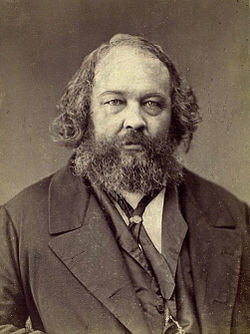

Mikhail Aleksendrovich Bakunin ( May 18 [30], 1814 , the village of Pryamukhino , Novotorzh Uyezd , Tver Province , Russian Empire - June 19 [ July 1 ] 1876 , Bern , Switzerland ) - a Russian thinker and revolutionary from the Bakunin clan, one of the theorists of anarchism , populism . It stands at the origins of social anarchism .

| Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Date of Birth | May 30, 1814 |

| Place of Birth | |

| Date of death | July 1, 1876 (62 years old) |

| Place of death | Bern , Switzerland |

| A country | |

| Alma mater | |

| Direction | and |

| Period | 1840 - 1876 |

| Core interests | |

| Significant ideas | anarchist , pan-Slavist , one of the ideologists of populism |

| Influenced | , , , , , , , and |

| Signature | |

Biography

The early years

Born in the Tver family estate of Pryamukhino in the family of the provincial leader of the nobility Alexander Mikhailovich Bakunin and Varvara Alexandrovna , nee Muravyova (1792-1864). His mother was a second cousin to the Decembrists Muravyov : Nikita , Artamon , Sergey and Matvey . She was 24 years younger than her husband. In her youth she was known as a "fashionista" and "socialite". Having married, she lived in perfect harmony with her husband and was known as a strict, almost tyrannical mother. She herself, like her husband, was engaged in the upbringing and education of children - she taught them literature and music. In total, the family of Alexander Mikhailovich and Varvara Aleksandrovna Bakuninins had 11 children.

Fifteen years old, in 1829, became a cunker of the Petersburg Artillery School . Three years later, in January 1833, he was promoted to ensign and left in the officer classes. However, in June 1834, Bakunin was expelled from the first officer’s course for impudence committed against the head of the school, General I. O. Sukhozanet [Note. 1] . He was sent to serve in the army in one of the batteries located in Molodechno, Minsk province. In the autumn of 1834, the brigade in which Bakunin served was transferred to the Grodno province.

Stankevich Circle

A year later, in 1835, speaking ill, he resigned and settled, contrary to his father’s wishes, in Moscow , where, having entered into a friendly relationship with Stankevich’s circle, he devoted himself to the study of German philosophy. During this period, Mikhail Alexandrovich decides to devote himself to scientific activity.

Since the beginning of 1836, Bakunin has been living in Moscow, periodically visiting his parents' estate and Petersburg. He meets and often draws close with many well-known representatives of the Russian intelligentsia. He is one of the main preachers of Stankevich’s philosophical circle, and is a member of the literary salon of his relative, E. G. Levashova , in which Pushkin and Chaadaev visited. He maintains close, although not cloudless, relations with Belinsky , Botkin , Katkov , and Granovsky . In 1839-1840 he met Herzen , Ogaryov .

With all his passion, MA Bakunin devoted himself to the study of German classical philosophy, reads in the scripts Kant , Fichte and, finally, Hegel . Then, in the circles of the Russian intelligentsia, there was a lot of controversy surrounding the famous position of this philosopher "everything real is rational, everything rational is real." Bakunin interprets this formula in a conservative manner. “Reconciliation with reality in all respects and in all spheres of life,” he wrote in 1838 on the pages of the magazine “Moscow Observer” edited by Belinsky , “is a great task of our time.”

Departure abroad

From July 16 to November 14, 1839, Mikhail Bakunin lived in St. Petersburg. During these months, he often visited the house of Avdotya Panayeva , where V.G. Belinsky, N.V. Kukolnik, I.P. Sakharov, Bryullov and other famous figures of Russian culture of that time gathered. Bakunin, as usual, introduced this circle to the contemporary works of German philosophers. During this period, Mikhail Bakunin intensively sought money for his trip abroad, where he wanted to continue his philosophical education. On March 22, 1840, he wrote a long and very eloquent letter to his parents asking them to allow a trip to Berlin and asking for money for it. His father gave his consent to this trip, but did not give money for the trip. Bakunin in desperation turned to Herzen for help. Herzen replied that he was lending Bakunin 2,000 rubles indefinitely. A few days before departure, there was a quarrel with Katkov at Belinsky’s apartment. Bakunin hit Katkov with a stick on the back, and he hit him in the face. Bakunin called Katkov to a duel , but the next day he thought better of it and sent him a note asking him to transfer the place of the match to Berlin, since, according to Russian law, the survivor entered the soldiers. In fact, the case was essentially hushed up, but all the common friends: I.I. Panaev, V.G. Belinsky, N.P. Ogarev, V.P. Botkin, and Yazykov - were in this incident on the side of Katkov. Only Herzen was neutral.

