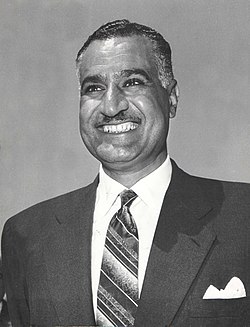

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein ( Arabic جمال عبد الناصر حسين ; January 15, 1918 , Alexandria - September 28, 1970 , Cairo ) - Egyptian revolutionary, statesman and political figure, the second president of Egypt (1956-1970). He led the overthrow of King Farouk in 1952 and in the same year began a far-reaching land reform. Having survived the assassination attempt of a member of the Muslim Brotherhood in 1954, he defeated this organization, put President Mohammed Nagib under house arrest and became the head of the country, officially taking office as president after the 1956 referendum.

| Gamal Abdel Nasser | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arab. جمال عبد الناصر | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | position established | ||||||

| Successor | Anwar Sadat | ||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | Mohammed Nagib | ||||||

| Successor | Anwar Sadat | ||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | Muhammad Sidki Suleiman | ||||||

| Successor | Mahmoud Fawzi | ||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | Mohammed Nagib | ||||||

| Successor | Ali Sabri | ||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | Mohammed Nagib | ||||||

| Successor | Mohammed Nagib | ||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | Gamal Salem | ||||||

| Successor | Gamal Salem | ||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | |||||||

| Successor | Gamal Salem | ||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | |||||||

| Successor | Zakaria Mohi al-Din | ||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | Mohammed Nagib | ||||||

| Successor | position abolished | ||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | Josip Broz Tito | ||||||

| Successor | Kenneth Kaunda | ||||||

| |||||||

| Predecessor | Haile Selassie I | ||||||

| Successor | Kwame Nkrumah | ||||||

| Birth | January 15, 1918 Alexandria , Sultanate of Egypt | ||||||

| Death | September 28, 1970 (52 years old) Cairo , United Arab Republic | ||||||

| Burial place | Gamal Abdel Nasser Mosque, Cairo | ||||||

| Father | Abdel Nasser Hussein | ||||||

| Mother | Fahima Hamad | ||||||

| Spouse | Tahya Kazem | ||||||

| Children | sons: Khalid, Abdel Hakim and Abdel Hamid daughters: Hoda and Mona | ||||||

| The consignment | Arab Socialist Union | ||||||

| Education | Royal Military Academy | ||||||

| Religion | Islam ( Sunnism ) | ||||||

| Autograph | |||||||

| Awards | |||||||

| Military service | |||||||

| Years of service | 1938–1952 | ||||||

| Type of army | |||||||

| Rank | |||||||

| Battles | Arab-Israeli war (1947-1949) | ||||||

The nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956 led to the Suez Crisis and significantly increased its popularity in Egypt and in the Arab world. Adhering to the ideology of pan-Arabism , in 1958-1961 he headed the United Arab Republic as part of Egypt and Syria. In 1962, he began to implement broad socialist reforms and modernization of the country. Despite the failure of pan-Arabism in the international arena, by 1963 Nasser’s supporters managed to come to power in several Arab countries, he himself was drawn into a civil war in North Yemen . In March 1965, he was re-elected to the post of head of state in an election on no alternative basis. After the defeat of Egypt in the Six Day War with Israel in 1967, he resigned, however, after mass demonstrations in his own support, he canceled the decision. By 1968, he took the post of prime minister, started a war of attrition with Israel in order to recapture the lost lands, launched the process of depoliticization of the armed forces and liberal political reforms. He died in 1970 of a heart attack, which caused a wide response in the Arab world: about 5 million people attended the funeral of the Egyptian president in Cairo.

Nasser remains a cult figure in the Arab world, revered, in particular, for the pursuit of social justice and Arab unity, the policy of modernization and anti-imperialism . The boom of culture and industrialization fell on the reign of this Egyptian president: the Aswan Dam and the industrial city of Heluan were built. Nasser has been criticized for authoritarianism, populism, human rights violations and the inability to build a civil society in the country.

Early life

Gamal Abdel Nasser was born on January 15, 1918 in the Alexandrian district of Bakos in the family of the postal worker Abdel Nasser and his wife Fahim [2] , who married in 1917. He was the first son in the family, then two of his brothers were born - Izz al-Arab, which means "the pride of the Arabs" [3] , and al-Liti [2] . Due to the nature of the father’s work, the family often moved and in 1923 settled in the city of Hatatba, 43 kilometers from Cairo. In Khatatbe, Gamal went to kindergarten for the children of railway workers, until in 1924 he was sent to his paternal uncle in Cairo, where he attended elementary school [4] . In April 1926, the mother of the boy died during childbirth [5] [6] , which deeply influenced him [7] . In 1928, he moved to Alexandria to his maternal grandmother, where he continued his education [6] [7] . The following year, Nasser was enrolled in a boarding school in Helwan, then returned to Alexandria, where he entered high school and began to help his father in [6] [7] . Here, in 1930, he was first involved in political activism: after the police tried to disperse a demonstration against colonialism, gathered because Prime Minister Ismail Sidki canceled the 1923 constitution [7] , he joined the rally without knowing the reasons for the protest [8 ] , was arrested and spent the night at the police station [9] , until his father rescued the young man from there [6] .

In 1933, after his father was transferred to Cairo, Nasser moved there with him [10] . On November 13, 1935, the young man led the students' protest against the statement by British Foreign Secretary Samuel Hore about the lack of prospects for restoring the 1923 constitution [7] . The demonstration was suppressed by the authorities: two people were killed [9] , Gamal was easily hit in the head with a police bullet, which honored him in the press [11] . On December 12, the new King Farouk announced the restoration of the old fundamental law [7] .

Being actively involved in political activities, in his last year at school, Nasser attended her only 45 days [12] [13] . He strongly condemned the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936, which confirmed the presence of British military bases in the country, despite the support of the agreement by almost all political forces in Egypt. Political activity in the state began to decline, and Nasser resumed his studies [12] , graduating in 1936 [7] .

Development of political views

Descending from a poor family, Nasser developed discontent towards the local elite throughout his life [14] . In Cairo, where Nasser lived alongside the , he read a lot, in particular, he became acquainted with the Quran , the Hadith of the Prophet Muhammad , the biographies of his companions [15] , the biographies of the nationalist leaders Napoleon , Ataturk , Bismarck , Garibaldi, and the Churchill autobiography Churchchild. » [7] [9] [16] [17] .

Nasser was greatly influenced by Egyptian nationalism , professed by activist Mustafa Kamil , poet Ahmed Shawki [15] and Nasser instructor at the military academy, , to whom he expressed appreciation in a 1961 newspaper interview [18] . Nasser attached particular importance to the novel “The Return of the Spirit” by Taufik al-Hakim , later calling him inspired by the 1952 revolution. In this work, the author wrote about the Egyptians' need for a leader who would express their aspirations [9] [16] .

Military career

In 1937, Nasser applied for admission to the Royal Military Academy [19] , but because of Nasser's participation in the protests, he was denied admission. Disappointed, he entered the law college at the University of Cairo [20] , however, having studied for only a semester, dropped out of college and again applied to the academy [21] . Being obsessed with liberating heroes and conquerors, Nasser considered a career in the army the first goal [22] .

Realizing that he needed a patron, in the same year, Nasser secretly met with Deputy Minister of War Ibrahim Khairi Pasha [19] , who promised him support [19] , and at the end of the year he entered the academy [20] [23] , where he met Abdel Hakim Amer and Anwar Sadat , who in the future became his closest associates [19] . Studying hard, Nasser practically broke ties with his family, and in July 1938 he was released as a lieutenant and assigned to the city of Mankabat near Assiut [14] . In the local garrison, Nasser and his close friends, including Amer and Sadat, discussed the widespread corruption in the country and their desire to overthrow the monarchy and stood out as the leader of the group [24] .

In 1941, Nasser was transferred to the city of Khartoum in Sudan, which at that time was part of the state. For a short time he was reappointed to Egypt, then in September 1942 he returned to Sudan. In May 1943, Nasser took the position of instructor at the military academy in Cairo [14] . In February 1942, the British ambassador Miles Lampson unceremoniously demanded that the king, threatened with forcible abdication, dismiss the Prime Minister Sirry Pasha for his sympathy for the Axis countries . Nasser saw the incident as a gross violation of the sovereignty of the country, feeling ashamed of the fact that the armed forces did not respond to what was happening, but wanted a repetition of what happened to end the rule of Great Britain. In the same year, he was enrolled in the General Staff Academy [25] and began to form a group of young officers-convinced nationalists who supported the future revolution [26] . Nasser maintained contact with them mainly through Amer, who continued to search for interested members of the entire officer corps and provided him with a detailed dossier on each of them [27] .

Arab-Israeli War (1947-1949)

Nasser gained his first combat experience in Mandatory Palestine during the Arab-Israeli war of 1947-1949 [28] . First, he wanted to enter the forces of the Supreme Arab Committee under the leadership of Amin al-Husseini , met with him and impressed him [29] , however, for unclear reasons, the authorities refused Nasser [29] [30] .

