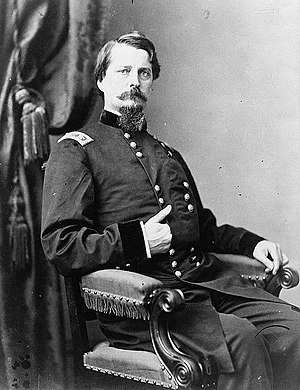

Winfield Scott Hancock ( born Winfield Scott Hancock ; February 14, 1824 - February 9, 1886 ) was a US military man, a graduate of West Point , who participated in the Mexican War and was quartermaster of the 6th Infantry Regiment. After the outbreak of the Civil War, he became general of the federal army, commanded an infantry brigade, and in September 1862 took command of a division on the battlefield after the death of General Richardson . In June 1863 he led the II Corps of the Potomac Army . During the Battle of Gettysburg, took command of the left flank of the army and was wounded while repelling the attack Pickett . Hancock Corps was actively involved in the battles of the Overland campaign and during the siege of Petersburg . After the war he continued his service, participated in the Reconstruction of the South and in the frontier wars. His reputation as a hero of Gettysburg and a supporter ensured him the nomination of a Democratic presidential candidate . He was nominated in 1880, but was defeated by Republican James Garfield .

| Winfield Scott Hancock | |

|---|---|

| English Winfield scott hancock | |

| |

| Nickname | Hancock the Magnificent (Hancock the Superb) |

| Date of Birth | February 14, 1824 |

| Place of Birth | |

| Date of death | February 9, 1886 (61 years) |

| Place of death | |

| Type of army | infantry |

| Years of service | 1844–1886 |

| Rank | major general |

| Commanded | II Corps of the Potomac Army |

| Battles / Wars | US-Mexican War , Civil War |

| Retired | presidential candidate during the 1880 election . |

Early years

Winfield and his twin brother Hilary Baker Hancock (1824-1908) were born on February 14, 1824, in the Pennsylvania village of , northwest of Philadelphia. They were the sons of Benjamin Franklin Hancock (1800–1867) and Elizabeth Hawksworth Hancock (1801–1879). Winfield was named after Winfield Scott , the famous American general. The Hancock and Hawksworth families lived in Montgomery County for a long time and were descendants of people from England, Scotland and Wales. Elizabeth Hawksworth's grandfather was John Hawksworth ( Hoxworth or Hawkesworth ), who settled in Montgomery County in 1728. He married a certain Jenkins from a nearby farm, and their son Edward became the father of Elizabeth. Richard Hancock, the father of Benjamin Hancock, was a sailor who married a tartan Anne-Marie Nash and settled a few miles from the Hawksworth farm. At the time Winfield was born, his father was a schoolteacher. A few years later he moved with his family to the district center of Norristown and became a lawyer. Benjamin also served as deacon in the Baptist church and participated in the municipal government. Six years after the twins, the third son, John (1829–1912), was born in the family, and all three grew up in Norristown [1] .

Winfield first studied at the Norrison Academy with his brother, but then transferred to a public school. At 15, he was honored to read the Declaration of Independence at the celebration of July 4, 1839. In 1840, Congressman , a lawyer and a Democrat , like Winfield's father, gave him a recommendation for admission to the military academy of West Point . Benjamin Hancock at first did not approve of this choice for religious reasons, but friends and, probably, the Baptist pastor persuaded him to give up. On March 31, 1840, Winfield Hancock signed his consent to enter the Academy and thus tied his fate to the US Army, where he served from that moment until his death for 45 years [2] .

In June, Hancock passed the entrance exam and was sent to field camp for two months, and classes began in the fall. The class in which he fell did not become famous - besides him, only two students of this class became famous during the subsequent civil war: Alfred Plezonton and Alexander Hayes . William Franklin , a close friend of Hancock in the future, was a class older. William Rosestreet , John Pope , Lafayette Mac-Law, and James Longstreet studied in two classes over the years . William Smith (also in the future friend of Hancock) and Charles Stone studied under the class, and George McClellan and George Pickett under two classes under the school . Hancock didn’t stand out in his studies; he received the best marks for drawing, geology and infantry tactics. June 30, 1844 Hancock graduated from the 18th Academy in terms of progress in his graduation . Since he found himself in the bottom third in terms of academic performance, he was not given the right to choose the type of troops and assigned him to infantry: he received a temporary rank of second lieutenant and was determined in [3] .

From 1844 to 1845, Hancock served in Fort Towson on Indian territory, and from 1845 to 1847 he served in the recruit service . Relations between whites and Indians at Fort Towson were calm, and the service of Hancock proceeded uneventfully [4] [5] .

Service in Mexico

In the spring of 1846, the war began with Mexico , and Hancock thought about joining the active army. In September, he was given the permanent rank of second lieutenant (retroactively of June 18). The authorities believed that Hancock was more useful in the recruitment service than in Mexico, so at the beginning of the year he was sent to Kentucky to collect recruits for the 6th Regiment, and in March he was sent with recruits to St. Louis . From there he was returned to Kentucky. On May 5, Winfield wrote to his brother that he had just submitted an application for transfer to Mexico, but he doubted that he would be approved. He actually received a refusal, but sent several more requests, and for some reason the command decided to meet them: on May 31, he was ordered to go with recruits to the location of the 6th infantry regiment to Mexico. On June 21, Hancock left Cincinnati , arrived in New Orleans, and from there July 13 to Veracruz . At this time, the Scott Mexican campaign was already under way, the American army was advancing on Mexico City, and it was during these days that it stood in Puebla . Already on July 14, Hancock went to Puebla with 2,500 men, whom General Franklin Pierce led to Scott's reinforcement. The detachment arrived in Puebla on August 8, and already on August 7, Scott began a march to Mexico City [6] .

The 6th Infantry Regiment was listed as part of the William Worth Division. The division left Puebla on August 9 and after three days of march entered the Mexican valley. On August 20, the Mexicans were defeated in the Battle of Contreras , while the Worth Division at that time blocked the Mexican garrison in San Antonio. Worth sent the 6th Infantry, along with Newman Clark's entire brigade, bypassing Mexican positions to attack the retreating enemy. The Mexicans were put to flight. Pursuing them, the 6th Infantry advanced to the enemy positions at Churubusko. The battle began at Churubusko - the first serious battle in the career of Hancock. His regiment forced the channel Churubusko and took Mexican fortifications with a bayonet attack. Hancock received a minor wound, which he didn’t even notice. During the battles of San Antonio and Churubusco, he was given the temporary rank of first lieutenant, dated August 20 [7] .

The battle was followed by a short truce, but on September 7 it was terminated and Scott attacked enemy positions from the Royal Mills (Molino del Rey). In the battle of Molino del Rey , the Clarke brigade lost a third of the privates and half of the officers. Hancock was injured when he commanded all his company. The injury was complicated by fever, which is why Hancock was unable to participate in the storming of Chapultepec Castle . His strength was only enough to monitor the course of the battle from the roof of the house next to the camp. He wrote to his brother that he would always regret that he could not participate in the assault. Hancock returned to service several days later, when the American army entered Mexico City. The fighting on this stopped [8] .

When the capital of Mexico was taken, the Hancock regiment stood in the city for 9 months until the signing of the peace treaty in 1848. At this time, Hancock's company was headed by First Lieutenant Lewis Armistead . Henry Het also arrived at the regiment, and Hancock became close friends with both. “Armistead, Hancock and I were rowdy,” he recalled later, “and there wasn’t even more fun on our fights”. Het and Hancock were often invited to visit Mexican “signorites,” “and all thanks to Hancock, in whom these signorites were in love,” Het wrote. Soon a peace treaty was signed with Mexico, and the army was sent to Veracruz. At this time, June 30, 1848, Hancock officially became quartermaster of the regiment. From Veracruz the regiment was sent to New Orleans, from there to St. Louis , where it was crushed into companies and scattered around the frontier [9] .

Interwar Period

After the war, Hancock remained in the position of quartermaster of the regiment and was sent to Wisconsin at , from where he went east, accompanying Henry Heth, whose health was severely damaged in Mexico. They arrived in New York, where on May 10, 1849, they went to the theater and witnessed the , during which 22 people were killed. Hancock and Het did not suffer. The next day, both officers were invited to dinner at General Winfield Scott, after which Het went to Richmond, and Hancock returned to Fort Crawford [10] .