From 1840, Mikhail Bakunin began to live abroad, where he went (initially to Berlin ) to study German philosophy, where he listened to the lectures of the students of Hegel and Schelling , who then opposed Hegel's philosophy in defense of Christian revelation. Having thoroughly studied Hegel, especially his “Logic”, Bakunin soon switched to the side of the so-called “left” Hegelians , who at that time published the “German Yearbook of Sciences and Arts” (“Deutsche Jahrbücher”, previously called “Hallesche Jahrbücher”), in which Bakunin in 1842 posted a revolutionary article that made a lot of noise in Germany: “Reaction in Germany” (Die Reaction in Deutschland, under the pseudonym Jules Elizard - Jules Elizard) . 2] . In Berlin, he draws closer to Ivan Turgenev . At the same time, Bakunin published a booklet in Leipzig criticizing Schelling's philosophy ("Schelling und die Offenbarung. Kritik des neuesten Reactionsversuchs gegen die Philosophie"), which was highly praised by the left Hegelians. At the beginning of his stay in Berlin, in addition to letters to friends (especially to Herzen ), Mikhail Bakunin wrote articles for "Domestic Notes". Here, in 1840, his article on contemporary German philosophy and correspondence from Berlin (in “Mixtures”) was published.

In 1842, Mikhail Bakunin formed a strong desire to stay in Europe forever and not return to Russia. So, in his letter to brother Nikolai on October 9, he wrote:

“After a long reflection and for reasons that Turgenev will explain to you, I decided never to return to Russia. Do not think it was a frivolous decision. It is connected with the inner meaning of my whole past and present life. This is my fate, the lot, which I can not resist, should not and do not want.

Do not also think that it would be easy for me to decide on this — to forever abandon the fatherland, from you, from everything that I have still loved. I have never felt so deeply with what threads I am connected with Russia and with all of you, as now, and I have never so vividly imagined a lonely, sad and difficult future, probably awaiting me ahead in a foreign land, and, despite this, I will irrevocably made up my mind.

I am not fit for the present Russia, I am spoiled for it, but here I feel that I want to live more, I can act here, I still have a lot of youth and energy for Europe. ”

In the spring of 1842, Bakunin met with Dresden who had arrived in Dresden and, by that time, had become extremely popular German revolutionary-democratic poet Herweg . They became friends and even began to rent one apartment for two. At the beginning of 1843, a decree was followed to expel Herweg from Prussia for his revolutionary poems. Bakunin was also taken under surveillance by the Prussian police. Herweg decided to leave Germany altogether and went to Switzerland. Bakunin left with him.

The beginning of revolutionary activity

In Switzerland, Bakunin settled in Zurich , where he began to communicate in a circle of radically minded intelligentsia. He established friendships with the family of the professor of medicine, Philipp Friedrich Vocht . This was a free-thinking and even radically-minded family, in which there were four adult sons, with the eldest of them Karl , a naturalist professor, and later A.I. Herzen was closely connected. Bakunin, of the sons of Foht, was closest (throughout his life) to Adolf. In 1843, Bakunin established relations with German and Swiss communist revolutionaries (in particular, his acquaintance of that period, Wilhelm Weitling , a radical revolutionary communist, had a strong influence on Bakunin's worldview), which the Russian government soon became aware of. To the government’s demand to return to Russia, he refused.

In 1844, the governing Senate sentenced “former lieutenant” Mikhail Bakunin, who refused to return to Russia, to deprive him of “noble dignity and all the rights of his fortune”, as well as “in case of appearance in Russia, to send to hard labor in Siberia”. All property belonging to him in Russia was confiscated to the treasury [Note. 3] .

