the offended ruler had descended for the second time. The main attributes of Europeans prompted this idea: appearance (the presence of a beard worn by Quetzalcoatl, as well as a white skin tone), unknown animals ( horses ). Cortes used this legend to conquer the Aztecs.

See also

- Aztecs

- Kukulkan

- The Legend of Quetzalcoatl Cuculcan

Notes

- ↑ John Bierhorst: History and Mythology of the Aztecs; the Codex Chimalpopoca . University of Arizona Press, Arizona, 1992, p. 28.

- ↑ Codice Chimalpopoca: Anales de Cuauhtitlan y Leyenda de los Soles // Ed. F. Velazquez. Mexico, 1945. Fol. 75-76.

- ↑ For more on this, see: V. Gulyaev. And How many times have America been discovered? M., Knowledge, 1978, p. 22-27; Gulyaev V.I.In the footsteps of the conquistadors. M., Science, 1976, p. 46-49.

Literature

- Kinzhalov R.V. Quetzalcoatl // Mythological Dictionary / Ch. ed. E. M. Meletinsky . - M .: Soviet Encyclopedia , 1990 .-- 672 p.

- For historical Quetzalcoatl, see: Demetrio Sodi, The Great Cultures of Mesoamerica

- Boone, Elizabeth Hill. Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe. - Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society , 1989 .-- ISBN 0-87169-792-0 .

- Burkhart, Louise M. Holy Wednesday: A Nahua Drama from Early Colonial Mexico. - Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press , 1996 .-- ISBN 0-8122-1576-1 .

- Carrasco, David. Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of Empire: Myths and Prophecies in the Aztec Tradition. - Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press , 1982. - ISBN 0-226-09487-1 .

- Florescano, Enrique. The Myth of Quetzalcoatl. - translation of El mito de Quetzalcóatl original Spanish-language. - Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press , 1999. - ISBN 0-8018-7101-8 .

- Gardner, Brant . The Christianization of Quetzalcoatl (Neopr.) // Sunstone . - 1986.- T. 10 .

- Gillespie, Susan D. The Aztec Kings: The Construction of Rulership in Mexica History. - Tucson: University of Arizona Press , 1989 .-- ISBN 0-8165-1095-4 .

- Hodges, Blair Method and Skepticism (and Quetzalcoatl ...) (link not available) . Life on Gold Plates (September 29, 2008). Archived on April 9, 2012.

- James, Susan E. Some Aspects of the Aztec Religion in the Hopi Kachina Cult (English) // Journal of the Southwest : journal. - Tucson: University of Arizona Press . - Vol. 42 , no. 4 . - P. 897–926 . - ISSN 0894-8410 .

- Knight, Alan. Mexico: From the Beginning to the Spanish Conquest. - pbk. - Cambridge: Cambridge University Press , 2002. - ISBN 0-521-89195-7 .

- Lafaye, Jacques. Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe: The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness, 1531–1813. - Chicago: University of Chicago Press , 1987 .-- ISBN 0-226-46788-0 .

- Lawrence, DH The Plumed Serpent . - 1925.

- Locke, Raymond Friday. The Book of the Navajo. - Hollaway House, 2001.

- We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico / Lockhart, James . - Berkeley: University of California Press , 1993. - ISBN 0-520-07875-6 . (English) (Spanish)

- Martínez, Jose Luis. Gerónimo de Mendieta (1980) (neopr.) // Estudios de Cultura Nahuatl. - 1980 .-- T. 14 .

- Nicholson, HB Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl: the once and future lord of the Toltecs. - University Press of Colorado , 2001. - ISBN 0-87081-547-4 .

- Nicholson, HB The "Return of Quetzalcoatl": did it play a role in the conquest of Mexico ?. - Lancaster, CA: Labyrinthos, 2001.

- Phelan, John Leddy. The Millennial Kingdom of the Franciscans in the New World. - University of California Press , 1970.

- Pohl, John MD Creation Stories, Hero Cults, and Alliance Building: Postclassic Confederacies of Central and Southern Mexico from AD 1150–1458. In: The Postclassic Mesoamerican World. pp. 61–66. Edited by Michael Smith and Frances Berdan .. - University of Utah Press. , 2003.

- Pohl, John MD, Virginia M. Fields, and Victoria L. Lyall. Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico: Introduction. In: Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico. pp. 15–49 .. - Scala Publishers Ltd. , 2012.

- Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest . - Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press , 2003 .-- ISBN 0-19-516077-0 .

- Restall, Matthew . Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl: The Once and Future Lord of the Toltecs (review ) // Hispanic American Historical Review : journal. - 2003. - Vol. 83 , no. 4 .

- Ringle, William M .; Tomás Gallareta Negrón and George J. Bey. The Return of Quetzalcoatl (neopr.) // Ancient Mesoamerica. - Cambridge University Press, 1998. - T. 9 , No. 2 . - S. 183-232 . - DOI : 10.1017 / S0956536100001954 .

- Smith, Michael E. The Aztecs. - 2nd. - Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing , 2003 .-- ISBN 0-631-23015-7 .

- Taylor, John. An Examination into and an Elucidation of the Great Principle of the Mediation and Atonement of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ . - Deseret News , 1892.

- Townsend, Camilla. No one said it was Quetzalcoatl: Listening to the Indians in the conquest of Mexico (English) // History Compass : journal. - 2003. - Vol. 1 , no. 1 .

- Townsend, Camilla. Burying the White Gods: New perspectives on the Conquest of Mexico // The American Historical Review : journal. - 2003. - Vol. 108 , no. 3 .

- Wirth, Diane E. Quetzalcoatl, the Maya maize god and Jesus Christ (Neopr.) // Journal of Book of Mormon Studies . - Provo, Utah: Maxwell Institute , 2002. - T. 11 , No. 1 . - S. 4-15 . Archived February 17, 2009.

Original

- Presbyter Juan; Antonio Perez; fry Pedro de los Rios (glosses) . Codex Telluriano-Remensis . www.kuprienko.info. - Ukraine, Kiev, 2010. Translation from Spanish - A. Skromnitsky, V. Talah. Date of treatment November 11, 2012. Archived December 5, 2012.

- Tales of the Suns. Myths and historical legends of Nahua / Ed. and per. S.A. Kuprienko, V.N. Talah .. - K .: Vidavets Kuprіnko S.A., 2014 .-- 377 p. - ISBN 978-617-7085-11-8 .

- Alva Ishtlilshochitl, Fernando de . The history of the Chichimec people, their settlement and justification in the country of Anahuak. . www.kuprienko.info (March 22, 2010). - Per. with Spanish - V. Talah, Ukraine, Kiev, 2010. Date of treatment March 23, 2010. Archived August 23, 2011.

Links

- Mesoamerica through the eyes of Russian pioneers

- Ancient Mesoamerica

- "Encyclopedia" Myths of the World "": Quetzalcoatl

- Brent Gardner The Fathers of Quetzalcoatl (A Critical Study of Sources. Albuquerque, New Mexico. 1997)

- R.V. Kinzhalov (MAE RAS) Katabasis of Quetzalcoatl