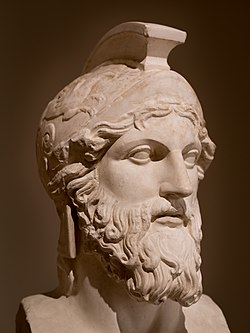

Milthiad ( Greek: Μιλτιάδης ; c. 550 - 489 BC ) - Athenian statesman, commander of the period of the Greco-Persian wars ( 500 - 449 BC), tyrant of Chersonesos of Thrace ( around 520 [1] —493 BC), the son of Cimon the Elder (who was the half-brother of Miltiad the Elder ), the father of Cimon the Younger.

| Miltiad | |

|---|---|

| Greek Μιλτιάδης | |

| |

| Date of Birth | about 550 BC e. |

| Place of Birth | Athens |

| Date of death | 489 BC e. |

| Place of death | Athens |

| Citizenship | Athens , Persia |

| Occupation | Athenian strategist |

| Father | Cimon the Elder |

| Spouse | Hegesipila, daughter of the Thracian king Olor |

| Children | sons Metiochus and Cimon |

Miltiad came from an ancient aristocratic family. In 524 BC e. was elected archon - eponym in Athens, and then (from 520 BC ) ruled as a tyrant the Thracian Chersonesos as heir to Miltiad the Elder . In 513 BC e. he was forced to become a vassal of the Persian king Darius Gistasp and accompanied him on a campaign against the Scythians and was left with the other Greeks to guard the bridge built by the Persians on the Danube River . During the Ionian uprising, Miltiad had to leave Khersones and sail to Athens. In Athens, he was accused of being a tyrant in Thrace , but was acquitted.

After the trial, Miltiad becomes one of the most influential politicians in Athens [2] . In 490 BC e. Miltiad was elected to the college of strategists. In the same year, Darius sent an expedition to the Aegean Sea, the purpose of which was to conquer Athens. Familiar with Persian tactics, Miltiad persuaded the military council to give battle to the Persians in an open field; having, thanks to the voluntary yielding of the remaining strategists, to his own hands the chief command over the army, Miltiad took full advantage of the location and, with a strong pressure, stunned the Persians, defeated them at the Marathon .

The following year, Miltiad proposed starting a campaign on the Cyclades. Under his leadership, the Athenians besieged the island of Paros , but the blockade ended in failure; Miltiad himself was wounded and returned to Athens, having not achieved any results. He was accused of “deceiving the people” and sentenced to a fine of 50 talents and soon died of wounds received during the siege of Paros.

Browse Sources

The main source telling about the life of Miltiad is the "History" of Herodotus . Herodotus described the origin of Miltiad, the deeds of his closest ancestors and relatives, the first Athenian and Kherson periods of his life, and described in detail the last stage of his career - the time of Miltiad's greatest glory. At the same time, Herodotus did not have a single and coherent narrative about Miltiade. Rather, it is a chain of individual excursions that are characteristic of the work of Herodotus [3] .

Most of the information about Miltiade in later sources directly or indirectly goes back to Herodotus. However, in these sources some new details of his biography are mentioned. However, their reliability cannot be precisely determined. The image of Miltiad, along with the formation of a tradition about him, was increasingly subjected to mythologization. His image became the subject of a propaganda struggle, the banner of any trends, which did not contribute to the formation of an objective attitude towards him [4] .

Roman biographer of the 1st century BC e. Cornelius Nepot wrote a biography of Miltiad, which opens his collection "On the great foreign commanders." This biography is uninformative and not entirely reliable. It is a mixture of information from the “History” of Herodotus and the author’s speculation. There is a lot of confusion and inconsistencies in it. So, Nepot mixes two Miltiads - the Elder and the Younger, combining them into one person. It is not known whether the biography of Miltiada Plutarch wrote. Of the 71 biographies he wrote, 50 survived. In any case, even if Plutarch wrote his biography, it did not survive [5] .

