Alpine jackdaw [1] ( lat. Pyrrhocorax graculus ) is a bird of the corvidae family . It inhabits alpine meadows and exposed cliffs in the mountainous regions of Eurasia and North Africa at an altitude of 1260 to 5000 m above sea level [2] . The meeting of a flock of these birds near the top of Everest not only indicates that, if necessary, the bird can fly even higher, but also confirms the thesis that it is the highest mountain vertebrate organism in the world.

| Alpine jackdaw | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International scientific name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pyrrhocorax graculus ( Linnaeus , 1766) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Security status | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The size of a jackdaw , this bird has long been considered its close relative, but molecular studies at the beginning of the 21st century have refuted this assumption. Closest to the alpine jackdaw is the nestle . Both birds have a shiny black plumage and red legs, but on an alpine jackdaw the beak is yellow and almost straight, and on the clawfish red and sickle-shaped. The vocalization of both birds is also markedly different. The jackdaw is distinguished by a very fast and maneuverable flight; it spends most of its life in flocks of hundreds or more birds [3] .

In the summer it feeds on insects and other invertebrates, in winter the fruits of various plants. In search of food, he often visits ski resorts, where he spins near hotels and trash cans. Not afraid of man. It nests in inaccessible places on rocky cornices, in crevices and steep depressions, sometimes in niches of facades of unused buildings. Nest of twigs, grass and pieces of wool. In clutch 3-5 eggs of creamy white, cream or greenish background and superficial spots.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature considers the species as a whole prosperous, while in a number of regions of Europe its number has significantly decreased due to anthropogenic factors. The most serious potential threat to livelihood is global warming .

Content

Systematics

The first scientific description of an alpine jackdaw appeared in 1766 in the twelfth edition of the " System of Nature " by Karl Linnaeus ; the author gave it the name Corvus graculus , placing it in the same group as other corvus birds [4] . A few years later in 1771, the British ornithologist Marmadyuk Tanstell described the new genus Pyrrhocorax and included two species in it: the described one and the harp [5] .

For a long time, it was believed that the closest relatives of both birds are typical crows ( Corvus ), especially the jackdaw and Daurian jackdaw [6] . A study of DNA and cytochrome b , conducted by a group of Swedish and American scientists in the 2000s, showed that Pyrrhocorax along with the rocket-tailed magpie ( Temnurus temnurus ) are much older than these birds and are on the phylogenetic tree of the root group of the corvidae [7] .

The species is represented by two subspecies, one of which ( P. g. Graculus ) is widespread in Europe , North Africa , Asia Minor , the Caucasus and Iran ; the second ( P. g. digitatus ) - in the mountain systems of Central Asia and Southern Siberia . Variability is manifested in general sizes: the eastern subspecies is noticeably larger than the western [8] . The generic name Pyrrhocorax is a combination of two ancient Greek words: πύρρος ("fiery red") and κόραξ ("raven"). Species name graculus - Latin name for jackdaw [9]

Description

Appearance

Slightly smaller than the closely related nests: length 37–39 cm, wingspan 75–85 cm, weight 188–252 g [10] . Both species partially share common morphological characteristics, including shiny black plumage, dark iris and red legs [11] . The most noticeable difference between the two birds is the shape and color of the beak: in the alpine jackdaw it is shorter and more straightened, painted in yellow, while in the claws it is elongated, sickle-shaped and has a red color. To a lesser extent, the daw is distinguished by a longer tail and short narrow wings [12] . External sexual differences appear only in barely noticeable larger sizes of males. In birds of the first year of life, the plumage is dull black, the beak is yellowish, legs are brown [11] .

The flight is light and maneuverable, alternating with shallow flapping of wings and gliding in the ascending currents of warm air [10] . High in the air, it differs from the clawfish in the less rectangular shape of the wings and a long wedge-shaped tail. Comparison with other birds, the differences are even more pronounced: an ordinary jackdaw is noticeably smaller, moreover, its color contains gray tones without shine [10] .

Voice

Vocalization is very diverse. At least 90% of sounds made by an alpine daw do not look like sounds of a naughty girl. The most frequent scream, including that made by many birds at the same time, is a high, rolling "cirrrr", similar to the hum of electric wires. Another characteristic cry is a piercing short whistle with an accent on the last syllable, transmitted as “ia” or “cirrra”, not as harmonious as in the first case. The alarm is similar to the previous cry, but deeper and more intense. In rare cases, screams like a naughty girl [3] .