At the end of the year, Major Don Carlos Buell , Hancock's friend at West Point, introduced him to Elmira Russell (1832–93), the daughter of merchant Samuel Russell, and already on January 24, 1850 they were married at the House of Russells in the presence of Reverend Byuela and Orlando Wilcox . General William Harney and his wife also attended the wedding. On October 29, 1850, their first child, Russell (1850–1884), was born in the Hancock family. Henry Het met Hancock in 1852 and noticed that he had changed a lot - he refused nightly adventures, became a happy family man and faithful husband [11] .

Only on November 5, 1855, Hancock received the rank of captain of the quartermaster service, and was not very pleased with this, because he did not like this type of activity. In February 1856, he and his family were sent to Florida, in Fort Myers. The Third Seminole War had just begun, and the fort was the main base of the American army in the region. Hancock’s responsibility was to ensure the supply of troops. The living conditions were harsh, and Orlando Wilcox called the Hancock House “an oasis in the desert” for all officers. On February 24, 1857, Hancock had a daughter, Ada, who is considered the first child born in Fort Myers. When the situation in Florida improved, the command transferred General Harney to Kansas in Fort Leavenworth , who took Hancock with him. In Kansas, Hancock spent 9 months, in particular, working on the material support of the 1858 Mormon expedition . That summer, the 6th Infantry was ordered to be transferred to Florida, and Hancock was in charge of preparing the march. On August 21, the regiment left Fort Bridger and arrived on November 15 in Benicia in California. As long as long-awaited service in California was expected, Hancock requested leave, returned east through Mexico, met his wife in Washington and took her with him. Elmira didn’t really want to go to California, but Lieutenant Colonel Robert Lee advised her to follow her husband, because long separations usually have a bad effect on family life. Elmira followed his advice, and on April 4, 1859, the whole family went to California via Panama [12] [13] .

Upon arrival in California, Hancock settled in Los Angeles and became the chief quartermaster of the Southern District of California. Under his control was all federal property in the region. Meanwhile, Lincoln became president in the east of the country and a conflict began between the northern and southern states, in which California mainly supported the South. On April 24, 1861, news came about the shelling of Fort Sumter . On the same day, Edwin Sumner took command of federal troops in California instead of Albert Johnston . By his order, all federal forces were pulled to Los Angeles, and Hancock was asked to provide transportation and accommodation. Partly because of Hancock’s quick measures, the government managed to keep California under control. Hancock himself in this conflict took the side of the North; he told one of his friends that he was a northerner and would be faithful to his people even if that people were wrong. He wanted to serve in the east and wrote requests for transfer to General Scott and the governor of Pennsylvania, and as a result, on August 3, 1861, he was ordered to go to Washington at the disposal of the quartermaster general [14] .

At parting, officers of the 6th Infantry, who had already left the federal service, had a party with George Pickett, Richard Garnett , Albert Johnston and Lewis Armistead . Armisted gave Hancock the uniform of a major at parting, which he no longer needed [15] .

Civil War

Hancock and his family left San Francisco at the end of August 1861, sailed through New York to Panama, from where they left for Washington by train. He was appointed quartermaster in the headquarters of General Robert Anderson in Louisville, but he sought field service. At this time, General George Maclellan just formed the Potomac Army ; he knew Hancock at West Point and the Mexican War, so he immediately summoned him to his conversation, and after a few days, on September 23, he was given the rank of brigadier general of the volunteer army and assigned the 3rd brigade in the William Smith division. In October 1861, it consisted of four regiments and two sniper companies [16] [17] :

- 43rd New York Infantry Regiment , Colonel Benjamin Baker

- 47th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment , Colonel Tigman Hood

- 49th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment , Colonel William Irwin

- 5th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment , Colonel Amasa Cobb

- 1st Sniper Regiment, companies B and E.

November 29, 1861, John, Hancock's younger brother, joined the 49th Pennsylvania Regiment in the rank of second lieutenant [18] .

In February 1862, the regiments of Winfield Hancock were included in the 4th Corps of the Potomac Army . The 47th Pennsylvania was taken to Florida, and in its place the 6th Manx Infantry Regiment was brought into the brigade. Hancock immediately began to drill his brigade. He knew that in a war many lives depend on the fast execution of orders, so he was a supporter of tough discipline. At the same time, he avoided excessive rigidity, which was characteristic of many officers of the regular army at the beginning of the war. One of his main means of influencing the soldiers was foul language: Hancock learned this from General Harney and, over time, masterfully mastered this art. Some of his expressions were remembered by his subordinates for many years [19] .

Years of service quartermaster taught Hancock to work with the administrative system: he easily handled numerous documents and was able to organize a system of paper work. He knew the procedures of each department and all possible difficulties in working with these departments, was easily guided in all forms and forms, and could understand the state of the unit as well as at the official review. No one has mastered the art of paperwork better than Hancock, says his biographer [20] .

The Hancock family rented a house in Washington in those days, and he occasionally found time for social life. He managed to get to a private reception in Washington, where only members of the government and officers of a rank not lower than Major General were invited. For Hancock made an exception. Mary Todd Lincoln (the wife of the president) told Elmira that the Russells often received Todd in St. Louis and now she had the opportunity to make a gesture of courtesy in response [21] .

Peninsula Campaign

In April 1862, the Peninsula Campaign began: the Army of the Potomac was transferred by sea to the Virginia Peninsula to Fort Monroe, from where the attack on Richmond began on April 4. On the first day of the campaign, the IV Corps (commanded by Erasmus Keyes ) walked about 12 miles without encountering resistance. On May 5, the corps went out to the fortifications of southerners at the turn of the Warwick River and stopped in front of them for a whole month. The Hancock Brigade spent this month in gunfights and reconnaissance sorties, and its abilities were marked by the command, but at that time it was no different from the rest of the brigade commanders. May 4, Southerners retreated from Yorktown to Williamsburg , where they took a defensive position, reinforced by forts. The attack on this position was commanded by General Sumner, who sent a division of William Smith to the attack. Smith's brigades, advancing in the dark through the forest, immediately disrupted the ranks, and Hancock had to personally participate in establishing order. A little later, Sumner canceled the attack [22] .

On the morning of May 5, the battle of Williamsburg began . Hooker's division launched an attack on Fort Magruder and for some time fought alone. The command decided to bypass the enemy’s left flank, and at 11:00, Hancock was ordered to take several regiments, cross the Kab Dam Creek and seize the fortifications on the other side. Hancock took three of his regiments and two regiments of brigade, shifted a mile to the right, and there he crossed Kab Dam Creek along the dike. He sent ahead of the 5th Wisconsin regiment, which, following the instructions of Lieutenant Custer , found a redoubt not occupied by the enemy and captured it. Ahead, a second redoubt (redoubt number 12) was discovered, and Hancock occupied it too. From this position he could clearly see Fort Magruder and the entire position of the enemy, so Hancock decided to continue the offensive. He noticed two more forts ahead and began to wait for reinforcements to attack them, but William Smith ordered him to withdraw to the starting position. Hancock told Smith that it was more profitable to attack in this situation, but Smith insisted on withdrawing. Hancock sent the courier personally to Sumner, but received no response. At 16:20, he told Sumner that he would wait for his answer for some reasonable time, and only at 17:10 he decided to retreat. At that moment he saw the enemy infantry approaching. Since he did not comply with the direct order for withdrawal, in the event of a defeat, the responsibility would fall entirely on him [23] .

Two Virginia regiments of Jubal Airlie and two North Carolynian regiments of Daniel Hill attacked Hancock. Hancock took his pieces back a bit, imitating the withdrawal, then ordered the regiments to turn around, give two volleys at the enemy, and then go into bayonet attack. It was a difficult assignment for recruits, of which the Hancock regiments consisted, but long-term training gave their results, and the team was able to drop the enemy. In this battle, Earley lost 600 men, and the 5th North Carolian Regiment was almost destroyed ['' i '' 1] . Hancock lost 126 people. His actual disobeying of the order was forgotten. On May 6, McClellan told his wife that "Hancock was great yesterday" ( Hanckok was superb yesterday ). This phrase got into the newspapers, and the nickname “Magnificent” stuck to Hancock [25] .