The first Athenian period of life. Origin

Miltiad, son of Cimon, from the deme of Laciades was born in Athens in the middle of the VI century. BC e. The exact date of his birth is unknown. Most often, the date of his birth is conventionally called 550 BC. e. Although most likely, he was born no later than 554 BC. e., since in 524/523 BC. e. held the post of archon - eponym , which could be held by persons who have reached the age of thirty [6] .

Miltiad came from a noble aristocratic family of the Philids . Representatives of this kind erected their origin to the son of Zeus Eak . Eak had a grandson, Ajax , king of Salamis , and the son or grandson of the latter was Philae , who moved to Attica and became the ancestor of Philaids [7] [8] [9] . Even in the archaic era, representatives of this genus were famous political figures of Athens [10] .

The two largest representatives of the Philaids were Uncle and father Miltiada. Miltiad's uncle was Miltiad, the son of Kipsel , who is usually called Miltiad the Elder. He was one of the most influential political leaders of Athens in the middle of the VI century. BC e. In establishing the tyranny of the Pisistratides, he was not injured, but was dissatisfied with the situation [7] . Therefore, taking advantage of the offer of the Dolon tribe to become their leader, he sailed to Chersonesus of Thrace around 560 BC. e. Miltiad became the first tyrant of the Thracian Chersonesos from the Filaid clan. At the same time, he remained at the same time an Athenian citizen and maintained contact with Athens. Perhaps he became a tyrant with the consent of the Pisistratides, who wanted to establish Athenian control over the North Aegeid . Ownership of the peninsula provided control over the strategically important Hellespont Strait [11] .

Milthiad the Elder's half-brother was Cimon, son of Stesagoras. He was not very active in politics, but succeeded in racing on chariots, becoming a three-time Olympic winner. The peisistratids, however, were afraid of his influence, and for some time Cimon went into exile, and then returned. He was killed by order of Hippus and Hipparchus in 524 BC. e. [12]

Cimon had two sons, Stesagor and Miltiad. Stesagor became the heir to his childless uncle Miltiad the Elder, and after his death around 525 BC. e. became the tyrant of Chersonesus of Thrace [12] . He ruled briefly and died in the war with Lampsacus around 520 BC. e. [one]

In childhood and youth, Miltiad, apparently, was in exile with his father and returned to Athens at the end of the reign of Pisistratus . In 524 BC e. the tyrants Hippias and Hipparchus ordered the assassination of Cimon, but they favorably favored his son. In the same year Miltiad was elected an eponymous archon [13] .

Tyranny on Chersonesos

Around 520 BC e. the tyrant of Chersonesus of Thracian Stesagoras died, and the Peisistratides, not wanting to lose control of this area, sent Miltiada there. He managed to seize power there, eliminating the dissatisfied, and soon married Hegesipilus, daughter of the Thracian king Olor , which ensured him the friendly attitude of Thrace [14] .

In 513 BC e. a large Persian army led by Tsar Darius I crossed from Asia to Europe. Moving against the Scythians , the Persians conquered the Greek cities in Thrace. Most of the rulers of these cities, realizing the impossibility of resistance, voluntarily recognized dependence on the Persians and joined the campaign against the Scythians [15] . Among them was Miltiad, who took this step voluntarily and deliberately. He could not run back to Athens, as political struggle broke out there, and the tyrant Hippias could eliminate him [16] .

Having built a bridge over the Danube and transferred his army along it, Darius I delved into the North Pontic steppes, and the Greek tyrants accompanying him left the crossing to guard. Herodotus and Nepot wrote that Miltiad accepted the Scythian proposal to destroy the bridge, leaving Darius in Scythia, and the Greek tyrants suggested returning to their cities [17] [18] . This was opposed by the Milesian tyrant Hystia , who indicated that they remained tyrants in their cities only thanks to Darius, and if the Persians were defeated, the demos would seize power in their cities, overthrowing them. The remaining tyrants agreed with Gistiyeh and waited for Darius. This story is most likely false and was invented by Herodotus to show Miltiada in a better light. In favor of this is the fact that Darius did not punish Miltiad after his return from the campaign [19] .

