Transcranial magnetic stimulation ( TMS ) is a method that non-invasively stimulates the cerebral cortex using short magnetic pulses . Like transcranial electrical stimulation (TES) , TMS is sometimes associated with pain [1] and therefore should be used with caution.

The study of inhibitory processes of the brain using TMS is possible due to the ability of TMS to stimulate inhibitory cortical neurons. There are several methods for recording inhibitory responses using TMS. The first methodologically simplest way is to measure the duration of suppression of spontaneous muscle activity after the presentation of a magnetic stimulus (excitation by electromagnetic induction ). This method is called the Cortical Silent Period and allows the assessment of long-latent cortical inhibition (GABA-B). This type of inhibitory function is most sensitive to impaired activity of the basal ganglia (for example, with extrapyramidal disorders, dystonia, Parkinson's disease and other lesions of the basal structures) and therefore, its change can serve as an auxiliary indicator in the diagnosis of diseases of the basal ganglia. The disadvantage of this method is that the duration of suppression of muscle activity in response to TMS depends not only on the severity of the inhibitory activity of the cortex, but also on the intensity of TMS. With an increase in the intensity of electromagnetic irritation, the cortical quiet period lengthens and can be interrupted by a short burst of muscle activity (that is, divided into two components). This makes it difficult to assess the individual level of GABA-B inhibition and the diagnosis of its disorders.

Another approach to studying the excitability of the cerebral cortex is the method of paired magnetic stimulation (Paired-pulse TMS). It is based on measuring the amplitude of the motor evoked potential upon presentation of two magnetic stimuli of different intensities and at different interstimulus intervals (ISI). The intensity of the first stimulus is set below the motor threshold, that is, the first stimulus alone does not cause any motor responses. The intensity of the second stimulus is chosen so that it causes a motor potential with an amplitude of 0.8-1 millivolts during a single stimulation. With paired stimulation at interstimulus intervals from 1 to 6 milliseconds, the amplitude of the motor evoked potential decreases and the degree of this decrease reflects the level of short-latent inhibition (GABA-A).

Content

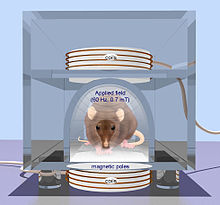

Principle of Operation

When the motor zone of the cerebral cortex is stimulated , TMS causes contraction of the corresponding peripheral muscles according to their topographic representation in the cortex. For example, when using a focal eight-shaped electromagnetic coil, the most optimal place for stimulation to receive motor responses from the distal muscles of the lower extremities is vertex, and to stimulate the motor zone of the hand, it is necessary to move the coil from the vertex laterally by 5-7 cm. Motor responses caused by TMS ( motor evoked potentials (IMP), Motor Evoked potentials (MEPs) ) can be registered using the method electromyography by means of electrodes attached to the skin in the area of the muscle (or muscles), which pr Nima involved in motor response to TMS. MVP registration is used to measure central conduction time (CMCT) and to study cortico-spinal excitability.

It is important to note that TMS excites the central motor conduction paths ( pyramidal tract ) not in a direct way, as TPP does, but through activation of interneurons with subsequent synaptic transmission of excitation to pyramidal neurons. Therefore, any violations of synaptic function lead to a decrease in amplitude and an increase in latency of the MEP. On the other hand, the high sensitivity of the MEP to changes in synaptic activity allows us to evaluate the excitability of the motor system of the brain (cortical excitability), including its excitatory (excitatory) and inhibitory (inhibitory) components.

History

The use of an alternating magnetic field to stimulate neural structures is based on the concept of Michael Faraday on electromagnetic induction (1831). In 1896, Jacques Arsene d'Arsonval first applied a magnetic field to humans and was able to induce phosphenes , the visual sensations that a person experiences without exposure to light on his eyes [2] .

The possibility of using magnetic stimulation (stimulation through electromagnetic induction) in psychiatry was discovered, like many other types of treatment, almost by accident. In 1902, A. Pollacsek and B. Beer, two of Freud's peers, patented a method for treating “depression and neurosis” in Vienna using an electromagnetic device. They probably believed that the electromagnet was able to exert a beneficial effect by mechanical shift of the brain. The hypothesis that stimulation can induce current in nerve fibers has not been advanced. Beer, positioning the solenoid above the head, also induced the effect of phosphenesis.

