Red-headed melanerpes , or red- headed woodpecker [1] ( Latin Melanerpes erythrocephalus ) is a bird from the genus Melanerpes woodpeckers . Distributed in North America in the United States and Canada, where it inhabits various landscapes with woody vegetation, including urban areas. It has a characteristic three-color color with clearly defined borders, making it easy to identify even by amateurs. It feeds mainly on invertebrates and seeds of various plants (including cultivated ones). It nests in hollows, which it plucks in trunks and branches of completely or partially rotten trees. Vulnerable species, the main threats are associated with the improvement of forests, their extinction and fragmentation .

| Red-headed melanerpes |

|

| Scientific classification |

|---|

| No rank : | Bilateral symmetrical |

| Subfamily : | Real woodpeckers |

| Gender: | Melanerpes woodpeckers |

| View: | Red-headed melanerpes |

|

| International scientific name |

|---|

Melanerpes erythrocephalus ( Linnaeus , 1758 ) |

| Area |

|---|

Sedentary populations Migratory populations Occurs only outside the breeding season. |

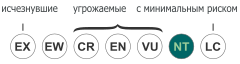

| Security status |

|---|

Close to vulnerableIUCN 3.1 Near Threatened : 22680810 |

|

Content

The size of a large speckled woodpecker : length 19-23 cm, wingspan about 42 cm, weight 56–91 g [2] . The plumage of an adult bird consists of monotonous plots of red, black and white flowers that have clear boundaries. The head, neck, throat and front part of the chest are painted in bright red; in rare cases, you may notice several feathers of orange or yellow. The lower part of the chest, abdomen and undertail are painted white, a thin strip of black feathers in the form of a band is developed at the border of red and white. The shoulders, upper back and hiding wings are black with a blue metallic sheen, the lower back and torso are white. Primary dark brown opaque, minor white. Except for the outer pair, the helmsmen are black-brown with a faint metallic luster; the outer helmsmen are white. Sexual dimorphism manifests itself only in size: females are slightly smaller than males. Young birds are painted more modestly than their parents, although they have the same characteristic pattern. Red color is replaced by gray-brown with dark streaks, brilliant black - black-brown with light streaks. The white plumage plots are the same as in adults, only black spots are noticeable along the posterior edge of the wing [3] .

Range

Red-headed melanerpes is common in North America in the United States and Canada . The population in Canada is estimated at less than 1% of the total population; birds nest in the southern part of the country in Saskatchewan (south of Prince Albert ), Manitoba (areas of lakes Dauphin and Winnipeg ), Ontario (south of Gulf of George Bay ) and very rarely in Quebec (in the valley of the St. Lawrence River ) [4] . In the USA, woodpeckers are found in almost all states from the Atlantic coast to the west to Montana , Colorado and New Mexico (in particular, to the foot of the Rocky Mountains ) [5] . In the east, it is not only in New England [6] and in the very south of Florida [7] .

Partially migratory view. The tendency to migration increases during the years of crop failure of acorns and nuts, while at the time during the years of their abundance, most birds remain wintering in nesting sites or migrate for short distances [8] [9] . The direction of autumn migration is from north to south and from west to east; winter stations are almost everywhere located within the nesting range. Autumn movement lasts from late August to early November with a peak in September, spring - starting from mid-February, reaching its peak in late April and the first half of May [10] [9] .

Habitats

Forest with a predominance of

large -

leaved beech - a typical woodpecker biotope

It inhabits mature flat forests with a predominance of beech , oak or pine , gallery forests , overgrown swamps, light forests , forest-steppes , and fires . He willingly settles in the park zone of settlements and on the outskirts of farmland. In summer, she forage not only in the forest, but also in nearby open landscapes, including mountain meadows, pastures and golf courses . An indispensable condition in summer is the presence of trees with patches of dry rotting wood for nesting and plots of land free from dense undergrowth, and in winter there is an abundance of tall ripe trees [11] . In forests with a high closed crown, as well as with a dense grassy cover, it is rare [9] . In comparison with the Caroline melanterpes, he chooses lighter and more open landscapes with a sparse undergrowth. In areas of intersection with the red-faced melanerpes, the red -headed is concentrated in the gallery forests, while the latter gravitates to farms and forest edges [11] .

