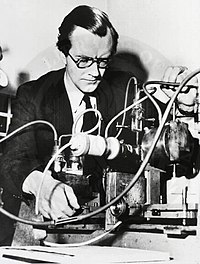

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins ( Eng. Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins , December 15, 1916 - October 5, 2004 ) - English physicist and molecular biologist , 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (with James Watson and Francis Crick ) "for discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and their significance for the transfer of information in living matter. " He contributed to areas of scientific knowledge such as phosphorescence , isotope separation , optical microscopy and X-ray diffraction , and improved radar . Maurice Wilkins is widely known for his work on determining the structure of DNA at King's College London.

| Wilkins Maurice | |

|---|---|

| Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins | |

| |

| Date of Birth | December 15, 1916 |

| Place of Birth | Pongaroa , New Zealand |

| Date of death | October 5, 2004 (87 years old) |

| Place of death | Blackheath, London |

| A country | |

| Scientific field | biophysics |

| Place of work | University of California, Berkeley |

| Alma mater | University of Birmingham Cambridge university |

| Academic degree | and |

| supervisor | John randall |

| Known as | DNA structure discovery |

| Awards and prizes | |

Content

Birth and primary education

Wilkins was born in Pongaroa, New Zealand , where his father, Edgar Henry Wilkins, worked as a physician. His family moved there from Dublin, where his paternal and maternal grandfathers were, respectively, the director of the Dublin High School and the head of the police station. Wilkins moved to Birmingham, England when Maurice was 6 years old. He later attended Wylde Green College, then went to King Edward's School from 1929 to 1935.

Academic Career, 1936–50

Wilkins went to St. John, Cambridge , in 1935. He studied physics, successfully passed the science degree exam, and received his bachelor 's degree in 1938. One of Wilkins's teachers at St. John's College was Mark Olyphant , who received the Department of Physics at Birmingham University and appointed John Randall is his co-worker. Wilkins became a graduate student at Randall University of Birmingham. In 1945, they published three articles in the Royal Society of Phosphorescence and Electronic Traps. Wilkins received his doctorate for these works. [one]

During World War II, Wilkins improved the radar curtains in Birmingham, then worked on the separation of isotopes in the Manhattan Project at the University of California at Berkeley (1944-1945). [2]

Meanwhile, Randall was invited to the Department of Physics at St Andrews University , Scotland. In 1945, he appointed Wilkins to the post of assistant to the Department of Biophysics at St. Andrews University. Randall negotiated with the Medical Research Council (MRC) to create a laboratory for applying experimental physical methods to biological problems (combining these two disciplines into biophysics was a new idea at that time). In 1946, Randall was appointed professor of physics at Wheatstone at King's College, University of London, where the Biophysics Division was founded by the Medical Research Council. He brought Wilkins with him as an assistant director of the department. In addition, researchers who were experienced in both the physical and biological fields of knowledge were invited. It was supposed to cover as many scientific methods as possible in order to find the most promising of them and focus on it. Wilkins, as the scientist with the widest experience in the physical sciences and assistant director of the department, had basic ideas about various projects besides those that were directly in his charge, including several types of optical microscopy. [1] King's College received funding for the construction of entirely new departments of physics and engineering, whose storage facilities were destroyed by bombing during the war. The Department of Biophysics, which included several experimental and one theoretical group, moved to new buildings in early 1952. The laboratories were officially opened by Lord Cherwell on June 27th. Wilkins article in the journal Nature describes two departments (physics and engineering), which is consistent with his leading role in the College. [3]

The first phase of working with DNA, 1948–50

At Royal College, Wilkins studied, among other things, the work of X-ray diffraction on ram sperm and on DNA obtained from the thymus of a calf by Swiss scientist Rudolf Signer. Signer DNA was more intact than previously obtained. Wilkins found that from a concentrated solution of this DNA preparation, it is possible to obtain fine fibers containing the highly ordered DNA necessary to obtain diffraction images. [4] Using carefully folded DNA fibers and maintaining their hydrated state, Wilkins and his student Raymond Gosling obtained x-rays that showed that the long, thin DNA molecules in Signer's samples had a regular structure similar to a crystalline one. Gosling later said: “The moment when ... I first saw these clear diffraction maxima ... appearing on a film in a developing solution was a real discovery, eureka ... We realized that if DNA is genetic material, then we showed that genes can crystallize! ” [5]