A new period of magnetic stimulation research began in 1985, when A. Barker et al. (Great Britain) for the first time experimentally demonstrated the possibility of muscle contraction caused by non-invasive effects on the central nervous system of an alternating magnetic field [3] . The use of non-invasive stimulation of the motor zone of the cerebral cortex made it possible to use the TMS method in the diagnosis of demyelinating neurological diseases (for example, multiple sclerosis ) by testing the functional state of the pathways and the integrity of the connections between the motor zone and other parts of the nervous system related to the motor paths.

In 1987, R. Bickford and M. Guidi first described short-term mood improvement in several healthy volunteers after exposure to the motor zones of the cerebral cortex with single stimuli during TMS [4] . This marked the beginning of scientific research on the effect of depolarizing magnetic fields in patients with various neurological and mental illnesses. Soon, studies were conducted on the effect of TMS on patients in a state of deep depression .

In parallel, a team of scientists led by Professor A. Pascual-Leone investigated the possibility of using TMS to treat patients with Parkinson's disease . It was shown that under the influence of an alternating magnetic field in patients, an increase in WMO and a reaction rate was observed, i.e., akinesia decreased. Two patients with depression in Parkinson's disease also showed improvement in mood after stimulation. The results were published two years later, in 1994 [5] [6] . More recent meta-analysis of the 2019 trials for the treatment of concomitant depression in Parkinson's disease with magnetic stimulation shows that the effect of TMS is no different from placebo [7] .

After 1994, the interest of physicians and scientists in TMS increased and a series of studies using animals and clinical trials in humans followed. The first controlled study to treat depression was conducted by M. George and E. Wassermann in 1995 [8] . In 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration ( FDA ) temporarily authorized the use of Neuronetics magnetic stimulants to treat depression, and they did so based on a study published in the journal Biological Psychiatry [9] . Later in 2010, the FDA revoked permission for this type of treatment, since a denial article was published in 2010 in the same journal “Biological Psychiatry”, telling about the statistical insignificance of the results in a detailed examination of the 2007 study data, as well as about the high probability of violations during of the study, which some experimental data talked about. [10] .

An early systematic review of 2003 showed that there are insufficient data for reliable conclusions about the effectiveness of this treatment method for obsessive-compulsive disorder [11] . In 2018, the U.S. Federal Food and Drug Administration ( FDA ) approved TMS (transcranial magnetic stimulation) as a treatment for adult patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder in whom the pharmacological treatment of the latter exacerbation with antidepressants in adequate doses did not have the desired effect [12] . Similar permissions to use the methodology are usually given for a specific model of the device (for example, in this case for Brainsway by Brainway Ltd.).

A systematic review of the treatment of epilepsy with magnetic stimulation reveals poor quality studies and headaches in patients after the procedures [1] .

A systematic review of the treatment of magnetic stimulation of patients with spinal cord injury shows a low quality of the studies, and no reliable conclusions can be drawn from them [13]

Clinical application

Transcranial magnetic stimulation can be limitedly used in psychiatry , neurology , epileptology, for: experimental treatment: depression , Parkinson's disease , epilepsy , auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia , obsessive-compulsive disorders , amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, recovery from spinal cord injury, rehabilitation for the prevention of stroke in children with sickle cell anemia , relief of symptoms in motor neuron disease, for the correction of taste disorders. But the data of clinical studies are not yet enough for final conclusions about the effectiveness of TMS in these diseases [14] [15] .

Application of TMS in the Russian Federation

According to the order of the Ministry of Health of Russia dated December 29, 2012 No. 1705n “On the procedure for organizing medical rehabilitation”, transcranial magnetic stimulation devices are included in the “Standard for equipping the inpatient unit for medical rehabilitation of patients with impaired central nervous system function” [16] . TMS is also included in the Standard for Specialized Medical Care for Pituitary Neoplasms [17] , the Standard for Specialized Medical Care for Alzheimer's Disease [18], and the Standard for Primary Health Care for Children with Delayed Sexual Development [19] .

Side Effects and Safety

The knowledge obtained to date allows to inform the patient about possible minor unwanted effects and how to cope with them. The most common question before rTMS, as well as diagnostic TMS, is the likelihood of a seizure and headache. In exceptional cases, when this happens (or rather, when there is a likelihood of an attack), it is important to understand what happened, what stimulation parameters need to be changed during treatment to reduce the risks of undesirable effects, how to act in case of an attack.

Side Effects

Side effects can be divided into three main groups: systemic (somatic), psychiatric and neurological. Somatic and neurological side effects cause the patient the most questions and require special attention.

- Systemic side effects:

- gastrointestinal tract: nausea ;

- cardiovascular system: theoretical risk of provoking arrhythmias when the inductor is located and stimulation over the region of the heart;

- skeletal muscle: pain, muscle contraction, arthralgia ;

- skin: erythema .