Distribution

It inhabits the mountainous regions of the Palearctic from Iberia east to western China . In Europe, distributed in almost all major mountain systems: Pyrenees , Jura , Alps , Apennines , Stara Planina and the Rhodope Mountains , as well as on the islands of Corsica and Crete . According to some reports, nests in the southern Carpathians . The only range in Africa belongs to the Atlas Mountains in Morocco [8] .

In Western Asia, it is distributed in the east of the Pontic Mountains , in various parts of the Taurus Mountains , the Greater and Lesser Caucasus , the Armenian Highlands , Elburz , and Zagros . The jackdaw is widely represented in the mountain systems and ridges of Central Asia and the south of Siberia: southeastern and southern Altai , Dzhungarskiy Alatau , Tien Shan to the east to Ketmen and Khan Tengri , Pamir-Alai , Hindu Kush , Kunlun , Altıntag , Nanshan , Tsilyanshan , Tibetan Highlands and the Himalayas [8] .

According to the Guinness Book of Records , this is the highest bird: in 1924 a small flock of jackdaws accompanied a group of British climbers at an altitude of 8,200 m (26,900 ft ) above sea level when climbing Mount Everest [13] [14] . It also breeds higher than any other bird: one of the nests of the alpine jackdaw was found at an altitude of 6500 m above sea level [15] . As a rule, the bird still lives much lower: in Europe from 1260 to 2880 m, in Morocco from 2880 to 3900 m, in the Himalayas from 3500 to 5000 m above sea level [11] . The nest arranges in hard-to-reach rocky crevices [16] ; it obtains food in alpine meadows and other open landscapes. In winter, it often concentrates around settlements, ski resorts and hotels [10] , where it feeds on food waste [6] .

Despite the harsh climate, the alpine jackdaw leads a sedentary lifestyle, although in search of food it often makes vertical wanderings. In the Moroccan population, cases of sudden dispersal far beyond the boundaries of the habitat are known: birds established a small colony in southern Spain near the city of Malaga and were seen in Gibraltar , in the former Czechoslovakia , Hungary and Cyprus [11] .

Nutrition

Ration

Meals mixed with seasonal preferences. In spring and summer, it feeds on various invertebrates that it obtains in meadows: bugs (including Selatosomus aeneus and Otiorhynchus morio ), snails , grasshoppers , caterpillars , and larvae of flies . In autumn, winter and early spring, he switches to plant foods — fruits of the southern skeleton , buckthorn buckthorn [6] , rose hips , etc. Whenever possible, he eats the fruits of cultivated plants - apple trees , pears , and grapes [17] . One work provides evidence that a flock of jackdaws fed on gynoecium and spring saffron petals ( Crocus vernus albiflorus ) - possibly as a source of carotenoids [18] [19] .

In addition to natural resources, the alpine jackdaw benefits from human activities. In winter, flocks of birds often feed on ski resorts, picnic areas, food waste dumps and near hotels. In places where people visit bird flocks are more numerous, with a significant percentage of young animals. Especially a lot of young birds near garbage containers [20] . This bird, like the nestling bird, makes food supplies - hides it in the crevices of rocks and disguises it with pieces of rock [21] .

Feed Extraction

Food is always obtained by established groups (schools), more numerous in the cold season. Given limited resources, adult birds and males receive priority access to food [22] . Specific climatic conditions, availability and quality of feed can affect the vertical movements of birds. In summer, jackdaws usually stay above the forest border , and in winter they either descend along the slopes or concentrate in places visited by people [17] . Autumn movement begins with the first snowfall - in the daytime, birds seek food in the valleys, and again go up to the shelter. In March and April, when there is very little food, the number of visits to cultural landscapes reaches its highest value [17] . The distance of the daily route from the resting place to the food base can reach 20 km with a height difference of 1600 m. In the Alps, where the ski business is well developed, most birds remain close to the nesting sites [10] .