General William Smith in the report noted the brilliant battle plan, its excellent implementation, the competent combination of defense with attack, the stubbornness of privates and the uniqueness of the victory won. Generals Keese and McClellan spoke in the same vein. But, despite the real merits of Hancock, the battle itself was just a poorly organized rearguard skirmish, and advertising the successes of Hancock, the command sought to hide from the public their own miscalculations. Accordingly, the army began talking about the fact that Hancock paid too much attention and that from the McClellan report it follows that no one participated in the battle except for Hancock [26] .

On May 18, the army was re-formed, and Smith's division moved into the VI Corps , commanded by William Franklin, Hencock's friend at West Point. The corps did not participate in the battle of Seven-Pines on May 31 - June 1, as well as in the first battles of the seven-day battle . On June 27, the battle of Gains Mill began north of the Chikahomini River; at the same time, a skirmish began south of Chikahomini, at the positions of the Smith division. Here, the brigade of George Anderson began to attack, who immediately assessed the strength of the enemy’s fortifications and withdrew the attack, but the neighboring brigade of Robert Tumbes continued to advance and attacked the positions of Hancock. This attack was easily repulsed with significant losses for the southerners. The next day, Tumbes attacked Hancock's position again and was repulsed again, losing 150 people, including two colonels [27] .

On the night of June 30, the Army of the Potomac began to retreat to the James River, and Franklin's corps was in the rearguard. At 3 am, he crossed the White-Oak-Swamp swamp and took up positions on the southern edge of the swamp. In the afternoon, the division of Thomas Jackson came to the swamp, but Jackson did not attack, but confined himself to artillery shelling of enemy positions. On July 1, the Potomac Army retreated to Malvern Hill, but Franklin's corps took the extreme right flank of the position and did not participate in the battle that day. After the battle, the army retreated to Harrison Landing, where it stood a month and a half, and then the campaign was curtailed. Hancock was among those few officers who earned a good reputation during the campaign. He fought a bit, and his team lost only 200 people, but there were few victories in that campaign, so Hancock's few successes attracted attention [28] .

Maryland Campaign

On August 3, General McClellan received an order to return the army from the Virginia Peninsula to Washington, so on August 16 Franklin’s corps left the camp at Harrison Landing, passed through the peninsula, and arrived in Newport News on August 21. On the same day, the corps sank on transports and was sent to L'Aquila Creek, but the corps of Burnside and Porter were already unloaded at this port, so the VI corps was sent to Alexandria. At this time, the federal Virginia Army fought General Lee's Severo- Virginia army at the turn of the Rappahanok River , and its commander-in-chief, General John Pope , requested reinforcements, but McClellan was not interested in saving Pope. On August 27, Colonel Haupt personally arrived at Hancock with a paper from Henry Halleck ; Haupt was tasked with transporting a supply train for the Virginia Army, and he was looking for an escort. McClellan did not help him, but Hancock agreed to help and sent with him the 2nd New Jersey Infantry Regiment [29] .

In early September, the North Virginia Army crossed the Potomac and began the Maryland campaign . McClellan moved the Army of the Potomac to the west along three roads. On September 13, he learned that the enemy had taken a position in the gorges of the Southern Mountains and that part of his divisions was under Harpers Ferry , which allowed him to be crushed piecemeal. At 18:20, Franklin’s corps was ordered to go to the Krampton Gorge, the southernmost of the three gorges, and unlock Harpers Ferry. The gorge was only 12 miles from Franklin’s position and was unprotected that night, but Franklin started the march only on September 14 and came out to the gorge at noon. Slokam 's division attacked and conquered the gorge , after which Franklin didn’t do anything. The next morning, Smith's division crossed the Southern Mountains and headed for Harpers Ferry, but at this very time the city’s garrison surrendered to Thomas Jackson. Franklin stopped the offensive and remained in his position until the morning of September 17th [30] .

On September 17th, the battle of Entity began . McClellan attacked the enemy I and XII corps from the north, and then the second corps of General Sumner in the center. Franklin's corps arrived at the battlefield around 10:00, when the Sumner attack began. The divisions of French and Richardson advanced on the position of the southerners along the Sunken Road, and behind them stood artillery without cover. Smith's divisions were ordered to provide security for the guns, and he assigned it to Hancock. At this time, divisional general Richardson was mortally wounded, and McClellan ordered Hancock to take command of the division. When Hancock arrived at 3:00 pm to the division, she took up a position along the Sunken Road, which had just been captured. At that time, the division was exhausted by two campaigns, and its number was only 2,100 people. It consisted of the brigades of General Caldwell , General Meager and Colonel Brooke. Hancock immediately brought order to the ranks, summed up the artillery and was able to repel the attack of a small detachment of the enemy. The next morning, the armies still held their positions, but McClellan ordered not to resume fighting and wait for reinforcements. On the night of September 19, Lee took the army for the Potomac [31] .

McClellan kept the army in Sharpsberg for a month and only on October 16 ordered two reconnaissance operations: the Humphreys division transferred the Potomac from Shepherdstown, and the Hancock's division entered Harpers Ferry and captured Charlestown . Here McClellan personally appeared at the location of the division of Hancock. After making sure that the enemy did not leave the Shenandoah Valley , he ordered both divisions to return for Potomac. Only on October 26, the army launched a general offensive and in 8 days passed the Potomac. Hancock's division occupied the Snickers Gap gorge in the Blue Ridge Mountains . The army reached Warrenton , where in early November, McClellan was removed from command. Hancock had mixed feelings about this; McClellan was his friend and made him a brigade and divisional commander, and Hancock was always loyal to his friends. He wrote to his wife that the army was dissatisfied with the replacement and considered McClellan’s resignation unfair. But he considered it useless to resist this decision and told friends that they served only their country [32] .

Fredericksburg Campaign

After the resignation of McClellan, army command took Ambrose Burnside , which brought the corps into three "grand divisions". General Sumner became commander of the Right Grand Division, and his II Corps was headed by Major General Darius Couch . Burnside developed a plan of attack through Frederiksberg , and on 14 November his army began a march. The first was the Sumner Grand Division, and the Hancock Division was at the forefront. Moving in an accelerated march, the division had already reached the Rappahanki River on November 17, but the pontoons for the crossing were not delivered on time. Sumner was ready to cross without them, but Burnside forbade him. The army stopped waiting for the means of the crossing, and this wait lasted until December. On November 29, 1862, Hancock was promoted to Major General of the Volunteer Army, and on November 30 he was promoted to Major of the Regular Army [33] .

Meanwhile, Burnside decided to conduct a frontal attack on enemy positions across the river. On the night of December 9, Sumner outlined a plan of attack to his officers, who for the most part expressed dissatisfaction with this plan. Burnside summoned the officers to his headquarters and held a conversation with them, while Hancock explicitly stated that it would be extremely difficult to take the heights beyond the river. December 12, the division crossed the river. On December 13, the battle of Frederiksberg began : the Couch Corps launched the first attack, while its commander put the French Division in the first line, and the second, with a distance of 200 meters, Hancock's division. The attack began at 11:00. The French division immediately came under fire from batteries standing on the heights of Mari, and then under rifle fire from an enemy brigade, which took up a position behind a stone wall at the foot of the heights. French managed to get to the wall 40 or 50 meters, but his attack was repelled. Then Hancock sent a Zuk brigade to attack - she approached the wall at 100 meters, then lay down. Zook lost 527 people out of 1532. After that, the Irish brigade went on the attack, which approached the wall 40 meters, and the 69th New York regiment broke through 25 meters, but Maher retreated, losing 545 people from 1200. Third, Caldwell's brigade went on the attack, which lost 950 people, and among them Caldwell’s wounded. In total, the division of Hancock lost more than 2,000 men out of 5,000, among them 156 officers [34] .

December 15, the army retreated for Rappahanok, Hancock took leave and went to the family in St. Louis. Because of vacation, he missed the conflict between Burnside and his generals, as well as the “ Mud March ”, during which his division was commanded by Samuel Zook [35] .

