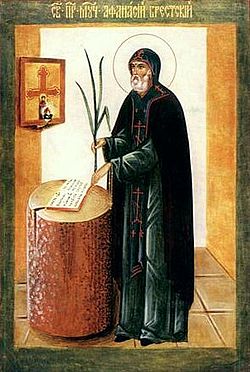

Athanasius of Brest (in the world bore the last name or patronymic of Filippovich ; c. 1595 [2] [1] , Brest region - September 5 [ September 15 ] 1648 [2] [1] [3] [4] ) - the holy Russian Orthodox Church , known public figure, writer, polemicist of the XVII century, composer [5] . An ardent opponent of the decisions of the Brest Cathedral in 1596 [6] .

| Athanasius of Brest | |

|---|---|

| |

| Name in the world | is unknown |

| Birth | OK. 1595 [1] |

| Death | September 5 (15), 1648 Brest |

| Is revered | in the Russian Orthodox Church |

| In the face | Martyrs |

| Day of Remembrance | September 5 (18) July 20 ( August 2 ) |

| Proceedings | “ Diariush ” (autobiographical composition) |

| Asceticism | fight against uniates |

He is the author of “ Diariush ” (“Diariush, Albo List of True Truths”) - one of the first literary works of the autobiographical genre and the only polemic autobiography in Belarusian literature [7] . Afanasy Filippovich is considered one of the last representatives of the Orthodox movement in polemic literature of the time [8] , whose works contain interesting information on the modern author of the church history of the Belarusian lands [9] .

The memory of Athanasius of Brest by the Orthodox Church is celebrated several times a year: September 5 (18) (day of death), July 20 ( August 2 ) - on the day of finding the relics [2] , as well as on the day of the Council of Belarusian Saints (3rd Sunday at Pentecost ) [10] .

Biography

The early years

There are no exact data on the life of Athanasius Filippovich until 1627. So, the exact date of birth of Athanasius is unknown; dating ranges between 1595 and 1600 [11] [12] . In their turn, researchers N. Petrov and M. Zhuk cite the year 1597 as the date of birth, based, in particular, on the author’s report from Diariush about his tonsure as a monk in 1627. The latter in the XVII century, according to the statutory rule in the Orthodox Church was allowed only after reaching 30 years. As an additional argument, the authors point out that only a person over twenty years of age could serve in the court of the nobility . According to the same Diariush, until 1620 Filippovich already had such a position [5] .

His place of birth is also unknown. It is believed that Athanasius was born in the western part of Belarus [13] : for example, some researchers believe that he was born in the Brest region [14] , others in the Grodno region [15] . However, the fact that Afanasy Filippovich was hegumen of the Brest St. Simeonovsky monastery , speaks of his origin from Brest region, since, according to church rules of the XVII century, such a large post as the abbot of the monastery could occupy, with rare exceptions, only a person born on this the earth [12] . This opinion is also confirmed by the lines from the epitaph on his death: “slaughtered // In the Birch bark of Lithuania, at his homeland” [16] . There is also no data on the worldly name of Athanasius, nor on what the name Filippovich is - a middle name or a surname. A. A. Melnikov considers the latter more likely, since the monastic name Athanasius is incompatible with his patronymic, while the priest often calls himself "humble Athanasius Filippovich." A similar combination of a spiritual name with a family name was customary at that time [11] . According to M. Petrov and N. Zhuk, in such sources as “Historical Documents of the Minsk Province and the Lithuanian Orthodox Diocese”, quite a few persons belonging to the nobility and the clergy carry the surname “Filippovich” [5] .

There are two versions of the social origin of Athanasius Filippovich. So, N.I. Kostomarov believed that Afanasy Filippovich came from a family of a poor gentry, as he served at the court of the hetman Lev Sapega as a home teacher, which, in his opinion, could only come from the gentry [17] . A. A. Melnikov [11] , A. A. Titovets [1] , N. Petrov with M. Zhuk [5], and K. I. Tarasov, who believed that a person without a noble title would not be invited to home teachers to the "prince" [18] . On the other hand, Athanasius himself in his "Diariush" emphasizes that he is "a nenzi man, a simpleton, a garbarchik" [19] . Proceeding from this, the Belarusian literary critic A. F. Korshunov believes that Athanasius came from a family of the urban artisan- tanner (Melnikov also allows this [11] ) [7] . However, these words could be spoken in accordance with the convictions of a monk, who, wishing to show the greatness of God and the Orthodox Church and to show his citizenship and respect for the king, had to emphasize his “lack of knowledge” (“poverty”, “poverty”) [7 ] .

As a child, Athanasius received a pretty good education [1] , probably in the Vilnius fraternal school at the Holy Spirit Monastery [13] . Perhaps, after graduation, wanting to continue his education, he studied at the Vilna Jesuit College [12] [20] . He brilliantly mastered Polish , Latin , Greek , Church Slavonic languages [5] [13] . From his youth, he began to teach “in the sciences of the Church Russian” [21] , possibly in the homes of the Orthodox and Catholic Hats [20] .

From 1622 [Comm 1] to 1627, Athanasius Filippovich served at the court of Leo Sapieha , who invited him as the home teacher Jan Faustin Luba [2] [1] . The latter was introduced to Athanasius as “Dmitrovich” [13] , the Russian Tsarevich Ioann, who was allegedly the nephew of the Russian Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich (1557-1598) and at the same time the grandson of Ivan IV the Terrible from his son Dmitry and Marina Mnishek . This “Dmitrovich” himself was the son of one of the impostors of False Dmitry II, who acted in 1607-1610. In fact, Yan Faustin was the son of Demetrius-Mikhail Luba, a gentry from Podlachia , who was killed in Moscow during a rebellion against the militia of False Dmitry I ( False Dmitry II is sometimes indicated [5] ), and the woman Mary who died in custody [20] . According to another version, Dmitry Luba was killed during the Moscow campaign, being part of the troops of the crown hetman Zholkevsky [22] . Athanasius at first was sure that he was raising the heir to the Moscow throne, and saw his invitation to the court of Sapega as an act of victory for the Orthodox Church [23] . After some time, Athanasius, on the basis of a number of facts, guessed the origin of the “prince” and painfully experienced it [24] .