The initial phase of work with x-ray diffraction of DNA at King's College was made in May or June 1950. One of the x-ray images taken at that time was demonstrated at a conference in Naples in 1951, interested James Watson [1] and encouraged him to write: Suddenly I was delighted with chemistry ... I began to wonder if I could join Wilkins' work with DNA. " [5] At the same time, Wilkins also introduced Francis Crick to the importance of DNA research. Creek advised him to work with proteins with the words: "It would be nice for you to find yourself a good protein." [6]

Wilkins knew that an exact experiment with purified DNA fibers required more advanced x-ray equipment. To do this, he acquired a new x-ray tube and a micro camera. He also proposed to Randall that Rosalind Franklin , who was soon to be invited to work on protein solutions, would join the study of DNA. [one]

In the summer of 1950, Randall arranged for a three-year research collaboration that could bring Rosalind Franklin to his laboratory. Franklin lingered, finishing her work in Paris. At the end of 1950, Randall wrote Franklin, saying that she should not miss the opportunity to continue the work begun by Wilkins [1] and to do an X-ray study of DNA fibers obtained by Signer.

Rosalind Franklin at King's College

In early 1951, Franklin finally arrived at King's College. Wilkins was on vacation and did not attend the welcoming meeting at which Raymond Gosling replaced him along with Alexander Stokes. The latter was supposed to solve a fundamental mathematical theory that explains how a spiral structure refracts x-rays . No one in the laboratory worked with DNA at the time for several months; a new x-ray tube stood idle waiting for Franklin. She completed an experiment with DNA from Signer’s lab, Gosling began to work under her supervision as a graduate student (PhD student), and Franklin was fully confident that she led the X-ray diffraction project. On the other hand, Wilkins, returning to the lab from vacation, was confident that Franklin would work with him and that they would work together on the DNA project he had begun.

The confusion about the role played by Franklin and Wilkins in trying to resolve the structure of DNA later developed into a strained relationship between these scientists. Responsibility for the situation could be assigned to Randall. In a letter of appointment, he writes Franklin: “Since we are interested in experimental successes (in working with DNA), only you and Gosling will do this.” [1] However, Randall never told Wilkins about his decision to give Franklin exclusive authority on the DNA project, and Wilkins studied the letter only years after Franklin's death. He later wrote: “My opinion is very clear: Randall was wrong when he wrote Rosalind that Stokes and I want to stop our work with DNA, without coordination with us. After that. As Raymond [Gosling] and I received a clear radiograph, I really wanted to continue this work ... It’s not easy to understand “what really happened” when such a respected scientist [Randall] behaves like Napoleon ... [but this letter] was fatal to her and for me". [one]

The second (1951–52) and third stages of working with DNA (since 1953)

In November 1951, Wilkins received evidence that DNA in cells, like purified DNA, has a spiral structure. [7] Alex Stokes solved the main mathematical part of the theory of diffraction of a spiral structure and suggested that the X-ray data of Wilkins indicate a spiral structure of DNA. Wilkins met with Watson and Crick and informed them of his results. Together with additional data that Watson heard at a conference at King's College during the Franklin report, this information encouraged Watson and Crick to create their first molecular model of a phosphate backbone in the center. Seeing the model of the proposed structure, Franklin reacted critically to it, justifying the disagreement with two of his observations. First, the experiments of J.M. Galland showed that the CO- and -NH2 groups of nitrogenous bases cannot be titrated , and are probably inaccessible to reagents. Secondly, crystallographic data show that the structural units of DNA are gradually separated by the addition of water, leading to the formation of a gel , and then a solution. Franklin was convinced that the simplest explanation of these phenomena is the hydrophilicity of the outer part of the molecule. Crick tried to convince Wilkins to continue trying to model the DNA molecule, but Wilkins refused.

In early 1952, Wilkins began a series of experiments on cuttlefish sperm. “I ... got much sharper pictures than last year ... When I accidentally met Bragg, I showed him radiographs that clearly showed convincing evidence of the DNA helical structure ... These pictures of sperm samples inspired further research and were of particular interest because sperm “This is a living object, not DNA extracted and purified by chemists.” Wilkins was extremely interested in whether living samples produced significant diffraction patterns, and his studies gave a positive answer to this question. [1] He sent these images to Francis Crick and James Watson, prompting the latter to write: “Wilkins ... received exceptionally excellent x-rays” [DNA]. [8] [9] At the same time, Wilkins did not rule out the possibility of a non-helical structure of the A-form of DNA. [ten]

During 1952, Franklin also refused to participate in attempts to build a model and continued to work on a step-by-step detailed analysis of her diffraction data. In the spring of the same year, Franklin received permission from Randall to transfer her position from King’s College to John Bernal’s laboratory in London ( Birkbeck College ). However, Franklin remained at King's College until mid-March 1953. [one]

Linus Pauling published the alleged structure, which turned out to be incorrect, as it contained the same basic errors made by Watson and Crick a year earlier. Some British scientists feared that Pauling would quickly solve the DNA structure as soon as he realized his mistake and lay the phosphate backbone of the nucleotide chains outside the DNA model.