The Scythians in response to the campaign of Darius invaded the territory subject to the Persian Empire and reached Chersonesos. Miltiad was forced to flee into exile [20] . After spending several years in exile, he returned to Chersonesos and regained his power. The date of these events is not exactly known due to the complexity in the presentation of Herodotus [21] . Perhaps during exile he captured Lemnos . Herodotus mentioned this event, but did not write when it happened [22] . Miltiad expelled the Pelasgians who had previously inhabited it from Lemnos and founded the settlement of the Athenians on the island [22] [23] [24] . At the same time, it is specially emphasized that he arrived at Lemnos from Chersonesos of Thrace. Perhaps Lemnos had already been conquered earlier, and Herodotus confused Miltiad the Younger with Miltiad the Elder. Most likely, it was on Lemnos that Miltiad spent the years of exile [25] .

In 499 BC e. the Ionian uprising began. The Ionian Greeks revolted against Persian rule. The Athenians and Eretrians sent 25 ships to their aid. Although the Athenians later recalled their ships, Darius decided to take revenge on them. The Persians were able to seize the initiative and began to crush the rebellion. Nothing is known about Miltiad’s participation in the uprising. Most likely, he waited and did not take active actions. However, he was an Athenian, and Darius therefore had doubts about his loyalty [26] . In 493 BC e. the Persian fleet advanced along the west coast of Asia Minor to Chersonesos, capturing the rebellious cities along the way. Miltiad was forced to flee.

He collected 5 triremes, loaded his treasures on them and sailed from Cardia . Going around Chersonese, he met with Phoenician ships. Four ships managed to slip, and one fell into the hands of the Persians. On this ship was Milthiad's eldest son, Metioch. Darius graciously accepted Metiochus and even granted him an estate. Miltiad arrived at Imbros , and from there sailed to Athens [27] .

Second Athenian Period

Return

Miltiad, after almost thirty years of absence, returned to his hometown. Athens has changed a lot during his absence: Hippias was expelled and tyranny was eliminated, Klisfen reforms were carried out and democracy was established. Demos was gaining strength in the polis. Now, not only the aristocracy ruled the city, aristocrats had to reckon with the opinion of the whole people. In addition, Miltiad immediately had enemies who saw him as a political rival [28] .

Immediately after returning, he was charged with tyranny on Chersonesos. Ever since the archaic era, Athens had a law against tyranny [29] , which, apparently, became the legal basis for the prosecution of Miltiada [30] . Who prosecuted him is unknown. It could be Themistocles , who at that time held the post of archon-eponym, or Xanthippus , who led the political group Alkmeonides [31] . Miltiad justified himself in court, saying that his rule in Chersonesos was aimed at the good of Athens.

After the trial, Miltiad becomes one of the most influential politicians in Athens [2] . He was elected a strategist [30] and subsequently re-elected to this position. The reasons for such a rapid rise were his origin, the fact that he brought great wealth from Chersonesos and had experience in government activities. At the same time, he was a tyrant, which was negatively perceived by the Athenians, and did not show much sympathy for democracy [32] .

Under the influence of external causes in Athens, a crisis of the political line of the Alkmeonids was brewing, the components of which were enmity with Sparta and conciliatory relations with Persia. These two foreign policy issues were central in Athens of that time: relations with Sparta and relations with Persia. Different political groups had different positions on this issue: the group of Hipparchus, the son of Kharm, was Prospartan and Propersidian, the Alkmeonid group led by Xanthippus was anti-Spartan and Propersidian, the group of Themistocles was anti-Spartan and anti-Persian. Miltiad took a position that none of the groups took: his views were Pro-Partan and Anti-Persian [33] .

The positions of Miltiad and Themistocles coincided in their anti-Persian orientation. However, the methods of warfare were very different. Themistocles relied on the use of naval forces. Miltiad, on the contrary, believed that the outcome of the war would be decided in land battles, and therefore the fighting ability of the Hoplite phalanx should be strengthened [34] .

In 491 BC e. Persian ambassadors arrived in Athens demanding "land and water." They were killed at the initiative of Miltiada [35] . This act of demonstrative cruelty made war with the Persians inevitable. In addition, he was contrary to generally accepted standards for the integrity of ambassadors [36] . However, in Sparta, the ambassadors were killed: the Spartans threw them into the well, offering to take land and water from there [37] .