From 1844 to 1847 he lived mainly in Paris and here he became close friends with Proudhon and took part in the newspaper La Reforme. In the spring and summer of 1844 , while living in Brussels, Bakunin met with Joachim Lelewel , a historian and public figure, leader of the revolutionary wing of the Polish emigration, who had previously participated in arms in the Polish uprising . Lelevel made a great impression on Bakunin. After that, Bakunin became actively interested in the Polish question and began to formulate his own program of struggle for the liberation of Russia and the Slavs. Bakunin’s personal acquaintance with Marx and his ideas belongs to the same period of life in Paris.

On November 29, 1847, Mikhail Bakunin in Paris, at a banquet held in honor of the participants of the Polish uprising (1830-1831), made a speech directed “primarily against Russian autocracy” [2] . The Russian government becomes aware of this, and soon at the request of the Russian ambassador in Paris, Bakunin was expelled from Paris. He spent several months in Brussels, but as soon as the February Revolution broke out in France, he immediately returned to Paris and here with energy and passion set about organizing the Paris workers. His energy seemed dangerous even to members of the interim government, and they hastened to remove him from Paris, giving him an assignment to Germany and the Slavic lands.

In Prague, he wrote an article entitled “Foundations of a New Slavic Policy”, published in Polish in the newspaper Dziennik Domowy and German in Slavische Jahrbücher for 1848 (No. 49). This article introduces the idea of the All-Slavic Federation, and expresses the idea of the right of each of its citizens to a piece of land.

Prague Uprising

In June 1848, Bakunin took an active part in the Prague popular uprising ("Svyatoduhovsky" uprising, crushed by troops), to which he fell, having originally arrived in Prague at the Prague Slavic Congress [Note. 4] .

After the suppression of the uprising in Prague, Bakunin fled to Germany, where he continued to maintain his Slavic ties and published in German, “Appeal to the Slavs” (“Aufruf an die Slaven”), directed against the German aspirations of the Frankfurt parliament. In this appeal, he sets the goal of the European revolutionary movement "the establishment of a universal federation of European republics"

In May 1849, Bakunin became one of the leaders of the uprising in Dresden . After the suppression of the uprising, Bakunin fled to Chemnitz , where he was arrested. He was sentenced to death by a Saxon court. He refused to sign the king’s request for clemency, but the death penalty was still replaced by his life sentence. Soon, however, the Saxon government extradited him to Austria, where he was tried again in 1851 by an Austrian court and sentenced to death for participating in the Prague uprising, and this time replaced by life imprisonment.

Expulsion to Petersburg

In the same 1851, it was issued by the Austrian government to the tsarist government of Russia . He was serving a sentence in the Alekseevsky ravelin of the Peter and Paul Fortress (from 1851 to 1854) and in the Shlisselburg Fortress (from 1854 to 1857).

While imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress, Bakunin wrote at the request of the Russian Emperor Nicholas I his famous work “Confession,” in which he outlined his view of the revolutionary movement and the Slavic issue.

Link to Siberia

In 1857, after 7 years of imprisonment, yielding to the insistent chores of the Bakunin family and after certifying the doctors that the obesity of the heart that started at Bakunin could lead to an imminent death, Alexander II allowed him to be transferred to eternal settlement in Siberia .

Mikhail Bakunin settled in exile in Western Siberia , in Tomsk . Initially, he lived and rested in the family of the tradesman Bardakov, whose small wooden house was located on Magistratskaya Street , near Samokhvalov’s house, where later the house of the merchant I. I. Smirnov [3] stood.

In Tomsk, he married (Bakunin was married by his relative Muravyov-Amursky ) to the daughter of the neighboring Polish nobleman Ksawery Kwiatkowski ( Polish. Ksawery Kwiatkowski ) - 18-year-old Antonina Kwiatkowska ( Polish. Antonina Kwiatkowska ) [Note. 5] . The house in which M.A. Bakunin lived was subsequently rebuilt in stone (modern address is No. 14 on Bakunin Street ).

Later, at the request of Muravyov-Amursky, he was transferred to Irkutsk [Note. 6] .

In the fall of 1861, Mikhail Bakunin escaped from Siberia via Japan and the United States to London , where Herzen was accepted as a publisher of The Bell .