In the areas of intersection of the ranges of alpine jackdaws and nests, both species can form mixed flocks. The intersection of the diet is insignificant: as observations in the Alps show, in winter the klushka eats almost exclusively goose onions dug from the ground, while the alpine jackdaw prefers berries and rose hips. In June, the nestling switch to caterpillars, while the alpine daw begins to look for pupae of mosquito-centipedes . Later in the summer, when the proportion of mosquito-centipedes and beetles in the diet of the nest is growing, the jackdaw catches grasshoppers in large quantities [23] . In November, in the Himalayas, the alpine jackdaw concentrates in the plantings of juniper , where it feeds on its berries. At the same time, the nestling dwellers living in the neighborhood extract food from the earth on terraced lawns within settlements [24] .

Reproduction

Alpine jackdaw is a social monogamous bird that forms a mating union for several years and is with a partner even at the end of the breeding season [22] . Propagated by isolated pairs, starting in May. Several pairs can nest in close proximity to each other, but the colonial breeding method as such is not developed [11] . The nest is loose, composed of twigs and roots intertwined with grass stems and wool, built in crevices and on rocky ledges, occasionally on the facades of abandoned buildings. In the clutch there are 3-5 eggs with a shiny shell of creamy white, cream or greenish color with superficial spots [11] , an average size of 33.9 × 24.9 mm [25] .

The female incubates from the first egg for 14-21 days [10] . The chicks that were born, unlike the chicks chicks, are covered with thick down [26] , leave the nest after 29-31 days and join the flocks [10] . Both parents feed offspring, including some time after acquiring the ability to fly. In a flock, other adult birds can feed the flying chicks [11] .

Like the eggs of other birds, alpine jackdaw eggs contain the pores necessary for the respiration of the embryos. However, in this species they are much narrower than in birds of flat landscapes, which contributes to the retention of moisture during evaporation under very low atmospheric pressure [27] . Embryo blood also has a higher hemoglobin content, which is necessary for oxygen binding and respiration [28] .

According to observations in the Italian Alps, the location of the nest at the alpine jackdaw is very diverse in comparison with the location of the nest of nests. If the latter uses only rocky cornices, then the jackdaw also occupies cracks, grooves, and even unused structures of artificial origin [11] [23] [29] . The breeding times of the described species are shifted forward by about a month in comparison with the moth, while the nesting biology of both species is similar [23] .

Natural Enemies

Feathered predators primarily hunt the alpine daw: peregrine falcon , golden eagle , eagle owl . A raven [30] [31] [32] [33] was seen behind the ruin of bird nests. One scientific article describes a unique observation: in Pakistan's Khanjerab Park, five or six birds circled in front of a lonely fox , sinking to the ground in front of her nose and taking off again. The authors of the article believe that in this way the birds worked out the tactics of salvation from the animal, which is also well known for hunting these birds, or drove it away from a favorite glade [34] .

Famous avian parasites: fleas Ceratophyllus vagabunda , Frontopsylla frontalis and Frontopsylla laetus [35] , tapeworm Choanotaenia pirinica [36] and various lice from the genera Brueelia , Menacanthus and Philopterus [37] .

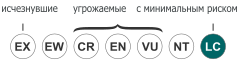

Conservation Status

According to the estimates of the International Union for Conservation of Nature , the total area of the distribution area of the Alpine jackdaws is about 3.5 million square kilometers, and the approximate number is from 796 to 3720 thousand heads [2] . The condition of the species as a whole is considered stable, its status in the international Red Book is the least risk taxon (category LC) [2] .

During the last ice age , the bird range was much wider, reaching southern Italy in the south [38] . Numerous relic populations remained after it, which finally disappeared only in the last centuries: for example, until the 19th century, alpine jackdaws nested in the Polish Tatras [39] . Petrified remains of birds were discovered in the Canary Islands [40] . In Bulgaria, the number of birds decreased from about 77 pairs in the 1950-1981s to 14 in 1996-2006 and continues to decline. It is believed that this local degradation is associated with increased grazing, because of which tall grass is replaced by low-growing shrub vegetation [41] . Alpine meadows can be used for the construction of ski slopes and camp sites, which also reduces the area on which poultry feed themselves [42] . Observations show that where human activity is minimal, the number of jackdaws remains stable or even grows. On the contrary, in areas with intensive agriculture, such as in the UK , French Brittany , southwest Portugal and Scotland , birds cease to nest [43] .