Battle of the Marathon

In 490 BC e. the Persian king Darius I sent a punitive expedition to Western Aegis under the command of Datis and Artafern [38] . Departing from Cilicia , the Persians (their number is about 20 thousand people) kept their course along the central part of the Aegean Sea, from island to island. Along the way, they captured several strategically important centers: Naxos , Delos , etc. After a 6-day siege , Eretria was taken [39] [40] . From Euboea, the Persians crossed the narrow strait of Euripus to Attica and camped at the Marathon [41] . The marathon plain was convenient for the actions of a strong Persian cavalry [42] .

The near danger caused confusion in Athens. Among the Athenians there were supporters of resistance, and his opponents. Miltiad was able to organize the mobilization of all forces for armed resistance, having led a psephism through the popular assembly [43] . Psefisma Miltiada provided for the recruitment of all combat-ready male citizens into the ranks of the militia militia, as well as the release of a certain number of slaves to replenish the army [44] . Despite all efforts, it was possible to collect about 9 thousand hoplites [44] [45] . A messenger was sent to Sparta asking for help, but the Spartans hesitated, citing religious precepts. Residents of the Boeotian city of Plathea sent all their militia of one thousand people to help the Athenians [46] [47] .

“It is in your hands, Callimachus, to make the Athenians slaves or to free them [...] After all, since Athens has existed, they have never been in such terrible danger as they are now. [...] We - ten strategists - disagreed: some advise giving battle, while others do not. If now we do not decide on a battle, then I fear that great strife will come over and so shock the souls of the Athenians that they will submit to the Medes. If we fight the enemy before anyone has a vile design, then we will overcome, because there is divine justice. All this is now in your power and depends on you. Join my advice, and your hometown will be free and become the most powerful city in Greece. And if you take the side of the opponents of the battle, then, of course, we died ” [48] .

Athenian-plateau troops marched to the marathon. It was unprofitable to wait for Persian troops in the city: the walls were not too fortified, and traitors could be found in the city [49] . The Athenians camped at the Marathon near the Persians [12] [50] [51] . The nominal commander was archon polemarch Callimachus, and in his submission he had ten strategists who alternately commanded the army, including Miltiad. Of these, he was the most talented, most experienced and most energetic. Among strategists there was debate about further actions against the Persians [48] . Miltiad called for an immediate general battle. Others called for a wait-and-see tactic, fearing the superiority of the Persian forces. The opinions of strategists were divided: five supported the battle, including Miltiad and Aristide [51] , five opposed. Miltiad convinced Callimachus of the need for an immediate battle. [48] Then all the strategists, following Aristide, gave up their days to command Miltiad [51] [52] . Мильтиад разработал план сражения и претворил его в жизнь.

Афинское войско заняло позицию на хребте Пентеликон, труднодоступном для нападения, и таким образом перекрыло дорогу от Марафона к Афинам. Персы, имевшие численное превосходство, не стали ни нападать на греков, ни пытаться их обойти. Датис решил посадить воинов обратно на корабли и высадить армию в Фалере, рядом с Афинами. После того, как большая часть персидской конницы и часть персидской пехоты были посажены на корабли, Мильтиад решил атаковать персов. Учитывая двукратное превосходство сил персов, Мильтиад во избежание окружения сильно растянул афинскую фалангу по фронту, укрепив фланги за счёт центра и сконцентрировав на них основные силы, а затем с помощью внезапной стремительной атаки использовал преимущество сомкнутого строя греческих гоплитов над рассыпным строем легковооружённых персов, поддерживаемых конницей и лучниками [53] .

12 сентября 490 года до н. e. афиняне и платейцы неожиданно для персов атаковали их. Сомкнутый строй греческих гоплитов имел преимущество над рассыпным строем легковооружённых персов, поддерживаемых конницей и лучниками, поэтому греки поначалу теснили персов. Персидские всадники, ошеломлённые натиском греков, так и не смогли принять существенного участия в сражении [53] . Центр греческого войска несколько отступил под давлением превосходящих персидских сил, но это было предусмотрено Мильтиадом. Он отдал приказ флангам развернуться и нанести удар в тыл прорвавшимся в центре персам. Это привело к окружению и истреблению значительной части сил противника. Оставшиеся в живых персы отступили к кораблям и немедленно вышли в море.