In exile

In England, he began his political activity with an appeal to “Russian, Polish and all Slavic friends”, in which he called for the destruction of existing, historically formed and held only by violence states, especially such as Austria and Turkey, and partly the Russian Empire. He expressed a desire for peaceful federalist organizations, going from the bottom up, based on the free will of mutually agreeing Slavic tribes and peoples. At the same time, he invited all Slavic peoples to accept the slogan of the then Russian revolutionaries: “land and freedom” and expressed the hope that the revived “cotton Poland” would abandon its historical claims and give Little Russians, Belarusians, Lithuania and Latvians the right of free self-determination.

At the end of 1862, he published the pamphlet “People's Business. Romanov, Pugachev or Pestel? ”, In which he wrote that Alexander II does not understand his mission and ruins the cause of the entire dynasty. Bakunin argued that if the tsar sincerely decided to become a “zemstvo tsar”, convened a zemstvo council and adopted the “land and will” program, then advanced Russian people and the Russian people would be most willing to follow him, preferring him to Pugachev and Pestel . In this pamphlet, for the first time, certain populist tasks of the Russian progressive youth are posed and then the same program of Slavic federalism is repeated, which was described in its previous articles.

In 1862-1863 he took part in the Polish uprising . February 24, 1863 he arrived in Stockholm to prepare the Polish landing in the Palanga region (under the command of Lapinsky), which ended in failure.

From 1864 to 1868 he lived in Italy (until 1865 in Florence , then in Naples ), where he organized a number of socialist organizations directed simultaneously against all existing historically developed states and against Christian republicanism Mazzini .

In 1865-1866 he wrote his program document - “Revolutionary Catechism”, which should not be confused with the “ Catechism of a Revolutionary ”, written later (in 1869) by Nechaev [4] [5] .

In 1867, he participated in the Congress of the Democratic League of Peace and Freedom in Geneva and delivered a speech in which he proved the impossibility of a peaceful confederation of existing states based on violence and centralization of government, and demanded their destruction and replacement by free autonomous societies organized from the bottom up ".

In September 1864, at a conference in London, Karl Marx established the International Workers' Partnership - I International . In 1868, Bakunin joined the international union of workers founded by Marx and tried to join the League of Peace and Freedom, but this turned out to be impossible, since most of the members in it were not even socialists. On the other hand, the leaders of the International did not fully share Bakunin's anarchist views. Bakunin, having entered into a partnership with M. A. Karaev, opposed the “statesman” Marx and began the struggle for supremacy in this organization, which ultimately led to a split in this organization .

Having left the League of Peace and Freedom in 1868, Bakunin formed a new organization - the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy (Alliance internationale de la Democratie socialiste). As part of this union, a special secret international brotherhood was established, the central committee of which vested Bakunin with dictatorial powers. In the same 1868, Bakunin, together with the Russian emigrant N. I. Zhukovsky, founded in Zurich the journal Narodnoe Delo, the first issue of which preached the anti-state program and recognized mental liberation of the person as possible only on the basis of atheism and materialism, and socio-economic liberation as requiring the abolition of all inheritance property, the transfer of land to communities of farmers, and factories, capital and other implements of production - to labor associations, the equalization of rights of women with men, the abolition of marriage and family and public education of children.

In 1869, the publication of the “ Manifesto of the Communist Party ” by Karl Marx, translated by Mikhail Bakunin, was published in Russian.

In 1869 , when major student unrest began in Russia, Bakunin took an active part in campaigning among young people and became close to Nechayev who had come abroad, who “attracted him with his extraordinary energy” . Nechaev was a supporter of the principle “the end justifies the means” and recognized the deception and complete enslavement of revolutionary figures as a necessary tool of the revolution, essentially fundamentally sharply different from Bakunin, but Bakunin obeyed him in many ways, which, of course, greatly compromised himself in the eyes of many .

In 1871, Bakunin took part in an attempt to organize the Lyon revolutionary commune, and again he had to sacrifice his main views towards revolutionary Jacobinism. In 1872 , at the Hague Congress of the International, a detailed report was made by N. Utin , accusing Bakunin of organizing organizations that disagree with the basic principles of the union, and of participating in the immoral revolutionary enterprises of Nechaev. Bakunin was expelled from the International by a small majority. This caused major disagreement, leading in the same year to the collapse of the union. On the side of Bakunin were all the southern sections of the International and most of the revolutionary workers' organizations in the Roman countries of Europe.