In some places, an alpine jackdaw may suffer from the presence of pesticides and toxic heavy metals in the soil, torrential rains and anxiety from people, including intentional destruction [41] . The potential danger is global warming , which reduces acceptable habitats [44] .

Notes

- ↑ Boehme R. L. , Flint V. E. The Bilingual Dictionary of Animal Names. Birds. Latin, Russian, English, German, French / Ed. ed. Acad. V. E. Sokolova . - M .: Rus. lang., "RUSSO", 1994. - S. 472. - 2030 copies. - ISBN 5-200-00643-0 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 Pyrrhocorax graculus . The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species . International Union for Conservation of Nature. Date of treatment June 9, 2016. Archived June 9, 2016.

- ↑ 1 2 Mullarney et al., 1998 , p. 334.

- ↑ Linnaeus, 1766 , p. 1766.

- ↑ Tunstall, 1771 , p. 2.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Goodwin, 1976 , p. 151-158.

- ↑ Ericson et al., 2005 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 Stepanyan, 2003 , p. 407.

- ↑ Jobling, 1992 , p. 97, 196.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Snow & Perrins, 1998 , p. 1464-1466.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Madge & Burn, 1994 , p. 132-133.

- ↑ Koblik, 2001 , p. 320.

- ↑ McWhirter, 1978 , p. 83.

- ↑ Silverstein & Silverstein, 2003 , p. 17.

- ↑ Bahn & Ab, 1974 .

- ↑ Baumgart, 1967 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 Laiolo et al., 2001 .

- ↑ Glutz von Boltzheim et al., 2000 .

- ↑ McKibbin & Bishop, 2008 .

- ↑ Delestrade, 1994 .

- ↑ Wall, 1990 , p. 306.

- ↑ 1 2 Delestrade & Stoyanov, 1995 .

- ↑ 1 2 3 Rolando & Laiolo, 1997 .

- ↑ Laiolo, 2003 .

- ↑ Harrison, 1982 , p. 316.

- ↑ Starck & Ricklefs, 1998 , p. 7.

- ↑ Rahn & Ar, 1974 .

- ↑ Black & Snyder, 1980 .

- ↑ Blanco et al., 1997 .

- ↑ A year in the life of Choughs . Birdwatch Ireland. Date of treatment June 9, 2016. Archived June 9, 2016.

- ↑ Other Cornish Crows . Operation Chough, conservation project at Paradise Park, Hayle. Date of treatment June 9, 2016. Archived June 9, 2016.

- ↑ Rolando et al., 2001 .

- ↑ Blanco & Tella, 1997 .

- ↑ Blumstein & Foggin, 1993 .

- ↑ Rothschild & Clay, 1961 .

- ↑ Georgiev et al., 1987 .

- ↑ Kellogg & Paine, 1914 .

- ↑ Yalden & Albarella, 2009 , p. 44–46.

- ↑ Tomek & Bocheński, 2005 .

- ↑ Reyes, 2007 .

- ↑ 1 2 Stoyanov et al., 2008 .

- ↑ Rolando & Patterson, 1993 .

- ↑ Pain & Dunn, 1996 .

- ↑ Sekercioglu et al., 2008 .

Literature

- Koblik, E. A. Variety of birds (based on the materials of the exposition of the Zoological Museum of Moscow State University. - Publishing House of Moscow State University, 2001. - T. Part 4 (Vorobinobraznye detachment - continued). - 380 pp. - ISBN 5-211-04072-4 .

- Stepanyan, L. S. Synopsis of the ornithological fauna of Russia and adjacent territories. - Moscow: Academic Book, 2003 .-- S. 166-167. - ISBN 5-94628-093-7 .

- Bahn, H .; Ab, A. The avian egg: incubation time and water loss // The Condor. - 1974. - Vol. 76, no. 2. - P. 147-152. - DOI : 10.2307 / 1366724 .

- Baumgart, W. Alpendohlenkolonien in Felsschächten des Westbalkan // Journal für Ornithologie. - 1967. - Vol. 108, no. 3. - P. 341-345. - DOI : 10.1007 / BF01671883 .