Отчалив от Марафона, персидские суда двинулись в обход Аттики , чтобы попытаться захватить Афины: ведь город оставался беззащитным, пока всё полисное ополчение находилось на поле боя, в 42 километрах от него. Однако Мильтиад тут же, без передышки после битвы, совершил со всем войском (оставив на месте лишь небольшой отряд во главе с Аристидом для охраны пленных и добычи) форсированный марш в полном вооружении к Афинам и оказался в них раньше, чем персидский флот. Увидев, что город хорошо охраняется, деморализованные персы, так ничего и не добившись, отправились обратно [54] . Карательная экспедиция персов окончилась провалом.

Афиняне и платейцы под командованием Мильтиада одержали блестящую победу. В бою погибло 192 грека и 6400 персов [55] . Победа подняла боевой дух афинян и впоследствии осталась в их памяти как символ величия Афин [56] . Очень большую роль в победе сыграл Мильтиад. Но сограждане не были склонны должным образом признать его заслуги. Когда Мильтиад просил награждения масличным венком, ему отказали, намекнув, что победа одержана всеми воинами, а не только им одним [57] . Граждане были убеждены в том, что победа при Марафоне — их общее дело, а не заслуга одного Мильтиада [58] . Аристотель отметил, что именно после Марафонской битвы демос «стал чувствовать уверенность в себе» [59] . Честолюбивый Фемистокл часто повторял: «Лавры Мильтиада не дают мне спать» [60] . Данная фраза впоследствии стала крылатой [61] .

Возможно, Мильтиад планировал стать тираном, опираясь на свой авторитет и недавно одержанную победу, но его позиции, как ни странно, после этого не стали более крепки [58] .

Экспедиция на Парос

около 550 до н. e. — рождение Мильтиада

524 до н. e. — убийство Кимона, отца Мильтиада

524/523 до н. e. — архонтство Мильтиада

520 до н. e. — начало тирании Мильтиада на Херсонесе Фракийском

513 до н. e. — Мильтиад становится вассалом персидского царя Дария I. Участие в Скифском походе. Скифы изгоняют Мильтиада из Херсонеса

около 510 до н. e. — Возвращение Мильтиада на Херсонес

493 до н. e. — Мильтиад вынужден бежать из Херсонеса. Возвращение в Афины. Суд над Мильтиадом. Избрание его стратегом

491 до н. e. — по инициативе Мильтиада убиты персидские послы

490 до н. e. — командование афинско-платейской армией в Марафонской битве

489 до н. e. — неудачаная экспедиция на Парос. Осуждение Мильтиада. Он приговорён к уплате большого денежного штрафа. Смерть Мильтиада

In 489 BC e. he proposed a sea expedition to the Cyclades islands under the pretext of punishment for helping the Persians [62] . The real goals of the campaign were the robbery of the islanders and the enrichment at their expense. Presumably, Miltiad also pursued personal goals, planning to capture an island and make it his possession [63] .

He swam to Paros . Arriving there, Miltiad besieged their city and demanded 100 talents. The sailors refused and began to prepare intensely for the defense. Herodotus reports the version of the Parosians that he injured his hip or knee, trying to sacrilegiously penetrate the Parosan sanctuary of Demeter [64] . In fact, Miltiad received a serious wound during the siege, which at first seemed insignificant [63] . He lifted the siege and sailed to Athens, only ravaging the surroundings of Paros in 26 days of the siege [65] .