In the years 1872-1876, Bakunin lived in Lugano and Locarno . Bakunin lived in great need, although one of his Italian followers, Kafiero, bought a small villa for him, and his brothers allotted to him by this time a part of the hereditary property. At this time, Bakunin was mainly engaged in organizing various revolutionary attempts in Italy and setting forth his views in a number of works, of which not one was completely finished.

After breaking up with Nechaev, Bakunin did not take a personal part in the Russian revolutionary movement, but his ideas were widely spread among Russian revolutionaries in the early 1870s, and in the sphere of revolutionary populism the Bakuninists were one of the largest groups.

Death

Mikhail Aleksandrovich Bakunin died on June 19 ( July 1 ), 1876 in Bern , Switzerland , in a hospital for laborers, where he was placed at his insistence. He arrived in Bern from Lugano a few weeks before his death and directly told his friends Vogt, to whom he appeared that he had come to die. “I came here, either so that the doctors would lift me to my feet, or so that they would close my eyes forever,” he told his friends. A week before his death, Mikhail Bakunin stopped eating and drinking. In response to the offer to drink a cup of broth, he said: “Think about what you are doing with me, forcing me to drink it; I know what I want. " But he didn’t refuse buckwheat porridge : “Porridge is another matter”. These were his last words.

Mikhail Aleksandrovich Bakunin was buried at the Bremgarten cemetery in Bern (plot 9201 , grave 68 ), and a tombstone was placed over his grave Vogt. At his funeral was attended by more than two hundred people: Germans, Poles, Swiss. There were no Russians.

Bakunin's personality

N.E. Wrangel , who in the 1860s witnessed Bakunin’s performance at the Karuzh beer house near Geneva, described his impressions of him:

He stayed as befits European fame: self-confidently, authoritatively and graciously simple. <...> His oratory temperament was astounding. This man was born to be a tribune of the people, and it was difficult to remain indifferent when he spoke, although the content of his speech did not contain anything of value. There were more exclamations in her than thoughts, loud, pompous phrases and words, loud promises, but her voice and enthusiasm were indescribable. This man was created for the revolution, it was his natural element, and I am convinced that if he could manage to rebuild any state in his own way, introduce a form of government there, he would be there the next day, if not earlier, he would rebel against his own brainchild and become the head of his political opponents and engage in battle in order to overthrow himself. With his enthusiasm, he infected everyone, and we all together brought him out of the hall in our arms.

- Memories: from serfdom to the Bolsheviks.

Philosophy

Bakunin rejected static and hierarchical power systems in any form. He also did not recognize any form of hierarchical power emanating from the will of the sovereign or even from a state with universal suffrage. In his book "God and the State [6] ", he wrote:

Man's freedom consists solely in the fact that he obeys natural laws, because he himself recognizes them as such, and not because they were externally imposed on him by any extraneous will - divine or human, collective or individual.

Bakunin rejected the idea of any privileged position or class, since social and economic inequality resulting from the class system (as well as the system of national and gender oppression) is incompatible with the principles of individual freedom. While the followers of the ideas of liberalism insisted that free markets and constitutional governments imply individual freedom, Bakunin argued that capitalism and the state in any form are incompatible with the individual freedom of the working class and peasantry.

Freemasonry

Bakunin was in the Masonic lodges of the Great East of Italy . According to some reports, he was consecrated into Freemasonry at the initiative of J. Garibaldi on the island of Caprera in the early 1860s (according to other sources in 1845). In 1864, he was affiliated with the Il Progresso sociale (Social Progress) box in Florence. Received on April 3, 1865, a 32 ° Patent for the Children’s School of Law from the Consistory 32 ° of the Supreme Council of the Children’s School of Law . Also a member of the Masonic lodge in Florence.

In 1864-1865 he created the secret society "International Brotherhood". In 1867-1868 he spoke with the propaganda of his ideas at the congresses of the League of Peace and Freedom in Geneva, the vice-president of this congress. He intended to use Masonic organizations for the needs of the revolutionary struggle. In 1868, he created in Switzerland the paramason semi-anarchic organization International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, which was admitted to the First International as one of the Geneva sections [7] [8] [9] .