- Psychiatric side effects:

- anxiety;

- acute dysphoria , tearfulness;

- attacks of unmotivated laughter (with the temporary disappearance of speech in response to stimulation of Brock's zone in studies of the center of speech);

- suicidal thoughts;

- induced mania.

- Neurological side effects.

- Pain in the muscles of the cranial vault and the innervation zone of the superficial nerves ( trigeminal nerve ), tics of the face (the result of activation of the branches of the facial nerve ). In these cases, it is recommended to stop the session, change the position of the inductor above the head (for example, turn it and move it centrally above the left hemisphere) and reduce the intensity of the stimulus used, taking into account the PMO.

- Headache, discomfort and local pain. In these cases, simple analgesics (in exceptional cases), a change in the location of the inductor above the head, and a decrease in intensity (% of PMO) can help.

- Fatigue and fatigue.

- Dizziness.

- Cognitive impairment. Short-term positive and negative effects can be observed. Most of them do not lead to any changes.

- Hearing loss. Cases of an increase in the auditory threshold are described (short-term hearing loss in humans and long-term in animals when using standard inducers). The patient and the doctor conducting the examination should use earmolds ( ear plugs ). Patients with hearing loss or tinnitus associated with TMS should be referred for an audiometric examination . For patients who have a history of tinnitus, hearing loss, and those undergoing simultaneous treatment with ototoxic drugs, the decision to conduct TMS should be made taking into account the ratio of the risk of possible complications and the expected benefit.

- Ophthalmic complications. A case of retinal detachment and vitreous stratification during TMS has been described [20] .

- Cytotoxicity.

- Inducing accidental seizures.

Contraindications

A definite contraindication for the diagnostic and therapeutic TMS is the presence in the patient of any metal medical devices and foreign bodies, especially in the head.

TMS is used in the examination of children taking into account age-related characteristics associated with the maturity of the corticospinal tract . At the beginning of attempts to use TMS in practice, it was believed that pregnancy was a direct contraindication to its implementation. In recent years, there have been reports of the possibility of using rTMS (and ECT) in the treatment of depression in pregnant women without any negative effects on the patient and consequences for the fetus [21] [22] [23] [24] . When examining pregnant women, the magnetic field does not reach the fetus. In addition, cases of successful magnetic stimulation in pregnant women are already known. Before the publication of the final results of controlled trials, it is recommended in each case to individually approach the use of TMS for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in pregnant women and children, and conduct examination and treatment in hospitals and specialized laboratories under the supervision of specialists.

- Contraindications associated with the direct action of the electromagnetic field:

- The presence of intracranial metal implants.

- The presence of an implanted pacemaker (theoretical risk, since the magnetic field usually does not reach the zone where the stimulator or wires and electrodes coming from it).

- The presence of implanted pumps, pumps (provided that they are located in close proximity to the magnetic field inductor).

- The presence of hearing aids and cochlear implants .

- The presence of implanted devices for deep brain stimulation (DBS), since electromagnetic induction affects the cables located in the brain, changing their functional effect on the target tissue.

- Contraindications related to the increased risk of inducing seizures:

- The patient has focal changes or encephalopathy (tumors, ischemia, bleeding, meningitis , encephalitis ) associated with the presence of an epileptogenic focus.

- Concomitant drug treatment with drugs that affect the excitability of the cerebral cortex (some antidepressants, nervous system stimulants and antipsychotic drugs).

- Head injury with loss of consciousness for more than 15 seconds in history.

- A history of neurosurgical interventions on the brain.

- History of epilepsy or epileptic seizures.

- Злоупотребление алкоголем или наркотиками с последующим резким прекращением их потребления.

- Случаи эпилепсии в семье пациента.

- Ситуации, при которых конвульсии могут стать причиной серьезных осложнений с потенциальными последствиями (например, сердечно-сосудистая декомпенсация или повышенное внутричерепное давление).

Устройство и работа магнитного стимулятора

Принцип действия стимулятора основан на разряде конденсатора высокого напряжения и большой силы тока на стимуляционную катушку из медного провода (т. н. «индуктор», или «койл») в момент замыкания высоковольтного ключа. В этот момент в индукторе возникает импульсное магнитное поле (до 4 Тесла [25] ), которое индуцирует в близко расположенных тканях тела пациента ток, вызывающий нервный импульс.

Максимально достижимая интенсивность магнитного поля зависит от частоты стимуляции и уменьшается с её увеличением. Эта зависимость обусловлена ограниченной способностью схемы заряда конденсатора зарядить конденсатор до требуемого напряжения в паузу между стимулами.