At home, Miltiad's rivals brought him to trial, Xantippus was the prosecutor [66] . He accused Miltiad of treason, and the death penalty was to be punished}. Miltiad himself was present at the National Assembly, but he began to have inflammation in his thigh, and he lay on the bed, and his supporters spoke out in his defense. They succeeded in mitigating the indictment. He was found guilty of “deceiving the people” and sentenced to pay a large fine (50 talents) [66] . Miltiad could not immediately pay the fine and was credited to state debtors. Debtors were forbidden to participate in political activities. Miltiad soon died from a wound received during the siege of Paros. Some ancient authors, in particular Herodotus, wrote that Miltiad died in prison, but this is not true: state debtors began to be imprisoned after 400 BC. e. [67] Miltiad was buried on the Marathon Plain. [68]

Personality

Personal life

Miltiada's first wife was a certain Athenian woman whose name is unknown. From their marriage, the son Metioch was born. Having become the tyrant of Chersonesus, Miltiad married Gegesipile, daughter of the Thracian king Olor .

Metiochus was captured by the Phoenicians when Miltiad fled to Athens. The Phoenicians took him to King Darius in Susa . Darius received him favorably and “granted him a house, an estate, and a Persian wife” [27] . In their marriage, children were born who were already considered Persians. Perhaps the Persian king decided to use Metiochus as a hostage. If so, then Darius did not achieve his goal. In the future, Miltiad acted as if his son had not been with the Persians at all [28] .

From the marriage of Miltiad with Gegesipila, Cimon was born, who later became one of the most influential politicians of Athens [69] . Cimon’s sister was Elpinica , one of the most notorious personalities of his era. She was repeatedly attacked, she was accused of incest with her brother, in the vicinity of the artist Polygnot , and that in general she was dishonorable. The reason for this hostile attitude was her active participation in politics, since in those days the participation of women in such matters was considered reprehensible. Elpinica survived Cimona and died after 439 BC. e. [70]

Political Opinions

The political views of Miltiad are not completely clear. He grew up during the tyranny of the Pisistratides, when the position of the aristocracy was very strong. He came from an ancient aristocratic family, whose representatives did not show special sympathy for democracy. Returning to Athens, Miltiad found a completely different setting, very different from the situation at the beginning of his career. New conditions were unusual for him. Now, not a narrow stratum of aristocracy, but the whole people of Athens participated in politics. It was difficult for Miltiad to put up with this, but he had to adapt to the new situation [71] .

Nevertheless, Miltiad almost immediately after his return became almost the leader of the policy. His Prospartan and anti-Persian views were most acceptable in the face of the growing Persian threat [34] . After the Battle of Marathon, however, his position was shaken. He had contradictions with the growing demos, and he was perceived as too influential politician [63] , who on occasion could become a tyrant. Therefore, immediately after the failure of the Paros expedition, Miltiad became the object of cruelty and revenge of the Athenians [72] . Having formed as a person in the conditions of an archaic aristocratic ethnos, he could not find his place in the new conditions of democratic Athens [73] .

Memory

Some time after the death of Miltiad, his attitude towards him became more and more positive [69] . His son Cimon made a great contribution to the posthumous rehabilitation of his father. During the reconstruction of the Agora in Athens (the 60s of the 5th century BC), initiated at the initiative of Cimon, a painted standing was erected. The painter Polygnot depicted in one of the paintings the Battle of Marathon. Miltiad stood out in the foreground, encouraging the soldier and signaling the battle [74] [75] .

The sculptor Phidias also contributed to the glorification of Miltiada. In those same years, he created a sculptural group in Delphi , which, according to his plan, was to glorify Athens and their victory at the Marathon [76] . In this group there are sculptures of gods and heroes, and Miltiad is the only historical person in it. Such exaltation is characteristic and significant [77] .

In later sources, Miltiad is given very positive assessments. He became a textbook example of unattainable valor and patriotism [73] . Pausanias even called him "the first benefactor of the entire Hellenic people" [78] .

Miltiad is a character in several historical novels, including Darius by Victor Porotnikov .

During excavations in Olympia , the Miltiada bronze helmet was found, which is now in the local archaeological museum [79] .

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 Surikov, 2005 , p. 300.

- ↑ 1 2 Aristotle. Athenian polity. 28.2

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 291.

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 291-292.

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 292.

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 293-294.

- ↑ 1 2 Herodotus. VI. 35

- ↑ Plutarch. Solon. ten

- ↑ Pausanias. I. 35.2

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 295.