- Black, Craig Patrick; Snyder, Gregory K. Oxygen transport in the avian egg at high altitude // American Zoologist. - 1980. - Vol. 20, no. 2. - P. 461-468. - DOI : 10.1093 / icb / 20.2.461 .

- Blanco, Guillermo; Fargallo, Juan A .; Tella, José Luis; Cuevas Jesús A. Role of buildings as nest-sites in the range expansion and conservation of choughs Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax in Spain // Biological Conservation. - 1997. - Vol. 79, no. 2-3. - P. 117—122. - DOI : 10.1016 / S0006-3207 (96) 00118-8 .

- Blanco, Guillermo; Tella, José Luis. Protective association and breeding advantages of choughs nesting in lesser kestrel colonies // Animal Behavior. - 1997. - Vol. 54, no. 2. - P. 335—342. - DOI : 10.1006 / anbe.1996.0465 .

- Blumstein, Daniel T .; Foggin, J. Marc. Playing with fire? alpine choughs play with a Tibetan red fox // Journal, Bombay Natural History Society. - 1993. - Vol. 90. - P. 513-515.

- Delestrade, Anne. Factors affecting flock size in the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus // Ibis. - 1994. - Vol. 136. - P. 91-96. - DOI : 10.1111 / j.1474-919X.1994.tb08135.x .

- Delestrade, Anne; Stoyanov, Georgi. Breeding biology and survival of the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus // Bird Study. - 1995. - Vol. 42, no. 3. - P. 222-231. - DOI : 10.1080 / 00063659509477171 .

- Ericson, Per GP; Jansén, Anna-Lee; Johansson, Ulf S .; Ekman, Jan. Inter-generic relationships of the crows, jays, magpies and allied groups (Aves: Corvidae) based on nucleotide sequence data // Journal of Avian Biology. - 2005. - Vol. 36, no. 3. - P. 222-234. - DOI : 10.1111 / j.0908-8857.2001.03409.x .

- Georgiev BB; Kornyushin, VV .; Genov, T. Choanotaenia pirinica sp. n (Cestoda, Dilepididae), a parasite of Pyrrhocorax graculus in Bulgaria // Bulletin of Zoology. - 1987. - Vol. 3. - P. 3-7.

- Glutz von Boltzheim, UN; Borleis, F .; Riggenbach, A. Alpine Choughs feeding on crocus flowers and the physiological significance of this behavior // Ornithologische Beobachter. - 2000. - Vol. 97. - P. 303-306.

- Goodwin, Derek. Crows of the World. - Natural History Museum Publications, 1976. - 360 p. - ISBN 978-0565007713 .

- Jobling, James A. A Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. - United States: Oxford University Press, 1992. - ISBN 0198546343 .

- Harrison, Colin. A Field Guide to Nests, Eggs, Nestlings of British and European Birds. - Viking Pr, 1982. - 384 p. - ISBN 978-0002192491 .

- Kellogg, VL; Paine, JH Mallophaga from birds (mostly Corvidae and Phasianidae) of India and neighboring countries // Records of the Indian Museum. - 1914. - Vol. 10 .-- P. 217-243.

- Laiolo, Paola; Rolando, Antonio .; Carisio, Lorendana. Winter movements of the Alpine Chough: implications for management in the Alps // Journal of Mountain Ecology. - 2001. - Vol. 6. - P. 21-30.

- Laiolo, Paola. Ecological and behavioural divergence by foraging Red-billed Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and Alpine Choughs P. graculus in the Himalayas // Ardea. - 2003. - Vol. 91, no. 2. - P. 273-277.

- Linnaeus, Carlos. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio duodecima: [ lat. ] . - Holmiae: Laurentii Salvii, 1766.

- Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary. Crows and Jays: A Guide to the Crows, Jays and Magpies of the World. - Christopher Helm Publishers Ltd, 1994 .-- 216 p. - ISBN 978-0713639995 .

- McKibbin, René; Bishop, Christine A. Feeding observations of the western Yellow-breasted Chat in the south Okanagan valley British Columbia, Canada during a seven-year study period // British Columbia Birds. - 2008 .-- Vol. 18. - P. 24-25.

- McWhirter, Norris. Guinness Book of World Records 1978.- Sterling Publishing Co., 1978.- 704 p. - ISBN 978-0553112559 .

- Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter. Collins Bird Guide: The Most Complete Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. - Harpercollins Pub Ltd, 1998. - 400 p. - ISBN 0-00-219728-6 .

- Pain, Debbie; Dunn, Euan. The effects of agricultural intensification upon pastoral birds: lowland wet grasslands (The Netherlands) and transhumance (Spain) // Wader Study Group Bulletin. - 1996. - Vol. 81. - P. 59-65.

- Rahn, H .; Ar, A. The avian egg: incubation time and water loss // The Condor. - 1974. - Vol. 76, no. 2. - P. 147-152. - DOI : 10.2307 / 1366724 .

- Reyes, Juan Carlos Rando. New fossil records of choughs genus Pyrrhocorax in the Canary Islands: hypotheses to explain its extinction and current narrow distribution // Ardeola. - 2007. - Vol. 54, no. 2. - P. 185-195.

- Rolando, Antonio; Laiolo, Paola. A comparative analysis of the diets of the chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and the alpine chough Pyrrhocorax graculus coexisting in the Alps // Ibis. - 1997. - Vol. 139, no. 2. - P. 388-395. - DOI : 10.1111 / j.1474-919X.1997.tb04639.x .

- Rolando, Antonio; Caldoni, Riccardo; De Sanctis, Augusto; Laiolo, Paola. Vigilance and neighbor distance in foraging flocks of red-billed choughs, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax // Journal of Zoology. - 2001. - Vol. 253, no. 2. - P. 225-232. - DOI : 10.1017 / S095283690100019X .

- Rolando, Antonio; Patterson, Ian James. Range and movements of the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus in relation to human developments in the Italian Alps in summer // Journal of Ornithology. - 1993. - Vol. 134, no. 3. - P. 338—344. - DOI : 10.1007 / BF01640430 .

- Rothschild, Miriam; Clay, Theresa. Fleas, Flukes and Cuckoos: A Study of Bird Parasites. - Arrow Books Ltd, 1961. - 304 p.

- Sekercioglu, Cagan H; Schneider, Stephen H .; Fay, John P. Loarie; Scott R. Climate change, elevational range shifts, and bird extinctions // Conservation Biology. - 2008 .-- Vol. 22, no. 1. - P. 140-150. - DOI : 10.1111 / j.1523-1739.2007.00852.x .

- Silverstein Alvin; Silverstein, Virginia. Nature's Champions: The Biggest, the Fastest, the Best. - Dover Children's Science Books, 2003. - 64 p. - ISBN 0-486-42888-5 .

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M. The Birds of the Western Palearctic. - Oxford University Press, 1998 .-- 1830 p. - ISBN 978-0198540991 .

- Starck, J. Matthias; Ricklefs, Robert E. Avian Growth and Development: Evolution within the Altricial-Precocial Spectrum . - Oxford University Press, 1998 .-- 456 p. - ISBN 978-0195106084 .

- Stoyanov, Georgi P .; Ivanova, Teodora; Petrov, Boyan P .; Gueorguieva, Antoaneta. Past and present breeding distribution of the alpine chough (Pyrrhocorax graculus) in western Stara Planina and western Predbalkan Mts. (Bulgaria) // Acta Zoologica Bulgarica. - 2008 .-- Vol. 2. - P. 119-132.

- Tomek, Teresa; Bocheński, Zygmunt. Weichselian and Holocene bird remains from Komarowa Cave, Central Poland // Acta zoologica cracoviensia. - 2005. - Vol. 48A, no. 1-2. - P. 43-65.

- Tunstall, Marmaduke. Ornithologia Britannica: seu Avium omnium Britannicarum tam terrestrium, quam aquaticarum catalogus, sermone Latino, Anglico et Gallico redditus: [ lat. ] . - London: J. Dixwell, 1771.

- Wall, Stephen B. Vander. Food Hoarding in Animals. - University Of Chicago Press, 1990 .-- 453 p. - ISBN 978-0226847344 .

- Yalden, Derek; Albarella, Umberto. The History of British Birds. - Oxford University Press, 2009 .-- 288 p. - ISBN 978-0199217519 .

Links

- Vertebrates of Russia: Alpine Jackdaw

- Video, audio and photo materials about the appearance of the Alpine Jackdaw in the database The Internet Bird Collection .