Chancellors Campaign

In the spring, Joseph Hooker became the army commander, who brought order to her and, in particular, developed a system of symbols-stripes for corps and divisions. The 2nd Corps received a trefoil symbol, and the 1st Division received red trefoil stripes. On April 27, 1863, Hooker launched an offensive: XI, XII, and V of the Fifth Corps crossed Rappahanok and Rapidan, advanced to the flank of the enemy army and stopped on April 30 at the Chancelorsville Plateau. On April 28, Couch sent Hancock and French divisions across Rappahanki over United States States-Ford, and they also went to Chancelorsville. May 1, the army continued to attack on three roads. The Sykes division was advancing in the center, and the Hancock divisions were ordered to follow. Around 11:00, Sykes exchanged fire with Lafayette MacLouse's division - the battle of Chancellorsville began [36] .

Hancock led his division (5,900 men) to join up with the Sykes division, but at that time, an order came for all units to retreat to the fortifications on the Chancelorsville Plateau. Both Couch and Hancock found the order erroneous, but they obeyed and withdrew the divisions. As a result, Hancock deployed his division on the edge of a plateau near Chancellor's house, facing east, to the left of Sykes division. Two regiments of Nelson Miles turned around in front of the rifle chain. Southerners divisions of Henry Heth attacked this position several times, but were repulsed by Miles. On May 2, Sykes was led to the rear, to the right of Hancock, Giri's division stood up, and to the left, French's division. Southerners held small sabotage from the front all day, but Miles held the position. At 5:00 pm, Thomas Jackson attacked and defeated the XI Army Corps, but nothing serious happened at the Couch front. On May 3, the southerners attacked from the west, rejected the corps of the Seekles and the Giri division, and from the east, General Makloz attacked the positions of Hancock, but to no avail. Federal divisions began to depart from the plateau to the north, and soon only the Hancock division remained on the plateau. Hancock kept two brigades (Zuka and Brooke) front to the east, and two (Maher and Caldwell) turned the front to the west; Thus, a corridor was formed, along which the remnants of the Cycles' corps and the Geary division had moved to the rear. In his position Hooker managed to collect about 16 guns [37] . The division was under fire from three sides. The order to retreat was received only at 10:00. Hancock turned and sent batteries to the rear, followed by infantry. In this phase of the battle, his division restrained the offensive of the entire enemy army, although this army was already exhausted by the battle [38] .

Subsequently, testifying to the war investigation committee, Hancock said that the battle, in his opinion, was lost because the army stopped at Chancellorsville. It was necessary to immediately continue the advance to the east, to leave the flank to the Banks-Ford ferry and connect with the Sedgwick corps. In this case, Hancock argued, all maneuvers would have been crowned with success [39] .

After the battle, General Darius Couch lost faith in Hooker as a commander and left the 2nd Corps on May 22. Hancock was the most obvious candidate for his place. He was considered the best divisional commander in the corps and the best commander in this army. The whole army understood that this was a logical and well-deserved promotion. The place of the commander of the 1st division was occupied by John Caldwell, the 2nd division was still headed by John Gibbon, and the 3rd by William French. The corps chief of staff, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Morgan [40] also remained in his place.

Gettysburg Campaign

In mid-June 1863, the command became aware that the entire North Virginia army had gone into the Shenandoah valley, so the Army of the Potomac was ordered to change its deployment. On the night of June 14, the Hancock Corps turned down camp at Falmouth and proceeded through Aquila Creek and to Centerville. From there, on June 31, he moved to the gorge of Torufeir-Gap. June 25 came the order to start a march on Gainesville and on to the Potomac River. When the corps approached the village of Highmarket, he found himself on the way of Jeb Stuart's cavalry, which began his raid through the rear of the Potomac army that morning. Stewart launched several gun volleys across the hull and retreated, losing a whole day of his time. Ignoring Stewart, the corps arrived at Gum Springs, where it was joined by several New York regiments captured at Harpers Ferry and released on exchange. The regiments were commanded by Alexander Hayes . Since General French left the division on June 24 and led the Harpers Ferry garrison, Hancock transferred his division to Hayes (and the New York regiments to George Willard). On the same day, Brigadier General Alexander Webb arrived at Hancock’s disposal, and the Corps Commander assigned him to the Philadelphia Brigade [41] .

On June 26, Hancock's corps crossed the Potomac and on June 28 approached Frederick . On that day, Commander Hooker was dismissed and George Meade took his place. On June 29, at 8 in the morning, the corps began a march to the north and by 10 pm it was more than 30 miles, which is considered the longest one-day transition of that war. The corps arrived at Uniontown and stood there all day on June 30, awaiting the approach of the Corps V. On the morning of July 1, the Hancock corps moved to Teneytown and camped at 11 am. Hancock visited the headquarters of Mead, returned from there to his headquarters, and at 12:30 he unexpectedly received an order to go north and cover the flank of the Reynolds Corps. Almost immediately, Mead and the chief of staff, Butterfield , came to his tent. They reported that the Reynolds and Howard corps had gotten involved in the Battle of Gettysburg and that Reynolds had been killed. Mead didn’t have a reliable man at Gettysburg, so he ordered Hancock to go to Gettysburg and take command on the battlefield. The official order was made immediately at 13:10. Hancock remarked that Generals Howard and Seekles were older than him ['i i ’’ ’] 2 , but Meade replied that he was authorized by the military secretary to appoint commanders without regard to seniority. Hancock doubted that this method would work, but he complied and left at 13:30 with his headquarters in Gettysburg [43] .

Hancock arrived at Gettysburg supposedly at 3:30 pm ['' i '' 3] , at that moment when the front of the army began to crumble and the first fugitives began to retreat to Cemetery Hill. On Cemetery Hill, Hancock met General Howard. There are different versions of their meeting; Hancock himself wrote that he met Howard, notified him that he was taking command, and he agreed with this decision. Howard explained the events differently: he wrote that he proposed to Hancock to head the left flank, and he headed the right flank, and Hancock did not object. In 1864, Howard insisted that he commanded the army until 19:00, when he surrendered command to Slocam . Even later in his memoirs, he claimed that he knew nothing about the appointment of Hancock until 19:00. One of the adjutants [4] recalled that Howard had refused to transfer command. According to Ebner Doubleday , Howard did not surrender command, but asked Hancock to help bring order to the troops [44] [45] .

Gen. Schurz cites the following dialogue between Howard and Hancock [46] :

| “Well, General Howard, I will be second in seniority, but General Meade also ordered me to choose a place to fight for Pipe Creek,” he then glanced around the area from Culps Hill to Round Top and continued, “but I think this is the strongest position I've ever seen, so with your consent I choose it for the battlefield. “I think this is a very strong position, General Hancock, a very strong position.” “Fine, sir, I choose her for battle.” |

From further events it is clear that Hancock still took command: he sent the Wadsworth division to take the height of Culpes Hill on the right flank, and when Geary’s division arrived, he sent her to cover the left flank, although he formally had no right to command units of the XII Corps. John Byuford wrote that Hancock instantly led the army into a superb position to repel a possible attack. Hancock sent Mida a message that he would hold on until dark, and he should decide whether to retreat or hold the position, although the position is not bad. At 5:25 pm, he sent a second message, where he wrote that the position was strong from the front, but it could easily be bypassed from the flank, that the battle subsided and there was nothing to fear until the morning that he could retreat, although the position was not unprofitable. At 18:00, Hancock surrendered command to General Henry Slokam, returned to Tentown, described the situation to Mida, slept for a few hours, and at midnight went to Gettysburg to command his corps [47] .

On the morning of July 2, Hancock led the II Corps to the position and placed it on the Cemetery Ridge to the left of the XI Corps . To the right stood General Corps III Corps. But Seekles did not like his position, so at 14:00 he moved the corps forward, without notifying Mead and Hancock. Hancock and Gibbon watched this movement in bewilderment. “We could not imagine what this meant,” General Gibbon later recalled, “we did not hear any order for an offensive and did not understand why this gap in our line was needed.” According to the recollections of one witness, Hancock and Gibbon exclaimed: “What the hell does Seacles do this ?!” [48] . Mead did not have time to fix it, as at 4:00 pm the Seacles came under attack from Longstreet's corps and began to retreat. Mead ordered Hancock to transfer his left division (Caldwell) to the aid of the Seekles. A little later, Seekles was wounded, and Mead ordered Hancock to also take command of units of the 3rd Corps. The left flank of the army at that time was in mortal danger, and Hancock had to apply superhuman energy (as Jordon put it) to save him. He took the brigade of Willard and personally led her to a dangerous area, where she managed to stop the advance of the Mississippi brigade Barksdale . Then Hancock saw the Wilcox Alabama Brigade advancing on a virtually empty section of his front, and threw Colonel William Colville into the counterattack of the 1st Minnesota Regiment. Hancock managed to keep his position until dark [49] .