Proceedings

The most significant of Bakunin’s works was published in 1874 as a separate book, entitled Statehood and Anarchy . The struggle of two parties in the international society of workers. In this book, Bakunin argued that in the modern world there are two main currents fighting among themselves: the state and the social revolutionary. Bakunin claimed in his work that the nation most capable of developing statehood is the Germans . He tried to prove that the struggle against pan-Germanism is the main task for all ethnic groups of the Slavic and Romanesque tribe, but it is impossible to successfully fight pan-Germanism by creating political counterbalances to it in the form of some great all-Slavic state, etc., since the Germans are on this path , thanks to their state talents and their natural ability for political discipline, they will always prevail.

Contribution to Socialism Theory

Главной задачей социальной революции Бакунин считал разрушение исторических централизованных государств, с заменой их свободной, не признающей писаного закона, федерацией общин, организованных по коммунистическому принципу .

Социалистическая модель Бакунина получила название анархо-коллективизм . В этой социальной системе, как и в марксизме , основная роль отводилась рабочим и крестьянам. Им же на коллективных началах принадлежали средства производства . Предполагалась наличие развитой системы социальной поддержки, таких как равное и бесплатное образование для всех детей [10] . Однако, в отличие от Маркса, Бакунин отрицал необходимость диктатуры пролетариата , считая её угрозой всему делу социальной революции и предпосылкой возврата к авторитаризму .

Главной движущей силой революции Бакунин считал беднейшие слои рабочих и крестьян, а главным способом пропаганды — постоянные мелкие восстания и бунты, называя их пропагандой фактами ( фр. par le fait ) [Прим. 7] [Прим. 8] .

Критика Маркса

Бакунин признавал «гениальность Маркса» и частично принимал взгляды последнего относительно классовой борьбы и природы капитализма . Однако он считал взгляды Маркса односторонними, а его методы — губительными для социальной революции . Особенно резко Бакунин выступал против концепции диктатуры пролетариата , указывая на опасность авторитаризма последней. Бакунин предупреждал [11] :

Если взять самого пламенного революционера и дать ему абсолютную власть, то через год он будет хуже, чем сам Царь.

Original textIf you took the most ardent revolutionary, vested him in absolute power, within a year he would be worse than the Tsar himself.

Memory

В 1918 году имя Бакунина было выбито на Романовском обелиске , установленном в 1914 году у входа в Верхний сад в честь 300-летия дома Романовых , и после переделки ставшим первым монументальным памятником Советской России . Вместо сбитых имён царей и императоров из дома Романовых на плитах обелиска согласно списку, составленному В. М. Фриче , были выдолблены имена «19 выдающихся мыслителей и деятелей борьбы за освобождение трудящихся»; имя Бакунина находилось между именами Прудона и Чернышевского . В 2014 году обелиск подвергся реконструкции ради «возвращения исторического облика», при этом, по мнению специалистов, оригинальный памятник начала XX века, хранивший следы двух эпох, был практически утрачен.

В том же 1918 году в память о Бакунине Покровская улица в Москве была переименована в Бакунинскую улицу .

В 1919 году в Москве на Тургеневской площади по ленинскому плану монументальной пропаганды был установлен памятник Бакунину (скульптор Б. Королев) [12] . Из-за своего странного вида он не был воспринят населением, и в итоге его демонтировали.

Улица Бакунина есть в ряде городов бывшего СССР, в том числе улица Бакунина в Томске и проспект Бакунина в Санкт-Петербурге .