Monasticism

Soon Athanasius, "realizing the fallacy of the other world" ("having saponified the saponification of the other world"), left the service at the chancellor’s court and in 1627 retired to the Vilensky Holy Spirit Monastery , where he was tonsured a monk [2] [14] by Father Superior Joseph (Bobrikovich ) With the blessing of Joseph (Bobrikovich), Athanasius soon went to obedience to the Kuteinsky monastery near Orsha , and then to the Mezhigorsky monastery near Kiev [25] [1] . It was the mention in the Diariush of the inter-Igumen igumen Commentary and priest Samoil Boretsky, the brother of Kiev Metropolitan Job Boretsky , who helped to accurately date Athanasius's stay in this monastery in the 1627th year [26] . In 1632 he returned to Vilna , where he was elevated to the rank of hieromonk [25] .

In 1633, Afanasy Filippovich came to the Pinsk Duboysky Monastery [27] [28] , where he became deputy governor of the monastery, Leonty Shitik , and for three years waged a stubborn struggle for the monastery, but in 1636, through the efforts of Albrecht Stanislav Radziwill , an ardent supporter of Catholicism, the Orthodox were forcibly expelled from the monastery, and the monastery itself with all its buildings and lands was given to the Pins Jesuits [25] [27] . The fact of the taking of the monastery made a strong impression on Athanasius [29] . In this regard, Athanasius wrote, “how, being in a frenzy” [Comm 2] , he saw mysterious phenomena in the sky - “seven hellfires” [Comm 3] , and in the fifth fire - “hot anger” (“roast anger”) - three persons: the papal legate , King Sigismund Wazu and Chancellor Leo Sapiehu [21] . Trying to keep the monastery, Athanasius made a complaint to Vladislav IV [27] , where he described what had happened, but even after the document was signed by many Orthodox, positive changes did not take place [25] .

After Athanasius moves to the neighboring Kupyatitsky Vvedensky monastery to the abbot of the monastery Illarion Denisovich ; here Filippovich finds a friend in the person of monk Makarii Tokarevsky, who in 1637 brought a station wagon from Metropolitan Peter (Graves) with permission to collect yalmuzhny - donations for the restoration of the Kupyatitsky monastery church. In November 1637, with the blessing of the abbot of the monastery and the advice of the brethren, Athanasius went to collect donation data [25] [28] together with his novice Onisim Volkovitsky. In the evening, the day before departure, Filippovich in his cell heard the words: “The Tsar of Moscow will build me a church! Go to him! ” [30] Before the trip, during a prayer in the church porch, Athanasius saw an icon of the Mother of God in the window and heard a voice saying that she was coming with him; he was also visited by a vision of the deacon Nehemiah who had died before this [31] .

Under the guise of collecting alms, Athanasius went to Moscow through Slutsk and Orsha to seek protection of the Orthodox faith from the Russian Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich [28] [30] . In Slutsk Filippovich met an unexpected problem: he was deprived of a station wagon by archimandrite Samuel Shitik, since he did not have the right to collect alms in the territory not belonging to the Lutsk diocese . After the resolution of this conflict at the end of January 1638, Athanasius and his companion arrived in Kuteyno to the abbot Joel Trutsevich . The latter had connections among the well-known Russian clergy and thereby could help the monks in the transition to Muscovy, the border with which was under strict supervision because of the fugitive Cossacks . Having received letters of recommendation (“cards about himself”), Athanasius went to Kopys , Mogilyov , Shklov . The next stop was the Kuteinsky monastery; here his governor Joseph Surta advised Athanasius to move through Trubchevsk . On the way to the last Filippovich with a satellite, a whole series of troubles awaited: problems with crossing the Dnieper , robbery and beating at one of the inns , and in the end, Prince Trubetskoy did not give out passes in the city. During the forced return, Athanasius visited the Chovsky monastery , from where, on the advice of one of the elders, he went to the Novgorod-Seversky district, counting on the help of the governor Pyotr Pesechinsky: as a result, the traveler crossed the border near the village of Shepelevo. Soon, on the way to Moscow, Filippovich quarreled with his novice, who ceased to believe in the success of their mission [31] .

Upon arrival in Moscow, travelers stopped in Zamoskvorechye , on Bolshaya Ordynka . Since it was difficult to get an appointment with the Tsar without authority and documents about yourself [30] , here, in Moscow, in his first journalistic work, a special publication, “History of Traveling to Moscow” [14] , compiled in March 1638 years, he described the king of the purpose and history of his difficult journey (the latter outlined in the form of a diary) [32] . In a relational writing in a peculiar form, using original poetic techniques, the difficult situation in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth described the Orthodox inhabitants of Belarus and Ukraine [1] [14] [2] and begged to stand up for the latter [30] . Athanasius wanted to convince Mikhail Fedorovich to start a war with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to defend the Orthodox faith [14] , referring to the Virgin , who allegedly told him: “O Athanasius! Go to Tsar Michael and tell him: defeat our enemies, for the time has come ” [33] . In addition, Athanasius advised the Russian ruler to make an image on the banners of the Kupyatitsky Mother of God , whose image along with the note was transferred to the Tsar [34] . He also informed Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich about the preparation of False Dmitry [7] . Adopted at the Embassy's hut , Filippovich, among other things, reports the preparation of an impostor [30] . On a flowering Palm Sunday, Athanasius, collecting generous donations, left Moscow and returned to Vilna on June 16 (26), 1638 , and in July he returned to the Kupyatitsky Monastery [34] .