Since March 1952, Franklin has focused on x-ray data for the less hydrated A-form DNA, while Wilkins continued to work with B-form. He was in a less advantageous position since Franklin had all the good DNA samples. Wilkins received new DNA samples, but they were not as good as the original samples that he received in 1950 and which Franklin continued to use. Most of his new results were obtained on biological samples (for example, sperm cells, in which the percentage of DNA is highest compared to other cells), for the DNA of which a spiral structure was also assumed. In July 1952, Franklin informed him and Stokes that her latest findings cast doubt on the spiral nature of the A-form.

At the beginning of 1953, Watson attended King's College and Wilkins showed him a high-quality X-ray diffraction image on DNA B-form, now known as “Photo 51,” which Franklin received in March 1952. Realizing that Pauling is working on DNA and is proposing a model of its structure for publication, Watson and Crick made another attempt to derive the structure of DNA. Through Max Perutz , his research supervisor, Crick gained access to information from King's College, which included useful information from Franklin about the properties of DNA that she derived from her X-ray experiments. Watson and Crick published their alleged DNA double helix structure in an article in Nature magazine on April 25, 1953. In this article, Watson and Crick mentioned that they were “inspired ... by unpublished results and ideas” by Wilkins and Franklin. [eleven]

The staff of Cambridge and the laboratories of King's College agreed to report the results of their related work in the next three articles of the same issue of the journal. [11] [12] [13]

Sir Lawrence Bragg , director of the Cavendish Laboratory where Watson and Crick worked, made a statement at Guy's Hospital Medical School, London, on Thursday May 14, 1953, which resulted in an article by Ritchie Calder in " The News Chronicle, London, Friday May 15, 1953, entitled “Why are you - are you. Approaching the secret of life. " The news reached New York Times readers the next day; Victor K. McElheny, searching for materials for Watson’s biography, Watson and DNA: Creating a Scientific Revolution, began clipping a six-part article in The New York Times, dated May 16, 1953, under the heading "The shape of the" unit of life "in the cell is studied using x-ray radiation." The article was published in the early edition, but then was cut out to make room for news, which then seemed more important. A long time later, the article appeared in the New York Times on June 12, 1953. Cambridge University student newspaper Varsity also published its own short article about the opening on Saturday May 30, 1953. Bragg's official announcement at the Solva Protein Conference in Belgium (April 8, 1953) went unnoticed by the press.

The third and longest phase of Wilkins' work on the structure of DNA has been going on since 1953. Wilkins led a major project at King's College London to analyze, verify and make important changes to the DNA model proposed by Watson and Crick, as well as to study the structure of RNA. [14] [4]

Personal life

The first time Wilkins married a student at Ruth's art school when he was in Berkeley. They had a son. The second time Wilkins married Patricia Anne Chigi in 1959. Four children were born in this marriage: Sarah, George, Emily and William.

In the years before World War II, he was a member of the "Anti-War Group of Cambridge Scientists." Wilkins was also a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain , but left after the Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939. From recently published papers by British intelligence agencies, it is known that Wilkins was suspected of leaking information about atomic secrets. [1] The case, published in August 2010, shows that Wilkins surveillance ended in 1953. [15]

“After the war, I wondered what I would do next, as I was disgusted by the two bombs dropped on Japanese citizens,” he told the British radio program Encounter in 1999. [sixteen]

In 1992, he signed the “ Warning to Humanity” [17] .

In 2003, Wilkins published his autobiography, The Third Man of the Double Helix.

Recognition of Merit

С 1959 года является Членом Королевского общества. В 1960 году он стал лауреатом Премии Альберта Ласкера Американской ассоциации здравоохранения. В 1962 получил звание Командора Ордена Британской империи. Также в 1962 году он совместно с Уотсоном и Криком был удостоен Нобелевской премии в области физиологии и медицины за установление структуры ДНК. [18] В речи при награждении А.В. Энгстрём из Каролинского института подчеркнул, что «открытие трехмерной молекулярной структуры дезоксирибонуклеиновой кислоты... событие чрезвычайной важности, т. к. дает возможность для понимания в мельчайших деталях молекулярной конструкции, которая определяет общие и индивидуальные особенности живой материи». [nineteen]

В субботу 20 октября 1962 года получение Нобелевской премии Джоном Кендрю и Максом Перуцом, а также Уилкинсом, Уотсоном и Криком было высмеяно в коротком скетче на Би-Би-Си телевидении в программе «Это была неделя, которая была» (That Was The Week That Was).