On the morning of July 3, the positions of Hancock were quiet. At night, Mead suggested that the enemy was attacking Hancock, but in the morning he decided that the left flank would be attacked. At noon, Hancock, Gibbon, Mead, and Plezonton gathered for lunch at the Gibbon headquarters, and at 1:00 pm the enemy opened a powerful artillery bombardment all along the line. Hancock mounted his horse and slowly drove along his entire front from the right flank to the extreme left to inspire his people. At this time, the Picket attack began: five enemy divisions attacked the positions of Hancock, and the Lewis Armistead brigade almost broke through them at the site of the Webb brigade. Hancock transferred the 19th Massachusetts Regiment and the 42nd New York , and then the rest of the Norman Hall brigade to a dangerous area. The attack was repelled, and Armistead was fatally wounded. Hancock at this time went to the brigade Stennard, to send it to the flank of the enemy, but he already began this maneuver. Hancock began to give orders to the commander of the 13th Vermont Regiment and at that moment was wounded in the groin. He was removed from his horse and laid on the ground, after which he ordered him to remain in place until the end of the battle [50] .

Armistead was injured a few hundred meters from Hancock. He was discovered by Captain Henry Bingham, who said that he was an officer of the headquarters of Hancock and was ready to hand over something to the family of the dying man. Armistead muttered: “Tell Hancock from me that I caused him and you all heavy damage, which I will always regret” [51] .

On Vacation

After the fight, Hancock was carried to the Cemetery Ridge, where Dr. Dugerty with his fingers checked his wound and found a nail ['' i '' 5] and pieces of wood. Hancock decided that the Southerners fired nails instead of bullets and told Mida that his injury was a good sign and it seemed the enemy had an ammunition problem. But the nail hit the body of Hancock from a fractured saddle bullet and almost touched the femoral artery . He was taken to a corps hospital, from where he sent a telegram to his relatives. Hancock's ambulance took them to Westminster, from where he was taken by train to Baltimore and then to Philadelphia. Here came his father and wife. The weather in Philadelphia was hot, but the wound did not heal. On the advice of the doctors, Hancock moved to the cooler Norristown, where military surgeon Lewis Reed calculated the trajectory of the bullet, managed to find it at a depth of eight inches in the patient's body and figured out a way to extract it. After extracting the bullet, Hancock's health quickly began to improve, and within a week he was able to walk on crutches. He went to New York and then to St. Louis , where he spent six weeks [52] .

While Hancock was recovering, the campaigns of Bristo and Mine-Ran passed, after which Mead was condemned for being slow, and Hancock and Gibbon wrote him sympathetic letters. It was rumored that Hancock would be appointed commander-in-chief instead of Mead. Mead wrote to him that he would be glad of such an increase in him, but this is a problematic position, which is not to be congratulated. On December 27, Hancock returned to the corps command, but on January 8, 1864, a special commission decided that he was not ready for field service and was returned to Washington, where the military secretary instructed him to recruit new recruits for the corps. The government hoped to increase the housing to 50,000 people, but in the spring Hancock could only bring it to 27,000 [53] .

On March 22, Hancock was summoned to testify to the Committee on the Conduct of War regarding the course of the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. He gave generally favorable testimony for Mead, although he believed that he should have attacked immediately after repelling Pickett’s attack . The next day, Hancock returned to the army headquarters in Culpeper , and on March 24, the military department issued General Order No. 115, according to which the army was reorganized. I and III corps were reduced, while two divisions of the III corps were transferred to the Hancock corps [54] . Heis's division was disbanded, and as a result, by the beginning of May, the Hancock corps assumed the following form [55] :

- Francis Barlow Division; brigades of Miles, , Frank,

- The division of John Gibbon; brigade Webb, Owen, Carroll

- David Byrney Division; brigade ward and heys

- Gershom Mott Division; brigade Mott and Brewster

Battle of the Wilderness

In the early days of May 1864, General Grant began his Overland campaign to defeat Lee's army. On May 3, when the sun went down, Hancock’s 2nd Corps turned down the camp and after 23:00 stepped out of Stevensburg to the Eli-Ford ferry along two roads. At dawn on May 4, the corps entered Richardsville. The corps of Warren and Sedgwick walked along a parallel road to the Herman-Ford ferry. At 06:30, Hancock informed the headquarters that he was successfully crossing the river [56] . The next day at 07:15, General Meade found out that the enemy had attacked his columns from the west along the Orange-Tenpike road: the battle began in Glushi . According to the original plan, the Hancock Corps was to go from Chancelorsville along the Qatarpin Road and cross Brock Road near Todd Tavern. But after learning of the southerners' attack, Mead ordered Hancock to stop at Todd Tavern and wait for the situation to clear up. This order reached Hancock only at 09:00, when his corps passed Todd Tavern and retired two miles to the west. Hancock stopped the corps and waited for instructions. At 10:00, having familiarized himself with the situation, Grant ordered the Warren Corps to attack the enemy, and Hancock - to take the strategically important intersection of the Orange-Plenk Road and Brok Road. Fearing that Hancock would not have time to go to the intersection, Grant sent the Getty Division there at 10:30, and Hancock ordered him to go to his aid. He received an order only at 11:40. His corps began to march to the crossroads, while Hancock himself went ahead and arrived at the scene shortly after noon. By this time, the Getty had already fought with Henry Heth's division (from E.P. Hill's corps). Hancock again asked for instructions, but the couriers from Mead got to him only at 14:40. However, even at this time, Hancock was not ready to attack; his forward division, commanded by Birney, managed to come to the scene, but the division of Gershom Mott , who was following her, was just coming up and taking a stand. At 15:00, Hancock found out about the failure of the Warren attack, but the command required a decisive offensive from him. Hancock decided to attack with the forces that are: the divisions of the Getty and Byrney in the first line and the division of the Mott in the second. However, at 3:45 pm a new, clarifying order arrived: Mead demanded that the Getty Division advance straight along the road, and the Hancock divisions to the right and left. The fulfillment of this condition required additional time, but the Getty received a direct order to attack. At 4:15 pm, his division went ahead without waiting for Hancock [57] . Hancock sent the Mott division, then the Birney division, and the Gibbon division at 17:00. Barlow's division approached. Now, the entire Hancock Corps (27,000 men), reinforced by the Getty Division (6,000 men), acted against the Heth division, and the balance of forces was 1 in 5 in favor of the federal army [58] .

The position of Heth's division became difficult, but the Wilcox division came to his aid. Yet by 18:00, the Hancock corps was close to victory, although they were not aware of this at the corps headquarters. At 17:50, told Midu that the corps barely holds the position that Hancock can hardly advance and needs reinforcements. By this time, Grant himself decided to send additional forces to help Hancock, but not to transfer them to Hancock, but to attack from the north in the direction of Hill’s left flank [59] .

On May 6, Grant decided to attack at the same time with all corps. Hancock should deliver the main blow: at 04:30 his corps, reinforced by the Getty Division, had to attack the weakest point of the enemy defense - Hill corps, while leaving one division to cover the southern flank. Wadsworth's division must attack Hill in the left flank. To consolidate the success, the two divisions of the Burnside Corps must go into the gap between Hill and Ewell's corps and also attack Hill, joining Wadsworth's attack. Shortly before 05:00, a signal volley sounded, and the Potomac army launched an offensive in two columns. The Hancock Corps, reinforced by the Getty Division, moved strictly along Plenk Road to the west, and the Wadsworth Division began an offensive on Hill’s left flank, moving to join Hancock. Southerners were in a bad position, so they began to retreat almost immediately. Some units stubbornly fired, while others made only a few volleys and immediately withdrew [60] .