In May 1948, after the termination of the British mandate, King Farouk sent troops to Palestine [31] , which included Nasser in the 6th Infantry Battalion [32] , who wrote during the war that the Egyptian armed forces were not ready for her, but a soldier thoughtlessly threw at enemy fortifications [31] . He served as deputy commander of the troops in the Fallujah cauldron, on July 12 he was slightly injured. By August, the brigade of Nasser, being cut off from command [33] , was surrounded by Israelis, but, despite the lack of assistance requested from the Jordanian Arab Legion , refused to surrender. After the peace negotiations between Egypt and Israel, the village of Faluja was relegated to the latter [31] .

Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum publicly met with officers, despite the obstacle of the authorities, who were pressured by the British. The noticeable difference in attitude towards veterans between officials and the people only strengthened Nasser's confidence in the need to overthrow the autocracy [34] . He was also bitterly aware that his connection was never rendered assistance [35] . During the fighting in al-Fallujah, Nasser began writing the book “Philosophy of the Revolution” [33] (later he will publish two more: “Memoirs on the Palestinian War” and “On the Road to Freedom” [36] ).

After the war ended, Nasser returned to work as an instructor at the military academy [37] . In October 1948, he attempted to form an alliance with the Muslim Brotherhood, but soon came to the conclusion that their religious ideology was incompatible with his nationalist views, and then tried to limit the influence of this organization through his close associates, but did not leave his own group [31 ] . In February 1949, Nasser joined the armistice delegation on the Greek island of Rhodes , but found the proposed conditions to be humiliating, in particular due to the Israeli occupation of Eilat during negotiations in March of that year [38] .

Revolution

“Free Officers”

Simultaneously with the return of Nasser from the front in Syria, President Husni al-Zaym was overthrown. The success of the coup and its support by the Syrians reinforced Nasser’s revolutionary aspirations. Shortly after arriving at his homeland, he was summoned by Prime Minister Hadi Pasha , who during a conversation tried to find out from Nasser whether he was involved in the creation of a group of dissident officers that he had denied. In the presence of the chief of the general staff, Hadi Pasha hesitated, not daring to begin repressions against the army, and released Nasser. The interrogation forced him to accelerate the preparations for the coup [38] .

After 1949, the group was renamed the " Society of free officers " [37] . Nasser was unanimously elected chairman of its constituent committee, consisting of 14 people of various backgrounds and political views - among the committee members were representatives of the Muslim Brotherhood, the Nationalist Party of the Young Egyptians, the local Communist Party and the aristocracy [38] .

In the parliamentary elections in 1950, mainly due to their boycott by the Muslim Brotherhood, the Wafd party, led by Nahhas Pasha, won the victory, in which the Free Officers saw a threat due to similar views [39] . Accusations of party members of corruption began to be heard, then new rumors and mistrust spread, which helped members of the group climb the political ladder [40] . By that time, their number had grown to 90 people, but there was no close acquaintance and hierarchy subordination between them, but Nasser led them all [40] . He understood that his supporters were not yet ready to speak out against the government, and for almost the next two years he was mainly involved in attracting new members to the group and organizing an underground press [41] .

On October 11, 1951, the government announced the breaking of the Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936, which gave the British the right to own the Suez Canal until 1956. The popularity of this step and the support of the partisan war against the British by the authorities forced Nasser to act [41] , organizing a series of political killings. In January 1952, he, along with associate Hassan Ibrahim, carried out an unsuccessful attempt on the life of the royalist Amer, firing at his car on Cairo Street, as a result of which a passer-by was wounded, which convinced Nasser to abandon such actions in the future [42] .

Amer, close to the king, was appointed by him as chairman of the officer meeting. But Nasser longed for independence of the armed forces from autocracy and, seeing his supporter as a general, wanted him to be ousted by a member of the "Free Officers" by the popular General Naguib , who resigned in 1942 in protest against British arbitrariness and was wounded three times during the war in Palestine . In the elections, Nagub won with a large margin that the nasurists, who had connections with the large newspaper Al-Misri, were used to propagandize army nationalism [43] .

1952 July Coup

On January 25, 1952, 40 policemen were killed in a clash between British forces and the local police in the city of Ismailia , causing a riot in Cairo, killing 76 people. In the light of events, Nasser published a six-point manifest designed to eliminate feudalism and nullify English influence on the country. In May, Nasser learned that the king knew the names of the members of the group and their arrest was inevitable, and the head of the “Free Officers” instructed his ally Dean’s comrade to begin preparations for a military coup [44] .

The group intended not to come to power, but to restore parliamentary democracy. Nasser, a lieutenant colonel by then, did not believe that the Egyptians would follow an officer of such low rank, and submitted to General Naguib, under whose name the coup was carried out. On July 22–23, troops loyal to the “Free Officers” captured government buildings in the capital, including the General Staff building, radio stations, and police stations. Unlike many associates, Nasser did not command a detachment, but, in order to conspire, disguised himself as a civilian, exercised control over what was happening on the ground. To prevent foreign intervention, two days before the coup, the lieutenant colonel warned the British and American governments about it, who agreed to abandon Farouk’s support [44] [45] . Under US pressure, he was sent to the honorary link [46] .

On June 18, 1953, a republic was proclaimed in Egypt, Naguib took over as president [44] . The military intended to engage in the struggle against the aristocracy, and transfer administrative functions to civilians, for which the former prime minister, Ali Mahir, was asked to form a cabinet without members of the armed forces entering it [47] . "Free officers" became part of the Revolutionary Command Council , headed by the president, Nasser was appointed his deputy [48] . Due to too radical, according to Mahir, transformations - agrarian reform, abolition of the monarchy and the reorganization of political parties [49] - which Nasser wanted to implement, relations between the Prime Minister and the Council of the Revolutionary Command were heated, and on September 7, Mahir resigned . He was replaced by Naguib, Nasser took the post of deputy head of the cabinet [50] [51] . In the same month, agrarian reform began, which, in his opinion, gave the Council a distinctive feature and turned the coup into a revolution [52] .

In August 1952, left-wing riots broke out in a textile factory in Kafr al-Davar , during the suppression of which 9 people were killed. In contrast to the majority of members of the SRK, Nasser voted against the execution of two of their instigators. The Muslim Brotherhood supported the Council and, after the coup, demanded four ministerial portfolios in the new government, but Nasser refused the organization, instead offering her two minor posts, provided that the candidates for them were officially non-partisan [52] .

Power

Contradictions with the Bend

In January 1953, overcoming the resistance of Naguib, Nasser succeeded in banning other political parties [53] , except for the Liberation Congress led by him [54] - a poorly organized structure whose main task was to hold mass meetings and lectures in support of the Council [55] . Despite the ban, Nasser remained a supporter of the parliamentary elections, although he did not gain support from the SRK [53] . In March of the same year, he led the delegation at the talks on the withdrawal of British forces from the Suez Canal zone [56] .

When Naguib began to distance himself from land reform and began a rapprochement with the old political forces - the Wafd Party and the Muslim Brotherhood [57] , Nasser decided that the Chairman of the Council should be dismissed. In June, he was appointed Minister of the Interior in exchange for loyal to Naguibu [57], and began to put pressure on the general in order to completely destroy the monarchy [56] .

After February 23, 1954, the SRC gathered without Naguib, on February 25, he resigned. A day later, Nasser, who served as chairman of the council and prime minister [58] , accepted the petition and sent the former president under house arrest. As the general expected, fermentation began in power: calls were heard for the return of Nagib and the dissolution of the SRK [59] . In the hope of reaching a compromise, Nasser visited the General Staff and was initially forced to make concessions [60] , but on February 27, loyal troops surrounded the building [61] . In response, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets the same day, mostly Muslim Brotherhood members calling for the return of the ex-president and the arrest of Nasser. [62]The significant group within the Council, led by Khaled Mohi al-Din, demanded that Naguib be reinstated. Nasser had to concede, but he asked to postpone the return of the general until March 4, which allowed him to approve his supporter Abdel Hakim Amer to the post of commander-in-chief, who had previously been Nagib [63] .

5 марта лояльные Насеру органы госбезопасности провели массовые аресты. С целью подогреть оппозиционные выступления СРК объявил о разрешении старых партий и уходе «Свободных офицеров» из политики [62] , что вызвало широкий народный протест [64] : около миллиона работников транспорта объявили забастовку, тысячи крестьян маршем прошли по Каиру [65] . Стремление Нагиба подавить недовольство силой было саботировано руководством вооружённых сил. 29 марта Насер объявил об отмене недавно изданных указов. В апреле—июне сотни сторонников генерала в армии подверглись репрессиям, Мохи эд-Дин был отправлен представителем Совета в Швейцарию [66] . Король Саудовской Аравии Сауд пытался наладить отношения между Насером и Нагибом, но безуспешно [67] .