Оценки личности

Случай свел нас с Бакуниным еще в первую пору молодости. Мы знали его не долго, но близко, и видели его в разных положениях жизни. В молодости это был человек не без некоторого блеска, способный озадачивать людей слабых и нервных, смущать незрелых и выталкивать их из колеи. Это была натура сухая и черствая, ум пустой и бесплодно возбужденный. Он хватался за многое, но ничем не овладевал, ни к чему не чувствовал призвания, ни в чем не принимал действительного участия ( Катков М.Н. ) [13]

Compositions

- Гимназические речи Гегеля. Предисловие переводчика (1838)

- О философии (1840)

- Реакция в Германии (1842)

- Кнуто-Германская империя и социальная революция (1871)

- Государственность и анархия (1873)

- Федерализм, социализм и антитеологизм (1867, не закончена)

- Бог и государство (не закончена)

- М. А. Бакунин. Революционный катехизис

- «Исповедь» (Николаю I, написанная по его приказу в Алексеевском равелине Петропавловской крепости)

- в либертарной библиотеке

- Сочинения Бакунина на сайте Lib.ru: Классика

- М. А. Бакунин. Письмо интернационалам Болоньи

- М. А. Бакунин. Личные отношения с Марксом

- М. А. Бакунин Собрание сочинений и писем. 1828—1876 / под ред. и с примеч. Ю. М. Стеклова. — М.: Изд-во Всесоюз. О-ва политкаторжан и ссыльнопоселенцев, 1934—1935

Bibliography

- Катков М. Н. Кто наши революционеры? (Характеристика Бакунина) , 1863.

- А. В. Амфитеатров «Святые отцы революции: М. А. Бакунин» , 1906.

- Блок А. Михаил Александрович Бакунин , 1906.

- В. Черкезов. Значение Бакунина в интернациональном революционном движении , 1915.

- Боровой А. Бакунин , 1926.

- Б. Горев . М. А. Бакунин (К 50-летию со дня смерти)

- Н. М. Пирумова Бакунин ( ЖЗЛ ) (1970) или zip

- Пол Аврич . Бакунин и Нечаев , 1974.

- В. Ф. Пустарнаков. М. А. Бакунин , 1989.

- Плеханов Г. В. Бакунин — глава из книги «Анархизм и социализм»

- Борис Парамонов Сапоги всмятку: бренд «БАКУНИН»

- Дамье В. В. Михаил Бакунин: от социалистического федерализма к анархизму // «Философские науки». 2014. № 7. С.83-102.

- Рябов, Пётр. Человек бунтующий: философия бунта у Михаила Бакунина и Альбера Камю

- Стеклов Ю. М. Михаил Александрович Бакунин. Его жизнь и деятельность. Т. 1-4. — М.-Л., 1926—1927. — 4 т.

- Пирумова Н. М. Михаил Бакунин. Жизнь и деятельность. — М., 1966.

- Пирумова Н. М. Социальная доктрина М. А. Бакунина. — М., 1990.

- М. А. Бакунин: Pro et contra. - 2nd ed., Rev. — СПб: Изд-во РХГА, 2015. — 1050 с.

- Зильберман И. Б. Политическая теория анархизма М. А. Бакунина. Критический очерк. — Л., 1969.

- Дюкло Ж. Бакунин и Маркс. Тень и свет. Per. with french — М., 1975.

- Моисеев П. И. Критика философии М.Бакунина и современность. — Иркутск, 1981.

- Графский В. Г. Бакунин. — М. : Юридическая литература, 1985. — 144 с. — ( Из истории политической и правовой мысли ).

- Мамут Л. С. Этатизм и анархизм как типы политического сознания. Домарксистский период. - M., 1989.

- Ударцев С. Ф. Рукопись М. А. Бакунина «Гамлет» [Статья и публикация неизвестной рукописи (Бакунин М. А. Гамлет)] // Monuments of Culture. Nev Discoveriets = Памятники культуры. Новые открытия. Письменность. Искусство. Археология: Ежегодник (1984) / Академия наук СССР. Научный совет по истории мировой культуры АН СССР. Prev редколлегии — Д. С. Лихачев. Ленинград: Наука, 1986. — 560 с. — С. 55-63.

- Демин В. Н. Бакунин. - M., 2006.

- Кембаев Ж. М. Федералистские идеи М. А. Бакунина относительно объединения народов Европы и всего мира // Право и политика. — № 11. — 2010. — С. 2016—2025.

- Сысоев В. Бакунины.- Тверь: Созвездие, 2002.- 464с.: ил.