At 05:30, Lyman met the joyful Hancock corps at the headquarters. “We drive them great! - He exclaimed, - tell Mida that we are driving them just great. Byrney comes and drives them great-to-lep-no! ”. Meade conveyed his words to Mida, and then returned with the message that Burnside had not yet reached the position of attack. “I knew it,” exclaimed Hancock, “this is exactly what I expected. If he can attack right now, we will break Hill into pieces! ” Meanwhile, his attack gradually exhaled. The Wadsworth division, advancing, mingled with parts of Hancock, creating a crush and confusion. General Birney was forced to stop the attack in order to level the ranks. And at this time, around 06:00, Longstreet's corps came to the aid of Hill [61] .

The Longstreet divisions ( Field and Kershaw ) attacked the frustrated ranks of the Hancock corps and immediately overturned the divisions of Byrney and Mott. Already at 06:20, Lyman requested help from Mida. At 07:00, Hancock informed the army headquarters that they were pushing him hard. By 8:00, the enemy’s attack was exhausted, but Hancock did not receive reinforcements and was forced to do it on his own. He knew that the Field and Kershaw divisions were fighting on his front, but he did not know where Pickett and Anderson's divisions were, and did not rule out that they were avoiding his left flank. Even at 7 am, Hancock, he said, ordered Gibbon to transfer the division of Barlow to the center of the corps, but Gibbon understood from the order that he needed to send only one brigade. Subsequently, this misunderstanding complicated Hancock’s relationship with Gibbon. Around 09:00, news came to Hancock that some parts of the enemy were seen on his left flank, and at the same time information came that his right flank was threatened. And those and other news were subsequently false, neither in such a situation was there a question of continuing the offensive [62] [63] .

When attacking Hill in the morning, Hancock did not notice the clearing of the unfinished railway on his left flank, which could be used to reach the enemy in the flank. Meanwhile, the Southerners intelligence found this road and at 10:00 reported it to Longstreet. He immediately sent several brigades along the glade and attacked Mott's division from the flank. Simultaneously, the division Kershaw struck from the front. Motta Division fled, and the Southerners began to approach the Orange-Plenk Road. Hancock’s entire corps began to retreat, and Byrney advised him to withdraw his troops to the fortifications along Brock Road. By 12:00, the Southerners were confidently advancing, but General Longstreet was wounded by an accidental shot, and this stopped the offensive. After some time, Lyman found Hancock, who was alone sitting behind the line of fortifications. Hancock told Lyman that his corps was exhausted, upset and completely unprepared for the offensive. He insisted that the generals put things in order as quickly as possible, but he understood that the high losses of the officers make this work difficult. Nevertheless, Hancock was sure that at least he could keep the line along the road [64] .

Grant and Mead were still hoping to seize the initiative: at 15:00, Hancock was ordered to attack at 18:00. He replied that it was hardly possible, but promised to do everything possible. Meanwhile, General Lee himself hoped to attack Hancock. As with Gettysburg, he expected to reverse the situation with a decisive frontal attack. At 16:15 Southerners went ahead and managed to break through at the site of the ward brigade. The attackers immediately came under fire from the federal artillery, and then a Brook brigade was transferred to a dangerous area. Breakthrough managed to eliminate. Only at 17:30 Hancock reported that the attack was repelled. He also said that he had squandered all the ammunition, it would not be possible to replenish them quickly, and in this situation, the attack scheduled for 18:00 seemed to him impossible. Mead was forced to agree with his opinion and at 5:45 pm ordered the cancellation of the offensive [65] .

Battle of Spotsvilnény

Unable to break through the defenses of the enemy in the wilderness, Grant decided to change the position. On May 7, the Corps of Warren and Sedgwick were sent to the town of Spotsilvini, where on the morning of 8 May they met with the army of Lee — the battle of Spotsvilnay began . Hancock Corps was the last on Brock Road; in the morning he was stopped at Todd Tavern to cover the right flank of the army. At 3:00 pm, the 3rd Corps of the North Virginia Army , commanded by Jubal Early, accidentally reached its front. After a small skirmish, Earley retreated, but at Mead’s headquarters it was decided that it was here that the enemy was preparing the main attack. Hancock was waiting for a serious attack. “Night came, and the great battle of Todd Tavern never happened,” wrote his adjutant. This delay did not allow Hancock to take part in the fighting at Spotsilvaini on May 8 [66] . It was only on May 9 at 11:15 that Hancock finally became convinced that the enemy had retreated on his front. Grant ordered him to leave the Mott division at Todd Tavern, and the other three divisions to go around the enemy’s left flank. By 19:00, Hancock went into position to attack, but did not dare to attack in the dark. Hancock's offensive alarmed General Lee, who threw Het and Mahone's divisions to meet him. On the morning of May 10, the so-called “battle on the river Po” began; Hancock discovered the Mahone division in front of his front, and Heth's division on the flank. Mead ordered a retreat, and Hancock barely managed to retreat beyond the river. Subsequently, General Humphreys wrote that Hancock had chances to break the enemy’s flank, and Mead in vain canceled the offensive instead of strengthening Hancock with additional forces [67] .

On May 11, Grant decided that the enemy’s weakest point of defense was a protrusion known as the "Mule Horseshoe" and decided to attack him with the forces of the Hancock corps. At 4 pm, Mead ordered Hancock to redeploy. In the evening, Hancock gathered his divisional commanders and outlined to them the plan of the night march. Barlow then recalled that no one had described the enemy’s position, did not name the number of the enemy, did not explain the plan of the attack, who was involved in it, and why this particular place should be attacked. At 21:00 the corps went to the specified position. He had to walk about 35 kilometers in the dark in the rain. The march was difficult, and even the officers were discouraged [68] . At night, the corps took up a position, and at 04:35, Hancock ordered a start. His corps collapsed on the position of the division of Johnson and immediately captured them, the generals Johnson and Stuart were captured. At 05:15, the courier delivered to Grant a report from Hancock: “Our men took the trenches and several hundred prisoners. You can not say how much. This report was followed by others: “More and more than 2000 prisoners,” “I captured Major General E. Johnson and another General Johnston ... they captured General Stewart.” Even cold-blooded Grant perked up noticeably: “I like this kind of news,” he said, “Hancock acts not badly” [69] [70] .

Hancock broke through the center of the Northern Virginia Army and captured the trenches, but its units came into complete frustration, and then came under the attack of the John Gordon Brigade and began to retreat. Hancock was alarmed, he felt that he would be recaptured if no one joined his attack. He asked to enter the 6th corps into battle as quickly as possible. By 06:00, Grant’s advance was completely exhausted. The fighting in the trenches lasted a whole day and subsided in the morning of May 13. The losses of the Hancock corps were enormous, in the battles for the Horseshoe Mule he lost, according to official estimates, 2,537 people [71] .

On May 13, the southerners left the Mule Horseshoe and moved to a spare position. A few days at the front lasted a lull, but on May 17 Grant decided to repeat the attack. Hancock sent to attack the new position of the enemy division of Barlow and Gibbon, but this attack was easily repulsed. Northerners lost 650 people, only about 30 southerners. On May 20, Grant stopped trying and gave an order to march to the North Anna River. In the battles in Glushi and Spotsilvini, Hancock turned out to be the most reliable corps general: Warren was hesitant, Sedgwick was killed, and Wright was the mediocre commander who replaced him, and no one took Burnside seriously [72] .

The attack on Petersburg

On May 20, Grant, in order to lure General Lee from fortified positions, sent the Hancock corps southward, away from the main army, hoping that the enemy would attack the isolated corps. Hancock took a strong position on the Mattaponi River, but Lee did not attack, so on May 23, Hancock went further west. On the same day, he reached the North-Anna River near Chesterfield, attacked the bridge-bridge fortification, captured it, and crossed the river. As a result, Lee's army was between the two parts of the Potomac Army, which was extremely dangerous, and on May 26, after two days of hesitation (and skirmishes, known as the Battle of North Anne ), Grant ordered the withdrawal from a dangerous position. The corps continued its march to the south and in the evening of May 27 went to Hanovertown on the Pomanka River. On May 29, the Potomac Army entered into an exchange of fire with the enemy at the turn of the Totopotomi River, and Hancock was ordered to attack, but his divisions did not find a suitable area for the offensive. On June 1, the advanced units of the Grant ran into an enemy at Cold Harbor and Hancock was ordered to march overnight to the battlefield to participate in a general attack on June 2. Hancock led the corps to the position on time, but the corps was so exhausted by the march that the attack was postponed the next day [73] .