Monastery Fight

In 1640, Kupyatitsa received a petition from the brethren of the St. Simeon Monastery in Brest , which had lost its rector, to bless either Abanasy Filippovich or Makarii Tokarevsky as abbot, and Athanasius was elected for this post [34] [14] [28] . Then a new period began in his life: in Brest, Filippovich began to wage an active struggle against Uniate [7] . In order to protect the Orthodox churches from the attacks of the Uniates by Athanasius, six documents of the 15th century were discovered and entered into the city books of Magdeburg. These papers, relating to the Brest Nicholas fraternity, uniting the St. Simeonovsky monastery and the monastery of the Nativity of the Virgin, gave the right to legal registration of the rights of the Nativity of the Theotokos brotherhood. To this end, in September 1641, Athanasius arrives at the Warsaw Diet , where on October 13 he manages to obtain privileges in the Royal Chancellery , which confirmed the previous letters and rights of his brothers and gave permission to acquire land in Brest for the construction of a fraternal house [34] . However, Chancellor Albrecht Radziwill and Chancellor Trizna refused to ratify the document “even for thirty firm thalers”, referring to the Pope’s prohibition to further spread the Orthodox faith. Out of fears of new persecution, the Orthodox bishops gathered at the Sejm could not help Filippovich [35] .

In 1643, Athanasius Filippovich again arrives in Warsaw on the next shaft diet. At the same time as Deacon Leonty of God, who came with him, he entered the Senate and the Embassy Court on March 10, 1643 [35] . Interrupting the court case, which was attended by Polish King Wladyslaw IV , he distributes to the king and senators lists on the canvas of the Kupyatitsky Icon of the Mother of God with a warning inscription testifying to the oppression of the Orthodox in the Commonwealth [29] (the same was done by the deacon of God at the embassy court). Athanasius demanded that the king stop the persecution of the Orthodox and abolish the union [36] , otherwise threatening God's court. The next day, the king ordered the issuance of Orthodox privileges [7] .

For the deed of Athanasius, the highest church authorities declared him crazy and demanded to appear for trial, where they accused him of risking to come to the Sejm and to put forward ultimatum conditions on behalf of the whole Orthodox Church without their advice and permission [15] . Later Filippovich himself noted: “Already our fathers themselves, elders in the Orthodox faith, are not worried about the multiplication of God's praise” [Comm 4] [21] . The Orthodox hierarchs and rectors of large monasteries present at the Sejm were afraid of the consequences of harsh statements and the extraordinary behavior of Athanasius at the Sejm. Therefore, according to their order, the reverend was imprisoned together with his comrade-in-office deacon Leonty in the house of the royal gatekeeper Jan Zhelezovsky for several weeks until the end of the Sejm [35] . In response to this, on March 25 ( April 4 ), 1643 , at the celebration of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary , Athanasius escaped from captivity in a hood and paramanda , and, posing as a holy fool and pumped out in the mud, he ran like that, striking himself with a staff, all over Warsaw, shouting: “Trouble is damned and unfaithful! Vae maledictus et infidelibus! ” [7]

Soon Athanasius was again remanded in custody, and after the Sejm’s departure, he was brought to church court . It was decided to temporarily deprive him of priestly and hegumen dignity ("narrow, decreed, degraded from presbytery and abbess"); Filippovich was sent to Kiev [1] for the final hearing of the consistory . During his imprisonment, pending the arrival of the government prosecutor, he wrote in Latin “An Explanatory Note to the Court of the Spiritual Consistory” [35] [37] [14] . The court, chaired by the rector of the Kiev-Mohyla Academy, Innocent Gisel, ruled that Athanasius atoned for his misconduct by imprisonment and that, therefore, freedom should be granted to Athanasius and the priest's dignity should be restored. This decision was approved by the Metropolitan of Kiev Pyotr Mogila, who on June 20 sent Athanasius the head priest at the St. Simeon Monastery, transmitting a message advising him to be more restrained in matters of this kind [35] [7] .

Repeated Arrest and Journalism

Upon his return to the monastery, Athanasius lived “a considerable time in peace”, and then continued to apply for support for the Brest fraternity. In 1644, Filippovich, hoping for help on the letter of protection to help the Novogrudok governor Nikolai Sapieha, the patron of the St. Simeon Monastery, went to Krakow, collecting donations for the church along the way. However, the appeal was ultimately inconclusive [7] , and Filippovich turned to the Moscow ambassador, Prince Lvov, who investigated cases of impostors. During the meeting, Athanasius told the ambassador both about his trip to Moscow and about many facts from the life of Y. F. Luba, transmitting, among other things, one of his last messages, thereby providing the ambassador with the material evidence necessary to institute legal proceedings [38 ] .

Athanasius was summoned from Krakow to Warsaw by a letter from the Warsaw lawyer Zychevsky informing him on May 3, 1644, that through his efforts the letter given by Filippovich to assure the Chancellor was provided with all the necessary seals. The lawyer demanded to redeem the privilege for six thousand zlotys , however, upon arriving in Warsaw, Athanasius discovered that his privilege was not included in the royal metric and had no legal force, and refused to redeem it. Returning to Brest, Athanasius ordered a copy of the Kupyatitsky Icon of the Mother of God at the local Bernardine monastery and placed it in his cell. Inspired by the icon, Filippovich, in preparation for the 1645 Diet, took up the compilation of a new public complaint, creating several dozen handwritten copies of the “History of Traveling to Moscow” with the image of the Kupyatitskaya Icon [38] .