Ration

The choice of feed is one of the widest among all woodpecker birds, with the ratio between their categories changing throughout the year: animal food predominates in spring and early summer, vegetable food in winter [11] (plant food takes about two thirds of the total volume per year [2] ) . From animal food in the sources usually appear bugs at all stages of development, ants , wasps , bugs , grasshoppers , crickets , butterflies (including caterpillars), spiders , millipedes , earthworms , small rodents and lizards , as well as eggs and chicks of small birds . Unlike many other members of the family, flying insects become prey much more often than woody ones . The list of plant foods includes seeds of various plants (primarily acorns and beech nuts), grains of corn , cornel berries, wild strawberries , raspberries , blackberries , currants , elderberries and geylussakii , fruits of bird cherry tree of late and virgin , grapes , apple , pear , azimins and pecans . In the midst of winter, when most feeds are not available, the woodpecker switches to maple seeds. Finally, the woodpecker eats tree sap [11] [12] [13] [14] [9] .

Feed Extraction

The most noticeable tactics of obtaining food in the warm season is the so-called “ flycatcher ” method, in which a bird sits on a branch and guards insects flying past (similar feeding behavior is also characteristic of red-faced melanerpes ). When the prey appears, the bird jumps off the priest, grabs it on the fly and returns to its original place. This method alternates with looking for prey on tree branches. Melanerpes examines not only thick branches, but also thin branches, hanging from them like tits . From time to time, the woodpecker descends to the ground and jumps along it, looking for another victim in the rare grass or among the forest litter. The bird aggressively refers to small birds nesting in the neighborhood, including nesting in hollows (for example, the American tree swallow , the Baltimore oriole , the royal and yellow-bellied tyrant , the eastern phoebe, and even the larger crested jelly [15] ). If necessary, it is able to expand too narrow a notch, and then peck the masonry or kill offspring. Slotting the bark to search for insects hiding under it is more typical for winter, when there is no living creature leading to an open lifestyle [12] [11] [16] . Acorns and other fruits are obtained both on trees and from the surface of the earth [17] [18] .

Melanerpes actively stores food for the winter. It hides acorns, nuts and arthropods in crevices of the bark and cavities of natural origin, masking them externally with pieces of bark or slivers. If the prey does not fit in size in its entirety, the woodpecker first chops it to pieces. Some bugs and grasshoppers fall into the “pantry” while they are still alive, while being unable to get out on their own [9] .

The territorial bird, zealously guards the nesting site throughout the year, not only from individuals of the same species, but also from some other birds, including the golden-billed woodpecker and the Caroline melanerpes . On the other hand, the woodpecker is often driven out of its nest by a no less aggressive ordinary starling , which is not an original American bird, but was introduced by man in the 19th century [19] [20] [21] [9] . Nevertheless, observations show that occasionally a bird still shares one tree with the listed birds, as well as the kestrel and bat Indiana night-lamp [20] [22] [23] [24] .

The breeding season is from April to September, most couples manage to breed in the period from May to June. About half of the pairs are laid back again [11] . Monogam ; many couples reunite in the same area after returning from winter migration [25] . A nest is arranged in a hollow, which is hollowed out by a male and a female (most of the work is performed by the male) in a dead tree or a rotten part of a living tree, rarely in an artificial structure (pillar, hedge, house wall, etc.) or a hollow . The construction process usually lasts from 12 to 17 days, but in some cases it can take up to seven weeks [2] [11] . The depth of the nesting chamber is 20–60 cm, the diameter of the notch is 5–6 cm [10] . In clutch, as a rule, from 4 to 7 eggs (in general, from 3 to 10) are white. Both birds incubate alternately for 12-14 days, at night - only the male. Only the chicks that were born are blind and not covered in fluff, are fed by both parents. The ability to fly in most cases appears at the age of 24 to 27 days, sometimes up to 31 days. Having learned to fly, the chicks stay for about 3-4 weeks near the nest, after which they disperse [11] .