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 297-299.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Herodotus. VI. 103

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 300-301.

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 39

- ↑ Herodotus. IV. 138

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 302-303.

- ↑ Herodotus. IV. 137

- ↑ Cornelius Nepot. Miltiad. 3

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 304.

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 40

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 305.

- ↑ 1 2 Herodotus. VI. 140

- ↑ Diodorus. X. 19. 6

- ↑ Cornelius Nepot. Miltiad. 2

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 305-306.

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 306.

- ↑ 1 2 Herodotus. VI. 41

- ↑ 1 2 Surikov, 2005 , p. 307.

- ↑ Aristotle. Athenian polity. 16.10

- ↑ 1 2 Herodotus. VI. 104

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 308.

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 308-309.

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 309-310.

- ↑ 1 2 Surikov, 2005 , p. 311.

- ↑ Pausanias. III. 12.7

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 310.

- ↑ Herodotus. VII. 133

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 94

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 98

- ↑ Strabo. X. 448

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 102

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 313.

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 313-314.

- ↑ 1 2 Pausanias. X. 20. 2

- ↑ Cornelius Nepot. Miltiad. five

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 108

- ↑ Demosthenes. LIX. 94

- ↑ 1 2 3 Herodotus. VI. 109

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 315.

- ↑ Cornelius Nepot. Miltiad. four

- ↑ 1 2 3 Plutarch. Aristide. five

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 110

- ↑ 1 2 Surikov, 2005 , p. 317.

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 115-116

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 117

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 318.

- ↑ Plutarch. Kimon. eight

- ↑ 1 2 Surikov, 2005 , p. 319.

- ↑ Aristotle. Athenian polity. 22.3

- ↑ Plutarch. Themistocles. 3

- ↑ Serov Vadim. Laurels of Miltiada prevent me from sleeping . Encyclopedic Dictionary of winged words and expressions. Date of treatment August 29, 2011. Archived January 24, 2012.

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 122-123

- ↑ 1 2 3 Surikov, 2005 , p. 320.

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 133-134

- ↑ Herodotus. VI. 135

- ↑ 1 2 Herodotus. VI. 136

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 321-322.

- ↑ Pausanias. I. 32. 4

- ↑ 1 2 Surikov, 2005 , p. 322.

- ↑ Surikov, 2008 , p. 204-205.

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 307-309.

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 321.

- ↑ 1 2 Surikov, 2005 , p. 324.

- ↑ Cornelius Nepot. Miltiad. 6

- ↑ Pausanias. I. 15. 3

- ↑ Pausanias. X. 10. 1-2

- ↑ Surikov, 2005 , p. 323.

- ↑ Pausanias. Viii. 52.1

- ↑ Helmet of Miltiad (inaccessible link) . Date of treatment April 2, 2012. Archived April 2, 2012.

Literature

Sources

- Herodotus . Story

- Plutarch . Comparative biographies . Aristide, Themistocles

- Aristotle Athenian polity

- Pausanias . Description of Greece

Research

- Curtius E. History of Ancient Greece. - Mn. : Harvest, 2002 .-- T. 2 .-- 416 p. - 3000 copies. - ISBN 985-13-1119-7 .

- Sergeev V.S. Chapter IX. Greco-Persian Wars // History of Ancient Greece. - M .: AST, 2008 .-- S. 319-322. - 926 p. - 3000 copies. - ISBN 978-5-17-052484-6 .

- Surikov I.E. Chapter V. Miltiad, or the condemned winner // Ancient Greece: politicians in the context of the era: archaic and early classics . - M .: Nauka, 2005 .-- S. 212—271. - 351 p. - ISBN 5-02-010347-0 . Archived January 30, 2016 on the Wayback Machine

- Surikov I.E. Chapter IV. Cimon: an aristocrat, but not an oligarch // Ancient Greece: politics in the context of the era . - M. :: Nauka, 2008 .-- 383 p. - ISBN 978-5-02-036984-9 . Archived May 21, 2012 on Wayback Machine

- Holland T. Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. - New York: Doubleday, 2005 .-- ISBN 0385513119 .