However, a few weeks before the Sejm in the summer of 1645 [Comm 5] in Brest, Athanasius was arrested as a “state criminal” [1] [14] and sent under escort to Warsaw; here he was to remain a hostage for Y. F. Lubu, taken to Moscow [39] [14] . A letter from a certain Mikhail testifies to daily interrogations and torture. The requests for release did not have a result, despite the fact that Luba was released on July 23 by the petitions of Ambassador Gabriel Stempkovsky. Having been imprisoned for about six months, Athanasius wrote a number of works: “Noviny” (with his own spiritual verse , put on his own music), “The Foundation for the disorder of the Rymsky church”, “Prepared for trial”, “Porada pozbozhna” [14] , “About the foundation ecclesiastical ”,“ Suplik III ”(“ Suplik III ”) (was filed by a supporter of Athanasius in the king’s carriage when he left [40] ), in which he expressed his views on the history of the Union of Brest and showed its perniciousness for Orthodoxy and the state of the Commonwealth . Then he compiled Pravda, addressed to Vladislav IV and submitted to him on June 29, 1645 [40] , where he proposed concrete ways of reconciling Catholicism and Orthodoxy , as well as improving life in the state. First of all, Athanasius advised to get rid of the influence of the Jesuits, to apply through letters to the five patriarchs of the Eastern Church and return to the Council the legal rights of Orthodoxy in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania [29] . Also, the works written by him while he was in a Warsaw prison and addressed to the king contain criticism of contemporary church hierarchs and secular magnates , as well as proposals for the revival of the Orthodox Church and the conclusion of an alliance with Russia [1] [14] . At the same time, Filippovich considered his arrest a political action and revenge for his struggle for the defense of Orthodoxy [14] .

Not succumbing to a provocation with a jailbreak, Athanasius waited for his release, especially after spreading the rumor that the king wanted to meet him in person. The rumors, however, did not materialize, but on November 3 ( November 13 ), 1645, according to the order of the royal universal, Filippovich, accompanied by a convoy, was sent to Kiev under the supervision of the Metropolitan of Kiev Peter (Graves), who left Filippovich in Kiev Pechersk Lavra [41] [ 42] . It was here that in 1646 Athanasius created the “Diariush” [3] in the form in which it was subsequently published: the author brought all of his works in one work, providing the early works with commentaries. Then Filippovich handed the work to Peter (Mogile) with the hope of liberation, but the latter did not materialize [43] .

On September 14, 1646, in the Pechersk Monastery Church Athanasius appeared in the form of a holy fool in order to recall his innocence. He explained the explanation of these actions in his last article - “The reasons for my deed in the church of St. Pechara-Kiev miraculous on the Exaltation of the Holy Cross to the Rock of 1646” [44] .

Third Arrest and Murder

After the death of Metropolitan Peter (Graves) on January 1, 1647, the Lutsk hierarch Afanasy Puzyna , who came to the burial of the Metropolitan, took Filippovich with him on departure and after asking the brethren allowed him to return to Brest, to the monastery. In connection with the uprising of Khmelnitsky in 1648, a new wave of persecution rose against the Orthodox [29] . According to the denunciation of the captain of the royal guard Shumsky [45] on Saturday , July 1 ( July 10 ), 1648 A. Filippovich was arrested immediately after the Divine Liturgy in the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin [41] on charges of cooperation with Bogdan Khmelnitsky [46] [2] , for “Sending some letters and gunpowder to the Cossacks” [Comm 6] [3] . In response to the accusations Athanasius demanded testimonies of the tax collectors : “Let them admit if I ever delivered gunpowder somewhere.” And the pages of letters, let me show some evidence for this, that they sent them as he tells them ” [Comm 7] [3] . Soon, a search was conducted in the Brest monastery, which, however, did not give positive results [47] .

Then they put the blame on Filippovich that “they blasphemed the holy union and cursed” [Comm. 8] . In response to the latest charge, Athanasius answered: “Your present union is cursed. And know for sure that if you don’t uproot it from your pampering, and you can’t calm the Eastern Orthodox Church, you will gain God's wrath over yourself ” [Comm 9] [3] . The judges ruled that Filippovich deserved the death penalty, but the latter required final sanction from Warsaw. Athanasius was temporarily chained to pads and thrown into the arsenal . On the night of September 5, shortly after Athanasius confirmed the union’s curse before the Lutsk bishop Gembitsky and Chancellor Albrecht Radziwill who arrived, a Jesuit student was sent to his cell, however, the latter’s attempts to persuade Athanasius to his side were unsuccessful [47] . Soon Filippovich, having previously removed the pads from him, was brought to the Brest governor A. Masalsky , who, not wanting to take him to himself, said: “Why did you bring him to me? He is already in your hands - so do what you want with him! ” [Comm 10] [47] [48] [3] Then A. Filippovich was taken out of the wagon train to the forest near the village of Gershanovichy and after torture (“ there he was first they tortured him with fire, and they said - they filled the musket with two bullets ... And they said they cooked the grave " [Comm 11] ), soldiers of the Brest voivode killed the priest [49] [14] . According to eyewitnesses, wounded two bullets in the forehead right through, stood for a while, leaning against a pine tree, until it was shoved into a dug grave [50] [21] . Before his death, he did not give up his words: “What I have said, I said, and I am dying with that” [Comm. 12] [49] [48] .

Only eight months later, on May 1, 1649, did a certain boy show the monks where the abbot’s grave was. 7 мая 1649 года с разрешения полковника Фелициана Тышкевича иноки перенесли его в свой монастырь и с почестями похоронили в склепике на правом клиросе в храме святого Симеона Столпника [51] [29] .