Протекание тока через катушку индуктора вызывает её нагрев. Чем выше мощность стимула и частота стимуляции, тем быстрее происходит нагрев рабочей поверхности индуктора, которая при непосредственном контакте с пациентом может вызвать гиперемию или ожог. Использование индукторов с принудительным охлаждением позволяет увеличить время непрерывной работы без перегрева.

Типы стимулов

- Монофазный стимул — стимул, при котором ток в катушке индуктора протекает в одном направлении, нарастая по синусоидальному закону и спадая по экспоненте.

- Бифазный стимул — стимул, при котором форма тока в катушке индуктора характеризуется одним периодом затухающей синусоиды.

- Бифазный burst стимул — бифазная стимуляция, в которой вместо одиночного импульса выдается серия бифазных стимулов с высокой частотой (до 100 Гц) и убывающей амплитудой.

- Парный монофазный стимул — два стимула с заданным межстимульным интервалом и амплитудой, задаваемой независимо для каждого стимула.

Выбор типа индукторов

При выборе того или иного индуктора учитываются генерируемая им пиковая мощность магнитного поля и, соответственно, пиковая мощность электрического поля, а также форма и размер катушки.

Особенности генерируемого магнитного поля в большей степени зависят от конструкции катушки индуктора. Наиболее распространенными индукторами являются кольцевой, двойной и двойной угловой.

В кольцевых индукторах область максимальной магнитной индукции расположена у внутреннего края катушки (ребра внутренней окружности). В двойных и двойных угловых индукторах максимум плотности магнитного поля приходится на центр индуктора (область, где соприкасаются оба «крыла»), что позволяет получать хорошо сфокусированное, но относительно слабое импульсное магнитное поле.

Глубина проникновения магнитного поля прямо пропорциональна диаметру используемой катушки и силе тока, протекающего через неё. Малые по размеру индукторы создают высокую индукцию магнитного поля у поверхности кожи и поэтому, как и двойные индукторы, хороши для воздействия на поверхностные структуры. Большие кольцевые катушки создают глубоко проникающие поля, но их воздействие слабо фокусировано.

See also

- Магнитобиология

- Магнитоэнцефалография

- Микрополяризация

- Электросудорожная терапия

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 Chen R, Spencer DC, Weston J, Nolan SJ. Транскраниальная магнитная стимуляция при лечении эпилепсии = Transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of epilepsy // Cochrane library. — John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2016. — 11 августа. — DOI : 10.1002/14651858.CD011025.pub2 . Архивировано 18 апреля 2019 года.

- ↑ Wassermann EM et al. Safety and side-effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation //Handbook of transcranial magnetic stimulation. London: Arnold. – 2002. – С. 39-49.

- ↑ Barker AT, Jalinous R., Freeston IL Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex (англ.) // The Lancet : журнал. — 1985. — Vol. 325 , no. 8437 . — P. 1106—1107 .

- ↑ Bickford RG et al. Magnetic stimulation of human peripheral nerve and brain: response enhancement by combined magnetoelectrical technique. (англ.) // Neurosurgery : журнал. — 1987. — Vol. 20 , no. 1 . — P. 110—116 .

- ↑ Pascual-Leone A. et al. Akinesia in Parkinson's disease. I. Shortening of simple reaction time with focal, single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (англ.) // Neurology : журнал. - 1994. - Vol. 44 , no. 5 . — P. 884—884 .

- ↑ Pascual-Leone A. et al. Akinesia in Parkinson's disease. II. Effects of subthreshold repetitive transcranial motor cortex stimulation (англ.) // Neurology : журнал. - 1994. - Vol. 44 , no. 5 . — P. 892—892 .

- ↑ Liang Zhou, Zhiwei Guo, Guoqiang Xing, Haitao Peng, Mengjie Cai, Huaping Chen, Morgan A. McClure, Lin He, Liangwen Xiong, Bin He, Fei Du, Qiwen Mu. Antidepressant Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Over Prefrontal Cortex of Parkinson's Disease Patients With Depression: A Meta-Analysis // Frontiers in Psychiatric Parkinson’s Disease Patients With Depression: A Meta-Analysis // Frontiers in Psychiatry Best Practices in Psychiatry): Journal. - Frontiers media SA [CH], 2019. - 29 January. - ISSN 1664-0640 . - DOI : 10.3389 / fpsyt.2018.00769 . - PMID 30761029 . Archived on April 19, 2019.

- ↑ George MS et al. Daily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves mood in depression. (English) // Neuroreport: magazine. - 1995. - Vol. 6 , no. 14 . - P. 1853-1856 .