Во главе Совета революционного командования

26 октября 1954 года во время речи Насера в Александрии по случаю вывода британских войск из страны, транслировавшейся по радио в арабских странах, в него восемь раз выстрелил член Братьев-мусульман Мухаммед Абдель Латиф, но промахнулся. В толпе началась паника, однако член СРК сумел взять себя в руки и призвал к спокойствию, затем в порыве чувств обратился к народу:

Соотечественники, моя кровь льётся за вас и Египет. Я буду жить ради вас и умру во имя ваших свободы и чести. Пусть они убьют меня; неважно, как долго я давал вам гордость, свободу и честь. Если Гамаль Абдель Насер должен погибнуть, то каждый из вас Гамаль Абдель Насер. … Гамаль Абдель Насер от вас и из вас и клянётся положить жизни ради народа.

— [68]

Неудачную попытку убийства Насер использовал в собственных целях [69] : по возвращении в Каир он приказал начать масштабные чистки, в ходе которых были арестованы тысячи недовольных, в основном принадлежавших к Братьям, 8 членов руководства которых были приговорены к смертной казни, однако лидер движения Сеийд Кутб отделался 15-летним тюремным заключением [70] . Арестам подверглись и коммунисты, 140 верных Нагибу офицеров было разжаловано [69] , сам он был вновь смещён с поста президента и без суда помещён под домашний арест. Устранив политических противников, Насер стал бесспорным руководителем страны [68] .

Несмотря на это, для проведения дальнейших реформ и закрепления в должности Насер недоставало народной поддержки, и в политических целях он отправился в турне по Египту и ввёл цензуру в прессе [71] . На свою сторону Насер привлёк ведущих арабских певцов того времени Умм Кульсум и Абдель Халима Хафеза , в своих песнях прославлявших его арабский национализм, и стал делать на него упор в собственных речах 1954—1955 годов [72] . Ряды сторонников Насера пополнились и драматургами, очернявших его оппонентов. В январе 1955 года он стал председателем СРК до проведения выборов [73] .

В тот же период Насер пытался тайно наладить контакты с Израилем, однако пришёл к выводу, что мир с «экспансионистским государством, презирающим арабов» невозможен [74] . 28 февраля 1955 года израильские войска вторглись ( ) в находившийся под контролем Египта сектор Газа под предлогом прекращения атак палестинских повстанцев. Насер, считая, что египетские вооружённые силы не готовы к конфронтации, не отреагировал подобающим образом, что продемонстрировало неэффективность армии и поставило под угрозу растущую популярность председателя СРК [75] [76] . Впоследствии он отдал приказ о начале блокады израильского судоходства в проливе эт-Тиран и в начале сентября ограничил полёты израильских воздушных судов над заливом Акаба [75] , на что израильтяне ответили ликвидацией 21 сентября демилитаризованной зоны аль-Ауджа на египетской границе [76] .

Одновременно с февральской операцией Израиля между некоторыми региональными союзниками Великобритании был подписан Багдадский пакт , в котором Насер видел угрозу его планам по ограничению английского влияния на Ближнем Востоке и Арабской лиге . Осознавая, что для удержания собственного влияния в регионе Египту необходимы современные вооружения, которые западные страны отказались поставлять на приемлемых финансовых и военных условиях [76] [77] , глава Совета повернулся к государствам Варшавского договора и 27 сентября заключил соглашения с Чехословакией на поставки оружия на 320 миллионов долларов [75] , что позволило более-менее уравнять военную мощь Египта и Израиля и укрепить позицию Насера как противостоящего Западу арабского лидера [76] .

Политика нейтралитета

На Бандунгской конференции , прошедшей в Индонезии в конце апреля 1955 года, Насер был тепло принят как ведущий представитель арабских стран [78] [79] . На пути в Бандунг он посетил Пакистан [80] , Индию [81] , Бирму и Афганистан [82] , а 9 апреля заключил в Каире дружественное соглашение с Индией, укрепившее экономические и политические связи двух стран [83] .

В Индонезии руководитель СРК прилагал силы для объединения прозападных, просоветских и нейтральных режимов в борьбе с колониализмом в Африке и Азии и стремлении к прекращению Холодной войны, что нашло отражение в коммюнике, опубликованном после закрытия конференции [78] , искал поддержки в неприсоединении к оборонным блокам, провозглашении независимости французских колоний Туниса и Алжира, борьбе за право палестинцев на возвращение на родину и выполнение резолюций ООН по арабо-израильскому конфликту . По каждому из этих пунктов участниками саммита была принята резолюция, что одобрили Китай и Индия [84] . Вскоре «позитивный нейтрализм», которого придерживались президент Югославии Иосип Броз Тито и премьер-министр Индии Джавахарлал Неру , был принят концепцией египетской внешней политики и оставался ей в годы Холодной войны [79] [85] . Дипломатические успехи значительно усилили популярность Насера [86] .

Конституция 1956 года и президентство

С существенным укреплением собственных позиций в стране Насер выдвинулся на первый план в Совете революционного командования и заполучил единоличную власть, которая мало кем оспаривалась [82] , особенно в вопросах внешней политики [87] . В январе 1956 года был подготовлен проект новой конституции, предусматривавшей установление однопартийной системы во главе с Национальным союзом [87] , реорганизованным из Освободительного съезда [88] , который, по мнению Насера, так и не смог собрать достаточной народной поддержки [89] . В новую организацию председатель Совета стремился привлечь больше граждан, утверждавшихся в членстве местными партийными комитетами, с целью укрепить массовую поддержку режима [89] . Кандидат на пост президента выдвигался в Национальном союзе [87] .

23 июня того же года в ходе референдума подавляющим числом голосов новая конституция вступила в силу, а Насер был избран президентом [87] . В июле прошли выборы в свежесозданную Национальную ассамблею из 350 депутатов [88] , утверждавшихся главой государства [90] . Новый основной закон провозглашал равноправие полов и запрет дискриминации по половому признаку [91] . В рамах перехода к гражданскому правлению СРК самораспустился, его члены подали в отставку с занимаемых постов [92] . Новый президент стремился потеснить его противников в рядах бывших «Свободных офицеров» и назначил своих ближайших сторонников на значительные должности в правительстве [87] .

Национализация Суэцкого канала

С официальным закреплением Насера как руководителя страны после трёхлетнего переходного периода стремления египетского президента во внутренней и внешней политике столкнулись с региональными интересами Великобритании, недовольной осуждением главой Египта Багдадского пакта, и Франции, не одобрявшей поддержку Насером алжирской войны за независимость . Нейтралитет египетского лидера, признание им коммунистического Китая и оружейная сделка с Чехословакией отдаляли Египет от США. 19 июля 1956 года Соединённые Штаты и Великобритания внезапно отозвали своё предложение профинансировать сооружение Асуанской плотины [92] , ссылаясь на опасения, что осуществление проекта подвергнет экономику государства тяжёлому удару [93] . Насер был глубоко оскорблён этим поступком. Предложение национализировать Суэцкий канал приобрело актуальность с началом вывода британских войск в 1954 году, завершившегося 13 июня 1956 года, и было принято президентом в середине июля после обсуждения с членами бывшего СРК аль-Багдади и инженером Махмудом Юнисом, причём оставшаяся их часть узнала об этом лишь 24 июля, а большая часть министров — лишь за несколько часов до публичного оглашения решения [94] . По иной версии, Насер принял его единолично, ни с кем не советуясь [95] .

26 июля президент Египта в своей речи в Александрии заявил о национализации канала в свете необходимости средств для постройки Асуанской плотины, осудив английский империализм в стране и английский же контроль за доходами от судоходного пути, при строительстве которого, по словам Насера, погибло 120 000 египтян [96] . Таким образом, египетское правительство разорвало соглашение с Великобританией от 19 октября 1954 года [97] , однако всем акционерам были выплачены компенсации [98] .

Речь Насера была крайне одобрительно встречена по всему арабскому миру: тысячи выходили на улицы с лозунгами в поддержку решения [99] , которое обеспечило египетскому лидеру почти полную народную поддержку и прочно закрепило за ним образ «харизматичного лидера» и «защитника Третьего мира » [100] . В день национализации канал был закрыт для израильских судов [98] .

Суэцкий кризис

Франция и Великобритания, будучи основными акционерами канала, увидели в его национализации ещё одну враждебную к ним меру, предпринятую египетским руководством. Насер понимал, что его решение спровоцирует международный кризис и, скорее всего, иностранную интервенцию [101] , однако считал, что у государства есть ещё как минимум два месяца до начала английской военной операции, а израильское вторжение и вовсе расценивал как невозможное [102] . В начале октября Советом Безопасности ООН была принята резолюция по национализации Суэцкого канала, признававшая право Египта на контроль за ним, пока по нему позволено осуществлять иностранное судоходство [103] , после чего Насер счёл, что вторжение маловероятно [104] . Тем не менее, вскоре Великобритания, Франция и Израиль заключили во французском Севре секретное по захвату канала, оккупации его зоны [97] [105] и смещению Насера [106] [107] [108] . 29 октября 1956 года израильские войска вторглись на Синайский полуостров, уничтожив египетские посты на границе, и быстро достигли поставленных задач. Два дня спустя британские и французские самолёты начали бомбардировки египетских аэродромов в зоне канала [109] . Президент страны отдал приказ об отступлении с Синая в целях усиления обороны судоходного пути и предотвращения окружения и уничтожения бронетанкового корпуса на полуострове в случае англо-французской высадки в Порт-Саиде . Амер не согласился с Насером, считая, что египетские танки нужно бросить в бой с израильтянами, но 3 ноября после бурных дебатов уступил [110] . Насер также дал указание блокировать канал путём уничтожения или вывода из строя 49 кораблей на входе в него [109] .