Личность и взгляды

Лейтмотивом жизни Афанасия Филипповича стала борьба с унией и за объединение православных народов [24] . Так, будучи ярым противником решений Брестского собора 1596 года, Афанасий считал, что обострение социальных и религиозных противоречий в государстве стало непосредственным проявлением последствий унии, которая затронула как светскую, так и духовную жизнь населения, привела к нарушениям общепринятых законов и попиранию прав народа [14] .

Будучи, таким образом, главной причиной разногласий в обществе и, по мнению автора, навязанной народу (а значит и незаконной), уния должна быть уничтожена. Однако в произведениях Филипповича не содержится призыва к насилию: автор, будучи хорошо подготовлен юридически, старается действовать в рамках правовой системы Речи Посполитой. Так, отлично знающий историю православной церкви вкупе с правовой базой, регулирующей её деятельность в государстве, он аргументированно выстраивает свои обвинения. Кроме того, рассматривая унию и её предысторию, Афанасий привлекает и цитаты из исторических хроник . По мнению мыслителя, необходимыми условиями возвращения мира в общество Речи Посполитой являются справедливость и неприкосновенность законных духовных интересов православных жителей. Всей полнотой законодательной власти должен обладать не кто иной, как король: именно последний сможет вернуть согласие в общество. Остальные же органы власти — сенат, синод и сейм — должны обладать лишь совещательной функцией, иначе шляхетская анархия в государстве продолжится. При этом светская власть должна претендовать лишь на земной мир, в то время как духовный остаётся ей неподвластным, в том числе и папе римскому [52] .

От прочих антиуниатских писателей-полемистов Филипповича отличало то, что в своих произведениях он старался не затрагивать церковно- догматического богословия. Данная особенность его творчества была основана на убеждении в том, что в основе стремления и польских феодалов, и католической церкви, заручившихся поддержкой некоторых православных иерархов, унифицировать оба вероисповедания лежали политические мотивы, а отнюдь не религиозные. Результатом стали не только критика униатской и католической церквей, но и обличение правящих шляхетско-магнатских кругов Речи Посполитой [14] [52] .

В свою очередь, в произведениях, написанных Афанасием Филипповичем в варшавской тюрьме, отразилась его упорная борьба за «грунтовное успокоение православного вероисповедания», за нормализацию отношений с Россией. Укрепление последних он обосновывал «волей Божией» и выступал против войны с этим государством [53] .

Creativity

Афанасий Брестский является автором « Диариуша » («Діаріушъ, албо списокъ дѣевъ правдивыхъ») — одного из первых литературных произведений автобиографического жанра и единственной полемической автобиографии в белорусской литературе .

В «Диариуше», ставшем одной из первых литературных произведений автобиографического жанра и единственной полемической автобиографией в белорусской литературе [7] , была объединена в одно целое вся публицистика автора (его дорожные и объяснительные записки, дневники, автобиографический очерк, различные легенды и мистические видения, послания и письма Афанасия, его обличительные речи, конспективные наброски отдельных статей, философско-богословские трактаты, стихи о борьбе [54] [12] ), а также был размещён напев гимноподобного канта. Последний представляет собой одну из наиболее ранних нотных записей в белорусской музыке , при этом сам напев записан киевской пятилинейной нотацией [2] [1] .

В число особенностей, позволяющих назвать «Диариуш» одним из ярких памятников полемической литературы XVII века, входят его идейная насыщенность, разнообразные и колоритные стилистические оттенки, богатство как повествовательных средств, так и художественных приёмов. Среди прочего, в этом произведении автором были отражены некоторые стороны борьбы белорусского народа за свои права и культуру, а также обычаи и традиции того времени [54] . Сам автор считает, что его произведение сохранит актуальность и позже, «у потомные часы» [52] .

Язык произведения — «сочный, красивый, милозвучный, язык белоруса, белоруса высокообразованного» ( белор. сакавітая, прыгожая, мілагучная, мова беларуса, беларуса высокаадукаванага ) [5] .

Сохранилось два списка «Диаруша» — один в составе Толковой Псалтири, принадлежавшей митрополиту Димитрию Ростовскому (хранится в ГИМ ), и менее полный список позднего происхождения из собрания РНБ [55] .

Honor

Афанасий Филиппович был признан святым вскоре после своей смерти (между 1658 и 1666 годами [2] [1] ). Уже 5 января 1658 года Киево-Печерский архимандрит Иннокентий Гизель и настоятель Лещинского монастыря игумен Иосиф Нелюбович-Тукальский сообщили царю Алексею Михайловичу , что над мощами Афанасия якобы неоднократно замечался чудесный свет. Вскоре в народе были сложены сказание о гибели Филипповича и церковное песнопение в его честь; 30 августа 1819 года архимандритом Маркианом были написаны кондак и тропарь святому. Время установления официального празднования святому неизвестно, однако Афанасия Брестского именует преподобным мучеником, причисленным к лику киевских святых, ещё святитель Георгий Конисский в своей «Истории об унии» [51] .

20 июля 1666 года мощи преподобномученика Афанасия были открыты. По этому поводу в Бресте было составлено «Житие» святого на польском языке , в котором игумен Афанасий называется «святым и преподобномучеником». В 1805 году в Киевской духовной академии «Житие» было переведено на русский язык [29] . Глава святого Афанасия по приказу императора Петра I была перенесена в Санкт-Петербург [55] . Сохранился также документ, рассказывающий о смерти Афанасия: «О смерти славной памяти небожчика отца Афанасіа Филиповича, ігумена берестейского православного, повесть през послушников его списана, року 1648 сталой, под час безкрулевья» [3] .