In the International Red Book, red-headed melanerpes is recognized as a species that is potentially at risk of extinction (category NT). At the moment, the main threats are the removal of dead trees and branches in urban areas and deforestation for the further use of territories for household needs. Many birds die in a collision with a car [26] . In the second half of the XIX century, the woodpecker was considered an agricultural pest and was persecuted [15] . According to some estimates, the epiphytotia of the so-called “ Dutch elm disease ”, which, in turn, was caused by the appearance of alien fungi from the genus Ophiostoma on the American continent, also contributed to a significant decrease in numbers. In the 1940s - 1960s, the use of DDT in agriculture played a negative role both as a result of a decrease in the number of insects (the main food supply) and as a result of the negative impact on the development of eggs (the shell became fragile and often prematurely destroyed) [27] [15 ] [15 ] ] .

- The beak of a red-headed woodpecker, hollowing the bark of a tree, moves at a speed of 20.9 km / h, which is why the bird’s brain , when the head is thrown back, experiences a negative acceleration g = 10. [28]

- Woody Woodpecker , a well-known cartoon character, is a representative of this particular type of woodpecker.

- ↑ Boehme R. L. , Flint V. E. The Bilingual Dictionary of Animal Names. Birds. Latin, Russian, English, German, French / Ed. ed. Acad. V. E. Sokolova . - M .: Rus. lang., "RUSSO", 1994. - S. 199. - 2030 copies. - ISBN 5-200-00643-0 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 Red-headed Woodpecker - Life History (Neopr.) . All About Birds . Date of treatment January 24, 2016. Archived January 25, 2016.

- ↑ Winkler & Christie, 1995 , p. 198.

- ↑ COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Red-headed Woodpecker Melanerpes erythrocephalus in Canada (neopr.) . COSEWIC (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada) (2007). Date of treatment January 26, 2016. Archived January 27, 2016.

- ↑ Winkler & Christie, 2002 , p. 440.

- ↑ Red-headed Woodpecker Fact Sheet (neopr.) . NYS Department of Environmental Conservation. Date of treatment January 26, 2016. Archived January 27, 2016.

- ↑ Loftin, Robert W. Red-headed Woodpecker Melanerpes erythrocephalus (neopr.) . Florida's breeding bird atlas: A collaborative study of Florida's birdlife . Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (January 6, 2003). Date of treatment January 26, 2016. Archived January 27, 2016.

- ↑ Herkert, 1995 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Luensmann, Peggy. Melanerpes erythrocephalus - Biological data and habitat requirements (neopr.) . Fire Effects Information System . US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (2006). Date of treatment February 7, 2016. Archived on February 7, 2016.

- ↑ 1 2 Smith et al., 2000 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Winkler & Christie, 2002 , p. 441.

- ↑ 1 2 Winkler & Christie, 1995 , p. 199.

- ↑ Wiebe, 2006 .

- ↑ Gorman, 2014 , p. 111.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Red-headed Woodpecker ( Melanerpes erythrocephalus ) Species Guidance (neopr.) . Wisconsin Bird Conservation Initiative All Bird Conservation Plan . Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Bureau of Natural Heritage Conservation. Date of treatment February 7, 2016. Archived on February 8, 2016.

- ↑ Conner et al., 1994 .

- ↑ Cypert & Webster, 1948 .

- ↑ Sork et al., 1983 .

- ↑ Ingold, 1989 .

- ↑ 1 2 Ingold, 1990 .

- ↑ Ingold, 1994.B.

- ↑ Ingold, 1994.A.

- ↑ Kurta et al., 1993 .

- ↑ Reller, 1972 .

- ↑ Ingold, 1991 .

- ↑ Melanerpes erythrocephalus (neopr.) . The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species . International Union for Conservation of Nature. Date of treatment February 27, 2016. Archived February 27, 2016.