Несмотря на приказ об отступлении, египетские войска в сражениях с израильтянами потеряли около 2 тысяч человек, приблизительно 5 тысяч египтян попали в плен [111] . Амер и призвали Насера заключить перемирие, последний также предложил ему сдаться британской армии. Насер подверг товарищей по бывшему СРК критике, полностью отмёл предложения капитулировать и сам занял пост верховного главнокомандующего [109] . Хоть израильская операция по захвату Синайского полуострова прошла сравнительно легко, престиж египетского лидера на родине и в арабском мире не пострадал [112] . В целях противодействия израильтянам он дал указание раздать около 400 тысяч винтовок добровольцам, из которых были сформированы сотни отрядов, во главе многих из которых стояли политические противники Насера [113] .

Сопротивление вражеской высадке в Порт-Саиде Насер рассматривал как важнейшее стратегическое преимущество в моральном плане. В город в качестве подкреплений были посланы 3-й пехотный батальон и сотни ополченцев, двум пехотным ротам была дана задача организовать народное сопротивление. Президент и аль-Багдади для поднятия боевого духа посетили зону канала. Согласно мемуарам последнего, по пути туда, увидев разбитую египетскую технику, Насер признал, что армия разбита [114] . 5—6 ноября в ходе десанта англо-французские войска столкнулись с жёстким сопротивлением ополчения, что вылилось в уличные бои [113] . Командующий местными войсками был готов начать переговоры о прекращении огня, но по приказу Насера продолжил сражаться. К 7 ноября войска противника заняли большую часть Порт-Саида [115] , защищая который, погибли 750—1000 египтян [111] .

США и СССР осудили вторжение, поддержав резолюции ООН, призывавшие к выводу иностранных войск с территории Египта, при этом администрация президента Дуайта Эйзенхауэра , в отличие от советского правительства, поддержала предложение о размещении на Синае [116] . Это с удовлетворением было воспринято Каиром [117] . К концу декабря английские и французские силы покинули страну [118] , в марте 1957 за ними последовал Израиль, освободивший всех военнопленных [111] [119] . В результате Суэцкого кризиса египетскими властями были ужесточены условия проживания иностранцев и получения гражданства, стало применяться выдворение, которому подверглись в основном граждане Соединённого Королевства и Франции, евреи-иностранцы и некоторые местные евреи [120] .

После окончания боевых действий Амер обвинил Насера в развязывании ненужной войны и в перекладывании ответственности за поражение на вооружённые силы [121] . 8 апреля 1960 года канал был вновь открыт [122] . Широко расцениваемый [ what? ] провал интервенции и одной из её целей — смещения президента — значительно увеличил его популярность [97] .

Панарабизм и социализм

К 1957 году панарабизм стал главенствующей идеологией в арабском мире, а Насер воспринимался большинством арабов как неоспоримый лидер [123] . Каирская радиостанция « Голос арабов » широко распространяла его панарабские воззрения и сыграла значительную роль в росте его популярности в арабских странах [124] . С помощью посольства Египта сторонниками президента этой страны для пропаганды его идей были приобретены СМИ в Ливане, региональном пресс-центре. Насера также поддерживали различные националистические организации, именовавшие себя «насеритами», хотя сам он предпочитал называть их «арабскими националистами». Несмотря на многочисленность и хорошее финансирование, они были плохо организованы и не имели постоянных структур [125] .

В январе 1957 года США приняли доктрину Эйзенхауэра , предполагавшую противостояние распространению коммунизма и его предполагаемым агентам на Ближнем Востоке. Хоть Насер и противился коммунизму в регионе, распространение его панарабистских взглядов расценивалось как угроза местными прозападными режимами. Эйзенхауэр пытался изолировать египетского лидера и ослабить его влияние на Ближнем Востоке путём усиления короля Саудовской Аравии Сауда [126] [127] . В этом же месяце новоизбранный премьер-министр Иордании, сторонник Насера [128] Сулейман ан-Набульси заключил между Иорданией, Египтом, Сирией и Саудовской Аравией военный договор [129] .

Отношения между Насером и иорданским королём Хусейном заметно ухудшились после того, как последний обвинил первого в организации двух попыток его смещения, хоть причастность египетского руководителя так и не была доказана [130] [131] , и отправил правительство ан-Набульси в отставку [129] [132] . «Голос арабов» назвал Хусейна «инструментом империалистов» [133] . Отношения с Саудом также приобрели характер противостояния после того, как тот стал считать рост популярности Насера в королевстве опасной угрозой монаршему дому [129] . Несмотря на негативное отношение руководства Иордании, Саудовской Аравии, Ирака и Ливана, он продолжал пользоваться расположением жителей этих и других арабских стран [125] .

К концу 1957 года Насер завершил национализацию оставшихся в стране британских и французских активов, в том числе предприятий табачной, цементной, фармацевтической и фосфатной промышленностей. Усилия по снижению налогов и привлечению иностранных инвесторов не принесли заметных результатов, и национализации подверглись ещё больше компаний, которые были объединены с целью поспособствовать экономическому развитию, но вскоре она была прекращена: в частных руках оставалось около двух третей фирм. Предпринятые руководством Египта меры имели некоторый успех: увеличились производство сельскохозяйственной продукции и инвестиции в индустриализацию. Президент выступил инициатором постройки металлургического завода в Хелуане , вскоре ставшего крупнейшим предприятием в стране, обеспечив её продуктом и тысячами рабочих мест. Насеру также принадлежала идея обратиться к Советскому Союзу за помощью в сооружении Асуанской дамбы [134] .

Объединённая Арабская Республика

Несмотря на популярность египетского лидера в арабском мире, к середине 1957 года единственным региональным союзником Насера была Сирия. В сентябре турецкие войска были сосредоточены возле сирийской границы, что дало пищу слухам о том, что страны Багдадского пакта могут вторгнуться в это государство с целью свержения его левого правительства. Насер приказал отправить в Сирию армейский контингент в качестве символа солидарности, что ещё больше подняло его престиж в арабских странах и в Сирии в частности [135] .

С ростом политической нестабильности в Сирии в Египет стали отправляться сирийские делегации с требованием о немедленном объединении двух государств, на что Насер не соглашался, ссылаясь на несовместимость их политической и экономической систем, недостаток близости, опыт вмешательства сирийских вооружённых сил в политику и их глубокое деление на фракции [136] . Тем не менее, в январе 1958 года второе сирийское посольство сумело убедить Насера в угрозах прихода к власти в Сирии коммунистов и скатывании её в междоусобицу [137] , и тот согласился на союз, но на условиях полного политического объединения во главе с ним как президентом ОАР, на что сирийские делегаты во главе с президентом Шукри аль-Куатли дали своё согласие [138] . 1 февраля новое государство было провозглашено, что встретило массовое одобрение в арабском мире [139] . Насер развернул преследование местных коммунистов, уволив многих с государственных должностей [140] [141] .

24 февраля во время нежданного визита Насера в Сирию его приветствовали сотни тысяч людей [142] . В Дамаск прибыл и наследный принц Северного Йемена Мухаммед аль-Бадр с целью переговоров о вступлении в ОАР. Вместо полного слияния Насер согласился сформировать непрочные Объединённые Арабские Государства [143] . Тем временем король Саудовской Аравии планировал убить Насера во время обратного полёта в Каир [144] . 4 марта на митинге в сирийской столице президент нового образования продемонстрировал саудовский чек на имя начальника сирийской разведки Сараджа , ярого сторонника Насера [145] . В результате провала заговора старшие члены монаршего дома вынудили Сауда передать большую часть полномочий своему брату Фейсалу , противнику Насера, придерживавшемуся идеологии панисламизма [146] .

5 марта президент ОАР объявил о принятии временной конституции, предполагавшей создание Национальной ассамблеи из 600 депутатов (400 от Египта и 200 от Сирии) и роспуск всех политических партий. Вице-президентами от Египта были назначены аль-Багдади и Амер, от Сирии — аль-Асали и Акрам аль-Хаурани [146] . Вскоре Насер посетил Москву, где встретился с Хрущёвым , призвавшим разрешить коммунистическую партию, на что первый ответил, что это внутреннее дело государства. Ошеломлённый, его собеседник стал отрицать намерения вмешаться во внутреннюю политику ОАР. Разногласие было забыто в стремлении обоих лидеров предотвратить распад сирийско-египетского союза [147] .