On June 3, the Hancock corps occupied the left flank of the army during the Battle of Cold Harbor . The division of Barlow during the attack managed to achieve temporary success, but the division of Gibbon did not achieve anything. Hancock’s troops lost 3,000 men, and it was “a fatal blow from which the corps would not recover soon,” according to the chief of staff and Hancock himself. Cold Harbor was a failure in Grant's career, and Hancock himself made some mistakes. Mead hoped to continue the attacks, but Hancock said that if the first one fell through, the next ones would be no better. Grant consulted the corps commanders and also decided to cancel the attacks [74] .

Having got into a strategic dead end under Cold Harbor, Grant decided to transfer the army south of the River James and attack Petersburg . On the morning of June 13, the Warren Corps withdrew from the position and crossed the Chikahomini River, followed by the Hancock Corps, which left at 17:30 to the James River at Wilcox Landing. On the morning of June 14, the corps began the crossing, which lasted until the night and ended only at 5 am on June 15. The order required Hancock to wait for transports with provisions, and then go to the mouth of the Harrisons Creek. Waiting for carts delayed him until 10 am, and then it turned out that there was no place in the indicated place of the river. In the evening, Grant's order came, demanding to go to Petersburg quickly and join the Smith corps storming the city. Hancock hurried to Petersburg, but did not have time to start the attack (19:00). Because of this delay, the federal army missed a good opportunity to seize Petersburg [75] .

General Smith immediately lashed out at Grant, Mead, and at the same time Hancock, arguing that only the slowness of the 2nd Corps did not allow Petersburgers to take. The allegations hit the press, and Hancock requested an investigation from Meade. Mead told Grant that, in his opinion, Hancock’s guilt was not there, and Grant replied that Hancock’s reputation was so high that there was no need for an investigation. On June 27, another article appeared in the newspapers accusing Hancock, but at the initiative of Mead, the correspondent was ordered to be arrested for spreading false information. General Smith apologized to Hancock, but Grant did not forgive him for public criticism of a senior officer, and Smith, partly for this reason, was later removed from corps command [76] .

June 15 and the morning of June 16, Hancock, as a senior officer, commanded all the army units at Petersburg, and on the afternoon of June 16, Mead arrived and took command. He immediately ordered to resume the assault, but this attack, which took place in the evening, was repelled. The corps was so exhausted by the battles and suffered such losses in the officer corps, that its fighting capacity was low. Hancock himself was not feeling well and on June 17, temporarily, for 10 days, handed over the corps to General Byrney [77] .

Expeditions to Deep Bottom

In late July, the federal military developed a plan for undermining part of the enemy's trenches, followed by an attack on the IX Burnside Corps - this battle later became known as the Fight at the Funnel . In order to draw off some of the forces from the attack site, Grant conceived a diversion: the two cavalry divisions were to destroy the Virginia Central Railway, and the Hancock Corps had to cross the James River, take up the position at Chaffins Bluff and cover the cavalry maneuver. On July 26, at 4:00 pm, the II Corps left the camp, crossed the Appomattox River, and early in the morning of July 27, began crossing the James River at Deep Bot. For 4 hours the corps managed to cross the river. Immediately behind it, the position of the enemy was discovered, which was taken by the forces of the Miles and Trobriand brigades, and four 20-pound Parrot cannons were captured. This battle went down in history as the . Stepping on, Hancock reached the fortified line of the enemy at the turn of the Bailey Creek. Hanok did not dare to storm the fortifications in the forehead and began to search for ways around. The next day, the Southerners transferred additional forces to Deep-Bot, and Hancock went on the defensive. Grant and Mead arrived at the position and decided that the Hancock offensive pulled away from Peterburg significant forces, so it is better for him to stay here. On the night of June 29, the corps went back and managed to see an explosion of gunpowder, from which the Fight began at the crater [78] .

General Gibbon wrote that after the battle, Hancock made a few comments to him, which he regarded as unfair. Gibbon remarked that Hancock’s attitude toward him had changed and had never been as warm as before. He believed that this was a result of overwork and complications from the Gettysberg wound. Historian David Jordan believes that some of Gibbon’s misunderstandings during the Battle of the Wilderness could affect the Hancock attitude [79] .

The expedition to Deep-Bottom really pulled off significant enemy forces from the front of the Burnside corps, but the attack on July 30 (the battle at the Funnel) ended in failure with heavy losses. On July 31, General Mead ordered an official investigation and handed over to Hancock the position of the commission of inquiry unpleasant for him. After examining all the orders related to the attack on July 30, Hancock called all the officers mentioned in the orders and interrogated them. The process began on August 6 at the headquarters of Hancock and lasted until September 9. As a result, the reasons for the failure were identified and five guilty officers were identified: Ambrose Burnside , , Edward Ferrero, Colonel Bliss and Orlando Wilcox . Following the investigation, Burnside was removed from corps command [80] .

The investigation was in full swing when Grant ordered Hancock to go to Deep Bott again on August 12. The offensive route was the same, but the goals were different: Grant learned that Lee had weakened his front, and hoped to break through. On August 13, the corps was loaded onto transports, and the next day at 4:00 pm the 1st and 2nd divisions under the general command of Francis Barlow attacked the enemy at Fassels Mill. Northerners fought reluctantly: the Irish brigade was unable to execute Barlow’s orders, and the former Brooks brigade was so demoralized that they did not even risk sending it to battle. Both Hancock and Barlow were disappointed. They decided that the problem was a large number of recruits and a lack of experienced officers. The shootings continued for a few more days, until Grant found out that the information about the weakening of the front was false and there was no sense to keep Hancock in Deep Bottom. On August 19 and 20, the corps was brought back to the trenches near Petersburg. Earlier, on August 17, Hancock learned that he was given the rank of brigadier general of the regular army [81] .

Battle at Rims Station

As soon as Hancock and his corps returned from Deep Bott, Grant immediately gave him another assignment. Shortly before that, during the Glob-Tavern battle, the Warren Corps captured a section of the Weldon Railway and destroyed part of the canvas, and now Grant wanted Hancock to dismantle the canvas further south. On August 22, the division of Barlow proceeded to dismantling the canvas and on August 23 she dismantled the station to Rims Station. In the evening, the division occupied the fortifications built here in June by units of the VI Corps. The next day, the Gibbon division approached, and in the evening, Mead informed Hancock that large enemy forces were moving in his direction. On the morning of August 25, noticing the approach of the southerners, Hancock recalled two divisions to fortified positions at Rims Station. He had 6,000 men, mostly recruits, and the fortifications were not put in order. Trenches had the form of the letter "P"; their central section, about 700 meters long, was turned to the west, right to the north and left to the south. The central section was a little to the west of the railway embankment, which prevented ammunition from being brought to the batteries and reinforcements being thrown. Hancock didn’t like this position, but he didn’t do anything to correct it [82] .

In the afternoon, the Southerners under the command of E.P. Hill (4 brigades) stormed the defense area of the Barlow division (which Miles commanded that day) twice, but were beaten off. Hancock requested that Mott's division be handed over to him, but Mead suggested that he retreat. Hancock refused, hoping to hold the position. At 3:00 pm, Henry Heth joined the Hill with four brigades and took over command, due to Hill’s ill health. Around 5:00 pm, the Southerners began a heavy bombardment, and then rushed to the storming of the northern corner of the position and captured it. Three batteries, which were facing west, could not retreat and were captured by the enemy [83] [84] .

The loss of batteries was described a few days later in the newspaper The New York Times :

... our lines were broken near the center, and the gap quickly widened, until almost the entire line was thrown back, leaving trenches and artillery in the hands of the enemy, from the left flank of the 1st division to positions far to the right of the center. It is said that the 7th New York Infantry Regiment was the first to retreat.

The batteries that were thrown were the battery In 1st Rhode Island , Leith. PERRIN; battery cap SLIPERA, 12th Massachusetts, and McNite Battery, 12th New York Independent. All their horses died at the beginning of the battle, and our people retreated so quickly that there was no way to get the guns out.