В 1969 Уилкинс стал Президентом-основателем английского Общества социальной ответственности в науке.

Кроме того, Уилкинс был принят в качестве Почетного члена в Американскую академию наук и искусств, а также в Американское биохимическое общество.

В 1981 году получил звание заслуженного профессора Королевского колледжа Лондонского университета.

В 2000 году Королевский колледж Лондонского университета открыл Здание Франклин-Уилкинса в честь заслуг д-ра Франклин и профессора Уилкинса перед колледжем.

Надписи на скульптуре ДНК, установленной на территории Клэр-колледжа Кембриджского университета на средства Уотсона:

- на основании памятника:

- «Эти цепи расплетаются в ходе репродукции клетки. Гены закодированы последовательностью оснований».

- «Модель двойной спирали создана благодаря работам Розалинд Франклин и Мориса Уилкинса».

- на спиралях:

- «Структура ДНК была установлена в 1953 году Фрэнсисом Криком и Джеймсом Уотсоном, жившим здесь в Клэре».

- «Молекула ДНК имеет две спирально закрученные цепи, которые связаны парами оснований аденин – тимин или гуанин-цитозин».

Основанный в 2002 году Центр Молекулярных биоисследований Оклендского университета был переименован в Центр Мориса Уилкинса. [20]

See also

- Фотография 51

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Wilkins M. The Third Man of the Double Helix: An Autobiography. — Oxford: OUP, 2005. — 314 с. — ISBN 019280667X .

- ↑ DNA and Social Responsibility: Maurice Wilkins: A brief biography (англ.) . Date of treatment November 27, 2015.

- ↑ Engineering, Biophysics and Physics at King's College, London: New Building // Nature. — Т. 170 , вып. 4320 . — С. 261-263 . — DOI : 10.1038/170261a0 .

- ↑ 1 2 Wilkins MHF Nobel Lecture: The molecular configuration of nucleic acids (англ.) . www.nobelprize.org (December 11, 1962). Date of treatment November 27, 2015.

- ↑ 1 2 James D. Watson, The Annotated and Illustrated Double Helix p25

- ↑ Robert Olby; "The Path to The Double Helix: Discovery of DNA"; p354

- ↑ Horace Freeland Judson. The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Biology. — Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1996. — ISBN 0-87969-478-5 ..

- ↑ Robert Olby; "The Path to The Double Helix: Discovery of DNA"; p366

- ↑ James D. Watson, The Annotated and Illustrated Double Helix p180

- ↑ Aaron Klug. The Discovery of the DNA Double Helix // Journal of Molecular Biology. — 2004-01-02. — Т. 335 , вып. 1 . — С. 3-26 . — DOI : 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.015 .

- ↑ 1 2 JD Watson, FHC Crick. Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid (англ.) // Nature. — 1953-04-25. - Vol. 171 , iss. 4356 . — P. 737-738 . — DOI : 10.1038/171737a0 .

- ↑ MHF Wilkins, AR Stokes, HR Wilson. Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids (англ.) // Nature. — 1953-04-25. - Vol. 171 , iss. 4356 . — P. 738-740 . — DOI : 10.1038/171738a0 .

- ↑ Rosalind E. Franklin, RG Gosling. Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate (англ.) // Nature. — 1953-04-25. - Vol. 171 , iss. 4356 . — P. 740-741 . — DOI : 10.1038/171740a0 .

- ↑ Arnott, Struther. "Crystallography News: An historical memoir in honour of Maurice Wilkins 1916–2004"

- ↑ Alan Travis, Home Affairs Editor. Nobel-winning British scientist accused of spying by MI5, papers reveal (англ.) . the Guardian. Date of treatment November 27, 2015.

- ↑ "A Bunch of Genes". Radio National. 4 July 1999.

- ↑ World Scientists' Warning To Humanity (англ.) . Дата обращения 10 мая 2019.

- ↑ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1962 (англ.) . www.nobelprize.org. Date of treatment November 27, 2015.

- ↑ Лауреаты Нобелевской премии: Энциклопедия. Per. с англ.– М.: Прогресс, 1992.

- ↑ Our History | Maurice Wilkins Centre (англ.) . www.mauricewilkinscentre.org. Date of treatment November 27, 2015.

Links

- Уилкинс (Wilkins), Морис // электронная библиотека «Наука и техника»

- Winners of the Nobel Prize: Encyclopedia: Per. from English.- M .: Progress, 1992.