See also

- Анархо-коллективизм

- Бакунизм

- Кропоткин, Пётр Алексеевич

- Нечаев, Сергей Геннадиевич

Notes

- ↑ И. О. Сухазанет имел звание генерала от артиллерии и приходился родным братом военному министру — Н. О. Сухозанету

- ↑ В заключении этой статьи было сказано: «… позвольте нам довериться вечному духу, который только потому разрушает и уничтожает, что он есть и неисчерпаемый и вечно творящий источник всякой жизни. Страсть к разрушению есть вместе с тем и творческая страсть» («Die Lust der Zerstörung ist eine schaffende Lust»).

- ↑ В начале января 1845 года Парижская «Судебная газета» опубликовала указы русского правительства, лишающие всех прав и приговаривающие в случае возвращения к ссылке в Сибирь Бакунина и И. Головина .

- ↑ Этот съезд и явился катализатором этого Пражского восстания 1848 года.

- ↑ [1] :Венчание произошло 5 октября 1858 года в градотомской церкви, причем запись в метрической книге свидетельствует о том, что Бакунин, желая быть моложе, уменьшил свой возраст до сорока лет.

- ↑ Отсюда он написал в 1860 году три письма издателям « Колокола », в которых энергично защищал Муравьёва против нападок на него в «Колоколе», причём выставлял его великим государственным человеком и демократом.

- ↑ Отсюда среди его последователей-анархистов образовался термин «парлефетизм».

- ↑ В последние годы своей жизни Бакунин лично попытался организовать крестьянское восстание в северной Италии, для чего предпринял особую экспедицию в Болонью. Затея окончилась полной неудачей, причём сам Бакунин спрятался от итальянских жандармов в возе сена. Неудача этой экспедиции сильно подействовала на Бакунина, показав ему невозможность сколько-нибудь успешного действия при помощи неподготовленных и неорганизованных некультурных народных масс.

Sources

- ↑ Краткая литературная энциклопедия — М. : Советская энциклопедия , 1962. — Т. 1.

- ↑ Пирумова Н. М. Бакунин (1970).

- ↑ А. В. Город Томск. — Томск: Издание Сибирского товарищества печатного дела в Томске, 1912. (недоступная ссылка) . Дата обращения 14 декабря 2014. Архивировано 14 декабря 2014 года.

- ↑ Пирумова Н. М. М. Бакунин или С. Нечаев? // Прометей. — М. : Молодая Гвардия, 1968. — Т. 5 .

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20020623232713/http://www.tuad.nsk.ru/~history/Author/Engl/A/AvricP/avrich-nech.htm Аврич, Пол. Бакунин и Нечаев

- ↑ Бакунин М. Бог и государство. — Типография Издательской Комиссии Московского Совета Солдатских Депутатов, 1917.

- ↑ Пирумова Н. Бакунин . — М. , 1970. — С. 226.

- ↑ Письма М. А. Бакунина к А. И. Герцену и Н. П. Огареву. - SPb. , 1906. — С. 271.

- ↑ Серков А. И. Русское масонство, 1731—2000. Энциклопедический словарь. — М. , 2001. — С. 1205, 1206, 1207, 1210.

- ↑ Revolutionary Catechism , Mikhail Bakunin, 1866

- ↑ Quoted in Daniel Guerin, Anarchism: From Theory to Practice (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970), pp.25-26.

- ↑ moscowwalks.ru

- ↑ Идеология охранительства , с.364

Links

- Бакунины, дворянский род // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). - SPb. , 1891. — Т. IIa. — С. 774—775.

- Бакунины, общественные деятели // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). - SPb. , 1905. — Т. доп. I. — С. 201—203.

- Штейн В. Бакунин, Михаил Александрович // Русский биографический словарь : в 25 томах. - SPb. - M. , 1896-1918.

- Бакунин пробудил у швейцарцев дух анархии . «Наша газета» (Швейцария)

- Могила Михаила Бакунина на сайте «Могилы знаменитостей»

- На сайте Народной Воли

- Жизнь и творчество Бакунина Михаила Александровича

- Бакунин, Михаил Александрович на « Родоводе ». Tree of ancestors and descendants

- Bakunin, Mikhail Alexandrovich // Tomsk from A to Z: A Brief Encyclopedia of the City. / Ed. Dr. East. Sciences N. M. Dmitrienko . - 1st ed. - Tomsk: NTL Publishing House, 2004 .-- S. 25-26. - 440 s. - 3,000 copies. - ISBN 5-89503-211-7 .