Влияние на арабский мир

В Ливане столкновения между насеритами и сторонниками президента Шамуна , стойкого противника египетского лидера, к маю 1958 года вылились в политический кризис . Насер стремился к вхождению Ливана в состав ОАР, чему противился приверженец дальнейшей независимости Шамун [148] , и поручил Сараджу надзор за ситуацией: тот ограниченно помог ливанским насеритам деньгами, лёгкими вооружениями и обучением офицеров [149] . Насер не жаждал контроля над Ливаном, видя в нём особый случай, но добился того, что Шамун не стал баллотироваться на второй срок [150] .

14 июля того же года иракские офицеры Абдель Керим Касем и Абдул Салам Ареф свергли монархию, на следующий день бывший премьер-министр Нури ас-Саид , ведущий противник Насера в арабских странах, был убит [151] . Глава объединённого государства признал новое иракское руководство, заявив, что «любая атака на Ирак будет равнозначна атаке на ОАР». 15 июля по официальным просьбам Ливана и Иордании с целью предотвратить приход насеритов к власти в первом высадились военнослужащие Корпуса морской пехоты США, во второй — британские спецподразделения. Президент Египта считал, что революция 14 июля открыла дорогу для арабского объединения [152] . 19 июля он впервые открыто признал, что борется за союз всех арабских стран, хотя планов по присоединению Ирака к ОАР у Насера не было [153] . Большинство членов Совета революционного командования Ирака были согласны на объединение с Егпитом и Сирией [154] , но Касем желал независимости страны и был недоволен широкой поддержкой Насера в народе [151] .

Осенью 1958 года он создал комитет по развитию Сирии из трёх членов, куда вошли Закария Мохи эд-Дин, аль-Хаурани и Салах ад-Дин Битар . Двух последних, которые были баасистами и имели собственные взгляды на управление страной, Насер устранил с политической арены, переведя на эту работу в Каир. Власть над Сирией оказалась в руках Сараджа, который превратил её в полицейское государство, арестовывая и высылая недовольных проведением египетской земельной реформы землевладельцев и коммунистов [155] . После того, как в сентябре того же года президентом Ливана был избран Фуад Шехаб , отношения между этим государством и ОАР значительно улучшились. 25 марта 1959 года Насер и Шехаб встретились на сирийско-ливанской границе для переговоров о завершении ливанского кризиса [156] .

Отношения между Насером и Касемом ожесточились [157] после подавления 9 марта 1959 года верными иракскому лидеру силами восстания в Мосуле , поднятого за день до этого сторонниками присоединения к ОАР при поддержке её руководства [158] . Лидер объединённого государства подумывал об интервенции с целью оказания помощи бунтовщикам, но не сделал этого [159] . Так как иракские коммунисты поддерживали Касема, их египетские единомышленники подверглись преследованию со стороны властей. Несколько влиятельных коммунистов, в том числе Халед Мохи эд-Дин, вернувшийся в Египет в 1956 году, были арестованы [157] .

К декабрю того же года политическая ситуация в Сирии начала терять стабильность, и Насер передал руководство провинцией Амеру. В знак протеста против назначения многие местные функционеры подали в отставку. Когда обстановка накалилась, Насер встретился с лидерами сирийской оппозиции и заявил, что власть в ОАР принадлежит ему как «избранному» президенту, а те, кому это не нравится, могут «уйти» [155] .

Распад ОАР

Противники союза заняли прочные позиции среди экономической, политической и военной элит Сирии [160] . В ответ на ухудшение состояния её экономики, которое Насер связывал с её «буржуазностью», в июле 1961 года президент ОАР начал социалистические преобразования и национализировал обширные секторы местной экономики [161] . Для того, чтобы сдержать нараставший политический кризис, в сентябре этого же года Сарадж был отправлен в отставку. В Египте экономическая ситуация была лучше: ВНП вырос на 4,5 процента, наблюдался быстрый рост промышленности [162] . В 1960 году египетская пресса, и ранее сотрудничавшая с властями, подверглась национализации с целью усиления пропаганды социалистических реформ [71] .

28 сентября 1961 года сторонники выхода из состава ОАР в рядах сирийских вооружённых сил осуществили государственный переворот [163] . В ответ верные союзу войска подняли восстание на севере страны, в её крупных городах прошли митинги в поддержку Насера [160] . Для поддержки своих сторонников он направил в Латакию египетские спецподразделения, но через 2 дня отозвал их, ссылаясь на недопустимость арабской междоусобицы. В речи от 5 октября [164] Насер признал личную ответственность за распад объединённого государства и новое сирийское правительство [165] . Неофициально он обвинил в произошедшем вмешательство его противников в арабском мире. Случившееся тяжело повлияло на египетского президента [164] .

Рост регионального влияния

Позиции Насера в регионе значительно изменились после того, как сторонник лидера Египта Абдалла ас-Саляль 27 сентября 1962 года сверг в ходе военного переворота короля Северного Йемена Мухаммеда аль-Бадра [166] . Бывшему монарху и его приверженцам начала оказывать поддержку Саудовская Аравия, и 30 сентября ас-Саляль обратился к Насеру за военной помощью. Египет оказался прочно втянут в продолжительную гражданскую войну, пока его войска не покинули страну в 1967 году [167] . Большинство старых соратников Насера задавалось вопросом о необходимости продолжения египетского участия, но Амер заверил его в скорой победе [168] . В 1968 году президент признал, что решение о вторжении в Йемен было «просчётом» [167] .

В июле 1962 года Алжир провозгласил независимость от Франции, завершив войну с ней . Будучи последовательным сторонником алжирского движения за независимость и поддерживая его финансово и политически, Насер видел в её провозглашении свою личную победу [168] . В начале 1963 года группа его сторонников в саудовской королевской семье во главе с принцем Талялем (известная как ), вместе с начальником генерального штаба вооружённых сил Иордании сбежали в Египет [169] .

8 февраля 1963 года объединившиеся баасисты и насериты свергли Касема, который был вскоре застрелен. Пост президента занял сторонник Насера Абдул Салам Ареф [168] . 8 марта их единомышленники осуществили военный переворот в Сирии [170] . 14 марта новые иракское и сирийское правительства направили в Каир делегации на переговоры о формировании арабского союза [171] . На встрече Насер раскритиковал сирийских баасистов за «помощь» в развале ОАР [172] и заявил о своём лидерстве среди арабов. Переходное соглашение об объединении, предусматривающее создание федеративного государства [171] , было подписано 17 апреля и вступало в силу в мае 1965 года [173] , однако несколько недель спустя после чисток в сирийском офицерском корпусе, которым подверглись сторонники Насера, договор был расторгнут. 18 июля во главе с полковником они попытались устроить военный переворот , но потерпели неудачу, после чего Насер назвал баасистов «фашистами» [174] .

В январе 1964 года на саммите Лиги арабских государств в Каире Насер призвал арабов объединиться против отвода Израилем вод реки Иордан в экономических целях. Действия израильтян были восприняты Сирией и Иорданией как объявление войны [175] . В этой, по его словам, «катастрофической ситуации» он винил межарабские разногласия. Он отговорил сирийских и палестинских боевиков от провокаций в сторону Израиля, заявив, что не планирует воевать с ним. За время съезда Насер наладил близкие связи с королём Иордании Хусейном и завязал отношения с руководителями Саудовской Аравии, Марокко и Сирии. В мае президент Египта инициировал создание Организации освобождения Палестины , таким способом формально разделив с ней своё лидерство по палестинскому вопросу [176] , а на деле использовав для контроля борцов за освобождение Палестины [177] . Главой ООП стал протеже Насера [176] .

После многих лет координации внешней политики и налаживания связей в 1961 году президенты Индонезии Сукарно и Югославии Иосип Броз Тито и премьер-министр Индии Джавахарлал Неру сформировали Движение неприсоединения [178] , провозгласившее собственными целями противостояние войне и колонизации и поощрение экономического развития развивающихся стран [179] . В 1964 году Насер занял пост президента организации и провёл её второй съезд в Каире [180] .

В конце 1950-х — начале 1960-х Насер играл значительную роль в укреплении африканского единства, хотя его влияние на континент с 1962 года значительно сместилось в сторону Алжира. В этот период Египет служил пристанищем для антиколониальных лидеров из некоторых стран Африки, а Каир — площадкой для распространения их взглядов. Мнение президента страны стало решающим в дискуссиях среди африканских лидеров, приведших к созданию Организации африканского единства в 1961 году [181] .

Модернизация и внутренние конфликты

Университет аль-Азхар

В 1961 году Насер, желая окончательно утвердить Египет лидером арабского мира, начал продвигать «вторую революцию», призванную объединить исламское и социалистическое учения. С этой целью и в стремлении упрочить влияние наиболее авторитетного суннитского университета аль-Азхар по сравнению с Братьями-мусульманами и поддерживавшимся Саудовской Аравией более консервативным ваххабизмом руководитель государства начал реформировать это учебное заведение [182] . С 1953 года он использовал наиболее лояльных властям университетских улемов , чтобы уравновесить Братьев [53] . По указанию Насера в учебный план были внесены изменения, что повлекло за собой преобразования в школах: были созданы учебные заведения совместного обучения, в школьный курс была включена эволюция. Реформы также предусматривали слияние религиозных и светских судов. Под давлением египетского лидера университет издал фетву , признававшую принадлежность шиитов, алавитов и друзов к основному направлению ислама, хотя на протяжении веков называл их еретиками [182] .