8 сентября 1815 года в результате пожара в Симеоновской церкви медная рака с мощами святого Афанасия расплавилась. После обнаружения на следующий день частиц мощей священник Самуил Лисовский положил их на оловянное блюдце под алтарём монастырской трапезной церкви. В 1823 году, когда состоялось принятие церковного имущества новым настоятелем Автономом, их подлинность засвидетельствовали присяжными показаниями семь жителей Бреста: они входили в число тех, кто участвовал после пожара в собирании частиц мощей. Вскоре по просьбе Автонома от Минского архиепископа Анатолия поступило распоряжение: «положить мощи в ковчег и хранить оные в церкви с благоприличием» [51] .

В ноябре 1856 года был засвидетельствован факт исцеления 10-летнего сына помещика Поливанова, вынужденного остановиться в Бресте из-за болезни ребёнка, у ковчега с мощами преподобного Афанасия, приписанный действию молитв ко святому. В 1857 году в благодарность за исцеление сына помещик пожертвовал для мощей драгоценный серебряный позолоченный ковчег (в 1894 году над ним была создана сень с изображением святого [56] ). После закрытия монастыря ковчег был перевезён в Антирелигиозный музей искусств, расположенный в Донском монастыре , а оттуда в 1935 году поступил в Государственный исторический музей России. К 14 мая 1860 года относится факт исцеления смертельно больного протоиерея Василия Соловьевича [56] .

26 сентября 1893 года в Гродненском Борисоглебском монастыре был воздвигнут храм во имя святого преподобномученика святого Афанасия Брестского (до наших дней не сохранился) [1] [51] . На рубеже XIX—XX веков в деревне Аркадия [Комм 13] под Брестом (сейчас территория города) в память об Афанасии Брестском, недалеко от места его гибели, была возведена деревянная каплица — Свято-Афанасьевская церковь [1] [57] со звонницей на главном фасаде [58] . Возведённая из соснового бруса на каменном цоколе и представляющая собой памятник народного деревянного зодчества [57] с чертами ретроспективно-русского стиля , церковь в 1998 году была обновлена силами прихожан [59] ; входит в Государственный список историко-культурных ценностей Республики Беларусь (категория № 3) [60] . Здесь же в 1996 году по благословению Священного Синода Русской православной церкви был основан Свято-Афанасьевский монастырь , в состав которого входит вышеназванная церковь [59] .

Осенью 1893 года частица его святых мощей была перенесена в Леснинский женский монастырь в Польше [61] . В конце Второй мировой войны монастырь (вместе с святыми мощами) переехал сначала в Сербию, а затем во Францию. В 1995 году часть мощей была привезена в Белоруссию и передана в брестские Свято-Симеоновский собор , Свято-Афанасьевскую церковь [62] и Свято-Николаевский храм .

С 1996 года Афанасий является святым покровителем Люблинской и Холмской епархии Польской православной церкви [63] .

16—18 сентября 1996 года в Бресте прошли торжественные мероприятия в честь преподобного великомученика Афанасия Филипповича; была проведена церковно-научная конференция, открыл которую Патриарший Экзарх всея Беларуси Митрополит Минский и Слуцкий Филарет (Вахромеев) [24] .

В 2006 году в Бресте на проспекте Машерова возле Свято-Симеоновского собора был воздвигнут памятник «небесному заступнику» Афанасию Брестскому работы скульптора Олеси Гурщенковой [64] .

Comments

- ↑ Иногда в качестве даты начала службы у Льва Сапеги называется 1620 год. См: Асветнікі зямлі Беларускай, X — пачатак XX ст. / Рэдкал.: Г. П. Пашкоў (гал. рэд.) і інш. - Mn. : БелЭн, 2001. — С. 450. — 496 с. — ISBN 985-11-0205-9 . ; Козел А. А. Философская мысль Беларуси. - Mn. : Амалфея, 2004. — С. 155. — 352 с. — ISBN 985-441-332-2 . .

- ↑ В оригинале — «как в захвиценю котором будучи».

- ↑ В оригинале — «седм огнов пекелных».

- ↑ В оригинале — «Юж-юж и сами отцеве наши старшии в вере православной о помноженю хвалы бозское не дбают».

- ↑ Иногда указывается 1644 год (см.: Цітавец А. А. Афанасій Брэсцкі // Рэлігія і царква на Беларусі: Энцыкл. давед. / рэдкал.: Г. П. Пашкоў і інш. — Мн. : БелЭн, 2001. — С. 26. — 368 с. — ISBN 985-11-0220-2 . ), октябрь (см. : Асветнікі зямлі Беларускай, X — пачатак XX ст. / Рэдкал.: Г. П. Пашкоў (гал. рэд.) і інш. — Мн. : БелЭн, 2001. — 496 с. — ISBN 985-11-0205-9 . ) или ноябрь этого года (см.: Козел А. А. Философская мысль Беларуси. — Мн. : Амалфея, 2004. — С. 158. — 352 с. — ISBN 985-441-332-2 . ).

- ↑ В оригинале — «посылане якихсь листов и порох до козаков».

- ↑ В оригинале — «Нехай они признают, если я коли колвек куды порохи проводил. А стороны листов, нехай ми тут довод який на тое покажет, абым их посылал, яко поведает».

- ↑ В оригинале — «унею святую ганил и проклинал».

- ↑ В оригинале — «Проклятая есть теперешняя унея ваша. И ведайте о том запевне, если еи з панства своего не выкорените, а православной церкви всходней не успокоите, гневу божого над собою заживете».