- ↑ John P. O'Reardon, H. Brent Solvasonb, Philip G. Janicakc, Shirlene Sampsond, Keith E. Isenberge, Ziad Nahasj, William M. McDonaldf, David Averyg, Paul B. Fitzgeraldh, Colleen Looi, Mark A. Demitrackk, Mark S. Georgej, Harold A. Sackeiml. Efficacy and Safety of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in the Treatment of Exacerbations of Deep Depression: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (English) = Efficacy and Safety of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in the Acute Treatment of Major Depression: A Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial // Biological psychiatry: Journal. - Elsevier, 2007 .-- 16 June ( vol. 62 , iss. 11 ). - P. 1208-1216 . - ISSN 0006-3223 . - DOI : 10.1016 / j.biopsych.2007.01.01.018 .

- ↑ Eunice Yua, Peter Lurie. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Not Proven Effective // Transological Magnetic Stimulation Not Proven // Biological psychiatry: Journal. - Elsevier, 2009 .-- October 5 ( vol. 67 , iss. 2 ). - P. 13 . - ISSN 0006-3223 . - DOI : 10.1016 / j.biopsych.2009.03.03.026 . The article is a rebuttal providing indirect evidence of 2007 manipulation and manipulation of experimental data

- ↑ José Luis Rodriguez ‐ Martin, José Manuel Barbanoj, V Pérez M Sacristan. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of obsessive ‐ compulsive disorder // Cohrane library. - John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003 .-- April 22. - DOI : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD003387 .

- ↑ FDA permits marketing of transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder (FDA permits the commercial use of transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder ) . https://www.fda.gov . US Food and Drug Administration (August 20, 2018). Date of treatment April 18, 2019. Archived November 1, 2018.

- ↑ Boldt I, Eriks-Hoogland I, Brinkhof MWG, de Bie R, Joggi D, von Elm E. Other treatments other than medication in people with chronic pain after spinal cord injury = Treatments other than medication for people with chronic pain after spinal cord injury // Cohrane library. - John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014 .-- November 28. - DOI : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD009177.pub2 . Archived on May 11, 2018.

- ↑ search result "transcranial" in Cochrane's medical evidence library . https://www.cochrane.org . John Wiley & Sons, Inc .. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- ↑ search result for "TMS" (Transcranial magnetic stimulation) in the Cochrane Medical Evidence Library . https://www.cochrane.org . John Wiley & Sons, Inc .. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- ↑ Order of the Ministry of Health of Russia dated December 29, 2012 No. 1705n. Archived September 24, 2015 on Wayback Machine , Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation

- ↑ Standard of specialized medical care for pituitary neoplasms. , Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation

- ↑ Standard for specialized care for Alzheimer's disease. , Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation

- ↑ Standard of primary health care for children with delayed sexual development. , Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation

- ↑ Becker R.A., Bykov Yu.V. Depression in ophthalmology - the cause and effect of eye diseases // Mental disorders in general medicine. - 2016. - No. 3. - S. 36–42.

- ↑ Klirova M. et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in major depressive episode during pregnancy. (English) // Neuro endocrinology letters: journal. - 2008. - Vol. 29 , no. 1 . - P. 69-70 .

- ↑ Kim DR et al. A survey of patient acceptability of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) during pregnancy // Journal of affective disorders: Journal. - 2011. - Vol. 129 , no. 1 . - P. 385-390 .

- ↑ Kim DR et al. An open label pilot study of transcranial magnetic stimulation for pregnant women with major depressive disorder // Journal of Women's Health: Journal. - 2011. - Vol. 20 , no. 2 . - P. 255-261 .

- ↑ Gahr M. et al. Successful treatment of major depression with electroconvulsive therapy in a pregnant patient with previous non-response to prefrontal rTMS. (English) // Pharmacopsychiatry: Journal. - 2012. - Vol. 45 , no. 2 . - P. 79-80 .

- ↑ Description of the magnetic stimulator "Neuro-MS / D". neurosoft.com

Literature

- Nikitin S.S., Kurenkov A.L. Magnetic stimulation in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases of the nervous system. A guide for doctors. M .: SASHKO, 2003 .-- 378 p.

- M.A. Rose, M.O. Rosa Therapeutic rhythmic transcranial magnetic stimulation. Ivanovo: scientific publication, 2012. - 48 p.

- George MS, Nahas Z., Bohning DE TMS and neuroimaging. In: George MS, Belmaker RH (eds.). Transcranial magnetic stimulation in neuropsychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2000.