Соперничество с Амером

После распада ОАР Насер стал беспокоиться о неспособности Амера тренировать и модернизировать армию и о том, что он выстроил государство в государстве в вооружённых силах и разведке [183] [184] . В конце 1961 года был создан Президентский совет, утверждавший назначения на высшие армейские посты, что ранее в одиночку делал Амер. По указанию главы государства они стали производиться не из личной преданности, а по заслугам [185] . Сторонники Амера в офицерском корпусе воспротивились этим мерам, и под их давлением Насер был вынужден отменить их. В начале 1962 года он снова попытался лишить Амера контроля над командованием вооружёнными силами [186] , на что тот впервые ответил открытой критикой президента Египта и тайно начал сплачивать лояльных себе офицеров [185] . Опасаясь вооружённой конфронтации между военными и гражданским руководством, Насер пошёл навстречу сопернику [187] .

Национальная хартия и второй президентский срок

В октябре 1961 года Насер начал реализовывать широкую программу национализации, веря, что полный переход к социализму поможет решить проблемы страны и что он мог бы предотвратить развал ОАР [188] . С целью упрочить свою поддержку в народе в противовес влиянию вооружённых сил в 1962 году он представил Национальную хартию, призывавшую к созданию всеобщей системы здравоохранения, строительству доступного жилья, появлению профучилищ, увеличению прав женщин, семейному планированию и расширению Суэцкого канала, год спустя была принята новая конституция [183] .

Лидер Египта пытался также контролировать госаппарат и предотвратить его разрастание [183] . Новое законодательство предусматривало минимальный размер заработной платы, начисление доли прибыли работникам, бесплатные образование и медицину, уменьшение рабочего времени и поощряло трудящихся к участию в управлении. Земельные реформы гарантировали защиту прав фермеров-арендаторов [189] , способствовали росту сельского хозяйства и позволили сократить число голодающих в сельской местности [190] . В результате национализации доля государства в египетском бизнесе возросла до 51 процента. Национальный союз был переименован в Арабский социалистический союз [191] . Одновременно власти страны развернули репрессии: тысячи исламистов и множество офицеров были арестованы [188] . В знак протеста против движения Египта к советской системе управления соратники Насера аль-Багдади и Хусейн аш-Шафеи подали в отставку с занимаемых постов [166] .

В 1965 году Насер на безальтернативных выборах в форме референдума был переизбран президентом. Его политическим оппонентам было законодательно запрещено баллотироваться, а ближайшие сторонники египетского руководителя потеряли политические привилегии. Год спустя главный идеолог Братьев-мусульман Сайид Кутб был заключён в тюрьму и по обвинению в попытке убийства Насера приговорён к смертной казни [192] . В том же 1966 году экономический рост начал замедляться, государственный долг значительно увеличился, и Насер ослабил контроль над частным сектором, поощряя госзаймы и стимулируя экспорт [193] . В конце концов экономика страны приблизилась к краху, что значительно уменьшило популярность Насера [194] .

Присвоение звания Героя Советского Союза

Во время официального визита Н. С. Хрущёва в Египет с 9 по 25 мая 1964 года по его личной инициативе 13 мая того же года указом Президиума Верховного Совета СССР Насер [195] и Амер [196] были удостоены звания Героев Советского Союза [197] , что было негативно воспринято советским обществом [198] [199] : высказывалось недовольство тем, что члены египетской компартии подвергались преследованиям, а Хрущёв не внял возражениям других членов руководства СССР по поводу награждения. Этот инцидент стал одним из предлогов для обвинения Первого секретаря ЦК КПСС в «субъективизме» и «волюнтаризме» во время его отстранения в октябре 1964 года [197] [200] [201] .

Награждение породило ряд анекдотов и куплетов [202] [203] , в частности:

Original text (rus.)Lives in the sand and eats from the belly

Half-fascist, half-wrestler,

Hero of the Soviet Union,

Gamal Abdel-on-all-Nasser .- [195]

Original text (rus.)He (Khrushchev) awarded Nasser the Order of Lenin and the golden star of the Hero of the Soviet Union for the destruction of the Egyptian Communist Party, but did not give him the Order of Victory for the defeat in the Six-Day War.Original Text (Eng.)He managed to award Nasser an Order of Lenin and the gold star Hero of the Soviet Union for destroying the Egyptian Communist Party, but he did not give an Order of Victory for the defeat in the Six-Day War.- [204]

It is reflected in the work of Vladimir Vysotsky :

Original text (rus.)Losing True Faith -

It hurts me for our USSR:

Take the order from Nacer -

Not suitable for the Order of Nasser!

You can even cover the floor with a mat,

Give gifts at random

Calling Nasser our brother

But giving a Hero is throwing!

Why is there no gold in the country?

They gave away, bastards, gave away.

It would be better to give the war

And Nasser after forgive us!- [202] [205]

and Alexander Galich :

Original text (rus.)So what are you doing,

Handsome, fascist upbringing,

Crowned by our order

And the Golden Star ?!- [202] [205]

The Six Day War

In May 1967, the Soviet Union warned Nasser of Israel’s forthcoming military operation against Syria, but the chief of the Egyptian general staff, Mohammed Fawzi , sent by Nasser to Syria, noted the lack of concentration of Israeli troops on the border and found the Soviet warning unreasonable [206] [207] . Amer used Soviet information as an excuse to send troops to Sinai on May 14, after which the head of Egypt demanded the withdrawal of UN forces from the peninsula [206] [208] . Earlier that day, he received a message from Jordanian King Hussein , which spoke of a conspiracy between Israel and the United States to draw Egypt into the war. Amer hid from the President of Egypt that the letter was received on May 2, and transmitted it only on May 14 [209] [210] . Despite the fact that in the previous months, Hussein and Nasser accused each other of trying to avoid a war with Israel, the king suspected that the Egyptian-Israeli war could lead to the latter’s occupation of the western bank of the Jordan River [209] . The United States and the USSR assured the President of Egypt that the United States would deter Israel from attack, and he, in turn, announced that his country would only defend itself [211] .

On May 21, Amer asked the Egyptian president to order the blockade of the Et-Tiran Strait, and assured Nasser that the armed forces were ready for conflict [212] , of which Nasser doubted [213] . He believed that the blockade would be a formal reason for Israel to start a war [209] . Amer advocated a preemptive strike [214] , which Nasser did not go to [215] because of the belief that the Air Force lacked pilots and that the officers selected by the field marshal were incompetent [216] . The head of the country also believed that in the event of an Israeli attack due to the numerical superiority of the Egyptian troops, they will be able to restrain the enemy for at least two weeks, which will allow the start of peace negotiations [217] . By the end of May, Nasser, under the pressure of the Arab public and the governments of various countries of the Arab world [207] [218], stopped resisting the war and resigned to its inevitability [217] [219] . On May 26, he announced that the main task of the Arabs would be the destruction of Israel [220] . On May 30, Jordan became part of the Joint Arab Command, where Egypt and Syria were already composed [221] .

On the morning of June 5, Israeli planes attacked the Egyptian Air Force airfields and destroyed most of them, Israeli armored units broke through the Egyptian defense lines and captured the city of El Arish [222] . The next day, Amer ordered the withdrawal of troops from the Sinai Peninsula, which caused the greatest loss to the Egyptians during the entire conflict [223] . Soon, the Israelis occupied the peninsula, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, captured in 1948 by Egypt and Jordan, and the Syrian Golan Heights [222] . After the Egyptian garrison in Sharm el-Sheikh was cut off by the enemy, Nasser arrived at the Ministry of Defense in order to familiarize himself with the situation on the fronts and met with Amer, with whom he entered into a skirmish [224] . The Supreme Executive Committee, formed by Nasser to control the activities of the armed forces, concluded that the confrontation between the field marshal and the president and the complete incompetence of the first led the country to a series of military defeats [222] . In his memoirs, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Egypt in 1973-1977, Ismail Fahmi wrote that the constant failures of Egypt on the battlefield were caused by the fact that Nasser dismissed any rational analysis of what was happening and made a series of unreasonable decisions [225] .

Resignation and its consequences

I made a decision with which I need your help. I decided to completely abandon for the good of any official position and political role and return to the ranks of the masses, doing my duty among them, like any other citizen. Time to act, not grieve. ... All my heart is with you, and may your hearts be with me. May God be with us - faith, hope and the right path in our hearts.

- from a speech by Nasser on June 9 [226]

During the first 4 days of the war, the Arab world believed in propaganda predicting an inevitable Arab victory, but on June 9, the president in his televised speech told the Egyptians about the defeat [226] . Later that day, he announced his resignation and the transfer of all powers to Vice-President Zakaria Mohi al-Din, who was not aware of the plans of the president and resigned from his post [227] . Hundreds of thousands of sympathizers took to the streets of Egypt and Arab countries in protest of the decision [228] , chanting: “We are your soldiers, Gamal!” [229] . On June 10, he returned to the presidency [229] .