- ↑ Adams & Wenger, 2011 .

- ↑ About the birds from the Guinness Book of Records

- Adams, Raymond J .; Wenger, Torrey. Red-headed Woodpecker ( Melanerpes erythrocephalus ) / Chartier, AT; Baldy, JJ; Brenneman, JM, eds // The Second Michigan Breeding Bird Atlas. Kalamazoo Nature Center. Kalamazoo, Michigan. - 2011.

- Conner, Richard N .; Jones, Stanley D .; Jones, Gretchen D. Snag condition and woodpecker foraging ecology in a bottomland hardwood forest // The Wilson Bulletin. - 1994. - Vol. 106, no. 2. - P. 242-257.

- Cypert, E .; Webster, BS Yield and use by wildlife of acorns of water and willow oaks // Journal of Wildlife Management. - 1948. - Vol. 12, no. 3. - P. 227-231.

- Gorman, Gerard. Woodpeckers of the World: The Complete Guide. - Bloomsbury, 2014 .-- 448 p. - ISBN 978-1408147153 .

- Herkert, James R. An analysis of midwestern breeding bird population trends: 1966-1993 // The American Midland Naturalist. - 1995. - Vol. 134, no. 1. - P. 41-50.

- Ingold, Danny J. Nesting phenology and competition for sites among red-headed and red-bellied woodpeckers and European starlings // The Auk. - 1989. - Vol. 106. - P. 209-217.

- Ingold, Danny J. Simultaneous use of nest trees by breeding red-headed and red-bellied woodpeckers and European starlings // The Condor. - 1990. - Vol. 92, no. 1. - P. 252-253.

- Ingold, Danny J. Nest-site fidelity in red-headed and red-bellied woodpeckers // The Wilson Bulletin. - 1991. - Vol. 103, no. 1. - P. 118-122.

- Ingold, Danny J. Influence of nest-site competition between European starlings and woodpeckers // The Wilson Bulletin. - 1994.A. - Vol. 106, no. 2. - P. 227-241.

- Ingold, Danny J. Nest-site characteristics of red-bellied and red-headed woodpeckers and northern flickers in East-Central Ohio // Ohio Journal of Science. - 1994.B. - Vol. 94, no. 1. - P. 2-7.

- Kurta, Allen; Kath, Joseph; Smith, Eric L .; Foster, Rodney; Orick, Michael W .; Ross, Ronald. A maternity roost of the endangered Indiana bat ( Myotis sodalis ) in an unshaded, hollow, sycamore tree ( Platanus occidentalis ) // The American Midland Naturalist. - 1993. - Vol. 130, no. 2. - P. 405–407.

- Reller, Ann Willbern. A comparison of some aspects of behavioral ecology of red-headed and red-bellied woodpeckers // The American Midland Naturalist. - 1972. - Vol. 88, no. 2. - P. 270-290.

- Smith, Kimberly G .; Withgott, James H .; Rodewald, Paul G. Red-headed woodpecker - Melanerpes erythrocephalus // The birds of North America. - 2000. - No. 518. - P. 1–27.

- Sork, Victoria L .; Stacey, Peter; Averett, John E. Utilization of red oak acorns in non-bumper crop year // Oecologia. - 1983. - Vol. 59. - P. 49-53.

- Wiebe, Karen L .; Koenig, Walter D .; Martin, Kathy. Evolution of clutch size in cavity-excavating birds: the nest site limitation hypothesis revisited // The American Naturalist. - 2006. - Vol. 167, no. 3. - P. 343-353.

- Winkler, Hans; Christie, David; Nurney, David. Woodpeckers: An Identification Guide to the Woodpeckers of the World. - Houghton Mifflin, 1995 .-- ISBN 0395720435 . (eng.)

- Winkler, Hans; Christie, David A. Family Picidae (Woodpeckers) / del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J., eds .. - Handbook of the birds of the world. - Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 2002 .-- T. 7: Jacamars to Woodpeckers. - ISBN 978-8487334375 . (eng.)