- ↑ В оригинале — «По що-сте его до мене привели? Маете юж в руках своих, чините ж собе з ним що хощете!».

- ↑ В оригинале — «там его напрод пекли огнём. И казали — мушкет набили двова кулями … И дол казали наготовили».

- ↑ В оригинале — «щомъ южъ реклъ, томъ реклъ и зъ тымъ умираю».

- ↑ Иногда указывается рядом расположенная деревня Гершоны, также включённая в 2006 году в состав Бреста. См.: Цітавец А. А. Афанасій Брэсцкі // Рэлігія і царква на Беларусі: Энцыкл. давед. / рэдкал.: Г. П. Пашкоў і інш. - Mn. : БелЭн, 2001. — С. 26. — 368 с. — ISBN 985-11-0220-2 . ; Кулагін А. М. Праваслаўныя храмы на Беларусі : энцыклапедычны даведнік. - Mn. : БелЭн, 2001. — С. 311. — 328 с. — ISBN 985-11-0190-7 . .

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Рэлігія, 2001 , с. 26.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Вялікае княства Літоўскае, 2007 , с. 267.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Петров, Жук, 1997 , с. 164.

- ↑ Славянамоўная паэзія Вялікага Княства Літоўскага XVI—XVIII стст. / Уклад., прадм. і камент. А. У. Бразгунова. — Минск: Белорусская наука, 2011. — 79 с. — ISBN 978—985-08-1291-9.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Петров, Жук, 1997 , с. 160.

- ↑ Гісторыя Беларусі / Рэдкал.: М. Касцюк (гал. рэд.) і інш. - Mn. : Экаперспектыва, 2007. — Т. 3: Беларусь у часы Рэчы Паспалітай (XVII–XVIII стст.). — С. 15. — 344 с. — ISBN 978-985-469-203-6 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Гісторыя беларускай літаратуры XI—XIX стагоддзяў у двух тамах. — Минск: Белорусская наука, 2006. — Т. 1. Даўняя літаратура XI — першай паловы XVIII стагоддзя. — С. 586—611.

- ↑ Гедзімін Л. А. V Международные Кирилло-Мефодиевские чтения, посвященные Дням славянской письменности и культуры: Материалы чтений (Минск, 24—26 мая 1999 г.). Ч. 1. — Минск: Европейский гуманитарный ун-т, Бел. университет культуры, 2000.

- ↑ Гісторыя Беларусі / Рэдкал.: М. Касцюк (гал. рэд.) і інш. - Mn. : Экаперспектыва, 2007. — Т. 3: Беларусь у часы Рэчы Паспалітай (XVII–XVIII стст.). — С. 22. — 344 с. — ISBN 978-985-469-203-6 .

- ↑ Афанасий (Филиппович), преподобномученик, игумен Брестского монастыря . Orthodox Encyclopedia. Дата обращения 29 декабря 2013.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Мельников, 1992 , с. 205.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 410 год з дня нараджэння Афанасія Брэсцкага (Філіповіча Афанасія; каля 1595 ці каля 1596 ці 1597(?) — 1648), святога беларускай праваслаўнай царквы, грамадскага, палітычага і царкоўнага дзеяча, пісьменніка-публіцыста. Нацыянальная бібліятэка Беларусі . Date of treatment October 22, 2013.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Козел, 2004 , с. 155.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Асветнікі, 2001 , с. 450.

- ↑ 1 2 Святлана Марозава. Филиппович Афанасий . belchrist.narod.ru. Date of treatment January 5, 2014.

- ↑ Коршунов, 1965 , с. 179.

- ↑ Костомаров Н. И. Афанасий Филиппович — борец за православную веру в Западной Руси // Исторические монографии и исследования. — СПб, 1881. — С. 1—42.

- ↑ Тарасов К. И. Памяць пра легенды: Постаці беларускай мінуўшчыны. — 1990. — С. 130. — 270 с.

- ↑ «Диариуш» Святого преподобномученика Афанасия Брестского (недоступная ссылка) . Дата обращения 22 октября 2013. Архивировано 23 октября 2013 года.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Мельников, 1992 , с. 206.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Чаропка В. Афанасій Філіповіч // Полымя. - 2002. - No. 1 . — С. 184—189 .

- ↑ Юзефович, 1999 , «Дети» царя Дмитрия, с. 63.

- ↑ Коршунов, 1965 , с. 29.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Петров, Жук, 1997 , с. 161.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Мельников, 1992 , с. 207.

- ↑ Коршунов, 1965 , с. 30.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Козел, 2004 , с. 156.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Петров, Жук, 1997 , с. 163.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Святы прападобнамучанік Афанасій Брэсцкі. blagobor.by . Date of treatment October 22, 2013.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Козел, 2004 , с. 157.

- ↑ 1 2 Мельников, 1992 , с. 208.

- ↑ Мельников, 1992 , с. 208—209.

- ↑ Коршунов, 1965 , с. 39.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Мельников, 1992 , с. 209.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 Мельников, 1992 , с. 210.

- ↑ Коршунов, 1965 , с. 117.

- ↑ Коршунов, 1965 , с. 84.

- ↑ 1 2 Мельников, 1992 , с. 211.

- ↑ Мельников, 1992 , с. 211—212.

- ↑ 1 2 Мельников, 1992 , с. 212.

- ↑ 1 2 Мельников, 1992 , с. 213.

- ↑ Асветнікі, 2001 , с. 450—451.

- ↑ Козел, 2004 , с. 213.

- ↑ Мельников, 1992 , с. 158.

- ↑ Хрысціянства і беларуская культура: Матэрыялы III Міжнар. кангрэса беларусістаў «Беларуская культура ў дыялогу цывілізацый» / Рэдкал.: Л. Уладыкоўская-Канаплянік (гал. рэд.) і інш. — Минск: «Беларускі кнігазбор», 2001. — С. 97. — 208 с.