On July 11, Amer was replaced by General Fawzi as commander in chief [230] [231] , to which field marshal supporters responded with protests, 600 of them went to the Ministry of Defense and demanded Amer’s reinstatement. After a third of his supporters were fired from the army [232] , he planned a military coup on August 27. Nasser was aware of the conspiracy, and he demanded a personal meeting from Amer, at which he informed Field Marshal about the failure of the coup on August 24. He denied everything, but was placed under arrest and committed suicide on September 14. Despite the conflict between them, Nasser declared the death of Amer as the loss of a "closest friend" [233] . Soon, the Egyptian leader began the process of de-politicization of power structures by mass arrests of field marshal supporters in their ranks [234] .

On August 29, at the OAS summit in Sudan’s Khartoum, Nasser lost his leadership to King Faisal of Saudi Arabia. A ceasefire was concluded at the congress, ending the civil war in Yemen, and resolution [235] was adopted. The USSR soon replenished Egyptian arsenals half of their former state and severed diplomatic relations with Israel. In an effort to warm up the confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States, Nasser during the war broke off relations with the latter [236] . In November, Egypt adopted UNSC resolution 242 , calling for the withdrawal of Israeli troops from territories occupied during hostilities. According to one version, this diplomatic step allowed Nasser to extend the time necessary to start a new conflict with Israel; otherwise, it meant the fading of his interest in the declaration of independence of Palestine [237] .

Recent years in power

Domestic Reforms

On June 19, 1967, Nasser was appointed Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief [238] . After the military tribunal condescendingly treated Air Force officers accused of negligence during the war, student and labor protests began in late February 1968, calling for large-scale political reforms [239] [240] . In response, the Egyptian leader removed most of the military from the government and replaced several senior members of the Arab Socialist Union with eight civilian posts in their posts [241] . By March 3, Egyptian intelligence had eased pressure on citizens, focusing on foreign operations, and the president announced the "end of the state of muhabarat " [242] .

On March 30, Nasser presented a manifesto proclaiming the restoration of civil liberties, greater independence of the parliament from the executive branch [240] , significant structural changes within the ASS and an anti-corruption campaign in the state apparatus [241] . In May, the proposed measures were approved by referendum, and elections were held in the supreme body of the ACC - the Supreme Executive Committee [240] . Despite the fact that most of the promises did not materialize, the manifesto was an important step on the path to liberalization [241] .

In December 1969, Sadat and Hussein al-Shafei were appointed by Nasser as vice presidents. By then, his relationship with old associates, namely Khaled and Zakaria Mohi ed-Dynami and the former vice president of Sabri , had become tense [243] . By mid-1970, after reconciliation with al-Baghdadi, Nasser was thinking about replacing Sadat with the first [244] .

War of Attrition

In February 1968, the President of Egypt launched the War of Attrition with Israel in order to recapture the lands he had seized, ordering an artillery shelling of Israeli positions east of the blocked Suez Canal [245] . After the Battle of Karama in March, Nasser offered arms and finance assistance to the Fatah movement, led by Yasser Arafat , advising Arafat to consider reconciliation with Israel and the creation of a Palestinian state in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank [246] , thus effectively losing the Fatah leader its leadership on the Palestinian question [237] .

The Israelis responded to the Egyptian shelling with shelling and bombing of enemy territory and attacks by sabotage troops, which led to the flight of residents of Egyptian settlements along the western bank of the canal [247] [248] . Nasser stopped all military operations and, with financial assistance from various Arab states, began the construction of fortifications. In March 1969, the war resumed [249] . In November of the same year, Nasser mediated an between the PLO and the Lebanese Armed Forces, which gave the Palestinian insurgents the right to use Lebanese territory to attack Israel [250] .

In June 1970, the President of Egypt, under pressure from the Soviet Union, fearing the development of a regional conflict in the war with the United States [251] [252] , supported the proposed by US Secretary of State William Rogers , envisaging the cessation of hostilities and the withdrawal of Israeli troops from Egyptian territory, but the plan was rejected by Israel, the PLO, and most countries in the Arab world, with the exception of Jordan [244] . Nasser believed that the ceasefire would serve as a tactical step towards the conquest of the Suez Canal [253] . He anticipated any desire to begin direct negotiations with Israel, believing that their conduct would be tantamount to surrender [254] . In the end, Israel agreed to a ceasefire, which Nasser used to place ground-to-air missiles in the channel channel [251] [252] .

Meanwhile, the conflict between the increasingly autonomous PLO and the country's authorities escalated in Jordan [255] : after hijacking aircraft at the Dosons Field, the Jordanian army launched an operation to expel Palestinian militants. The fighting increased the likelihood of war in the region and prompted Nasser to convene an emergency congress of the Organization of Arab States [256] in Cairo on September 27, where the Egyptian president held peace talks [257] .

Death and Funeral

On September 28, after the summit and seeing off the last emir of Kuwait Sabah III, the head of Egypt suffered a heart attack and was transported to his home, where, despite the medical assistance provided, he died several hours later [258] . Atherosclerosis , varicose veins and diabetes complications, which Nasser had been suffering from since the beginning of the 1960s, were named as the cause of death. He was a heavy smoker, and his two brothers died of heart disease before they reached 60, and also suffered from high blood pressure. The state of health of the president before his death was not known to the people [259] [260] . In 1966 and in September 1969 he already suffered heart attacks, after the second attack Nasser spent 6 weeks in bed [259] .

Nasser's death shocked Egypt and the Arab world. [261] The funeral on October 1 brought together at least 5 million people [262] [263] . The 10-kilometer procession stretched from the old headquarters of the Council of the Revolutionary Command and moved with the MiG-21 flying over it. The flag-wrapped coffin was placed on the front of the gun , in which 6 horses were harnessed, and a cavalry convoy was ahead [263] . The ceremony was attended by the leaders of all Arab countries, except for the Saudi King Faisal [264] . King of Jordan Hussein and Arafat cried, Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi fainted twice from stress twice. Several representatives of the non-Arab world, including Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR A.N. Kosygin and French Prime Minister Jacques Chaban-Delmas , also accompanied Nasser on his last journey [262] .

Almost immediately after the start of the procession, people surrounded the coffin, shouting: "There is no god but Allah, and Nasser is the beloved of God ... Each of us is Nasser." The police unsuccessfully tried to calm the crowd, as a result of which the majority of representatives of foreign states were withdrawn from it. The final destination was the Nasr Mosque, renamed the Abdel Nasser Mosque, where he was buried [263] .

Thousands of people took to the streets of major cities in the Arab world as a sign of grief: more than 12 people died in the riots in Beirut, in Jerusalem, about 75,000 Arabs marched through the old city with the slogan “Nasser will never die.” The Lebanese newspaper came out with the headline "One Hundred Million People - Arabs - Orphans" [263] .

Heritage

Nasser completely freed Egypt from British influence [265] , during his reign the country became an influential force among developing states [266] . One of the main tasks of his domestic policy was to ensure social justice, which he regarded as a prerequisite for liberal democracy [267] . While Nasser was in power, Egyptians were provided with housing, education, work, health care, benefits and other support measures in volumes unprecedented for Egypt, feudal influence on the country was weakened [266] [268] . By the end of his presidency, employment levels and working conditions improved significantly, but poverty was still high, and significant resources earmarked for social security went to military needs [267] .

Thanks to agrarian reform, large-scale modernization projects, including the construction of the steel center of Helwan and Aswan Dam, as well as nationalization, the state economy has grown significantly. After economic growth in the early 1960s, it began to experience a recession that lasted until the end of the decade, and only recovered in 1970 [269] . The culture of Egypt under Nasser’s rule was undergoing a “golden age”, dominating the Arab world [270] .

During the presidency of Hosni Mubarak , Nasristist parties began to emerge in the country, the first of which was the [271] [272] , which acquired great influence [273] . The internal party splits that began in 1995 led to the creation of small parties [274] , one of which was Al-Karama, founded by Hamdin al-Sabahi in 1997. Al-Sabahi took third place in the 2012 presidential election [275] . Followers of Nasser were among the founders , one of the main opposition forces to Mubarak [276] . On September 19, 2012, 4 Naserit parties, including ADNP and al-Karama, formed the United Nasserist Party [277] .

Image

Президент Египта был известен своими тесными отношениями с народом [278] [279] : несмотря на покушения, Насер был доступен для простых людей [280] . Умелый оратор [281] , в 1953—1970 годах Насер произнёс 1359 речей — рекорд для руководителей Египта [282] . Несмотря на то, что местные интеллектуалы активно критиковали его во время Шестидневной войны и после его смерти, народ симпатизировал ему при жизни и после кончины [278] . Ситуация в стране во время правления Мубарака подогрела ностальгию по Насеру, президентство которого связывалось с идеей национального предназначения, надеждой, социальной сплочённостью и культурной мощью [270] .