Original Text (Eng.)It was not until the first line of the first division was taken. a lot of the center. Seventh New York Infantry Batteries B, First Rhode Island, Lieut. PERRINE; Capt. SLEEPER's battery, the Twelfth Massachusetts, and MCKNIGHT's Battery, the Twelfth New-York Independent. It has been a lot of trouble to get rid of the guns.- [85]

The regiments of both divisions, without strong resistance, abandoned the position, and many surrendered. Miles gathered 200 people of his former 61st New York Infantry Regiment and repulsed some of the positions, and Hancock managed to transfer some reinforcements to him and, partly, to save the situation. When it got dark, Hancock invited his divisional commanders to repel fortifications. Miles and Gregg agreed, but Gibbon said that his division could not cope with it. Hancock was forced to retreat. Colonel Morgan from the headquarters of Hancock wrote that the general for the first time in his life experienced the bitterness of defeat. "The second building, once a great fighting machine, was now only a shadow of itself," wrote David Jordan, "and Hancock realized this at Reims Station." Hancock lost about 600 people killed and wounded, and southerners about 700, but Hancock also lost 2,000 prisoners, 9 guns and 12 flags. Immediately after the battle, Hancock's correspondence with Gibbon followed, in which the corps commander so sharply assessed Gibbon's actions that he requested resignation. Hancock twice talked with Gibbon and even admitted that he was “not in himself” when he condemned him, but Gibbon insisted on resigning [86] [87] .

September elapsed for the Hancock corps without event, and in late October he was instructed to go to the flank of the enemy’s positions and, with the support of the V and IX corps, to seize a section of the Southern Railway. On the morning of October 27, Hancock directed the divisions of Egan and Mott to the Boydton Road, but at 13:00 Mead informed him that the IX Corps would not be able to support the offensive, so it is canceled. At the same time, Hancock should remain in his position until the morning, waiting for the Crawford division, which is aimed at helping him. However, Crawford never arrived, but at the end of the day, a detachment of 5,000 Southerners under the command of Henry Heth attacked Hancock’s position, dropped the Pierce brigade and captured several guns. Egan's Division attacked Heth on the flank and beat off the guns. By evening, Hancock began to run out of ammunition, and he decided not to take the risk and take the division. At 10:00, his forces began to retreat, taking advantage of the darkness and heavy rain. didn’t give any results, but it helped the corps to regain the confidence lost after the fight at Rims Station [88] [89] .

The Last Days of War

The battle on Boydton road was the last in the career of Hancock. There was talk that Grant wanted to make him commander-in-chief of the Army of the Potomac. However, Grant instead invited him to lead an independent reserve Veteran Corps, and Hancock agreed. He wrote to Barlow that he did not want to command the Potomac Army and did not want to serve "ignoble people" at all. He did not specify who these people were, although in fact Grant and Mead were his direct superiors. The order on the formation of the new corps and the appointment of Hancock came only on November 28. He immediately began recruiting veterans and managed to recruit 4,400 people. Grant hoped to recruit 20 00 people into the corps and use them in the Shenandoah Valley, but when this did not work out, he appointed Hancock as head of the West Virginia department. He was supposed to launch an attack on the south, but General Lee's army surrendered at Appomattox before the order to attack came. War is over. Towards its end, Hancock became the temporary major general of the volunteer army, the brigadier general of the regular army and one of the most famous military in the country [90] .

On April 9, Stanton authorized Hancock to accept the capitulation of the Southerners under the same conditions on which Lee’s army had capitulated to Appomattox, but to make exceptions for partisan John Mosby . On April 10, Hancock published a circular stating that all Southerners, except John Mosby, could surrender and be conditionally released. On the same day, the news came that Grant required general terms of surrender for everyone, including Mosby. Hancock's headquarters sent Mosby a letter inviting them to discuss the terms of the surrender, but received no reply. On April 13, it was decided to resume the hunt for Mosby, and on April 15, an eight-thousand infantry detachment was supposed to start a Virginia sweep operation from partisans, but just before the operation began, the message about the murder of Lincoln came and the operation was canceled [91] .

Post-war service

Immediately after the war, the assassination of President Lincoln and the assassination of Secretary of War Seward occurred. It happened in Washington, which was located on the territory under the jurisdiction of Hancock, so the new president, Andrew Johnson, immediately called Hancock to the capital. With his participation in Washington, order was established, and the conspirators were arrested. He was also charged with organizing the execution of four death sentences on the morning of July 7. One of those sentenced was . Hancock, probably trying to avoid the execution of a woman, waited for a presidential amnesty for a while. His wife later claimed that he had repeatedly requested amnesty from the president. But that never happened. According to lawyer John Clampitt, Hancock told him: “I have been to hell from fire, shells and shrapnel, but I'd rather be there ten thousand times again than I gave the order today to execute this unfortunate woman. But I am a military man, called to obey, and I obey. ” On the same day, the condemned were executed. Participation in the execution of Mary Suratt then often recalled Hancock during presidential campaigns [92] .

After these events, Hancock lived for some time in Baltimore, and in the meantime, Congress awarded General Grant the rank of full army general, his rank of lieutenant general passed to Sherman , who in turn freed up the position of major general. Grant recommended Hancock to this place, and the title was awarded. In August of the same year, Hancock was sent to the West at the disposal of Sherman, who had long asked for an experienced officer who was able to restore order on the frontier. Hancock took command of the Missouri military department, in which at that time the situation was calm, but potentially explosive. On March 8, Sherman instructed Hancock to take a detachment of 1,400 people and march across the plains, offering the Indians either to accept the battle now, or to go to a peace agreement. On March 25, Hancock arrived at Fort Riley, from where he marched to the forts Harker and Zara, sending forward the 7th Cavalry Regiment, commanded by Andrew Smith and George Custer . From there, a detachment on April 7 came to Fort Larned, where Agent promised to meet with the leaders of the Indians on April 10. The Indians lingered, and only on the evening of April 12, the leaders of High Bison and White Horse arrived at Hancock. Not having obtained from them a clear statement, Hancock went to the nearest Cheyenne village, on the way to which he met a detachment of Indians and the leader of the Roman Nose . The Indians avoided contact, and when Hancock approached the village, he discovered that all its inhabitants had left. Hancock regarded this as a manifestation of hostility and decided to destroy the village, although he hesitated with the adoption of this decision. On April 17, Caster informed him that several whites had been killed nearby by Indians. On the morning of April 19, 250 huts and about 1000 pieces of bison hides were burned by order of Hancock. He then negotiated at Fort Dodge with the Kiowa and Arapaho Indians and returned to Fort Larned. On May 9, Hancock completed the expedition and returned to Fort Leavenworth . He did not achieve any results, only angered the Indians, attacks that have become frequent since that time [93] .

In Louisiana

In the summer of 1867, President Johnson decided to carry out personnel changes — send Sheridan to Missouri, and transfer Hancock to the 5th military district (Louisiana and Texas). The official order was published on August 26, 1867. Hancock was not very pleased with this appointment, but obeyed the order. November 28, he arrived at his office in New Orleans. The government was counting on its democratic views and on the fact that it would follow the conservative policy of Reconstruction , protecting the rights of the white population. On November 29, Hancock issued General Order No. 40, where he announced that in the event of a peaceful development of events, the military administration would gradually recede into the background, giving way to a civilian. The order caused the approval of the white population of the South and the discontent of the radical Republicans , whose power was established in New Orleans by General Butler during the war years and now came to an end under the rule of civil administration. Hancock believed that after the unification of the country and the abolition of slavery, the problems were settled and there was no need to change the social order in the South [94] .

On January 11, Hancock canceled the rules of registration entered by Sheridan to the constitutional council. The Sheridan rules gave Black an advantage and set many restrictions for whites, with the result that in September 1867 of the 127 639 council elections there were 82 907 black people, and of the 98 elected delegates 96 were Republicans. Hancock measures allowed Democrats to regain influence in the state. Hancock also had disagreements with Texas Governor Elisha Pease , who complained that white Texas residents were uncomfortable with the government, to which Hancock responded that in his opinion dissatisfaction, if not expressed in violations of the law, is beyond the competence of state structures. Still, disagreements with Grant on some issues forced Hancock to ask for resignation, and on March 16, 1868, he left for Washington. His brief tenure as head of the district seriously changed his life, turning him into a major political figure of a democratic orientation [95] .

Presidential Election 1868