- ↑ Афанасій Філіповіч // Старажытная беларуская літаратура (XII—XVII стст.) / Уклад., прадм., камент. І. Саверчанкі. — 2007. — 466, 608 с.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Мельников, 1992 , с. 214.

- ↑ 1 2 «Диариуш» в оригинале (недоступная ссылка) . Дата обращения 20 ноября 2013. Архивировано 14 мая 2013 года.

- ↑ 1 2 Петров, Жук, 1997 , с. 165.

- ↑ Мельников, 1992 , с. 214—215.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Мельников, 1992 , с. 215.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Козел, 2004 , с. 159.

- ↑ Петров, Жук, 1997 , с. 163—164.

- ↑ 1 2 Асветнікі, 2001 , с. 451.

- ↑ 1 2 Мороз И. Г. Афанасий // Православная энциклопедия . — М. : Церковно-научный центр «Православная энциклопедия» , 2001. — Т. III. — С. 704—706. - 752 s. - 40,000 copies. — ISBN 5-89572-008-0 .

- ↑ 1 2 Мельников, 1992 , с. 216.

- ↑ 1 2 Кулагин А. Н. Афанасьевская часовня // Свод памятников истории и культуры Белоруссии. Брестская область. - Mn. : БелСЭ, 1990. — С. 131. — 424 с. - 25,000 copies. — ISBN 5-85700-017-3 .

- ↑ Кулагін, 2001 , с. 311.

- ↑ 1 2 Кулагін, 2007 , с. 18.

- ↑ Дзяржаўны спіс гісторыка-культурных каштоўнасцей Рэспублікі Беларусь / Склад.: В. Я. Абламскі, І. М. Чарняўскі, Ю. А. Барысюк. - Mn. : БЕЛТА, 2009. — С. 13. — 684 с. — ISBN 978-985-6828-35-8 .

- ↑ Мельников, 1992 , с. 215-216.

- ↑ Асіноўскі С. Такія розныя аднолькавыя лёсы // Беларуская мінуўшчына. — 1997. — № 3 . — С. 31—37 .

- ↑ Patron diecezji — święty męczennik Atanazy Brzeski (польск.) . Официальный сайт Люблинской епархии. Date of treatment December 26, 2013.

- ↑ Свято-Симеоновский кафедральный собор в Бресте . Официальный сайт Бреста. Date of treatment December 26, 2013.

Literature

Литература на русском языке

- Афанасий (Филиппович) // Русский биографический словарь : в 25 томах. - SPb. - M. , 1896-1918.

- Козел А. А. Философская мысль Беларуси. - Mn. : Амалфея, 2004. — 352 с. — ISBN 985-441-332-2 .

- Коршунов А. Ф. Афанасий Филиппович: жизнь и творчество. - Mn. : Наука и техника, 1965. — 183 с.

- Мельников А. А. Путь непечален. - Mn. : Издание Белорусской Православной Церкви Московского Патриархата, 1992. — 241 с.

- Мороз И. Г. Афанасий // Православная энциклопедия . - M .: Church Scientific Center "Orthodox Encyclopedia" , 2001. - T. III. — С. 704—706. - 752 s. - 40,000 copies. - ISBN 5-89572-008-0 .

- Таисия, монахиня (Карцева Т. Г.). Преподобномученник Афанасий Брестский // Русские святые. 1000 лет русской святости. — СПб: Азбука-классика, 2001. — С. 489—493.

- Юзефович Л. А. Самые знаменитые самозванцы: Ист. очерки. . — Москва: Олимп, 1999. — ISBN 5-7390-0492-4 .

Литература на белорусском языке

- Асветнікі зямлі Беларускай, X — пачатак XX ст. / Рэдкал.: Г. П. Пашкоў (гал. рэд.) і інш. - Mn. : БелЭн, 2001. — 496 с. — ISBN 985-11-0205-9 .

- Афанасій Берасцейскі // Вялікае княства Літоўскае / Рэдкал.: Г. П. Пашкоў (гал. рэд.) і інш. - Mn. : БелЭн, 2007. — Т. 1. — С. 267. — 688 с. — ISBN 978-985-11-0393-1 .

- Белазаровіч В. А. Гістарыяграфія гісторыі Беларусі. — Гродно: ГрДУ, 2006. — 345 с.

- Кулагін А. М. Праваслаўныя храмы Беларусі: энцыклапедычны даведнік. - Mn. : БелЭн, 2007. — ISBN 978-985-11-0389-4 .

- Кулагін А. М. Праваслаўныя храмы на Беларусі: энцыклапедычны даведнік. - Mn. : БелЭн, 2001. — 328 с. — ISBN 985-11-0190-7 .

- Прашковіч М. Слова пра Афанасія Філіповіча // Полымя. — 1965. — № 12 . — С. 174—177 .

- Пятроў М., Жук М. «…То не чалавек стаяў, стаяла вера» // Беларуская думка. - Mn. , 1997. — № 3 . — С. 159—165 .

- Цітавец А. А. Афанасій Брэсцкі // Рэлігія і царква на Беларусі: Энцыкл. давед. / рэдкал.: Г. П. Пашкоў і інш. - Mn. : БелЭн, 2001. — С. 26. — 368 с. — ISBN 985-11-0220-2 .

Литература на польском языке

- Mironowicz A. Diecezja białoruska w XVII i XVIII wieku. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku. — 2008. — 38, 100—103 с. — ISBN 978-83-7431-150-2 .

Links

- Преподобномученик Афанасий, игумен Брестский на сайте Православие.Ru