В настоящее время Насер остаётся иконой в арабском мире [266] [283] как символ его единения и достоинства [284] [285] [286] и видная фигура в современной ближневосточной истории [23] . Во время Арабской весны , вылившейся в 2011 году в революцию в Египте , фотографии Насера демонстрировались на акциях протеста [287] [288] .

Criticism

Критики Насера расценивают его как диктатора, подавлявшего движение к демократии, заключившего в тюрьму тысячи диссидентов и создавшего репрессивный режим, ответственный за многочисленные нарушения прав человека [268] . Египетские исламисты, особенно члены преследовавшихся Братьев-мусульман, видели в Насере деспота и тирана [289] . Некоторые местные либеральные и исламистские критики, включая основателей Новой партии Вафд , осуждали его популярность в массах как продукт манипуляции и демагогии [290] .

Американский политолог Марк Купер писал, что наследие Насера было «гарантией нестабильности» из-за его опоры на личную власть и отсутствия в его правление сильных политических институтов [291] . Историк Абд аль-Азим Рамадан считал его нерациональным и безответственным лидером, чья склонность к единоличному принятию решений привела, среди прочего, к египетским потерям в ходе Суэцкого кризиса [292] . Закария Мохи эд-Дин обвинял Насера в пустом блефе в преддверии Шестидневной войны, а его действия во время её связывал с диабетом [293] .

В своей инаугурационной речи 7 октября 1970 года преемник Насера Садат заявил о намерении «продолжать путь Насера», но с укреплением собственных позиций внутри страны после Войны Судного дня начал отходить от политики предшественника [273] [294] . Новый президент предпринял меры по открытию экономики государства для зарубежных инвесторов [295] .

В конце 1940-х годов в Египет начали прибывать военные советники из числа бывших нацистов [296] . Иммиграция, которую, как считается, приветствовал Насер, продолжилась и в 1950-х годах [297] . Общее число немцев, нашедших убежище в стране, составило не менее 150 человек, которые в тот период открыто жили в Каире. Среди них был и разыскивавшийся Центром Симона Визенталя [298] врач Ариберт Хайм [296] , однако нет сведений о том, знали ли власти о его прежней деятельности. Некоторые из переселенцев по заказу правительства занимались антисемитской пропагандой, другие, как предполагали израильтяне, развивали египетскую ракетную программу. В 1960-х годах необходимость в немецких иммигрантах уменьшилась благодаря помощи со стороны СССР, и отношение к ним со стороны государства ухудшилось [297] . В интервью немецкой газете в 1964 году Насер заявил: «Ни один человек, даже самый глупый, не воспринимает серьёзно ложь о шести миллионах евреев, убитых в Холокосте » [299] [300] [301] . Неизвестно о том, чтобы он когда-либо ещё раз публично ставил вопрос о числе жертв «окончательного решения еврейского вопроса», вероятно, не сделав этого под давлением собственных советников и ГДР [302] .

Региональное лидерство

Благодаря своим политике и речам, выражавшим арабские чаяния, Насер вдохновил несколько националистических революций в арабских странах [303] . Он определил политику своего поколения и предпочитал непосредственное общение с массами, а не с властями [290] . Степень регионального влияния Насера заставила новых националистических лидеров искать хороших отношений с Египтом с целью усилить свою поддержку в народе [304] .

Этатистская система управления государством, выстроенная Насером на родине, в различной степени распространилась практически на все арабские республики [23] [305] . Первый президент Алжира Ахмед бен Белла был стойким последователем Насера [306] . Абдалла ас-Саляль сверг короля Северного Йемена Мухаммеда аль-Бадра во имя арабского единения [166] . Перевороты в Ираке в июле 1958 года и Сирии в 1963 году также были вдохновлены президентом Египта [307] . Муаммар Каддафи , в 1969 году свергший ливийского короля Идриса , считал Насера своим героем и после его кончины стремился сменить его в роли «лидера арабов» [308] . В том же году его сторонник полковник Нимейри захватил власть в Судане [309] . помогало Насеру распространять его панарабские взгляды по всему арабскому миру [310] [311] [311] .

Personal life

В 1944 году Гамаль женился на 22-летней Тахье Казем, с братом которой он дружил. Девушка происходила из обеспеченной ирано-египетской семьи [312] . После свадьбы чета переехала в дом в каирский пригород Маншият аль-Бакри, где и прожила большую часть жизни. Офицерская должность Насера давала хороший по местным меркам заработок [14] . Иногда муж и жена обсуждали дома политику, но чаще всего Гамаль отделял работу от семьи [313] . Он предпочитал проводить свободное время со своими детьми: дочерьми Ходой и Моной и сыновьями Абдель Хакимом, Халедом и Абдель Хамидом [314] .

Несмотря на то, что Насер был приверженцем секуляризма , он был набожным мусульманином и в 1954 и 1965 годах совершал хадж в Мекку [315] [316] . Президент Египта пользовался репутацией неподкупного [317] [318] [319] , что ещё больше увеличило его популярность в стране и в арабском мире [320] . Гамаль увлекался шахматами, любил американские фильмы, журналы на арабском, английском и французском языках и классическую музыку [321] . Он работал по 18 часов в день и редко брал отпуск [259] .

Notes

- ↑ Объединённая Арабская Республика (ОАР) была создана в 1958 году как союз Сирии и Египта. После того, как в 1962 году Сирия вышла из союза, Египет продолжал использовать термин ОАР до 1971 года.

- ↑ 1 2 Vatikiotis, 1978 , pp. 23–24

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , pp. 12–13

- ↑ Stephens, 1972 , p. 26

- ↑ Stephens, 1972 , pp. 28–32

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Alexander, 2005 , p. 14

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Abdel Nasser, Hoda A Historical Sketch of Gamal Abdel Nasser . Bibliotheca Alexandrina . Дата обращения 23 июля 2013.

- ↑ Joesten, 1974 , p. nineteen

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Litvin, 2011 , p. 39

- ↑ Alexander, 2005 , p. 15

- ↑ Joesten, 1974 , p. 66

- ↑ 1 2 Alexander, 2005 , pp. 19–20

- ↑ Stephens, 1972 , p. 32

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Alexander, 2005 , pp. 26–27

- ↑ 1 2 Aburish, 2004 , pp. 11–12

- ↑ 1 2 Alexander, 2005 , p. sixteen

- ↑ The Books Gamal Abdel Nasser Used to Read, 1. During his Secondary School Years . Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Дата обращения 20 августа 2013.

- ↑ Talhami, 2007 , p. 164

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Aburish, 2004 , pp. 15–16

- ↑ 1 2 Alexander, 2005 , p. 20

- ↑ Reid, 1981 , p. 158

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. 15

- ↑ 1 2 3 Cook, 2011 , p. 41

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. sixteen

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. 18

- ↑ Nutting, 1972 , p. 20

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. 22

- ↑ Stephens, 1972 , p. 63

- ↑ 1 2 Aburish, 2004 , p. 23

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. 24

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Aburish, 2004 , pp. 25–26

- ↑ Heikal, 1973 , p. 103

- ↑ 1 2 Brightman, 2004 , p. 233

- ↑ Dokos, 2007 , p. 114

- ↑ Pollack, 2002 , p. 27

- ↑ Gamal Abdel Nasser Writings . Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Дата обращения 24 июня 2013.

- ↑ 1 2 Heikal, 1973 , p. 17

- ↑ 1 2 3 Aburish, 2004 , pp. 27–28

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. thirty

- ↑ 1 2 Aburish, 2004 , p. 32

- ↑ 1 2 Aburish, 2004 , p. 33

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. 34

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , pp. 34–35

- ↑ 1 2 3 Aburish, 2004 , pp. 35–39

- ↑ Nutting, 1972 , pp. 36–37

- ↑ Stephens, 1972 , p. 108

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. 41

- ↑ Nutting, 1972 , pp. 38–39

- ↑ Dekmejian, 1971 , p. 24

- ↑ Stephens, 1972 , p. 114

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. 46

- ↑ 1 2 Aburish, 2004 , p. 45

- ↑ 1 2 3 Aburish, 2004 , pp. 46–47

- ↑ Kandil, 2012 , p. 23

- ↑ Kandil, 2012 , p. 22

- ↑ 1 2 Aburish, 2004 , p. 51

- ↑ 1 2 Kandil, 2012 , p. 27

- ↑ Nutting, 1972 , p. 60

- ↑ Kandil, 2012 , p. 32

- ↑ Kandil, 2012 , p. 33

- ↑ Kandil, 2012 , p. 34

- ↑ 1 2 Kandil, 2012 , p. 35

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. 52

- ↑ Kandil, 2012 , p. 36

- ↑ Kandil, 2012 , p. 38

- ↑ Kandil, 2012 , p. 39

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , pp. 52–53

- ↑ 1 2 Rogan, 2011 , p. 228

- ↑ 1 2 Aburish, 2004 , p. 54

- ↑ Brown, 2000 , p. 159

- ↑ 1 2 Atiyeh & Oweis, 1988 , pp. 331–332

- ↑ Jankowski, 2001 , p. 32

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. 56

- ↑ Aburish, 2004 , p. 239